theartsdesk in Paris - following in the footsteps of Gounod | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk in Paris - following in the footsteps of Gounod

theartsdesk in Paris - following in the footsteps of Gounod

Two operatic rarities prove that a revival is long overdue

It’s a truism that history is written by the victors, but nowhere in classical music is the argument made more persuasively than in the legacy and reputation of Charles Gounod.

It’s a sign of just how far out of fashion Gounod has fallen that none of the major British houses is taking the opportunity to stage one of his operas. A revival of David McVicar’s production of Faust at the Royal Opera next year feels like too little too late for one of the 19th century’s greats – a composer whose conservative style and reputation was swept aside in the all-consuming flood of Wagnerian innovation. Famous detractors (including Wagner himself, as well as Debussy) have done further damage, leaving Gounod’s reputation balanced precariously on little more than Faust, Romeo et Juliette and the ubiquitous "Ave Maria".

Gounod’s heavy, magnificent Romantic opera has been scrubbed and stripped back to the white wood hidden beneath many years of stain and varnish

But in the composer’s native France the anniversary is drawing more attention. Earlier this month, Gounod was the focus of the Palazetto Bru Zane’s annual Paris festival, showcased as a symphonist and composer of sacred music as well as for his operas. Inevitably, however, it’s the latter that dominated, with a rare staging of the composer’s notorious La Nonne Sanglante and the world premiere of a brand-new edition of Faust – the first chance to hear the work stripped of its now-traditional revisions and restored to the composer’s startlingly different first thoughts.

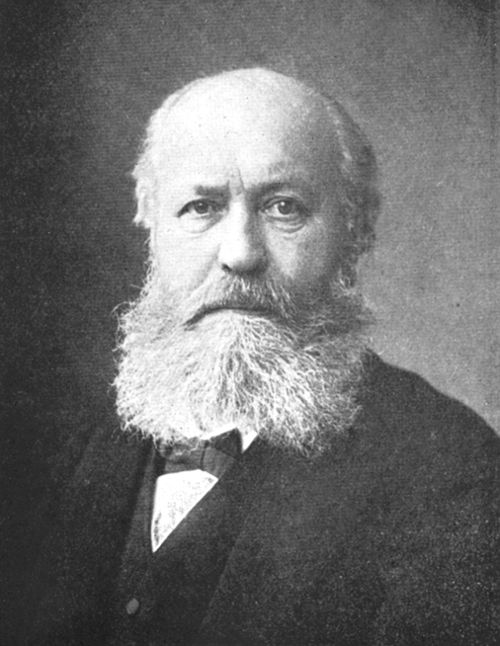

It’s hard to walk through Paris and not find yourself treading in Gounod’s footsteps. The composer’s life criss-crossed the city for over 70 years, measured out in architectural milestones right across Paris. You can follow Gounod (pictured below) from his birth in the leafy Place Saint-Andre-des-Arts and the Paris Conservatoire, where he began his studies in 1836, to his adult home in the Rue Vaneau (where he was, incidentally, a neighbour of the young Karl Marx) to the Eglise des Missions Etrangeres with its elegant 17th century façade where he was organist, and the seminary of Saint Sulpice where the composer briefly studied theology and toyed with the idea of joining the priesthood.

Perhaps most evocative, however, is the Rue d’Ankara, out in the smart 16th arrondissement in the western corner of the city, where “poor, mad Gounod” (as Berlioz described him) lived for a few weeks in a clinic as the patient of the famous Dr Emile Blanche. Mental instability dogged the composer throughout his life, manifesting itself in “cerebral fevers” that would force him to his bed, but would also, perhaps, become the source for the rich, complicated psychology of his operas – for Marguerite’s terrible, murderous confusion, and Sapho’s suicidal desperation.

Perhaps most evocative, however, is the Rue d’Ankara, out in the smart 16th arrondissement in the western corner of the city, where “poor, mad Gounod” (as Berlioz described him) lived for a few weeks in a clinic as the patient of the famous Dr Emile Blanche. Mental instability dogged the composer throughout his life, manifesting itself in “cerebral fevers” that would force him to his bed, but would also, perhaps, become the source for the rich, complicated psychology of his operas – for Marguerite’s terrible, murderous confusion, and Sapho’s suicidal desperation.

But it’s not the various apartments he occupied nor even this latter address, which framed his personal nadir, that tells us most about Gounod. He may have lived in addresses across the city, but his true homes were Paris’s opera house – the scenes of his greatest professional successes and personal triumphs as well as his most demoralising public failures.

Faust was, of course, Gounod’s most famous triumph. Its performance at the Paris Opera in 1869 established the work’s reputation internationally, and for a long time it was the house’s most-performed opera. But the version the Parisian audience witnessed that night – the work we know today, complete with a ballet, sung recitatives and the now-traditional sequence of arias and ensembles – is a long way from the score premiered a decade earlier at the city’s Theatre Lyrique. That this earlier version was rejected by the Paris Opera tells you much about the light-footed 1859 account, an altogether more mercurial work than its later counterpart.

Performed by Christophe Rousset and Les Talens Lyriques, this contemporary premiere of the “original” Faust is based on a new edition shortly to be published by Barenreiter. Paul Prevost (also editor of the 1869 Faust) has put together an unusual score that exposes the many layers of musical archaeology concealed beneath the surface of this familiar work. The edition allows performers to recreate the 1859 premiere but, perhaps more interestingly, it also enables them to create a variety of palimpsest versions of the score, incorporating the significant music excised before the premiere as well as that added inafterwards.

The account we heard here at the Theatre des Champs-Elysees (soon also to be recorded and released by Les Talens Lyriques) was musical collage intended to offer the greatest amount of “new” music (including a duet for Marguerite and Valentin before the latter’s departure for war, an exquisite aria for Siebel, a light, characterful trio for Wagner, Siebel and Faust, and a slick new tavern song – “Maitre Scarabee” – for Mephistopheles) while still creating a satisfying dramatic and musical whole.

But even more striking than the unfamiliar numbers (and the absence of some very familiar ones, such as Mephistopheles’s “Le Veau d’or” or Valentin’s “O saint medaille”) is the change in tone and pace generated by the return to the work’s original spoken dialogue, together with the melodramas that bridge the gap between these and the sung passages.

Suddenly secondary figures like Dame Marthe come off the page, fleshed into real human detail and interest. The latter becomes a wonderfully garrulous, gossipy, ghastly old lady, whose attempted seduction of Mephistopheles offers brutally jagged counterpoint to Marguerite’s tragic loss of virtue. Wagner, Valentin and Siebel too are given new space and time dramatically, as well as new music. The result puts the tragic plot in fresh counterpoint and balance with comic sub-plot, creating not an opera demi-caractere. (Pictured above: Veronique Gens, who plays Marguerite)

Two operas, two very different musical worlds, and one persistent question: when is the long-overdue Gounod revival going to get underway?

The change that really swings the balance, however, is the role of Mephistopheles, whose new dialogue (rich in knowing asides to the audience, wooing us along with Faust, implicating us at every step in his actions) helps shape a villain whose smooth, self-deprecating charm (truly a fantome adorable et charmant) is far more insidious a weapon than the blunt-force attacks of his later incarnation. A different tone requires a different voice, and from the sinister vocal smile of his opening “Me voici”, the casting of Andrew Foster-Williams here completed the transformation from a looming, booming bass-baritone to a singer closer to a baryton de caractère – lighter and more nimble vocally, more playful in his characterisation and treatment of text.

The necessary counterweight to so much lightness was Veronique Gens’s Marguerite. No empty-headed virgin, this heroine had a stature – both vocally and dramatically – that rooted the drama in tragedy, that kept it from straying from the very real moral dilemma at the heart of the piece. Matching the grainy textural details of Rousset’s period orchestra, Gens gave us the innocence of stern moral conviction rather than of foolish incomprehension. Her Jewel Song (which, in this edition, gains some 30 bars) had real wonder to it, born out of text cherished and handled with such vocal care, but it was in the later Acts that she really came into the own – in the horrified realisation of “Il ne revient pas” (its pathos spiced by the reinstatement of Siebel’s tender answering romance “Versez vos chagrins dans mon ame”) and the cruel drama of the church scene.

Playing the straight man to Foster-Williams’s comic devil, Benjamin Bernheim’s Faust is less world-weary than most. Easy and unstrained right to the top of the voice, Bernheim’s lovely instrument spun Faust’s “Salut, demeure chaste et pure” from beaten gold – airy and glowing from within – draping Les Talens Lyriques’ translucent accompaniment in the finest of melodic cloths. But if individual voices helped (re-)animate this 1859 Faust, the heart of this newly restored work was the orchestra. It’s as though Gounod’s heavy, magnificent Romantic opera has been scrubbed and stripped back to the white wood hidden beneath many years of stain and varnish. The work’s structural silhouette may still be sprawling and weighty, but its impression is one of new elegance, its musical pleasantly mottled with light and shade. Rousset’s 19th century brass add their rough, whooping shouts to the military episodes, while the jangling period harp is altogether more volatile than its contemporary counterpart – offering a fragile, uncertain vision of beauty and love. Above all, the strings – sinewy, lean, deft – allow us the opportunity to hear all of this detail, never smothering or dulling Gounod’s skilful orchestration.

But if individual voices helped (re-)animate this 1859 Faust, the heart of this newly restored work was the orchestra. It’s as though Gounod’s heavy, magnificent Romantic opera has been scrubbed and stripped back to the white wood hidden beneath many years of stain and varnish. The work’s structural silhouette may still be sprawling and weighty, but its impression is one of new elegance, its musical pleasantly mottled with light and shade. Rousset’s 19th century brass add their rough, whooping shouts to the military episodes, while the jangling period harp is altogether more volatile than its contemporary counterpart – offering a fragile, uncertain vision of beauty and love. Above all, the strings – sinewy, lean, deft – allow us the opportunity to hear all of this detail, never smothering or dulling Gounod’s skilful orchestration.

Where Faust gave us an unfamiliar perspective on familiar Gounod, a fully staged production of the composer’s La Nonne Sanglante at Paris’s Opera Comique (a co-production with Laurence Equilbey and her Insula orchestra and the Palazetto Bru Zane) offered us classic Gounod style in a thrillingly unfamiliar work. Rarely performed owing to the unremitting musical challenges of its central tenor, an under-written soprano lead and a libretto that creaks and howls more vividly than any Gothic ghouls in the attic, La Nonne Sanglante is nevertheless a startlingly good score. Infighting and regime-change at the Paris Opera saw it decried as “filth”, condemning its future in the repertoire, but this had less to do with the work itself and more to do with operatic politicking. (Pictured above: Michael Spyres with Vannina Santoni as Agnes and Marion Lebegue as La Nonne)  A five-act behemoth that should collapse under its own weight and the kitsch excesses of a plot based on Matthew Lewis’s deliciously lurid novel The Monk is sustained by sheer musical invention. Both the orchestration and the melodic writing of this early work (premiered some five years before Faust) are full of surprise and charm, whether in the sparky coloratura numbers for page-boy Arthur (a trouser role for soprano taken here with verve and precision by Jodie Devos), the breath-taking sequence of tenor arias for Rodolphe or the lowering clouds of low brass and chromatic lightning flashes that colour the music of the bleeding nun herself.This new production by David Bobee pulls off the feat of honouring the work’s Gothic milieu and mood while avoiding pantomime. Game of Thrones-style costuming nods to the story’s medieval setting but is briskly tempered by monochromes and minimalist design. The effect is a bit sci-fi and a bit Narnia – a dramatic backdrop just engaging enough to hold the attention while keeping the score in the spotlight, framing dancers and the chorus singers from Equilbey’s accentus choir in a sequence of memorable tableaux.

A five-act behemoth that should collapse under its own weight and the kitsch excesses of a plot based on Matthew Lewis’s deliciously lurid novel The Monk is sustained by sheer musical invention. Both the orchestration and the melodic writing of this early work (premiered some five years before Faust) are full of surprise and charm, whether in the sparky coloratura numbers for page-boy Arthur (a trouser role for soprano taken here with verve and precision by Jodie Devos), the breath-taking sequence of tenor arias for Rodolphe or the lowering clouds of low brass and chromatic lightning flashes that colour the music of the bleeding nun herself.This new production by David Bobee pulls off the feat of honouring the work’s Gothic milieu and mood while avoiding pantomime. Game of Thrones-style costuming nods to the story’s medieval setting but is briskly tempered by monochromes and minimalist design. The effect is a bit sci-fi and a bit Narnia – a dramatic backdrop just engaging enough to hold the attention while keeping the score in the spotlight, framing dancers and the chorus singers from Equilbey’s accentus choir in a sequence of memorable tableaux.

You don’t stage La Nonne Sanglante unless you have a star tenor, and in Michael Spyres Equilbey and Bobee have that in spades – a once-in-a-generation voice that doesn’t just cope with but actively relishes the stratospheric tessitura and formidable technical demands of the role. With no arias assigned to his love-interest Agnes (soprano Vannina Santoni, silvery-strong in the duets), the tenor must carry the show, supported by colourful musical cameos from Pierre the Hermit, whose incense-perfumed music anticipates the spiritual episodes of Faust, and the Bleeding Nun herself. Mezzo Marion Lebegue found both the cruelty and the pain in a character who is at once victim and villain, opening up surprising psychological ambiguity in the piece, and adding another strong argument in its favour.Where Les Talens Lyriques gave us crisp clarity, Equilbey and Insula offered depth and richness, painting sonic slashes of red through Bobee’s monochromes, and balancing the heady brilliance and agility of Spyres’ tenor with meaty instrumental weight. This isn’t the lean, clean, classical Gounod of the 1859 Faust and it’s all the better for it.

Two operas, two very different musical worlds, and one persistent question: when is the long-overdue Gounod revival going to get underway? Wagner may have had the last word, but France’s Romantic still has plenty to say. 200 years later maybe it’s about time we started listening.

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Opera

The Makropulos Case, Royal Opera - pointless feminist complications

Katie Mitchell sucks the strangeness from Janáček’s clash of legalese and eternal life

The Makropulos Case, Royal Opera - pointless feminist complications

Katie Mitchell sucks the strangeness from Janáček’s clash of legalese and eternal life

First Person: Kerem Hasan on the transformative experience of conducting Jake Heggie's 'Dead Man Walking'

English National Opera's production of a 21st century milestone has been a tough journey

First Person: Kerem Hasan on the transformative experience of conducting Jake Heggie's 'Dead Man Walking'

English National Opera's production of a 21st century milestone has been a tough journey

Madama Butterfly, Irish National Opera review - visual and vocal wings, earthbound soul

Celine Byrne sings gorgeously but doesn’t round out a great operatic character study

Madama Butterfly, Irish National Opera review - visual and vocal wings, earthbound soul

Celine Byrne sings gorgeously but doesn’t round out a great operatic character study

theartsdesk at Wexford Festival Opera 2025 - two strong productions, mostly fine casting, and a star is born

Four operas and an outstanding lunchtime recital in two days

theartsdesk at Wexford Festival Opera 2025 - two strong productions, mostly fine casting, and a star is born

Four operas and an outstanding lunchtime recital in two days

The Railway Children, Glyndebourne review - right train, wrong station

Talent-loaded Mark-Anthony Turnage opera excursion heads down a mistaken track

The Railway Children, Glyndebourne review - right train, wrong station

Talent-loaded Mark-Anthony Turnage opera excursion heads down a mistaken track

La bohème, Opera North review - still young at 32

Love and separation, ecstasy and heartbreak, in masterfully updated Puccini

La bohème, Opera North review - still young at 32

Love and separation, ecstasy and heartbreak, in masterfully updated Puccini

Albert Herring, English National Opera review - a great comedy with depths fully realised

Britten’s delight was never made for the Coliseum, but it works on its first outing there

Albert Herring, English National Opera review - a great comedy with depths fully realised

Britten’s delight was never made for the Coliseum, but it works on its first outing there

Carmen, English National Opera review - not quite dangerous

Hopes for Niamh O’Sullivan only partly fulfilled, though much good singing throughout

Carmen, English National Opera review - not quite dangerous

Hopes for Niamh O’Sullivan only partly fulfilled, though much good singing throughout

Giustino, Linbury Theatre review - a stylish account of a slight opera

Gods, mortals and monsters do battle in Handel's charming drama

Giustino, Linbury Theatre review - a stylish account of a slight opera

Gods, mortals and monsters do battle in Handel's charming drama

Susanna, Opera North review - hybrid staging of a Handel oratorio

Dance and signing complement outstanding singing in a story of virtue rewarded

Susanna, Opera North review - hybrid staging of a Handel oratorio

Dance and signing complement outstanding singing in a story of virtue rewarded

Ariodante, Opéra Garnier, Paris review - a blast of Baroque beauty

A near-perfect night at the opera

Ariodante, Opéra Garnier, Paris review - a blast of Baroque beauty

A near-perfect night at the opera

Cinderella/La Cenerentola, English National Opera review - the truth behind the tinsel

Appealing performances cut through hyperactive stagecraft

Cinderella/La Cenerentola, English National Opera review - the truth behind the tinsel

Appealing performances cut through hyperactive stagecraft

Add comment