Mangan, Royal Academy Opera Students, BBCSO, Denève, Barbican Hall | reviews, news & interviews

Mangan, Royal Academy Opera Students, BBCSO, Denève, Barbican Hall

Mangan, Royal Academy Opera Students, BBCSO, Denève, Barbican Hall

Hands on hearts for the sadness and profundity in two French fantasies

Highly sexed cockerels and cats, a lovesick lion and a ballet of frogs might not seem like a recipe, or rather a menagerie, for profundity. Yet in two ravishing French man (or child)-meets-beast fables for the stage, Poulenc and Ravel are quite capable of tearing at our heartstrings. That they did so unremittingly last night was very largely due to the supernaturally beautiful sounds master conjuror Stéphane Denève drew from the BBC Symphony Orchestra.

Yet more than just the icing on the cake was the collective and individual presence of students from the Royal Academy of Music for Ravel's L'enfant et les sortilèges. So at least three ages of man – children as young as two with their parents in the audience for this Family Concert, teenagers and twentysomethings onstage and off and the rest of us – played their part in a miraculous evening.

It might seem reductive to limit a musician to national specialities, but having heard Denève’s Berlioz, Debussy and Roussel in concert, his captivating disc of Poulenc with the Stuttgart orchestra he commands and now his Ravel, I can honestly say there’s no conductor alive I’d rather hear in French music. He pledged his faith in the unorthodox by starting with Poulenc’s suite from the 1940s ballet based on La Fontaine, Les animaux modèles.

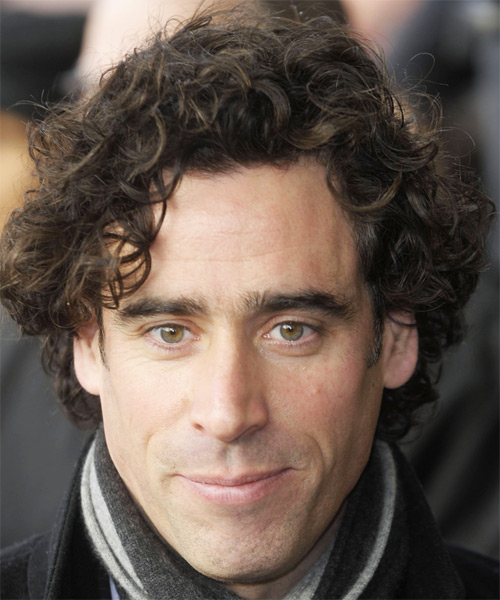

Only the 50th anniversary of the lovable Poulenc’s death could have coaxed two performances of this rarity out of its cage in less than a month. But where the City of London Sinfonia’s Southwark Cathedral rendition was lumpy and obscure, all was clear and buoyant here. It helped enormously that we had that quicksilver actor Stephen Mangan (pictured right) reading the La Fontaine fables in between numbers (in Southwark, most of us remained ignorant of their morals, and the programme offered no help).

Only the 50th anniversary of the lovable Poulenc’s death could have coaxed two performances of this rarity out of its cage in less than a month. But where the City of London Sinfonia’s Southwark Cathedral rendition was lumpy and obscure, all was clear and buoyant here. It helped enormously that we had that quicksilver actor Stephen Mangan (pictured right) reading the La Fontaine fables in between numbers (in Southwark, most of us remained ignorant of their morals, and the programme offered no help).

Sounding not one false note in a witty new translation by Craig Hill and never overdoing the funny voices, Mangan chilled us to the bone in the tale of the woodcutter tired of a life without light or joy who invites death. Denève, who had scattered brisk, sensuous stardust over his orchestra from the start, underlined Poulenc’s gravely beautiful Pas de deux with poised assistance from oboist Richard Simpson and perfectly gauged wind and brass ensembles. With Mangan delivering a final envoi of warning to victors – the Boches would of course have been in the Paris audience at the 1942 premiere – justice was done to the composer’s written insistence on the ballet’s moments of seriousness. Now we need to hear the whole thing, not just the suite.

Where Poulenc is poignant, Ravel breaks the heart. There’s so much more to his one-act operatic masterpiece than the tale of a naughty child who gets roughed up by the objects and animals he’s tormented, and learns a lesson. All that the composer had suffered serving in the First World War, all the losses – so many friends as well as, most significantly, the mother invoked in the opera – feed into the profound nostalgia and regret between the comic numbers. Denève and the many orchestral solos hit the right, exquisite note every time, especially in the piping pastoral of ripped wallpaper shepherds and shepherdesses, the solo flute (Michael Cox) that accompanies the picturebook princess (Sónia Grané, mesmerizing) and the floating violin line that drifts above, of all things, waltzing frogs. Is Ravel the master of all orchestrators? It seemed so here.

Where Poulenc is poignant, Ravel breaks the heart. There’s so much more to his one-act operatic masterpiece than the tale of a naughty child who gets roughed up by the objects and animals he’s tormented, and learns a lesson. All that the composer had suffered serving in the First World War, all the losses – so many friends as well as, most significantly, the mother invoked in the opera – feed into the profound nostalgia and regret between the comic numbers. Denève and the many orchestral solos hit the right, exquisite note every time, especially in the piping pastoral of ripped wallpaper shepherds and shepherdesses, the solo flute (Michael Cox) that accompanies the picturebook princess (Sónia Grané, mesmerizing) and the floating violin line that drifts above, of all things, waltzing frogs. Is Ravel the master of all orchestrators? It seemed so here.

Yet what made this performance unique, in my experience, was not so much the serviceable film and video sequences by Jean-Baptiste Barrière (pictured above at Montreal in 2007), simple enough to keep children posted of which character sings what, as the participation of the RAM students. The uniformly fine soloists seemed to know Colette's enchanting French text from the inside, led by Rozanna Madylus’s impetuous and touching Child. Better still, I wonder if Ravel’s choruses have ever been more glowingly and subtly served than by the ensemble from which the individual singers stepped out. The animals’ final fugal salute to a "good boy" could only leave us drifting out of the hall speechless, hands pointing to hearts. Perfection.

- Recorded for broadcast on BBC Radio 3 on 14 July

- Denève's Poulenc recording with his Stuttgart orchestra considered on David Nice's blog

rating

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Comments

I entirely agree with this