Duke Bluebeard's Castle, Philharmonia Orchestra, Salonen, Royal Festival Hall | reviews, news & interviews

Duke Bluebeard's Castle, Philharmonia Orchestra, Salonen, Royal Festival Hall

Duke Bluebeard's Castle, Philharmonia Orchestra, Salonen, Royal Festival Hall

Tomlinson and DeYoung render choreography for Bartók's opera superfluous

Sometimes the most disturbing images exist only in our imaginations - and so the questions posed in the preface to Bartók’s operatic masterpiece Duke Bluebeard’s Castle become especially pertinent: “Where did this happen - outside or within? Where is the stage - outside or within?” The answers, surely, lie “within”, making the prospect of a “semi-staged” climax to Esa-Pekka Salonen’s Philharmonia Bartók series, Infernal Dance, a potentially troubling one.

There was a “set” - a grey-walled shell and a pendulous shard-like mobile whose mere presence had one fearing the worst. And so the first half of the concert was played out within the environs of Bluebeard’s domain, as it were, with Debussy’s languorous faune stretched out in what remained of the afternoon sun. Odd auditory reflections from the Bluebeard set threw the textures into sharper relief, rather too brightly lit for the softer edges of the music to work their magic. There was nothing vague about the impressionism here. Samuel Coles’ gleaming solo flute had 20/20 vision.

Tomlinson’s cavernous voice seemed to embody the very interior world of his castle - its sadness, darkness, emptiness

And then the start of the evening’s Bartók: the home-away-from-home Third Piano Concerto with Yefim Bronfman, a sometime Bluebeard of the keys, robbing the piece of its highly personalised identity. His playing displayed all the lyricism of the abstracted set around him with the beauty of those tender Baroque allusions (the earthy acquiring airs) rendered sternly anonymous. At one point in the piece a scary spasm in the stage lighting came upon us like some divine intervention threatening to plunge us prematurely into the stygian gloom of the Duke’s castle. Or was it a certain lack of electricity in Bronfman’s playing?

And so, out of the post-interval darkness came Juliet Stevenson pronouncing that “the curtain of (our) eyelids” be raised revealing… what exactly? Is this piece stageable in any shape or form? Does movement or indeed any visual information add anything at all? Isn’t this the theatre of psychology, the dark heart of human desire? Nick Hillel (director), David Edwards and David Holmes (staging and lighting design) projected, in every sense, a series of unremarkable images – condensation running down cold surfaces, blood seeping through pierced cloth – but words and music unlock our collective imaginations here and our deepest fears produce the most unsettling images. We don’t need to see anything.

But we need to hear – undistracted – and what we were hearing was a quite superb and highly strung exposition of Bartók’s miraculous score from Salonen and the Philharmonia. That score imagines what lies behind each of the doors of Bluebeard’s psyche with such precise and extraordinary orchestral colorations that seeing somehow impedes hearing and inhibits imagination. As to the physical, the merest suggestion of a look or a touch or (surely never) an embrace between Judith and Bluebeard is too much information. Their presence must remain as intangible as the rasping sighs which emanate from the castle walls.

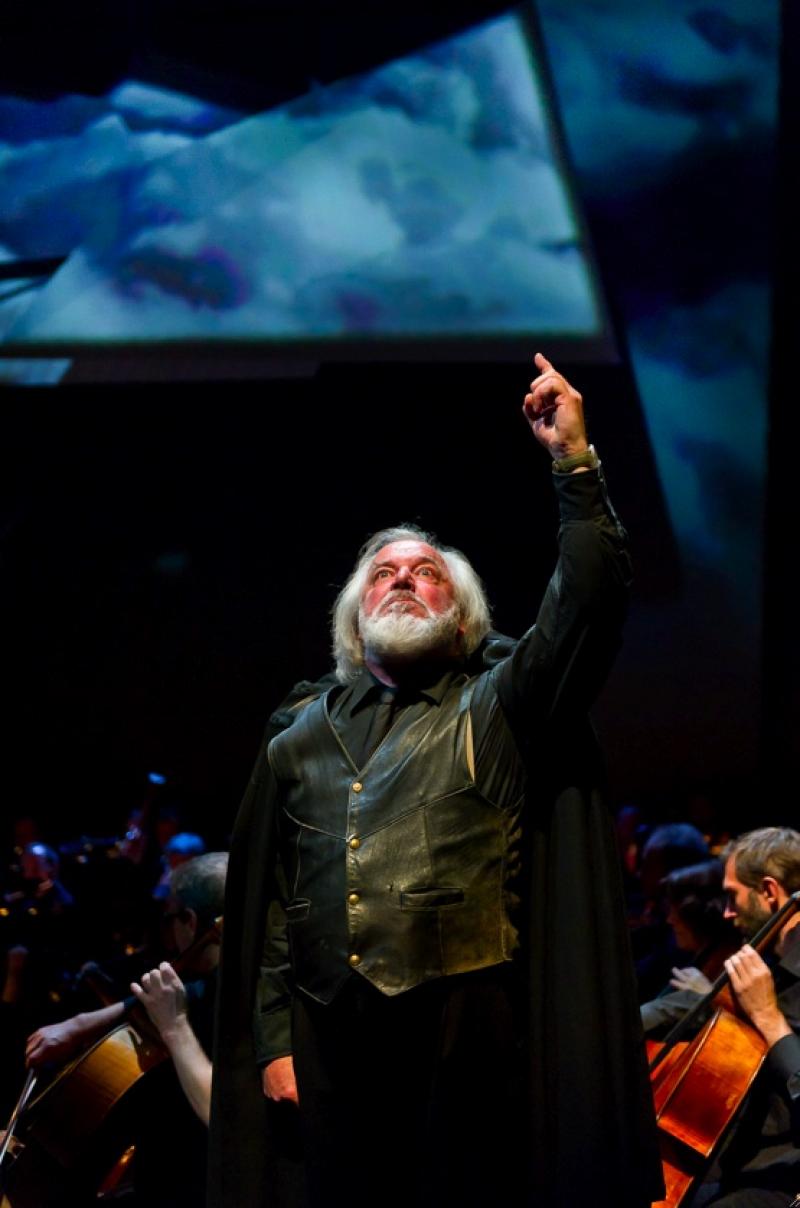

John Tomlinson and Michelle DeYoung were vocally so commanding as to render “choreography” entirely superfluous. Tomlinson’s cavernous voice seemed to embody the very interior world of his castle - its sadness, darkness, emptiness - his Hungarian so vivid and expressive in itself that it became another sonority in Bartók's aural palette. He was quite extraordinary.

Musically stunning, then - and how paradoxical that the single most sensational moment in the piece - the opening of the fifth door onto Bluebeard’s domains - should quite literally have blinded us from seeing anything.

- Check out the rest of the Philharmonia Orchestra's 2011-12 season

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Comments

I thought Bluebeard,

Helveticus You are

Absolutely agree with all of

The 'sighing' is specified in

Yes I realise the sigh is in