Richard Goode, Royal Festival Hall | reviews, news & interviews

Richard Goode, Royal Festival Hall

Richard Goode, Royal Festival Hall

The American master pianist's recital casts rewarding light on chewy repertoire

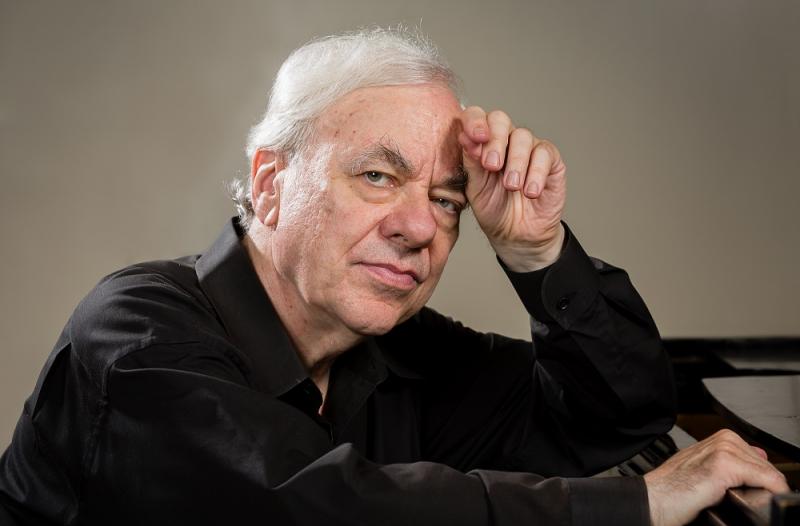

With Goode, a recital is all about the music (that might sound like stating the obvious, but one can’t guarantee it with every pianist these days). The veteran American has an unassuming stage presence, taking to the piano as if sitting down to demonstrate a musical point to friends in his living room. There is nothing flamboyant in his manner, nor in his musical concepts: simply the sense that he has lived with this music for decades and is pleased to play it for us. He uses a well-thumbed score and a page-turner; no Lisztian feats of memory, and no iPad. The magic is in the tone itself.

Goode’s Bach flows beautifully, with tempi that never rush yet do not make heavy weather of what can be an extremely chewy partita – it has, for instance, possibly the weirdest Gigue ever to bear that title, one that has more than a little in common with Beethoven's Grosse Fuge. He uses a discreet dash of pedal to provide resonance and just the right amount of colour – those who gasp in horror at pedalled Bach could reflect that the harpsichord has a natural resonance and no dampers. Goode makes sure that each dance has its own character, with contrasts and dynamics that are never too little and never too much.

Goode, thank goodness, is not a pianist who sends you home with your ears ringing

The late B major Nocturne Op. 62 No. 1 to start the Chopin group demonstrated the long perspective that made this such a clever programme. The Bach E minor Partita’s opening Toccata begins with a section full of upward flourishes. This Nocturne, too, opens with an upward flourish; and that internal Bachian echo set us up to listening out for its intertwining inner voices. But there was freedom and twilit poetry to relish, too, in this gorgeous song without words, in which Chopin’s coup-de-theatre is to bring the theme back garlanded in shimmering trills. Goode followed it with three mazurkas, two drawn from Op.41 plus the more extended C sharp minor from Op.50: the Op.41s are brief and inspiring poems, the first earthy and whimsical, the second twisting its more ingratiating charm towards a conclusion that sounds a little like a musical box winding down to a standstill.

The C sharp minor, a more complex exploration – again, very contrapuntal – set the scene for the Polonaise-Fantaisie, that enigmatic late masterpiece that can be a hymn to a lost homeland or a Tolstoyan epic condensed into about ten intense minutes. Goode’s account seemed less Tolstoy, more Keats, with intimacy to the fore rather than grandeur; we hear Chopin’s meditation on Poland through his subtle insights, rather than being asked to identify with the pain of exile. The pianist's masterful sense of ebb and flow created the impression of a free-flowing improvisation in which each thought grew out of the last in sponteneous manner, again without exaggeration and deliciously free of artifice; he pointed up the gleaming harmonic sideshifts of the nocturnal central section as if creating them from thin air. Again, his tone is key to the poetic concept, always clear and eloquent, yet feeling soft and cushioned even at its most fulsome in the triumphant final pages. Goode, thank goodness, is not a pianist who sends you home with your ears ringing.

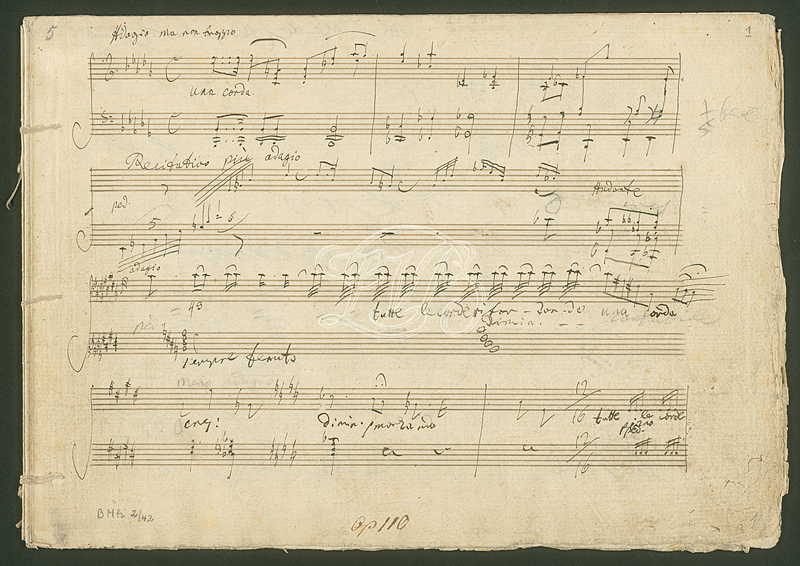

Late Beethoven, though, is Goode’s natural habitat and he brought us two of its fugue-rich treats, the A major Sonata Op.101 and the A flat major Op.110 (a page of Beethoven's sketches pictured above). It was here that another dimension seemed to come into play. Goode’s good humour and warmth shone through the energetic Op.101, with rock-solid rhythmic propulsion and considerable bounce. As for Op.110, theories abound about its “meaning” – extending to the idea that it is a love-song in some form to the Immortal Beloved who may or may not have been Josephine von Brunswick - but it really doesn’t need a meaning. We can divine that for ourselves in the other-worldly stardust that flows in waves through the first movement and, later, the pain-drenched Arioso and its exhausted return, each time regenerated by a giant fugue. If Goode’s ariosos sang convincingly, perhaps they kept us somewhat detached from the agony Beethoven can evoke here; but the fugues were the high point of the evening: the mysterious turning-upside-down was extraordinarily hushed and hypnotic, all the better as a launching pad into the blazing conclusion, which emerged palpably as one of the composer’s most glorious songs of thanksgiving, a paean of spiritual joy.

As encore, though, it was the world of the arioso, not that of the fugue, that Goode selected: a heart-rending sliver of Janáček’s On an Overgrown Path entitled, suitably enough, “Good Night”.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

Anja Mittermüller, Richard Fu, Wigmore Hall review - a glorious hall debut

The Austrian mezzo shines - at the age of 22

Anja Mittermüller, Richard Fu, Wigmore Hall review - a glorious hall debut

The Austrian mezzo shines - at the age of 22

First Person: clarinettist Oliver Pashley on the new horizons of The Hermes Experiment's latest album

Compositions by members of this unusual quartet feature for the first time

First Person: clarinettist Oliver Pashley on the new horizons of The Hermes Experiment's latest album

Compositions by members of this unusual quartet feature for the first time

Gesualdo Passione, Les Arts Florissants, Amala Dior Company, Barbican review - inspired collaboration excavates the music's humanity

At times it was like watching an anarchic religious procession

Gesualdo Passione, Les Arts Florissants, Amala Dior Company, Barbican review - inspired collaboration excavates the music's humanity

At times it was like watching an anarchic religious procession

Classical CDs: Camels, concrete and cabaret

An influential American composer's 90th birthday box, plus British piano concertos and a father-and-son duo

Classical CDs: Camels, concrete and cabaret

An influential American composer's 90th birthday box, plus British piano concertos and a father-and-son duo

Cockerham, Manchester Camerata, Sheen, Martin Harris Centre, Manchester review - re-enacting the dawn of modernism

Two UK premieres added to three miniatures from a seminal event of January 1914

Cockerham, Manchester Camerata, Sheen, Martin Harris Centre, Manchester review - re-enacting the dawn of modernism

Two UK premieres added to three miniatures from a seminal event of January 1914

Kempf, Brno Philharmonic, Davies, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - European tradition meets American jazz

Bouncing Czechs enjoy their Gershwin and Brubeck alongside Janáček and Dvořák

Kempf, Brno Philharmonic, Davies, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - European tradition meets American jazz

Bouncing Czechs enjoy their Gershwin and Brubeck alongside Janáček and Dvořák

Solomon, OAE, Butt, QEH review - daft Biblical whitewashing with great choruses

Even a top soprano and mezzo can’t make this Handel paean wholly convincing

Solomon, OAE, Butt, QEH review - daft Biblical whitewashing with great choruses

Even a top soprano and mezzo can’t make this Handel paean wholly convincing

Two-Piano Gala, Kings Place review - shining constellations

London Piano Festival curators and illustrious friends entertain and enlighten

Two-Piano Gala, Kings Place review - shining constellations

London Piano Festival curators and illustrious friends entertain and enlighten

Echo Vocal Ensemble, Latto, Union Chapel review - eclectic choral programme garlanded with dance

Beautiful singing at the heart of an imaginative and stylistically varied concert

Echo Vocal Ensemble, Latto, Union Chapel review - eclectic choral programme garlanded with dance

Beautiful singing at the heart of an imaginative and stylistically varied concert

Scott, Irish Baroque Orchestra, Whelan, RIAM, Dublin review - towards a Mozart masterpiece

Characteristic joy and enlightenment from this team, but a valveless horn brings problems

Scott, Irish Baroque Orchestra, Whelan, RIAM, Dublin review - towards a Mozart masterpiece

Characteristic joy and enlightenment from this team, but a valveless horn brings problems

Classical CDs: Voice flutes, flugelhorns and froth

Baroque sonatas, English orchestral music and an emotionally-charged vocal recital

Classical CDs: Voice flutes, flugelhorns and froth

Baroque sonatas, English orchestral music and an emotionally-charged vocal recital

Comments

Harpsichords do have dampers