Who On Earth Was Ford Madox Ford?, BBC Two | reviews, news & interviews

Who On Earth Was Ford Madox Ford?, BBC Two

Who On Earth Was Ford Madox Ford?, BBC Two

The lively story of the author of Parade's End is revisited

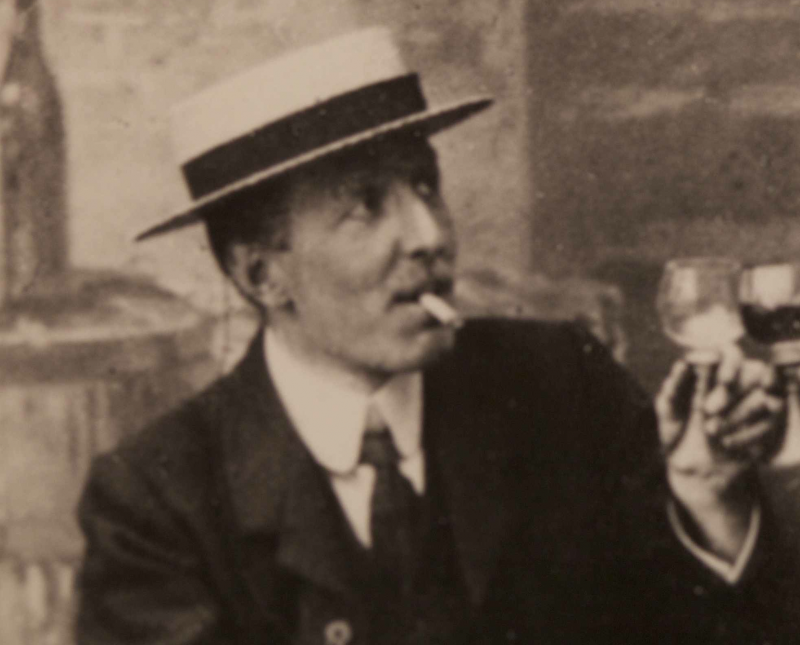

The verdict may still be out on the BBC’s lavish unfolding drama, Parade’s End, but it’s already done one thing: to bring the name of its writer, Ford Madox Ford, back from the (relative) oblivion where it has been since his death in 1939 (not least thanks to a script from Tom Stoppard).

In 1919, the writer changed his name from its German-sounding original, Ford Madox Hueffer, choosing his new moniker after his maternal grandfather, the Pre-Raphaelite painter Ford Madox Brown. That sense of "association" seems typical for him as an individual: Ford was on the edge of the most eminent intellectual company of his generation - a list of names of those with whom he worked as editor and publisher, first at the pre-World War I The English Review, and post-war at The Transatlantic Review, reads like a roll-call of 20th-century literature in the English language. His closest literary collaborator (they wrote novels together) may have been Joseph Conrad, but HG Wells, Thomas Hardy, DH Lawrence and Henry James all feature in his story, as from a later Paris decade do Ernest Hemingway, and the giants of modernism, Ezra Pound, James Joyce and Wyndham Lewis.

His emotional life was turbulent, with at least five relationships with variously wives or lovers

His emotional life was turbulent, with at least five relationships with women charted here, variously wives or lovers. Periodic relocations found him in parts of the English countryside (gloriously caught in rather lonely visuals in the programme), through spa-town pre-World War I Germany (the setting for The Good Soldier), doing short and unlikely military service on the Somme, then in Paris, Provence and New York, to name only a few of his peregrinations. Yentob made it to all of them, and told the story from director Rupert Edwards without over-intrusion into its narrative (disclaimer here: this reviewer collaborated previously with both on the Imagine film The Trouble with Tolstoy).

The archive footage really struck, too, collected from everywhere that featured in Ford’s life, most notably the Somme, surely the crucial experience that changed the perceptions of his generation from how life was before, to how it would be after. Simon Russell Beale voiced Ford’s words with empathy. John Simpson spoke very perceptively about Ford’s self-deprecating and even self-saboteuring personality (and the escape from emotional tribulations that saw him enlist, despite being old enough - and portly enough - to have avoided it).

Ford had to write prolifically for a living, producing a huge number of books, not unlike his contemporary, Edward Thomas, for the money. He achieved affluence only later in life (and even then a very sizable wodge of cash blew away by mistake into a French river). He also wrote about food, and one sensed here a rich, even gluttonous strand typical of his times. Chef Rowley Leigh recreated a “lenten meal” following the writer’s instructions which seemed far from “austere”, as Ford termed it.

Hermione Lee described Ford as “consumed with the idea of love”, and his five serial life-partners defined the story. Childhood sweetheart Elsie, who eloped with him from her disapproving parents, and married him by forging their ages, was followed by novelist and literary socialite Violet Hunt, a troubled relationship that he escaped to go to war. After he was invalided out, there was Australian painter Stella Bowen, who gave birth to his daughter, the only child alluded to in the film (it would have been interesting to have learnt more of her fate). Number four was Jean Rhys who, like so many others Ford advised on her writing, and who in turn depicted him, far from flatteringly, in her novel Quartet. His final partner was American painter Janice Biala, with whom he spent the last years of his life between America and France - his grandfather Ford Madox Brown's The Last of England (pictured above right) was used to illustrate Ford's own emigration. He died in Deauville in June 1939, less than three months before another war would convulse the continent.

Hermione Lee described Ford as “consumed with the idea of love”, and his five serial life-partners defined the story. Childhood sweetheart Elsie, who eloped with him from her disapproving parents, and married him by forging their ages, was followed by novelist and literary socialite Violet Hunt, a troubled relationship that he escaped to go to war. After he was invalided out, there was Australian painter Stella Bowen, who gave birth to his daughter, the only child alluded to in the film (it would have been interesting to have learnt more of her fate). Number four was Jean Rhys who, like so many others Ford advised on her writing, and who in turn depicted him, far from flatteringly, in her novel Quartet. His final partner was American painter Janice Biala, with whom he spent the last years of his life between America and France - his grandfather Ford Madox Brown's The Last of England (pictured above right) was used to illustrate Ford's own emigration. He died in Deauville in June 1939, less than three months before another war would convulse the continent.

You could say that Ford is more of a writer’s writer, but the popular success of Parade’s End in America was dramatically greater than in his homeland, and he remains an ongoing subject of academic study there. “No novelist of this century is more likely to live,” Graham Greene would write in tribute. Who On Earth Was Ford Madox Ford? made a good case for reviving interest not only in his life, but also in his work, and reinstating him into the pantheon of writers of his generation.

Explore topics

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more TV

theartsdesk Q&A: writer and actor Mark Gatiss on 'Bookish'

The multi-talented performer ponders storytelling, crime and retiring to run a bookshop

theartsdesk Q&A: writer and actor Mark Gatiss on 'Bookish'

The multi-talented performer ponders storytelling, crime and retiring to run a bookshop

Ballard, Prime Video review - there's something rotten in the LAPD

Persuasive dramatisation of Michael Connelly's female detective

Ballard, Prime Video review - there's something rotten in the LAPD

Persuasive dramatisation of Michael Connelly's female detective

Bookish, U&Alibi review - sleuthing and skulduggery in a bomb-battered London

Mark Gatiss's crime drama mixes period atmosphere with crafty clues

Bookish, U&Alibi review - sleuthing and skulduggery in a bomb-battered London

Mark Gatiss's crime drama mixes period atmosphere with crafty clues

Too Much, Netflix - a romcom that's oversexed, and over here

Lena Dunham's new series presents an England it's often hard to recognise

Too Much, Netflix - a romcom that's oversexed, and over here

Lena Dunham's new series presents an England it's often hard to recognise

Insomnia, Channel 5 review - a chronicle of deaths foretold

Sarah Pinborough's psychological thriller is cluttered but compelling

Insomnia, Channel 5 review - a chronicle of deaths foretold

Sarah Pinborough's psychological thriller is cluttered but compelling

Live Aid at 40: When Rock'n'Roll Took on the World, BBC Two review - how Bob Geldof led pop's battle against Ethiopian famine

When wackily-dressed pop stars banded together to give a little help to the helpless

Live Aid at 40: When Rock'n'Roll Took on the World, BBC Two review - how Bob Geldof led pop's battle against Ethiopian famine

When wackily-dressed pop stars banded together to give a little help to the helpless

Hill, Sky Documentaries review - how Damon Hill battled his demons

Alex Holmes's film is both documentary and psychological portrait

Hill, Sky Documentaries review - how Damon Hill battled his demons

Alex Holmes's film is both documentary and psychological portrait

Outrageous, U&Drama review - skilfully-executed depiction of the notorious Mitford sisters

A crack cast, clever script and smart direction serve this story well

Outrageous, U&Drama review - skilfully-executed depiction of the notorious Mitford sisters

A crack cast, clever script and smart direction serve this story well

Prost, BBC 4 review - life and times of the driver they called 'The Professor'

Alain Prost liked being world champion so much he did it four times

Prost, BBC 4 review - life and times of the driver they called 'The Professor'

Alain Prost liked being world champion so much he did it four times

The Buccaneers, Apple TV+, Season 2 review - American adventuresses run riot in Cornwall

Second helping of frothy Edith Wharton adaptation

The Buccaneers, Apple TV+, Season 2 review - American adventuresses run riot in Cornwall

Second helping of frothy Edith Wharton adaptation

The Gold, Series 2, BBC One review - back on the trail of the Brink's-Mat bandits

Following the money to the Isle of Man, Spain and the Caribbean

The Gold, Series 2, BBC One review - back on the trail of the Brink's-Mat bandits

Following the money to the Isle of Man, Spain and the Caribbean

Dept. Q, Netflix review - Danish crime thriller finds a new home in Edinburgh

Matthew Goode stars as antisocial detective Carl Morck

Dept. Q, Netflix review - Danish crime thriller finds a new home in Edinburgh

Matthew Goode stars as antisocial detective Carl Morck

Comments

Does anybody know which music

I enjoyed the show but agree