Watts, Williams, The Bach Choir, Philharmonia, Hill, RFH review - Vaughan Williams, from decadence to metaphysics | reviews, news & interviews

Watts, Williams, The Bach Choir, Philharmonia, Hill, RFH review - Vaughan Williams, from decadence to metaphysics

Watts, Williams, The Bach Choir, Philharmonia, Hill, RFH review - Vaughan Williams, from decadence to metaphysics

VW anniversary celebrated with a popular overture, an early rarity and a masterpiece

David Hill, long-term driving force of the Bach Choir which Vaughan Williams sang in for 18 years before becoming its music director in 1921, claims VW as “a quintessentially English composer”.

That was rather less the case in Thursday night's choice of works gilded by the Philharmonia at the Royal Festival Hall. The Overture to The Wasps is influenced by French and Russian examples, the early Swinburne setting The Garden of Proserpine offers a kind of late-romantic lingua franca, and, sea shanties apart, A Sea Symphony unfurls what its chosen genius Walt Whitman calls “a pennant universal”.

Fortunately this was a performance which engaged with the poetic meanings at the work’s different levels: Whitman’s bracing sea pictures, remembrance of lives lost, man and nature, the metaphysical sea-journey of the soul. It connected the masterpiece to the two more modest offerings of the first half, too: the second robust melody thrown up by the buzzing in the famous overture, part of a less familiar set of incidental music, to a 1909 Cambridge University production of Aristophanes’ The Wasps, is heard, transfigured in reverie as “O vast Rondure, swimming in space” at the start of A Sea Symphony’s finale, “The Explorers”.

As for The Garden of Proserpine, composed between 1897 and 1899 while Vaughan Williams was working on a doctoral thesis, the very end justifies the means. Which up to that point are a striking theme prettily clad and a fairly conventional interchange of fury and stasis. Swinburne’s view of Proserpine-Persephone keeps her firmly in the underworld, tending poppies for the forgetfulness of dead men, and doesn’t return her to mother Demeter’s realm on earth. The decadent obsession with “sleep eternal in an eternal night” is the final note of the poem, but VW rejects morbidity. The soprano’s two penultimate stanzas could be detached as a song – they embrace Swinburne’s best lines – while the last has the chorus mostly on a unison monotone, prophetic of things to come in A Sea Symphony, a harmonic resolution and then a slow fade of the kind the composer wrought so magically in many of his finest works to come. Though the creator never tried to get the work performed, all this justifies its resuscitation.

As for The Garden of Proserpine, composed between 1897 and 1899 while Vaughan Williams was working on a doctoral thesis, the very end justifies the means. Which up to that point are a striking theme prettily clad and a fairly conventional interchange of fury and stasis. Swinburne’s view of Proserpine-Persephone keeps her firmly in the underworld, tending poppies for the forgetfulness of dead men, and doesn’t return her to mother Demeter’s realm on earth. The decadent obsession with “sleep eternal in an eternal night” is the final note of the poem, but VW rejects morbidity. The soprano’s two penultimate stanzas could be detached as a song – they embrace Swinburne’s best lines – while the last has the chorus mostly on a unison monotone, prophetic of things to come in A Sea Symphony, a harmonic resolution and then a slow fade of the kind the composer wrought so magically in many of his finest works to come. Though the creator never tried to get the work performed, all this justifies its resuscitation.

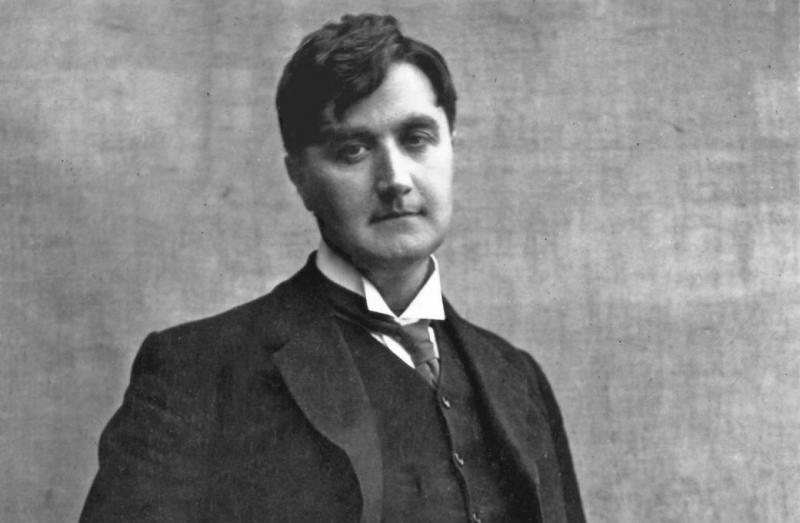

Elizabeth Watts (pictured above by Marco Borggreve) had much to project here, and like her fellow soloist in A Sea Symphony, Roderick Williams, she is always, as they say, “in the zone”. With Whitman’s poetry, such a breath of fresh air still blowing in from the 19th century to the early years of the 20th, both hit the heights and sounded the depths. The “clef of the universes and of the future” is evoked by the onlooker “On the Beach at Night Alone” in the mystical second movement; Williams set the tone poignantly and in the closing stages, where the voice gives up and the orchestra carries the metaphysics onward to the end, Hill got the exquisite Philharmonia to play as softly as possible; even the coughers in the surprisingly full house were stilled. Our baritone again took us inward in the later stages of the finale, after a soaring operatic duet, and the infinite reaches were once again struck.

The big extrovert moments need a big chorus – nearly 200 voices, on this occasion, and so the tingle quotient was high from the very first “Behold, the sea itself” via ther "one flag" manifesto of world unity - more needed now than ever - to the last waves of sound before the final subsiding. In the tricky Scherzo, “The Waves”, we needed more consonants, more open vowels; but no doubt about it, this was a special occasion, as all participants made abundantly clear.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

Anja Mittermüller, Richard Fu, Wigmore Hall review - a glorious hall debut

The Austrian mezzo shines - at the age of 22

Anja Mittermüller, Richard Fu, Wigmore Hall review - a glorious hall debut

The Austrian mezzo shines - at the age of 22

First Person: clarinettist Oliver Pashley on the new horizons of The Hermes Experiment's latest album

Compositions by members of this unusual quartet feature for the first time

First Person: clarinettist Oliver Pashley on the new horizons of The Hermes Experiment's latest album

Compositions by members of this unusual quartet feature for the first time

Gesualdo Passione, Les Arts Florissants, Amala Dior Company, Barbican review - inspired collaboration excavates the music's humanity

At times it was like watching an anarchic religious procession

Gesualdo Passione, Les Arts Florissants, Amala Dior Company, Barbican review - inspired collaboration excavates the music's humanity

At times it was like watching an anarchic religious procession

Classical CDs: Camels, concrete and cabaret

An influential American composer's 90th birthday box, plus British piano concertos and a father-and-son duo

Classical CDs: Camels, concrete and cabaret

An influential American composer's 90th birthday box, plus British piano concertos and a father-and-son duo

Cockerham, Manchester Camerata, Sheen, Martin Harris Centre, Manchester review - re-enacting the dawn of modernism

Two UK premieres added to three miniatures from a seminal event of January 1914

Cockerham, Manchester Camerata, Sheen, Martin Harris Centre, Manchester review - re-enacting the dawn of modernism

Two UK premieres added to three miniatures from a seminal event of January 1914

Kempf, Brno Philharmonic, Davies, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - European tradition meets American jazz

Bouncing Czechs enjoy their Gershwin and Brubeck alongside Janáček and Dvořák

Kempf, Brno Philharmonic, Davies, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - European tradition meets American jazz

Bouncing Czechs enjoy their Gershwin and Brubeck alongside Janáček and Dvořák

Solomon, OAE, Butt, QEH review - daft Biblical whitewashing with great choruses

Even a top soprano and mezzo can’t make this Handel paean wholly convincing

Solomon, OAE, Butt, QEH review - daft Biblical whitewashing with great choruses

Even a top soprano and mezzo can’t make this Handel paean wholly convincing

Two-Piano Gala, Kings Place review - shining constellations

London Piano Festival curators and illustrious friends entertain and enlighten

Two-Piano Gala, Kings Place review - shining constellations

London Piano Festival curators and illustrious friends entertain and enlighten

Echo Vocal Ensemble, Latto, Union Chapel review - eclectic choral programme garlanded with dance

Beautiful singing at the heart of an imaginative and stylistically varied concert

Echo Vocal Ensemble, Latto, Union Chapel review - eclectic choral programme garlanded with dance

Beautiful singing at the heart of an imaginative and stylistically varied concert

Scott, Irish Baroque Orchestra, Whelan, RIAM, Dublin review - towards a Mozart masterpiece

Characteristic joy and enlightenment from this team, but a valveless horn brings problems

Scott, Irish Baroque Orchestra, Whelan, RIAM, Dublin review - towards a Mozart masterpiece

Characteristic joy and enlightenment from this team, but a valveless horn brings problems

Classical CDs: Voice flutes, flugelhorns and froth

Baroque sonatas, English orchestral music and an emotionally-charged vocal recital

Classical CDs: Voice flutes, flugelhorns and froth

Baroque sonatas, English orchestral music and an emotionally-charged vocal recital

Add comment