Opinion: Is acting now just for the privileged? | reviews, news & interviews

Opinion: Is acting now just for the privileged?

Opinion: Is acting now just for the privileged?

How the dramatic arts are reacting to the Etonian insurgency

Knock knock. Who's there? Eamonn. Eamonn who? Eamonn Etonian. There's an Eamonn at No 10, an Eamonn is Mayor of London, an Eamonn is even Archbishop of Canterbury. Oh, and Eamonns are third and - for three more months - fourth in line to the throne. Recently Eton has started to dominate British film, television and theatre. In 2012 one Eamonn won an Emmy, another was given a Bafta and a third played a Shakespearean king on the BBC.

It’s true that a remarkably talented group of actors from Eton have risen like the richest cream to the top in recent years. They are led by Damian Lewis, star of Homeland, and Dominic West of The Wire, and a slightly younger crop including Tom Hiddleston, star of the BBC’s Henry V and War Horse, and Eddie Redmayne, who played the male lead in the BBC’s Birdsong and My Week with Marilyn. Other public schools are helping to keep it real in the costume dramas. The two leads actors in Parade’s End (pictured below right) went to the best schools: Benedict Cumberbatch (also the BBC's current Sherlock Holmes) to Harrow, Rebecca Hall to Roedean. Downton’s Earl of Grantham, Hugh Bonneville, was educated at Sherborne and his (now late) heir was played by Dan Stevens, who was schooled at Tonbridge. The National's latest Iago Rory Kinnear went to St Paul's. And so on and on.

Naturally this causes consternation in the expected places. “It is sad that so many of the young leading actors are coming from such a narrow social background,” says Ken Loach, the veteran director. “I’m sure they are very proper and decent and reasonable people. I can’t blame a lad who has gone to a school at his parents’ choice. But it emphasises the fact that this is a society based on class and that privilege confers status.”

Naturally this causes consternation in the expected places. “It is sad that so many of the young leading actors are coming from such a narrow social background,” says Ken Loach, the veteran director. “I’m sure they are very proper and decent and reasonable people. I can’t blame a lad who has gone to a school at his parents’ choice. But it emphasises the fact that this is a society based on class and that privilege confers status.”

The actors in question are understandably loath to talk about their schooling in interviews – Cumberbatch has even contemplated moving to the less class-obsessed US where people will stop asking him about it. “It’s fairly shallow label just like any label,” says Dominic West, whose very un-Etonian performances include Fred West in Appropriate Adult (pictured below), for which he won a Bafta. “I think I’ve done enough in my career to show that I shouldn’t be entirely employed as a posh guy in a costume drama.”

“It comes with a set of assumptions which you don’t necessarily want to be associated with,” says Tom Hiddleston. “It’s a very easy pigeonhole. Box: Etonian. And whatever set of pigheaded misogynistic braying toff assumptions that that comes with that you’ll be somehow inept but extremely confident, borderline arrogant. And the likelihood is you go hunting, shooting and fishing every weekend. I just find it so exhausting and one doesn’t just want to be limited by those associations.”

There’s not much point in penalising the talented on the grounds that their parents spent a lot of money on their education. What is worth pondering, however, is whether opportunities are now unfairly tilted in favour of young actors from wealthy backgrounds. That certainly seems to be the perception among some of the profession’s senior voices. Last autumn as the fresh intake of aspiring thespians began paying £9,000 a year in tuition fees, Julie Walters suggested to the Sunday Times that in such a climate she would never have become an actress. “It was still possible for a working-class kid like me to study drama,” she said, “because I got a grant. But the way things are now, there aren’t going to be any working-class actors. I look at almost all the up-and-coming names and they’re from the posh schools.”

There’s not much point in penalising the talented on the grounds that their parents spent a lot of money on their education. What is worth pondering, however, is whether opportunities are now unfairly tilted in favour of young actors from wealthy backgrounds. That certainly seems to be the perception among some of the profession’s senior voices. Last autumn as the fresh intake of aspiring thespians began paying £9,000 a year in tuition fees, Julie Walters suggested to the Sunday Times that in such a climate she would never have become an actress. “It was still possible for a working-class kid like me to study drama,” she said, “because I got a grant. But the way things are now, there aren’t going to be any working-class actors. I look at almost all the up-and-coming names and they’re from the posh schools.”

Brian Cox, who joined Dundee Rep at 14, has also voiced concern in the Sunday Telegraph that “young people don’t have the opportunities that I had. That understanding of the need for social mobility that came after the Second World War has gone. It’s like we’ve excluded a root element from cultural life and I think that’s very dangerous. I think the acting industry should be more mixed. At the moment, it’s cutting itself off from a whole section of society.”

Heeding these warnings, the actress Clare Higgins last September revealed that she is working with other actors to launch a free drama school for young people who cannot afford the tuition fees for drama school. “We can’t go on with this any longer where only rich people can afford to train in the arts,” she told The Stage, “so we have to get out there and make it change now.”

And then this week Dominic Dromgoole, artistic director of Shakespeare’s Globe, announced that the theatre would be forming a new child company of 16 or so actors aged between 12 and 16, selected from “a broad social spectrum”. “It’s becoming harder and harder for children and young actors without means to get into drama school,” he said at the season launch this week of the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse, the Globe’s new indoor studio space. “I think that’s an enormous shame. I think that the actors coming through are immensely talented. I don’t want to say the young actors aren’t great; they’re terrific. But a thinning of the social spectrum is a real concern and a real worry.”

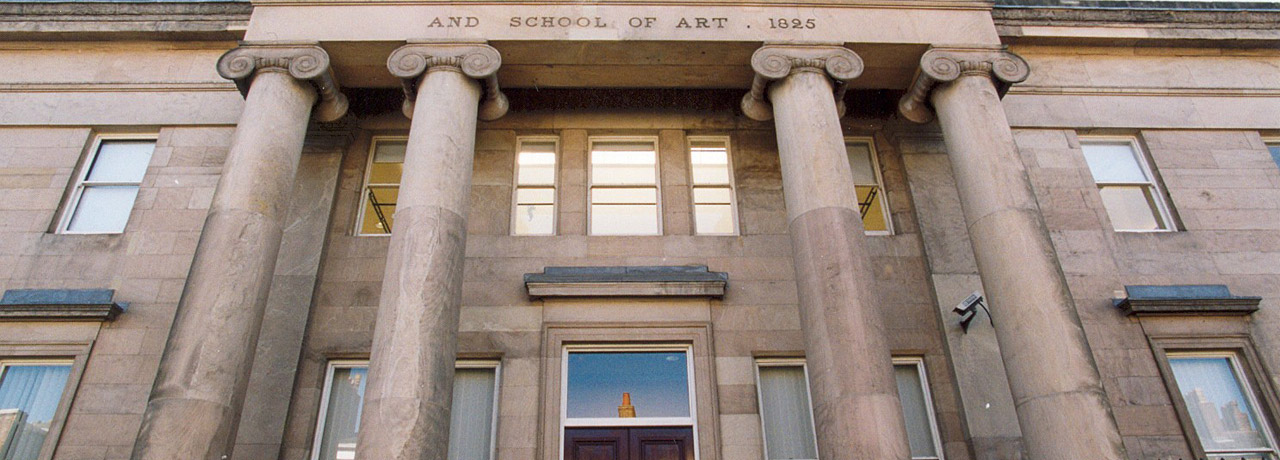

But aside from the furore focused on a few privately educated stars, what do the regular drama schools have to say about all this? It’s certainly true that £9,000 is a sizeable loan to be saddled with after three years of training to enter a hugely precarious and, for the most part, poorly remunerated profession. But not everyone in the industry supports the view that opportunities for actors from lower-income families have shrunk. “The funding of higher education has changed,” says Mark Featherstone-Witty, the founding principal and CEO of Liverpool Institute of Performing Arts (pictured above). “If a student’s family income falls below £21,000 you get everything for free. It’s a wonderful deal for actors from any background. You have to earn £21,000 before you start paying the loan, and the chances of your earning £21,000 in a year are minimal.”

But aside from the furore focused on a few privately educated stars, what do the regular drama schools have to say about all this? It’s certainly true that £9,000 is a sizeable loan to be saddled with after three years of training to enter a hugely precarious and, for the most part, poorly remunerated profession. But not everyone in the industry supports the view that opportunities for actors from lower-income families have shrunk. “The funding of higher education has changed,” says Mark Featherstone-Witty, the founding principal and CEO of Liverpool Institute of Performing Arts (pictured above). “If a student’s family income falls below £21,000 you get everything for free. It’s a wonderful deal for actors from any background. You have to earn £21,000 before you start paying the loan, and the chances of your earning £21,000 in a year are minimal.”

The anxiety of those running drama schools is that this message has not reached the people it’s meant for. “My biggest fear is that the anecdotal perception will get out there,” says Edward Kemp, principal of RADA, “and people will stop applying from precisely those bits of the community that we’ve had such a success in getting into the profession. RADA’s intake [this year] looks very like the last two or three years but I don’t know how long that will carry on and we’re seriously worried about that.”

They have reason to be worried, suggests the actor David Morrissey, star of many television dramas including State of Play and The Deal and, in the US, The Walking Dead (pictured right). Morrissey was brought up in the Knotty Ash area of Liverpool. His father was a cobbler and his mother worked at Littlewoods. He failed the 11 plus and left school at 16 with no O-levels. But as an enthusiastic young actor, he was cast in Channel 4’s first ever drama series and decided to try for RADA.

They have reason to be worried, suggests the actor David Morrissey, star of many television dramas including State of Play and The Deal and, in the US, The Walking Dead (pictured right). Morrissey was brought up in the Knotty Ash area of Liverpool. His father was a cobbler and his mother worked at Littlewoods. He failed the 11 plus and left school at 16 with no O-levels. But as an enthusiastic young actor, he was cast in Channel 4’s first ever drama series and decided to try for RADA.

“I would have been loath to borrow money to go to drama school,” he says. “I think the figure of £9,000 would have put me off and I'm sure my family would have advised me against it. But I don't think anything would have stopped me trying my utmost to become an actor. Because acting and the arts in general are vocational, as a young person you are open to exploitation. You will work for nothing in order to get close to your dream and because of this you can be taken advantage of. And if you don't have any other forms of income, ie parents, then that door can be closed for you.”

Acting is unique among the performing arts in that expensive training is optional. For music and standup, none is required. For dance and classical music, it remains essential. But there is no official route into stage and screen acting. Loach, who has cast many non-professional actors in his films, points out that this route is a lottery. “Often people from an ordinary background can find a way in to films, but it’s entirely a matter of chance as to whether they fit a particular search at a particular time. It’s taken out of their hands, whereas applying to drama school is within their control.”

One of the reasons why standards are so high among privately educated actors is the seriousness with which public schools are nowadays treating the arts. Eton is notable but not remotely alone in supplying facilities for drama which are of professional standard. “It would be nice if those resources were available for the state schools,” says Featherstone-Witty, “but even performing arts academies don’t have those facilities.”

But facilities aren’t everything, says the director Christopher Luscombe. He was recently invited to Eton to give a workshop for the teaching staff about directing plays. “The quality of drama teaching at the school seems to be very high. They have a dedicated drama department, but also have a lot of other lively, very engaged staff who seem to be interested in the challenge of directing plays. And that’s producing very strong drama students which has led to high-profile young actors.”

But facilities aren’t everything, says the director Christopher Luscombe. He was recently invited to Eton to give a workshop for the teaching staff about directing plays. “The quality of drama teaching at the school seems to be very high. They have a dedicated drama department, but also have a lot of other lively, very engaged staff who seem to be interested in the challenge of directing plays. And that’s producing very strong drama students which has led to high-profile young actors.”

The irony is that the place which helped broaden the playing range of Hiddleston (pictured above left) and Morrissey alike is RADA. “Drama school was exceptionally important for me,” says Morrissey, whose application for RADA was successful. “It meant I could forge a career rather than get stuck in one type of role. I do have a real concern about how much it costs to go to drama school now. That is definitely something that will alienate lower-income families.”

“We are in year one of this,” says Edward Kemp of RADA. “The cliff we feared we were about to go over the edge of hasn’t appeared yet. We’ve still got substantial numbers applying. Nine grand doesn’t seem to have deterred people. But we won’t know. We are undertaking a big experiment. If the media is full of stories in seven or eight years’ time about actors on the breadline and crippled by debt, then we’ll know.”

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Comments

Fascinating, very fair and

Coming from a privileged

Julie & Dominic are

I should point out that the

Yes ! connections, nepotism,