Venice Biennale 2022 review - The Milk of Dreams Part 2: The Arsenale | reviews, news & interviews

Venice Biennale 2022 review - The Milk of Dreams Part 2: The Arsenale

Venice Biennale 2022 review - The Milk of Dreams Part 2: The Arsenale

This wildly ambitious mega-exhibition unravels in spectacular style

Part two of The Milk of Dreams, the central International Exhibition at the 2022 Venice Biennale, housed in the Arsenale shipyard, starts with the kind of massive, grandstanding gesture that’s necessary in a venue of this scale: a colossal bronze bust of a Black woman by American artist Simone Leigh.

It’s a powerful image with which to open the second part of this massive and – wildly ambitious – exhibition, curated by the New York-based Italian Cecilia Alemani, which aims for nothing less than a new agenda for art. Focussing on the transformative power of the imagination, it explores the “interrelationship of species” – animal, vegetable and digital – and “posthuman” alternatives to the man-centred worldview that has done so much, it argues, to damage the planet.

If the eyelessness of Leigh’s figure isn’t explained in the accompanying wall-text, when you’re in an exhibition of this size – and the Arsenale’s massive halls stretch ahead of us for nearly half a mile – you haven’t the time or mental space for factual nit-picking. You need another gobsmacking work in short order to keep you on track, which is provided by a set of gigantic clay vessels in quasi-animal form by Argentinian artist Gabriel Chaile – only the second male artist we’ve encountered in this epic exhibition so far (pictured below, Gabriel Chaile's Mama Luchona, 2021). They’re actually “sculpture ovens”, works of art for creating more works of art. And with the largest standing a good 20 feet high, its neck extending ceiling-ward like a great chimney, they’re works on the kind of awe-inspiring scale that any exhibition in this massive venue has to keep providing to maintain momentum and avoid getting absolutely lost through the immense length of these galleries.

While The Milk of Dreams makes a few attempts at maintaining that sense of scale and structure it nonetheless proceeds to get pretty much completely lost.

While The Milk of Dreams makes a few attempts at maintaining that sense of scale and structure it nonetheless proceeds to get pretty much completely lost.

There are too many multi-screen films with humans in states of existential engagement with landscape, and whether we’re in a Norwegian pine forest, a Vietnamese rice field or Lithuanian sand dunes, the mood and feel tend to be monotonously similar. And there’s a great deal of folk-derived art, on the grounds, presumably, that people in “traditional” societies have a more honest and sustainable relationship both with nature and their dreams.

Zimbabwean artist Portia Zvavahera’s haunting large scale canvases create a sophisticated and genuinely innovative response to dream imagery rooted in both traditional Zimbabwean and Pentecostal Christian belief. Too much of the other painting here, though, succumbs to a generic folksy prettiness, whether it’s Eritrean artist Ficre Ghebreyesus’s densely coloured map-like compositions or Roberto Gil de Montes’s homoerotic responses to traditional Mexican folk painting, that stray too close for comfort towards touristic kitsch.

By a third of the way into this leg of the show I felt I’d scream if I saw another figure sprouting flames or plant-like capillary tendrils from its head or breasts or limbs. Probably there are only a handful of such works – Mexico’s Felipe Baeza and Brazil’s Rosana Paulino being notable offenders – but even, say, three feels far too many.

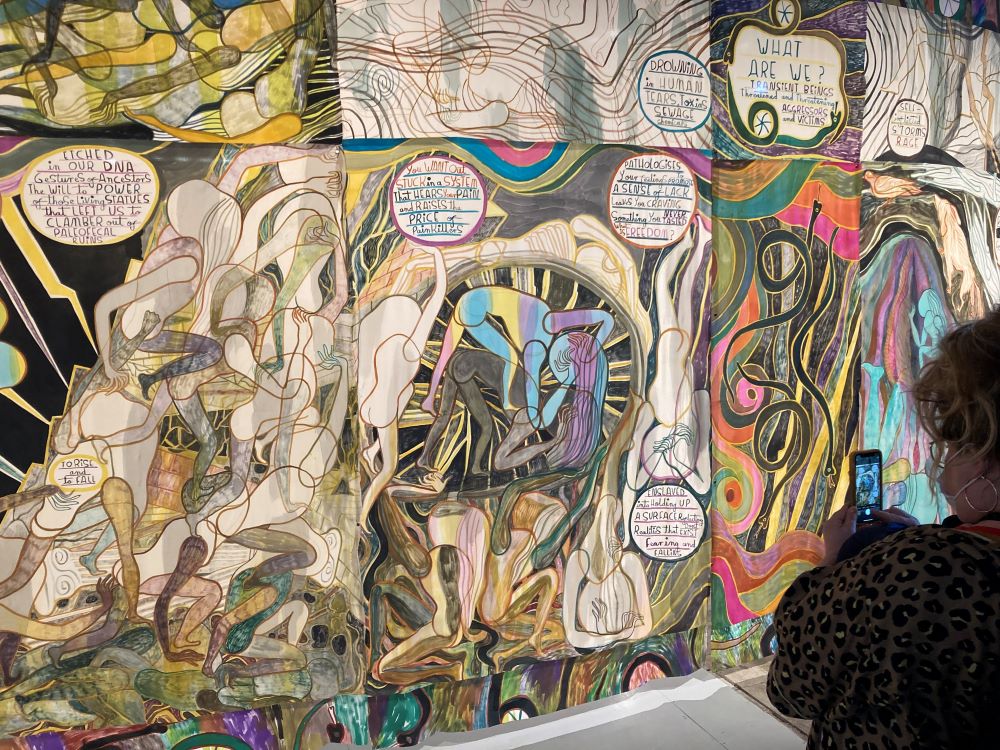

From the folk-derived, the faux-folk and the fake folk we jump to the supra-urban, post-modern folk art of Emma Talbot, winner of this year’s Max Mara Art Prize for Women, and one of the very few British artists included in this mammoth exhibition. Her vast silk banner, Where Do We Come From, What Are We, Where Are We Going (Pictured above, Emma Talbot's Where Do We Come From?, 2021), takes on Gauguin’s epic painting of the same title, critiquing the French painter’s urge for escape and a “return” to nature, in a neo-psychedelic, semenal flow of simplified human forms that splurges across this near-endless wraparound structure. It’s dotted with slogans voicing Talbot’s responses to those same urges: “You want out Stuck in a system that hears your pain and raises the price of painkillers.” On this showing the art of the future will be like something you’d encounter in a field in Wiltshire at an Extinction Rebellion-inspired festival only attended by people already convinced of the cause.

From the folk-derived, the faux-folk and the fake folk we jump to the supra-urban, post-modern folk art of Emma Talbot, winner of this year’s Max Mara Art Prize for Women, and one of the very few British artists included in this mammoth exhibition. Her vast silk banner, Where Do We Come From, What Are We, Where Are We Going (Pictured above, Emma Talbot's Where Do We Come From?, 2021), takes on Gauguin’s epic painting of the same title, critiquing the French painter’s urge for escape and a “return” to nature, in a neo-psychedelic, semenal flow of simplified human forms that splurges across this near-endless wraparound structure. It’s dotted with slogans voicing Talbot’s responses to those same urges: “You want out Stuck in a system that hears your pain and raises the price of painkillers.” On this showing the art of the future will be like something you’d encounter in a field in Wiltshire at an Extinction Rebellion-inspired festival only attended by people already convinced of the cause.

There’s a similar retro-utopian feel to Dominican-born American painter Firelei Baez’s wafting, candy coloured, Afro cosmic-fantasies, which bring a flavour of early Seventies jazz-rock album cover art. Chilean artist Sandra Vasquez de Hora’s immensely detailed, multi-layered and rather amazing pencil drawings of women’s bodies (Pictured right, work by Sandra Vasquez de Hora) look like examples of some long-lost Sixties feminist art, though they were all produced last year. The feel in this part of the show seems to be, “Hippiedom didn’t really work, but let’s give it another go anyway.”

There’s a similar retro-utopian feel to Dominican-born American painter Firelei Baez’s wafting, candy coloured, Afro cosmic-fantasies, which bring a flavour of early Seventies jazz-rock album cover art. Chilean artist Sandra Vasquez de Hora’s immensely detailed, multi-layered and rather amazing pencil drawings of women’s bodies (Pictured right, work by Sandra Vasquez de Hora) look like examples of some long-lost Sixties feminist art, though they were all produced last year. The feel in this part of the show seems to be, “Hippiedom didn’t really work, but let’s give it another go anyway.”

Works by German artist Raphaela Vogel and Swiss painter Louise Bonnet disrupt the beatific mood. Vogel’s Ability and Necessity, a metre high anatomical model of set of diseased male genitals mounted on a trolley and pulled by six life-size giraffes realised in a sort of gluey plastic latticework looks like something Damien Hirst might have produced if he’d been a militant feminist. Bonnet’s Pisser Triptych acts as a kind of enormous altarpiece to the bodily functions, with galumphing figures farting and exhaling air through their breasts.

But the work that most startles in this part of the exhibition – and each of the enormous rooms feels like an exhibition in its own right – are Polish artist Joanna Piotrowska’s carefully staged domestic scenes with postures drawn from self-defence manuals. It’s not so much the dramatic content that brings you up short as the gritty ordinariness of the black and white photography. I had the same reaction with the china and steel sinks in American artist Carolyn Lazard’s installation on the “temporality of illness and work of care”. Never mind the highfalutin rhetoric: after a surfeit of milky, magical dreaminess I felt like embracing these objects for their sheer blank mundanity.

There’s some great work in this exhibition. Lebanese artist Ali Cherri’s monumental fake antiquities formed from the mud surrounding actual ancient objects offer a witty and visually powerful play on the processes of archaeology. Canadian artist Tau Lewis’s gigantic cat faces with disconcertingly human lips and noses, hand stitched from scraps of textile and fake fur, are downright hilarious.

Yet these works get somewhat lost amid a prevailing conception of the imagination that focuses almost exclusively on the visionary and the fantastic. The Milk of Dreams is being hailed as the return of surrealism. But where the original surrealism drew much of its impact from the disjunction of the absurd and the everyday, Alemani’s nouveau surrealiste/faux-folk/sci-fi mash-up seems to be taking place in a parallel reality where politics, work and most of the other stuff that takes up most of our time don’t exist. This is a show composed 95% of art by women, that barely reference the unbelievable exploitation and abuse still suffered by women everywhere in the world. That isn’t a problem in itself: not all art can or should be social realism. But too much of the work here has the callow, cosmetic feel of art that only exists to be put in art galleries.

This is particularly evident in one of the sections of the show that’s garnered most attention, focussing on futuristic “posthuman” visions of “human/non-human interaction” and “technology’s annexation of the human body”. Particularly prominent is the notion of the “cyborg”, a conjectural future-being with implanted technologies and human, machine and animal attributes. While the notion was originally devised by scientists to describe a possible actual reality, it was rapidly commandeered by science fiction and science fantasy writers – and so the idea is played out in this exhibition.

While Alemani rightly claims that the “boundaries between bodies and objects have been utterly transformed” by technology, there’s no hint in the art here of the sensual and tactile level on which the notion of the “cyborg” is already being played out in daily life. Everything seems conceived on the level of fantastic spectacle.

Korean artist Mire Lee’s continually shifting, dripping, animatronic faux-organisms – to take one of the more compelling examples – suggest great clusters of human or animal innards suspended on a giant frame. They are in fact polyester tubes leaking engine grease, silicone and liquid clay, and while they evoke a just about convincing fusion of organic and machine elements, it’s not clear where further we’re supposed to take that idea.

French artist Marguerite Humeau’s technically extraordinary large-scale sculptures evoke a multiplicity of organic forms and textures that it’s hard to quite put your finger on (Pictured above, Marguerite Humeau's Migrations 2022). There are simultaneous suggestions of drifting underwater vegetation, dessicated bones and distant lunar landscapes. These forms seem to hang weightless in space despite being realised in all too material polyurethane and fibreglass. Yet for all their rich biomorphic associations, the reality they embody feels to me entirely digital: the hyperreal unreality of the landscapes in video games. Like much of the work here Humeau’s work feels imbued with a generational sensibility that’s informed as much by fantasy in the form of gaming, super hero franchise movies and manga as it is by post-modern critical theory. I wouldn’t have been surprised to see Harry Potter come walking round the corner.

French artist Marguerite Humeau’s technically extraordinary large-scale sculptures evoke a multiplicity of organic forms and textures that it’s hard to quite put your finger on (Pictured above, Marguerite Humeau's Migrations 2022). There are simultaneous suggestions of drifting underwater vegetation, dessicated bones and distant lunar landscapes. These forms seem to hang weightless in space despite being realised in all too material polyurethane and fibreglass. Yet for all their rich biomorphic associations, the reality they embody feels to me entirely digital: the hyperreal unreality of the landscapes in video games. Like much of the work here Humeau’s work feels imbued with a generational sensibility that’s informed as much by fantasy in the form of gaming, super hero franchise movies and manga as it is by post-modern critical theory. I wouldn’t have been surprised to see Harry Potter come walking round the corner.

The posthuman as presented here feels like an intellectual posture that is too often simply illustrated on a decorative level – Russian Zhenya Machneva’s tapestries – or approached through a generic sci-fi aesthetic that feels spiritually rooted in the mid-20th century. American sculptor Tishan Hsu’s “architectonic”, cyborgian objects make seductive and undeniably innovative use of ultra-modern materials and processes. Yet they kept taking me back to Stanley Kubrick’s 1968 film 2001: A Space Odyssey.

The fact that this massively women-dominated exhibition doesn't set out to provide a survey of "women's art" makes it all the more effective as a demonstration of the limitless variety of the art poroduced by women today.

As a piece of exhibition-making – an exercise in structuring a massive amount of art through two colossal venues – this is the least successful of the last three Biennale shows. Catherine Macel’s Viva Arte Viva in 2017 and Ralph Rugoff’s May You Live In Interesting Times in 2019, both paced themselves to deliver the climactic moments that would hold the attention through these vast spaces. Yet if The Milk of Dreams feels meandering and hastily assembled at times, Cecilia Alemani has provided something those earlier exhibitions lacked: a really provocative premise that gets you thinking and lingers in the mind long after you’ve left. Even at its most exasperating, this exhibition is never less than stimulating – even if it did leave me a touch dispirited about the future of art. If art is intrinsic to human existence, one of the best ways to embrace the posthuman is surely to stop making art altogether.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Comments

THE MILK OF NIGHTMARES... or