theartsdesk in Milan: The Farce of Romeo and Juliet at La Scala | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk in Milan: The Farce of Romeo and Juliet at La Scala

theartsdesk in Milan: The Farce of Romeo and Juliet at La Scala

Can theatre management be any worse? But this is Italy

How often has one sat at a first night at the opera or ballet, groaning at missed cues, horrors with costumes, disasters with lighting: one thinks they should surely have got it right by this time? And the rest of the evening is somehow diminished by this upset. But then, how much do we in the audience understand about what it takes to put on a performance, where there are so many elements to co-ordinate and where, therefore, so much conspires to go wrong?

When Deborah MacMillan – Kenneth MacMillan’s widow and minder of his ballets – invited me to find out what happens by joining her team in the run-up to the first night of a new production, I jumped at the chance. I was to take a back seat and be quiet, take notes for Deborah, watch the stage picture intently for details that needed attending to, and fetch and carry.

The venue - the world-renowned Teatro alla Scala, Milan. The production – a new design of MacMillan’s great Romeo and Juliet. The premiere - down for 25 June, but... this is Italy.

The Story So Far

This new production was asked for by the La Scala management to replace their previous 1995 setting for the MacMillan choreography designed by Ezio Frigerio and Franca Squarciapino, which was grand and glamorous but impossible to tour, which was the specific new requirement. The new designers, husband-and-wife team of Mauro Carosi and Odette Nicoletti, were La Scala’s choice; they have worked several times at the theatre and are well known and respected throughout Europe, not only Italy.

It’s been more than a year since they started discussing ideas with Deborah; the final designs were agreed and signed off seven months ago, with every last detail, including the floor plan and elevations, precisely specified and presented. With MacMillan’s choreography already a given, Deborah had insisted that the choreologists teaching and setting the ballet should have plenty of time to work out how to fit and place the steps to the new designs.

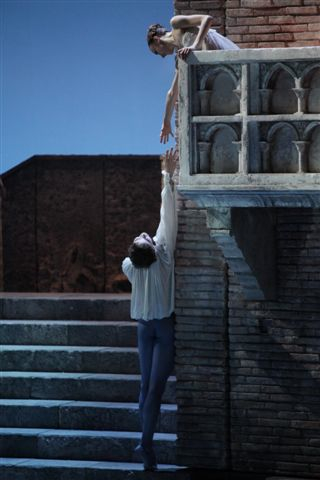

Mauro Carosi’s set is based on the architecture of Verona and its Roman arena: a low sweep of steps running across the back of the stage, with a wide open sky above. On either side of the wings, medieval towers with great doors (which can be moved in or out according to the size of the stages to which La Scala tours), and two complimentary towers mid-stage which move around for different scenes, transforming from the essential balcony to the windows from inside Juliet’s bedroom and finally to the tomb scene, where they frame funereal cypresses.

A simple rood screen with hanging crucifix (by Giotto) is dropped in for Friar Lawrence’s chapel; likewise the gateway to the Capulet’s house (pictured left) and the curtains and screens for the antechamber where Juliet is introduced to Paris. For the ballroom scene add grand candelabra strung with swags of greenery and flowers at the top of those ever-present steps, and for the ballet’s opening scenes of Verona going about its business. Put market stalls around and about them – selling salamis, chickens, fish, veg and so on.

A simple rood screen with hanging crucifix (by Giotto) is dropped in for Friar Lawrence’s chapel; likewise the gateway to the Capulet’s house (pictured left) and the curtains and screens for the antechamber where Juliet is introduced to Paris. For the ballroom scene add grand candelabra strung with swags of greenery and flowers at the top of those ever-present steps, and for the ballet’s opening scenes of Verona going about its business. Put market stalls around and about them – selling salamis, chickens, fish, veg and so on.

Odette Nicoletti’s costumes compliment the medieval-renaissance atmosphere: the marketplace starts pale and sunny – whites and creams for the townsfolk, blue going to green for the Montague boys, red to purple for the Capulets. At the ballroom scene these reds and purples become almost incandescent, heated up with the ladies’ skirts and sleeves swirling about the stage like flames.

Juliet’s dresses are the palest pastels, pink, shot with silver: fragile, ephemeral, certainly young and innocent. Romeo in light blue doublet and hose. Once they are set on their doomed path, the atmosphere, the colours become cooler and cooler: moonlight into the chilly finality of the mausoleum. Deborah MacMillan is very pleased.

The two essential members of her team have been in Milan for some time: Karl Burnett, the choreologist, earlier in the year teaching the steps to the company, which last danced Romeo and Juliet in 2008. Julie Lincoln, who also produces the ballet for the stage, has been there for a week or more polishing the principal dancers and putting the choreography on Mauro’s set, working entrances and exits, placing the extras around and about those steps, using them to the best dramatic effects.

The two essential members of her team have been in Milan for some time: Karl Burnett, the choreologist, earlier in the year teaching the steps to the company, which last danced Romeo and Juliet in 2008. Julie Lincoln, who also produces the ballet for the stage, has been there for a week or more polishing the principal dancers and putting the choreography on Mauro’s set, working entrances and exits, placing the extras around and about those steps, using them to the best dramatic effects.

La Scala has had seven months to get the set ready, the costumes have been fitted to their dancers, Mauro and Odette and their assistants have been supervising. There will now be four days in which to get everything working together before the General (dress rehearsal) on Thursday which is in front of an audience - the house is always packed apparently. The dancers need to get used to the stage set and dancing with their costumes, and then to dancing to the sound of the orchestra rather than piano.

But most importantly as far as Deborah MacMillan is concerned – these four days are all-important to get the lighting absolutely right, because it’s the lighting which transforms the dancers, sets and costumes. Take time to get it as perfect as possible and it creates the magic and atmosphere. Get it wrong and...

Sunday

Deborah arrives from London in the evening with news of gossip which Julie Lincoln has heard from some dancer, that the first night on Friday is going to be cancelled because there will be a General Strike. But it’s only a rumour so far.

Monday (four days to go)

Deborah is to spend the morning in the Wardrobe, looking at Odette’s costumes with her. I am to join her at the theatre for lunch and then the afternoon rehearsal with costumes and piano. At about 11.30 I get a message that the afternoon is cancelled. Outside the theatre, the posters advertising that evening’s performance (the second) of the new production of Gounod’s Faust are pasted with white notices announcing the show is cancelled because of industrial action. It seems the theatre is seething with dissent: there are knots of agitated people huddled in corners hissing and haranguing.

It's reported that the Sovrintendente fled from the theatre and has gone into hiding

The first night of Faust on the previous Friday was distinguished by the refusal of the Chorus, only half an hour before curtain-up, to perform either in costume or in their roles. Apparently they sang their parts straight out at the audience, standing in a line in their day clothes with their briefcases and backpacks – while the audience catcalled and booed.

Deborah reports that the Makhar Vaziev, Director of the Ballet, was appalled, had never seen anything like it and couldn’t believe how the theatre was treating its audience.

However Gastón Fournier-Facio, the Artistic Co-ordinator and number two in the La Scala artistic hierarchy, who passed by while rushing to catch a plane for London and the opening of Massenet’s Manon at Covent Garden (a La Scala co-production), apparently was airily sanguine about it all. Deborah wasn’t to worry, nothing would happen to La Scala, everything would be all right on the night – they always got things together when it mattered.

No-one from the Management says anything about a strike cancelling the first night. Or even the possibility of a cancelled first night. Nobody says anything about the other industrial action in the theatre. Julie Lincoln continues to rehearse the dancers: she has five casts to coach in their roles.

No-one from the Management says anything about a strike cancelling the first night. Or even the possibility of a cancelled first night. Nobody says anything about the other industrial action in the theatre. Julie Lincoln continues to rehearse the dancers: she has five casts to coach in their roles.

In the evening we all have dinner together. Julie still hears from the dancers’ grapevine that the first night will be cancelled: it’s the day of a nationwide General Strike. But she’s heard that the other strikes are to do with the theatre unions: the Italian Government has announced the end to central funding for lyric theatres except for La Scala and the Accademia di Santa Cecilia which are deemed to be national assets. La Scala’s unions are acting in sympathy with the other theatres around the country facing the cuts, but unfortunately they can’t agree how to do it among themselves, so that increases the chaos. Nobody knows who will be working and when, at any point.

Meanwhile, it is said that Stéphane Lissner, the Sovrintendente – General Manager and Artistic Director of La Scala - has fled from the the theatre after his office was invaded by an angry crowd of technicians and has gone into hiding. We also hear that he has never established the Management's control over the unions, who run rings around him.

Tuesday (three days to go)

The morning session is down for technical and lighting: but as Monday’s session with set and costumes together was lost, there is really nothing to light until the afternoon rehearsal. This is with costumes and piano, the orchestra will join in the evening. They have been rehearsing in another place with the American conductor Kevin Rhodes.

There will be a lighting session running all night, from midnight to 6am

Mauro apologises to Deborah that the set will not look as it should, because he is still waiting for a projector system which will transform the cyclorama with images of real sky and clouds - as she would have seen in the designs. At the moment it is a dead cream colour overwhelming the back of the stage. Apparently the Technical Director, Franco Malgrande, alternates between agreeing and not agreeing to have the projections, even though they were in the designs signed off with La Scala seven months previously.

Mauro’s specified projectors, simple, and well-tried, were rejected as old-fashioned and expensive. But even with a state-of-the-art machine to be hired instead, with the theatres currently suffering from strikes, Malgrande wants to wait and see what might be happening so that he doesn’t have to pay unnecessary hire fees if the performances were to be cancelled.

Understandably, the first run-through leaves a lot to be sorted: everyone is nervous – and more so now with time being lost. Dancers fuss with their costumes, stage hands take their time, cues are missed, and people constantly walk across lights sending huge shadows on the cyc. Two major lighting issues need urgent attention: the powerful opening to the Capulet ballroom scene (pictured left) needs a dramatic revelation of the massed ranks of dancers in their reds and purples, before advancing towards the audience. It has to be a precise co-ordination of curtain, lights and music. And with Friar Lawrence, the smooth music needs a soft fade-in of light to match: at the moment, the candles on his rood screen just click on jarringly.

Understandably, the first run-through leaves a lot to be sorted: everyone is nervous – and more so now with time being lost. Dancers fuss with their costumes, stage hands take their time, cues are missed, and people constantly walk across lights sending huge shadows on the cyc. Two major lighting issues need urgent attention: the powerful opening to the Capulet ballroom scene (pictured left) needs a dramatic revelation of the massed ranks of dancers in their reds and purples, before advancing towards the audience. It has to be a precise co-ordination of curtain, lights and music. And with Friar Lawrence, the smooth music needs a soft fade-in of light to match: at the moment, the candles on his rood screen just click on jarringly.

Marco says they will look for a machine to do it: it’s possible they might find one in Milan for the morning.

At this stage the phalanx of people around the production desks are all there to watch as much detail as possible, each concentrating on their patch and making notes of what needs adjusting and changing. I come away with 10 pages of notes from Deborah MacMillan. Mauro and Odette have similar, so do Julie and Laura, the ballet mistress.

In the evening, the energy levels are transformed: Kevin Rhodes driving a supercharged orchestra – snappy rhythms, good strong bass lines, colour and energy. In the break he explains he has to whip them along because the personnel keeps changing from one rehearsal to the next. But he’s been assured that this evening’s ensemble will be the same as for the performances (something to be thankful for).

Mauro’s assistant tells us there will be a lighting session running all night, from midnight to 6am.

It is the most peculiar experience: sitting in the dark, empty theatre watching infinitesimal adjustments to the light on the set; adjusting the focus, softening the shape with "barn doors" or gobos, trying the same effect but from different angles. In Juliet’s bedroom, there is a crucifix that is central to the action as she prays before it briefly before summoning up the courage to swallow Friar Lawrence’s sleeping potion. It’s probably a 10-second moment in the ballet – and the audience must have registered that the crucifix there to make it work. But make it too blatant and it interferes with the other part of the narrative – the great, passionate bedroom pas de deux.

It takes Marco Filibeck nearly an hour to get the effect he wants: a slow process of trying lamp after lamp, an agonising wait in between each change. He apologises: there is only one person working up in the flies to find the right lamp and to do the focusing. His fellow technician has declined to turn up. Meanwhile, there is a mess of lighting arrangements to have to sort through and work around because of the new Faust production which was all set the week before.

It takes Marco Filibeck nearly an hour to get the effect he wants: a slow process of trying lamp after lamp, an agonising wait in between each change. He apologises: there is only one person working up in the flies to find the right lamp and to do the focusing. His fellow technician has declined to turn up. Meanwhile, there is a mess of lighting arrangements to have to sort through and work around because of the new Faust production which was all set the week before.

Occasionally stage hands materialise to move the set. Or to stand in it so they can be lit within the space. Marco whispers into his headset: slowly something changes. I think about watching paint dry. At about 1.30am there is a pause. The seats in La Scala are beginning to be very annoying: the back support just lacking, leg room not quite long enough. Milan is also a very damp city, from wet rice fields of the Po Valley, the dampness aggravating the aches and pains from sitting for long hours. There are also biting insects in the theatre.

At 3am, the technicians and stage crew pull the plugs on the session. Marco and Mauro have got close to what they want for the intimate scenes – the balcony, the bedroom and the tomb. But only the basics are there for the crowd scenes – there’s very little to be done without the dancers and their costumes and without the all-important back projections.

Wednesday (two days to go)

The Friar Lawrence rood screen is down at the start of the session: men are fixing a switching system which will fade up the candles as the light comes onto the big hanging crucifix. It looks beautiful.

Deborah MacMillan issues an ultimatum that she will withdraw the licence for La Scala to perform MacMillan

But the machine for the back projections is still not in the theatre. Mauro is getting very anxious that his design concepts are now being seriously compromised. He shows us exactly how the designs were presented to the theatre – and agreed by La Scala those seven months previously. It seems they are now suggesting that his designs don’t explain that the sky effects were to be real images projected which is why there is no projector booked.

Deborah MacMillan goes very quiet at hearing this and leaves the stalls: the designs were sent to the MacMillan office at the same time; she knows very well what was specified in them, immaculately drawn up by Mauro’s assistant who has enormous experience of working in film as well as theatre.

When she returns, she tells Mauro she’s issued an ultimatum to the Ballet Office that if Mauro and Odette or any of the production team feel that their work is being traduced by La Scala’s current practices, she will have no hesitation in withdrawing the licence for La Scala to perform MacMillan. She told the office that MacMillan’s choreography is well enough established to hold its own, but that freelance designers are dependent on the reviews for the work they are currently doing and that she will not tolerate their creativity being abused, least of all by the Technical Department which should be there to give them exactly what is needed for the production.

When she returns, she tells Mauro she’s issued an ultimatum to the Ballet Office that if Mauro and Odette or any of the production team feel that their work is being traduced by La Scala’s current practices, she will have no hesitation in withdrawing the licence for La Scala to perform MacMillan. She told the office that MacMillan’s choreography is well enough established to hold its own, but that freelance designers are dependent on the reviews for the work they are currently doing and that she will not tolerate their creativity being abused, least of all by the Technical Department which should be there to give them exactly what is needed for the production.

In the afternoon, the stage crew blows slowly hot and cold. At one point Julie Lincoln comes on stage to announce that there’s no one working stage right. The monks filing in from each side to the mausoleum have their flares lit on one line but not the other.

The note-taking is now getting hilarious: as one thing is put right so another goes wrong.

The rehearsal is scheduled to end at 4pm because of the evening performance of Faust. But that is cancelled because of industrial action. Another all-night lighting session is booked - but Mauro suggests Deborah doesn’t come as it won’t start till 3.30am.

Thursday (one day to go)

The cypress trees for the last scene have arrived from the other side of Milan. They have been waiting for a truck which has been affected by the strikes. A projector for the sky has also arrived, much to the surprise and displeasure of La Scala’s Technical Manager Franco Malgrande. But it’s the wrong one, only working with stills.

I discover that in recent weeks La Scala lost the first nights of three other productions

It’s now public that tomorrow’s premiere is off with the General Strike, with no technicians working during the day. However no-one from the Management has told the team anything.

Meanwhile, tonight’s public Dress Rehearsal will not have all the technical aspects called for in the design and Mauro says he now will have to come back to Milan on Monday before the performance - which will now be the new “premiere” – for those last-minute adjustments now not possible because of the strike.

The Ballet Office is most reluctant to agree to pay the extra expense of his train fare back to Milan and the extra hotel night. Luckily, Deborah is with him to intervene. She points out that La Scala has already lost umpteen thousands from the Faust cancellations: they could just be about to lose into the millions if she removes Romeo.

This was not an idle threat. With exquisite timing, she had just postponed the opening performance of Manon at the Teatro Colon in Buenos Aires where Karl Burnett had also been struggling with other union problems. It would not be performed until they have properly rehearsed all the elements of the work. I later discover that in recent weeks La Scala lost the first nights of three other productions - Barenboim’s Rheingold (a new production), a ballet triple bill, and The Barber of Seville – with three Fausts cancelled in total and one performance with Placido Domingo in Simon Boccanegra.

This was not an idle threat. With exquisite timing, she had just postponed the opening performance of Manon at the Teatro Colon in Buenos Aires where Karl Burnett had also been struggling with other union problems. It would not be performed until they have properly rehearsed all the elements of the work. I later discover that in recent weeks La Scala lost the first nights of three other productions - Barenboim’s Rheingold (a new production), a ballet triple bill, and The Barber of Seville – with three Fausts cancelled in total and one performance with Placido Domingo in Simon Boccanegra.

We are told there will be an extra technical lighting rehearsal on Monday, at 1pm in the afternoon.

There is great excitement just before the public is let in for the General: stage management tells Julie and Deborah that the big candelabra and festive swags have arrived for the Capulet Ballroom scene – but unfortunately there is no trolley yet to get them on and off the set quickly, so there is a discussion about extra music to cover the gap.

However when it comes to it, there are no swags or candelabra: there’s a dispute going on backstage as to which union team does what with them, so they don’t bother with them at all.

And the dramatic effect of the scarlet and purple Capulet party guests, which Julie Lincoln has brilliantly set to fill the stage and billow up the steps at the back in order to make a very menacing advance on the audience, is blown away by no lighting effect at all on the cyc, which is now turned a dirty yellow with the dazzling colour below. There is a lot of work still to be done to get the magic and atmosphere on the set and to get the colours in Odette’s costumes to start singing as they should.

And the dramatic effect of the scarlet and purple Capulet party guests, which Julie Lincoln has brilliantly set to fill the stage and billow up the steps at the back in order to make a very menacing advance on the audience, is blown away by no lighting effect at all on the cyc, which is now turned a dirty yellow with the dazzling colour below. There is a lot of work still to be done to get the magic and atmosphere on the set and to get the colours in Odette’s costumes to start singing as they should.

Everyone has a lot of wine at supper after.

Friday (opening night - not)

The theatre is closed, but Mauro’s assistant is staying over till Saturday to try to sort out the projector. Another machine has arrived, but again it’s wrong - too weak to work with theatre lighting. La Scala’s Technical Department still appears not to have understood the technical necessities nor, critically, the time it takes to get it right - as Deborah crisply points out, from her experiences of film and projection in MacMillan’s ballets, not least with her recent production of Isadora at Covent Garden when this technical aspect was sorted out in the theatre itself, six months before the show.

The Assistant Technical Director has been discovered surfing the net, trying to find pictures of moving clouds to download

Furthermore the machine hasn’t come with the software needed to project actual skyscapes of changing clouds. Apparently the Assistant Technical Director has been discovered surfing the net, trying to find pictures of moving clouds to download. The best so far comes from a Simon & Garfunkel song – but unfortunately two heads appear in the middle of the image at a crucial point. An SOS has been emailed around to colleagues in the Rome film studios to find the right images.

Deborah has now also discovered that the Technical Director Franco Malgrande actually cancelled the projectors specified by Mauro only a fortnight before the scheduled first night. It might be possible for dancers, music, sets and costumes to gather themselves together at the last minute to pull a performance out the bag in spite of all the industrial action, but for the theatre itself to pull a crucial element of the stage picture is quite another kind of betrayal.

Julie Lincoln also stays over the weekend for the Monday premiere – she has plenty to do with the other casts. After dinner on Sunday night we book a table at the restaurant for a post-performance meal on Monday. The waiters roar with laughter and tell us there will be no performance – everyone in Milan knows the theatre will be on strike.

Except the production team. So far, no-one from the top management has been near Deborah, or Julie or Mauro and Odette to explain what has been going on, or to apologise or in anyway mitigate the circumstances. Or even to welcome them to the theatre.

Monday (new opening night)

During the morning, quite by chance, Deborah meets Gastón Fournier-Facio, the Artistic Coordinator, in the management offices as she is doing final business at the Ballet Office. She tells him that she has never ever encountered such incompetent and disgraceful behaviour in a major theatre: that indeed the most insignificant of amateur theatre companies would be embarrassed if they had been responsible for what the Romeo team has had to endure in the past week.

Managers are very good at spreading the word about difficult artists and demanding directors

He is horrified; apparently he denies that he has heard of any problems in the theatre. But most of all he doesn’t like to hear her talking about La Scala in such derogatory terms. So apparently she says she’ll tell him again – and does.

He is running to catch a plane to Berlin where he is to take part in the press conference announcing the next stage of Wagner’s Ring cycle, which is a co-production with Daniel Barenboim’s opera house. He says he will call Deborah from the airport at 3pm to make sure that everything is OK for the first night. He doesn’t.

We gather in the theatre at 1pm. The tabs are up, safety curtain up and the stage is full of the Faust set. There was a performance in the diary on Saturday, which was cancelled by a strike. But they still went ahead building the set; now they’re striking it. All according to the book.

Gradually, it all changes to Romeo, Act 3, which finally appears around about 3.30. They will be working on the lighting backwards to the opening. They have till 7pm. The performance starts at 8pm.

But Julie and Laura arrive with information that tonight’s performance is still in question: the dancers have agreed to perform, but the musicians and technicians will meet at 4pm to vote on what they will do. In the event, they will do the show, but the musicians will make their protest by playing in street clothes.

But Julie and Laura arrive with information that tonight’s performance is still in question: the dancers have agreed to perform, but the musicians and technicians will meet at 4pm to vote on what they will do. In the event, they will do the show, but the musicians will make their protest by playing in street clothes.

Mauro has been viewing cloud images: apparently the theatre has now bought hours of changing sky! It all looks good on the monitor, but unfortunately there’s much more work still needed to get the images strong enough in the theatre.

Deborah now agitates that they should work on the important dramatic moments to get their impact right. She also asks for a translator from the Ballet Office so that everyone can understand what’s going on. Achingly slowly, Marco gets the atmospheres: the chilly mausoleum with flickering sconces on the tombs, the candles fade up and down magically at Friar Lawrence’s, moonlight in the bedroom with the crucifix, the balcony scene with its shadows and pools of light – and the drama of the Capulet party. There are swags and candelabra!

I suggest to the person from the Ballet Office that it would be a great lesson if everyone wanting to work in management was actually to be forced to sit through the hours and days of painstaking work that goes into one of their shows, to understand the complexities of how it works. She doesn’t look too pleased at the idea. But I have been reading the CVs of La Scala’s top management, which list a great deal of paper-pushing executive activity, talk and inter-executive social mingling, but very little evidence of actually getting down and dirty with the hard work of making theatre work, and especially under difficult circumstances. And of course managers are also very good at spreading the word among themselves about difficult artists and demanding directors.

I suggest to the person from the Ballet Office that it would be a great lesson if everyone wanting to work in management was actually to be forced to sit through the hours and days of painstaking work that goes into one of their shows, to understand the complexities of how it works. She doesn’t look too pleased at the idea. But I have been reading the CVs of La Scala’s top management, which list a great deal of paper-pushing executive activity, talk and inter-executive social mingling, but very little evidence of actually getting down and dirty with the hard work of making theatre work, and especially under difficult circumstances. And of course managers are also very good at spreading the word among themselves about difficult artists and demanding directors.

The astonishing fact about this experience for me was Laura and her dancers getting on with the rehearsals, and then the performance, despite all the technical nonsense going on around them; and that everyone working in Mauro’s and Odette’s teams, and working with Deborah, was more or less sanguine about what was going on. Mauro just shrugged his shoulders and said the managerial behaviour is pretty much the same wherever you go in Europe – particularly where civil servants rule the roost. La Scala has just got worse over recent years as it increasingly trumpets its reputation as the world’s most important opera house. Or was, once upon a time.

The conductor enters the pit in his evening dress, his orchestra in shorts and T-shirts

At 8pm, the theatre is full with Milan in its finery. Kevin Rhodes enters the pit in his evening dress, his orchestra in shorts and T-shirts. I wondered whether they were the faces he expected to see.

So the bustle of the market starts, the swashbuckling swordfights, Juliet and the nurse and meeting the unlucky Paris. The team holds its breath before the opening to the Capulet’s ball - which seems to go pretty well – swags and candelabra more or less all present. The change to the Balcony scene works its magic – until someone knocks a fader and a great streak of white light blares across the stage.

And you could hear everyone in the theatre thinking, “For goodness' sake, why can’t they get something as basic as that right?”

- More news: Lissner threatens to close La Scala down

- theartsdesk letter from Rome on uproar at the Accademia di Santa Cecilia

- theartsdesk feature and interview with Jann Parry about her biography of Kenneth MacMillan, 'Different Drummer'

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Dance

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

R:Evolution, English National Ballet, Sadler's Wells review - a vibrant survey of ballet in four acts

ENB set the bar high with this mixed bill, but they meet its challenges thrillingly

R:Evolution, English National Ballet, Sadler's Wells review - a vibrant survey of ballet in four acts

ENB set the bar high with this mixed bill, but they meet its challenges thrillingly

Like Water for Chocolate, Royal Ballet review - splendid dancing and sets, but there's too much plot

Christopher Wheeldon's version looks great but is too muddling to connect with fully

Like Water for Chocolate, Royal Ballet review - splendid dancing and sets, but there's too much plot

Christopher Wheeldon's version looks great but is too muddling to connect with fully

iD-Reloaded, Cirque Éloize, Marlowe Theatre, Canterbury review - attitude, energy and invention

A riotous blend of urban dance music, hip hop and contemporary circus

iD-Reloaded, Cirque Éloize, Marlowe Theatre, Canterbury review - attitude, energy and invention

A riotous blend of urban dance music, hip hop and contemporary circus

How to be a Dancer in 72,000 Easy Lessons, Teaċ Daṁsa review - a riveting account of a life in dance

Michael Keegan-Dolan's unique hybrid of physical theatre and comic monologue

How to be a Dancer in 72,000 Easy Lessons, Teaċ Daṁsa review - a riveting account of a life in dance

Michael Keegan-Dolan's unique hybrid of physical theatre and comic monologue

A Single Man, Linbury Theatre review - an anatomy of melancholy, with breaks in the clouds

Ed Watson and Jonathan Goddard are extraordinary in Jonathan Watkins' dance theatre adaptation of Isherwood's novel

A Single Man, Linbury Theatre review - an anatomy of melancholy, with breaks in the clouds

Ed Watson and Jonathan Goddard are extraordinary in Jonathan Watkins' dance theatre adaptation of Isherwood's novel

Peaky Blinders: The Redemption of Thomas Shelby, Rambert, Sadler's Wells review - exciting dancing, if you can see it

Six TV series reduced to 100 minutes' dance time doesn't quite compute

Peaky Blinders: The Redemption of Thomas Shelby, Rambert, Sadler's Wells review - exciting dancing, if you can see it

Six TV series reduced to 100 minutes' dance time doesn't quite compute

Giselle, National Ballet of Japan review - return of a classic, refreshed and impeccably danced

First visit by Miyako Yoshida's company leaves you wanting more

Giselle, National Ballet of Japan review - return of a classic, refreshed and impeccably danced

First visit by Miyako Yoshida's company leaves you wanting more

Quadrophenia, Sadler's Wells review - missed opportunity to give new stage life to a Who classic

The brilliant cast need a tighter score and a stronger narrative

Quadrophenia, Sadler's Wells review - missed opportunity to give new stage life to a Who classic

The brilliant cast need a tighter score and a stronger narrative

The Midnight Bell, Sadler's Wells review - a first reprise for one of Matthew Bourne's most compelling shows to date

The after-hours lives of the sad and lonely are drawn with compassion, originality and skill

The Midnight Bell, Sadler's Wells review - a first reprise for one of Matthew Bourne's most compelling shows to date

The after-hours lives of the sad and lonely are drawn with compassion, originality and skill

Ballet to Broadway: Wheeldon Works, Royal Ballet review - the impressive range and reach of Christopher Wheeldon's craft

The title says it: as dancemaker, as creative magnet, the man clearly works his socks off

Ballet to Broadway: Wheeldon Works, Royal Ballet review - the impressive range and reach of Christopher Wheeldon's craft

The title says it: as dancemaker, as creative magnet, the man clearly works his socks off

The Forsythe Programme, English National Ballet review - brains, beauty and bravura

Once again the veteran choreographer and maverick William Forsythe raises ENB's game

The Forsythe Programme, English National Ballet review - brains, beauty and bravura

Once again the veteran choreographer and maverick William Forsythe raises ENB's game

Comments

...

...

...

...