The deathless Alicia Alonso, in person | reviews, news & interviews

The deathless Alicia Alonso, in person

The deathless Alicia Alonso, in person

Remembering the woman who was Cuban ballet's legend and monster

The magnificent, controversial Cuban ballerina Alicia Alonso, who asserted that she would live to 200, died yesterday in Havana, aged nearly 99.

Only a small proportion of our conversation got into my published feature article on the festival for the Daily Telegraph at the time, and for historical interest I print a full transcript of it here along with a note of my first impressions of her. Below, I extract some illuminating observations of her artistry and stage charisma from critics, writers and performers, including Edwin Denby, Agnes de Mille and Allegra Kent.  (Image left, Alonso as Zemphira in Massine's Aleko, 1942)

(Image left, Alonso as Zemphira in Massine's Aleko, 1942)

It is November in Havana, Cuba, in 2004. We are in her office in the Ballet Nacional de Cuba headquarters, bright and warm with the sunshine. Alicia Alonso sits, tiny, old, preserved as if by her own willpower in an exotic majesty that feels exciting to encounter. She is all strong colours, wearing a royal blue dress and matching turban, black glasses over her famous eyes, her skin stretched tight over a face that is unnaturally, thickly made-up. Her long curved nose and long red slash of mouth underneath make a forbidding, intense, glamorous impression, like an ancient Spanish duenna. She is reluctant to smile for the photographer, preferring to poke her nose upwards and stretch the lips thinly across the face.

Her ability to have achieved so much on stage for so long in such an athletically precise skill as classical ballet when officially blind remains much discussed, but I don’t doubt that she can see almost nothing, and also doesn’t care about its minor awkwardnesses. Greeting me, she offers her hand to the empty space to my side, before swivelling around at my voice. Later, when our photographer is introduced while he is still depositing his camera bags, she offers her hand far over his head.

Her voice is alto, quite soft, mellow, and rather passionate, with a Caribbean inflection to its Spanish accent.

ALICIA ALONSO: Have you been in our school, the national school? You must, oh, you must see our school, we are most proud of it. It has been a very big effort but we have made already a really good school.

IB: In Britain we have the impression of better and better Cuban dancers, more and more of them. Why?

I think because we get more of a chance to look at all the talents, and there is a future for them. If they have a talent we give a free education, and then if they continue to develop their talent they come into the company – they already have their career.

When you started the first school in the 1940s, what did you find?

Our school at first was paid for by the fathers of all the little girls who wanted to be ballet dancers. Mothers and fathers took them to learn it as an exercise, or as an art – not as a profession, because here there was no profession, really. To be a professional you had to go to other countries. That's why I became professional, but I never really left. Every year I came back here whenever I had time between engagements in the United States. I would put on a school and work with the children, I put on a scholarship to work with children with talent. The first time we tried to make a company was in 1948, with the Ballet Alicia Alonso, which is now the Ballet Nacional.

Was it mostly girls at first? Difficult to get boys?

Oh yes, very difficult, very difficult. We had to go to orphanages, for kids without father and mother, and that's where we got them. A group of them. Our first professional dancers here were from the orphanages. Some of them had mothers, but some had no money to support them so they left them there.

What was the quality in Cuban children that you felt could be good for ballet dancers?

First of all, they have a very good ear for music. And there is an atmosphere here, that makes the muscles warm, you move easily. And rhythm. Don't forget, we are Caribbean, we are mixed, we listen from children to drums and music, to Spanish music and African music, it's quite a mix of good rhythm and music. This we have inside us.

What is your own racial background?

I am Spanish, my background is Spanish. And that was the first dance I learned in my life – when I was a little girl I went to Spain with my father and my mother, and learned dancing there. When we came back from Spain, when I was eight, a private society here had already opened a ballet school, where I started to take ballet. And for the first time I let go my castanets and thought, This is what I like most in my life.

You left for New York when you were only 15?

I married, and I went to New York. I was 16.

Were you very much in love?

I don't think you marry if you are not very much in love. Fernando was the son of the president of the society where I learned dancing. We had known each other from when I was very young. But it was when I was in school in the United States, that he came and looked at me, and said, “That little girl can really dance!” And that's it! [She giggles.]

Did you learn everything you needed to know about ballet in the US?

No, you never learn everything you need to know. Every day, every year, you learn more and more, and even more if you listen to your own experience too. In the US I learned much about the modern way of dance. I danced modern ballet with Agnes de Mille and Eugene Loring, and I learned from people not so classical.

Such as the British choreographer Antony Tudor.

Such as the British choreographer Antony Tudor.

Yeah, I learned with him, so that was very precious. I learned from him how to tell a story in a ballet. He was fabulous. (Image right, Alonso as Tudor's Juliet, 1945)

And even before that, what I learned with Michel Fokine was how to develop a person – when you are a young woman or young man, you have to find the right style, in Les Sylphides, the atmosphere and the style; in Carnaval... With Massine, I learned how he moved the corps de ballet, like a modern way, how to move the masses, big groups, to continue showing these stories. With Balanchine I learned how to listen to music, how to be musical. So you see, if you watch and you listen, you learn every day.

When you set up your school in Cuba, what did you think you were doing? Were your ambitions for it to be a national school?

My ambition was for what I have now, a great school and a great company.

What amazes me is how young you were, 25 or 26.

I was younger than that!

Most young ballerinas usually want to dance as long as possible before they think of doing schools and things.

I wanted to dance – I understand – but I wanted to do this too. It is my life. I dedicated my life to it. It's still my life. And I had the opportunity to do it. I think many ballerinas would like to do that. I found my opportunity… well, I don't know if I found it or made it. I made it. But I have, or I had it to be able to do those things. I had the atmosphere, and the backing of the private society, which was strong in Cuba.

Was that a Spanish society originally that was started by the Alonsos?

No, no, the Pro-Arte was started by wealthy parents in Cuba who wanted their children to have the culture they knew. And they brought all the best artists and singers from the world to come here. So we had a chance to see and hear all this. So all this made an atmosphere right for it.

I gather that in the 1940s and 1950s ballet was quite elitist here in Cuba, but it has changed from being upper-class and exclusive into something for everyone. Was that your conscious intention?

Very conscious. Very conscious. Because you don't know where you will find the talent. It could be anywhere. A family of artists, or a daughter of a miner or taxi-driver. The talent exists, we have to find it. And that's what enriches our school all the time. Every year we audition, and we examine, and wherever we find talent we pick him up and teach him and help him.

Do you think almost all Cuban children could be good ballet dancers?

A very high proportion.

A higher proportion than other countries?

I couldn't say that, because I haven't looked in other countries. But here, I agree, it would be a very high proportion.

I was speaking with Nilas Martins [of New York City Ballet], and he said they want to know the secret of Cuban dancing. He respects your school so much – "She is doing something right here", were his words. When you were deciding how to make your methodology for teaching in Cuba, how did you decide on your teaching base?

By myself. You see, I was the example. I took class from every good dancer and every good teacher I could find. I experimented with my own body, I made my own career, I became a ballerina, and I thought, yes, this is it. And not only are we happy with that mix, that we find with myself as an example, but we find it in people we are watching. Because teaching doesn't stop – you don't say this method is good and that's it.

No. Teaching is like science, you can always find other things, new things, that you could use. No two people can approach one step the same way, you have to explain to one one way, and to another another way; and when you watch a new pupil you have to have good eyes to see exactly what's wrong with them, and you have to explain exactly to them.

I understand. Do you think that attitude – making each individual see the importance – is different to the Soviet system which is less individualised?

I haven't seen Russian teaching lately, but long time ago, years ago, they used to have it. Long time ago, they used to have it. But their way of dancing is like the way they talk, the way of their folklore, the way of their expression. The same thing happens to us – it is the personality of the company, and each country has its own personality. You can see each company dance one ballet and you know immediately their school and where it came from.

The other person I can think of like you was Ninette de Valois who was also only 25 or 26 when she set up the British school..

She did a fabulous job, a fabulous work in England.

She wasn't a first-rate ballerina, like you.

I had the advantage over her, because I could not only talk about it and teach it, but I demonstrated it too. That's an advantage. And when I taught the boys, how to hold me, how to do this so he would look good, I could tell them how to partner.

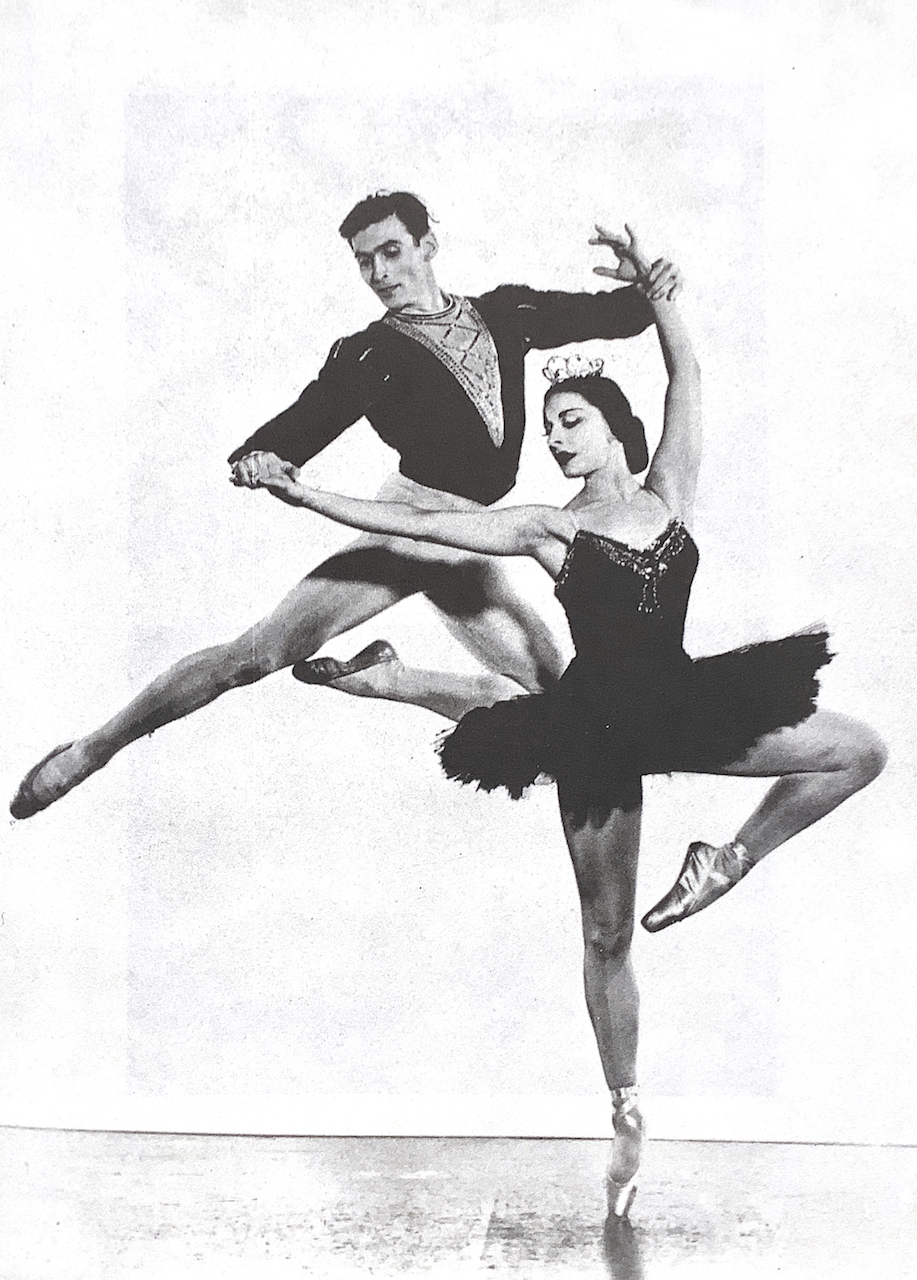

(Pictured left: Alonso and her favourite partner, Igor Youskevitch in Swan Lake)

(Pictured left: Alonso and her favourite partner, Igor Youskevitch in Swan Lake)

What do you look for in a man for dance?

The same thing you look for in a woman: he has to have good physique, he has to have good ears, he has to be an artist, he has to have an imagination for creation. And I don't expect them all to be the same, but they must be smart enough to see what they have inside them. Some of them are more character, some more classical, some have more a romantic feeling. A different personality that will reflect in their art. It's a fascinating world.

I'm trying to understand what makes these special Cuban male dancers.

We teach them that a man must dance like a man, and a woman like a woman. And when they dance together, there must be a contact between them that reflects to the audience. The main thing is each of them have a story to tell, a fire to dance, and they must get to the audience.

A kind of reality... what sort of choreographers seem to you best for Cuban dancers? I’m interested you will have some Frederick Ashton here.

I'm going to fight to do the whole Les Patineurs ballet. I wanted an Ashton ballet.

The whole Patineurs?

I hope so. I hope they don't sue me.

Who will teach it?

We want to see how we can get it later on. But on the opening night of the festival this year I wanted to do the pas de deux because that was the first thing I danced when Freddie [Ashton] came to the US, he put on Les Patineurs for ABT and I danced it.

I wondered why that was there!

It is a very sentimental thing for me. Freddie is doing 100 years this year, no? He has to be here. I know he has other beautiful things but it had to be something he worked with me. Freddie told me to stay in England, when I was first in England with ABT. He wanted me to stay, he said, “Stay, I want to work with you.” In the '40s.

It was 1946.

Right after the war. I was one of the two ballerinas, and Freddie said to me, stay. I said, “But Freddie, I have my house in Cuba, I am too far from here to there, and I have so many things I am trying to do with the company, and here I will be all by myself.” I spoke Spanish with him – he spoke Spanish.

Of course, Ecuador! Did you speak much with Ninette?

Not much.

Because with the similarities of what you did, I wondered.

I remember, Ninette came when I danced. She leaned forward over me and said, “Let me see your feet!” She took my feet and went like this (bending it) because she wanted to see how flexible they were. She was quite a woman. She died?

Yes, she died. She was 102.

She was quite a woman.

You respected her.

I do. I respected her tremendous. And I admired her tremendous.

What about Balanchine? You have a gala for him.

Of course, I worked with him very, very much. He made a ballet for me and before that he worked with me when I was at the academy. It was like a class in the old Maryinsky, he did something very light with me. But the real strong ballet he did for me was Theme and Variations. And I danced Apollo with him. And he directed the orchestra on Theme and Variations. It was his dream to conduct. I tell you, he asked me, “Was it all right?” And I said, “Maestro!” He said, “Too fast?” Ooh, he enjoyed it, tremendous.

The Balanchine work is protected with the Trust. Do you have a relationship with them?

Oh yes, oh yes.

They are very protective.

Yes, sometimes these trusts take so much care of their ballets that they kill them. No companies can do their ballets and before you know it years go by nobody sees them, and you forget.

And Tudor too.

Tudor! And nobody sees them. Nobody sees them.

The political relationship between US and Cuba is very difficult, but I know in the dance world there is great artisticinterest between them.

Yes, very much. We did a tour last year, and it was, “Aahh!” Great success! And a lot of people came from there, some to dance, and some to watch the company.

What do you admire about American dancing? Do you think they are still one of the great dance schools of the world today? Or slipping?

I think...

You are putting on a very diplomatic face! Perhaps you don't want to answer that.

No. Because I love them.

What about other schools for dancing? Have you seen the British school?

We have some pupils who come here. There was a time when they were wonderful, and I think it's a wave that comes down, and I hope comes up again.

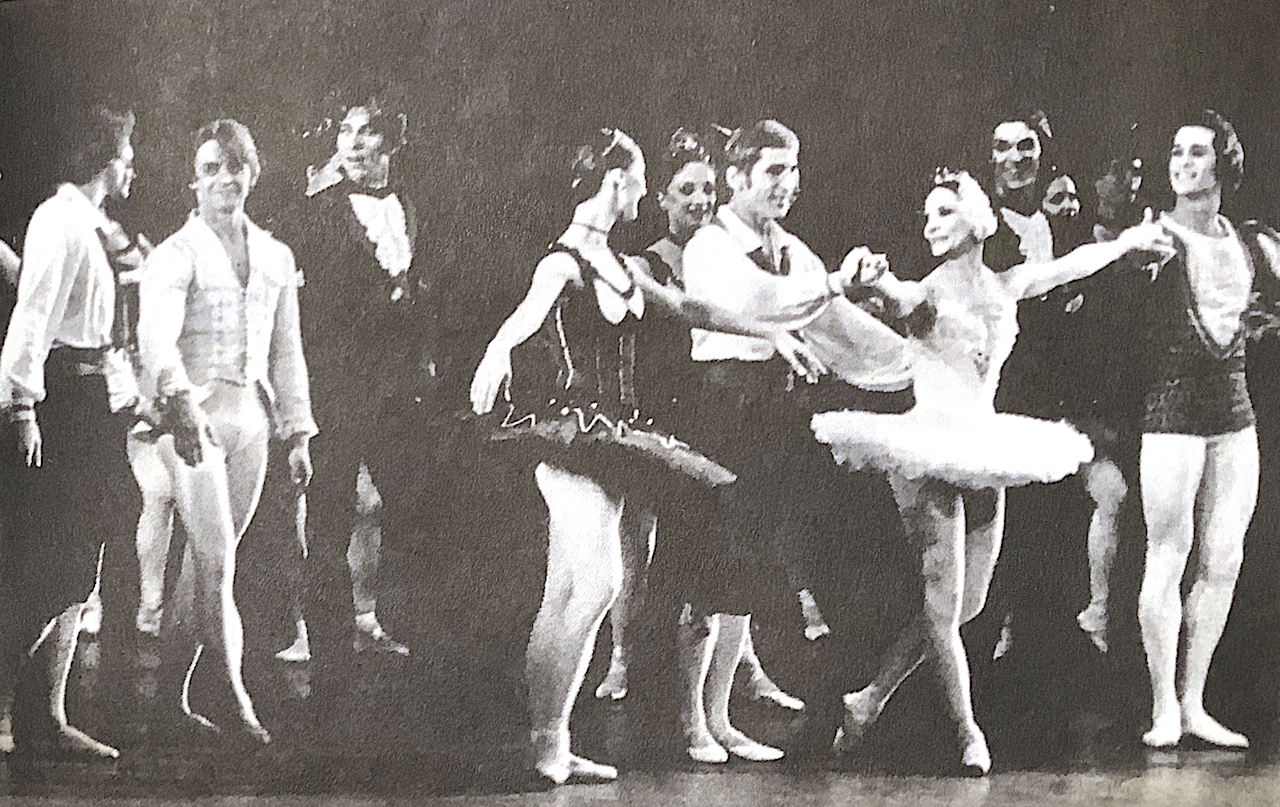

(Pictured right: Alonso with Cuban stars Carlos Acosta and José Manuel Carreño and Argentinian star Julio Bocca, 2002)

(Pictured right: Alonso with Cuban stars Carlos Acosta and José Manuel Carreño and Argentinian star Julio Bocca, 2002)

There is a lot of interest in London in Cuban dancers and teachers. Carlos Acosta dances in London a lot, and José Manuel Carreño danced there two or three years, and Loipa Araujo is enormously admired as a teacher. Do you think there is something about British choreographers or the way the British dance that suits the Cubans?

I like them. Tudor was my biggest pleasure, I like the British sense of music. I like them. I like Freddie, and… well, I knew them. Our world was so well known all together. We were not doing it for money, we were doing it for ballet, art, culture.

I was interested that when Cuban dancers perform abroad they split into either still keeping a relationship with Cuba, like Carlos and José Manuel, or they cut themselves off completely, saying they must have freedom to control their lives.

In the first place, I don't know what they mean by freedom. To be a dancer you have to work very hard, and if you don't work very hard you don't make it. You should get another job and be happier, where you don't have to work so hard physically. For dancing you have to work with your brain and your body. It's a mix of art and athletics.

And culture.

The brain is culture, the brain. Sometimes it's better to belong to a smaller country. They learn everything here, and when they go out they find out that they know more than everybody else around them. They don't understand that. They went out thinking they'd learn something, and then they find out they are ahead of others. I wish I was being born right now, and could get to the school we have now – oh, how wonderful, how wonderful.

It was very hard in the '40s.

Oh, it was very hard.

Back then did you ever think you wouldn't succeed?

No, because I enjoyed it. But if you mean, did I see the company being as it is now? Well I could not see it, but I could want it, though I didn't know if I would make it. Because we didn't have anything. No shoes. We had nothing.

Would the ballet have problems surviving if you didn't have political support for it? I mean, in Britain we have national support.

You have national support?

And France has it, but Spain for instance has no national ballet company.

I am fighting for Spain to have a national ballet company. Castro. Now. Oh yes.

Can you make that happen?

Well, I'm fighting so hard, now. At the festival a group is coming from the Universidad of El Rey Juan Carlos.

So this is a new project you can help with?

Well, I'm fighting for it. Because I think for the arts, for the art of dancing – in my idea of ballet – I think it's a wonderful way, a fusion. It is one of the visions of humanity, more important now than ever to seek that, and for the youth to think of art, culture, how to do it, for them to go to a theatre and be distracted. It's a language of all people you can speak that language of dance in any country.

The public doesn't always share that language, and yet all the Cuban dancers I ask about what makes them dance, all of them say it's the audience here that makes demands on them, makes them want to do more.

Yes. But what I wanted to tell you is important. Men have inside them a brain and imagination, for creation not destruction. And art is a creation of the mind, a creation of the imagination of men. When you see ballet, a good ballet, the imagination creates, it builds you inside. Do you understand what I'm trying to tell you? Not to see bombs and destruction, which we see and live with every day, on television and radio, this killing, that destruction. Earthquakes or wars. No.

You have some very young dancers to be carrying that big idea.

Fifteen, 17, you will see them with the older ones, because I think a company should have a ladder. These young ones are pushing with their energy and these other older ones are teaching with their experience, so they give, and they give, to each other.

How about children used to today's TV and electronic games culture? Culture has changed a lot in the last 10 years.

That's the advantage we have here. We have our children go to school, we pick them up at 5, take them to dancing and they stay until 8, they have dinner, then they study, then they go to bed. We are trying to take them off the streets, and this computer games bwingbwingbwing makes them idiots. Like seeing pictures that should not be shown. [Smiling] I speak very strongly about this.

You see children watching TV and wonder if they are spoiling their lives?

Not spoiling their live, they are confusing themselves. I see it. I watch or listen, and I think, goodness gracious, how can you help them if they get all day long all these confusing things, these games and what they see in the newspapers. So now we teach them something different, we take them to the class to learn art and painting and music.

If you were a mother now, and your children was 10 or 11, it would be hard to keep them focused like that.

We are doing it! We are doing it! You will see them, on opening night – not all of them, because not all can get on stage. You will see only a few, and I am going to see you with your mouth open!

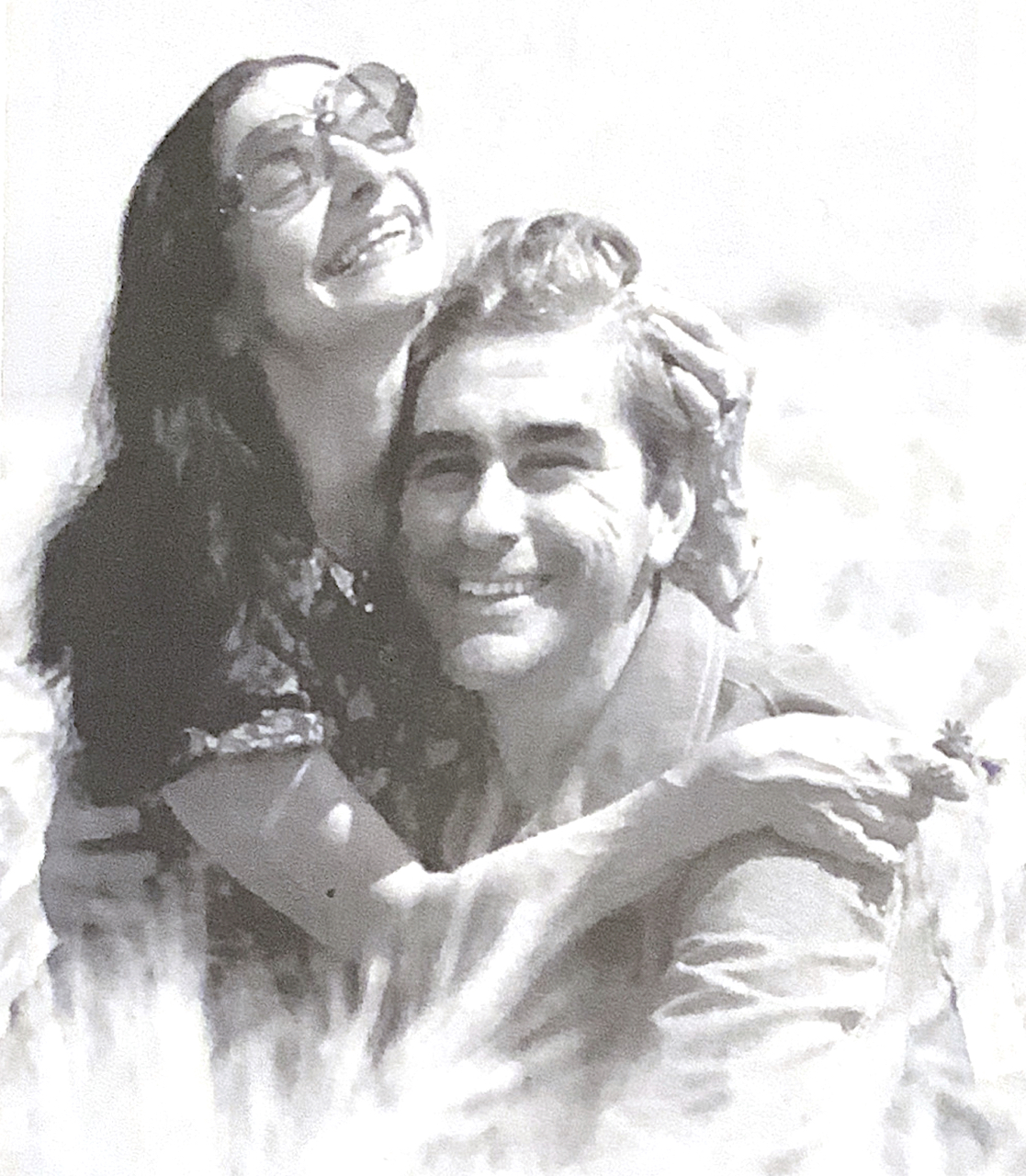

(Pictured left: Alonso with her second husband Pedro Simon)

(Pictured left: Alonso with her second husband Pedro Simon)

Who is the next generation of teachers and leaders who will continue your work?

I expect to live 200 years! No problem.

But seriously...

I have many, many, many pupils, I mean figures like Josefina (Mendez), Loipa (Araujo), Aurora (Bosh), tremendous. Marta Garcia was one of our ballerinas, now directing Teatro Ballet de Colón. They are from all over, and they all feel like this, about this school, and I don't just mean the school but the school of life that we have here, the way of thinking.

There are a lot of people who say ballet is dead, they want to see modern dance. What do you think?

I'm very sorry for them. You can see all kinds of modern and folklore dance, and there is a lot of richness in that, but why must you close one eye when you have two eyes? Why not enjoy everything that is beautiful, that a human being can do with his body? Modern dance can be good, folklore can be good – but for me, ballet is most difficult, because it needs a tremendous training. For me a ballet dancer is like an athlete that breaks records every day.

You have passed some amazing dancing genes to your daughter, you and Fernando. She is a teacher, isn’t she?

Laura, my daughter, is all over the US teaching. In December she is coming back. She is a terrific teacher, a tremendous teacher. She has a good school, a good base. She knows how steps should be done. And something very important – she has very good eyes to watch what's wrong with a person.

Did she get that from you?

She got that from her father too, and myself. A good combination.

She was born when you were very young?

Yes.

How did you manage at ABT?

Oh, I took her around, I'd put her down in class. I had a lady who took care of her. And I remember when I was in a show, Ethel Merman said, “That Cuban girl, come here – you are just a baby.” I said, “No, I'm a mamma.” And she said, “Show me your child!”

So I took Laura over, she was one or two years old, and Miss Merman sat there in the dressing room with all these bottles of perfumes and said, “Let her play here.” And I said “NO!!” I could see my daughter playing with all these bottles, and I was saying, “Oh, Miss Merman, no!” But every day she would say, “Bring me that daughter of yours.” Ethel Merman was a very soft, kind lady. She could look rough, she was rough in life, but soft in heart.

I wanted to ask you about Alicia Markova.

Oh.

Were you friends?

Oh yes. Oh yes. Oh I admire her. She was the ballerina in the company and I respected her tremendous.

You took over many of her roles.

Giselle was the first. Yes, I did. Anton Dolin asked me to dance with him.

You and Markova between you possessed the role of Giselle in New York. Did you feel competition?

Oh, we danced so differently. Well, it was the way we danced that was different, but the idea of the style of the romantic era we had very much alike. This idea of having no weight when you danced. Oh yes. I will always remember, I still have in my head, watching her doing Giselle, the first Giselle I saw in my life... And I will never forget it, it was beautiful.

I don't remember anything in Terpsichore's variation from 1945 but Alicia Alonso pawing the ground like an elegant horse

Above: Alonso centre at the ABT gala of July 28, 1975 with (far left) Rudolf Nureyev and Mikhail Baryshnikov, Cynthia Gregory, and (far right) Erik Bruhn and Jorge Esquivel.

ALLEGRA KENT

[From Once a Dancer] I always wanted to ask Alicia Alonso, “Who is your gynecologist?” When the hormones of an actress diminish with menopause, she can still be an actress. Not so the dancer. But Alicia Alonso danced impressively at 60 and beyond – a phenomenon among phenomena.

ROBERT GARIS

[From Following Balanchine, on Alonso in Apollo] I don't remember anything in Terpsichore's variation from 1945 but Alicia Alonso pawing the ground like an elegant horse.

BERNARD TAPER

[From Balanchine, A Biography, on the 1947 creation of Theme and Variations]. “Alonso, always a splendid technician, seemed better than her best in this ballet, as if Balanchine had invented a new glamorous and radiant personality… The greatest classical ballet of our time, Walter Terry called it in his New York Herald-Tribune review.”

ARLENE CROCE

[On Theme and Variations] A Balanchine jewel.... the beautiful dance poem that Balanchine was able to create while contriving an ingenious simulation of adagio effects for an allegro technician, Alicia Alonso.

EDWIN DENBY

[From Dance Writings, on Alonso's Giselle, 1943] It was brave of her to dance a role not only so exacting in itself but also danced with incomparable brilliance by Miss Markova. Miss Alonso is a dancer of merit, and by good fortune the shape of her head, neck and shoulders is most attractive. In the first lifts of the second act, in the diagonal series of leaps on both toes in the solo that follows, she was lovely to look at. In the first act she had a very remarkable moment of miming just before her death. But neither the plastic clarity of the entire figure nor the dramatic variety of the role was really sufficient. As the first trial in the part by a young dancer who is physically not quite strong enough for it, the performance was admirable; but as theatre this great ballet looked Tuesday night merely charming and quaint. With Miss Markova dancing, Giselle is a tragic action with the most touching and the most mysterious implications; her genius brings its real nature to life. But no other dancer begins and ends a dance phrase as distinctly or gives such dynamic variety to dance phrases as she does.

[On Alonso in 1944] The event of the evening was Alicia Alonso’s dancing. Despite a fall... she triumphed by her purity of style in three different ballets. (In Graduation Ball)she and Richard Reed did their classic pas de deux with a youthful strength that was charming. Earlier she had danced the about-to-be-abandoned mistress in Lilac Garden with a remarkably convincing womanly presence and with no trace of melodramatics; her interpretation was in a different way as fine as the best ones of this role – Miss Kaye's and Miss Karnikova's.

But Miss Alonso’s greatest moment was in the Mazurka of Les Sylphides, where her perfection in the quick accuracy of the leaps, in the lovely bearing of chest, shoulders and head, and in the rapid and exact tripping toe steps was very exceptional indeed. Miss Alonso has a classically modest and undramatic stage presence which is quite her own in the company, and most attractive.

JUDITH CHAZIN-BENNAHUM

[From The Ballets of Antony Tudor, on Undertow, 1945] Tudor said, “I wanted to do a ballet about a murder.” Alonso played Ate, one of two “hideous creatures who would lead all men into evil, [but] appear as sorry and unlikely volunteers for prayer. Although Ate looks petite and innocent, one immediately focuses on her suggestive and salacious expressions... Ate flirtatiously taunts the Satyrisci. She is playfully pushed from one man to another, but she senses danger as they begin to throw her around. Unable to free herself, she is carried off by two men holding her arms, and one carrying her feet. It is a chilling rape scene… One of the most moving episodes in the original production centered on Alicia Alonso’s predatory, insalubrious characterisation of Ate.

AGNES DE MILLE

[From Portrait Gallery, 1990] Alicia’s condition has fluctuated over the years, but she has never regained clear sight… When she reads, watches TV, or attends auditions, she uses high-powered binoculars like a naval commander’s.

Whenever Alicia takes class, she is driven to the school. Whoever has brought her [opens] the car door and [lends] her a supporting hand to guide her up the front steps. In the classroom, however, she walks unhesitatingly and authoritatively right across the open floor to her place at the barre, where she executes her moves on order and on count. When she leaves the barre, she is surrounded by an unhelpful and unsupportive space in which other bodies approach and recede. She asks no favors. She can hold her own.

…Now at 69, an unheard-of age for a classical ballet dancer, Alicia still practices every day and still performs. Occasionally her grandsons partner her.

Alicia Alonso, born December 21 1920, died October 17 2019.

Buy

Explore topics

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Dance

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

iD-Reloaded, Cirque Éloize, Marlowe Theatre, Canterbury review - attitude, energy and invention

A riotous blend of urban dance music, hip hop and contemporary circus

iD-Reloaded, Cirque Éloize, Marlowe Theatre, Canterbury review - attitude, energy and invention

A riotous blend of urban dance music, hip hop and contemporary circus

How to be a Dancer in 72,000 Easy Lessons, Teaċ Daṁsa review - a riveting account of a life in dance

Michael Keegan-Dolan's unique hybrid of physical theatre and comic monologue

How to be a Dancer in 72,000 Easy Lessons, Teaċ Daṁsa review - a riveting account of a life in dance

Michael Keegan-Dolan's unique hybrid of physical theatre and comic monologue

A Single Man, Linbury Theatre review - an anatomy of melancholy, with breaks in the clouds

Ed Watson and Jonathan Goddard are extraordinary in Jonathan Watkins' dance theatre adaptation of Isherwood's novel

A Single Man, Linbury Theatre review - an anatomy of melancholy, with breaks in the clouds

Ed Watson and Jonathan Goddard are extraordinary in Jonathan Watkins' dance theatre adaptation of Isherwood's novel

Peaky Blinders: The Redemption of Thomas Shelby, Rambert, Sadler's Wells review - exciting dancing, if you can see it

Six TV series reduced to 100 minutes' dance time doesn't quite compute

Peaky Blinders: The Redemption of Thomas Shelby, Rambert, Sadler's Wells review - exciting dancing, if you can see it

Six TV series reduced to 100 minutes' dance time doesn't quite compute

Giselle, National Ballet of Japan review - return of a classic, refreshed and impeccably danced

First visit by Miyako Yoshida's company leaves you wanting more

Giselle, National Ballet of Japan review - return of a classic, refreshed and impeccably danced

First visit by Miyako Yoshida's company leaves you wanting more

Quadrophenia, Sadler's Wells review - missed opportunity to give new stage life to a Who classic

The brilliant cast need a tighter score and a stronger narrative

Quadrophenia, Sadler's Wells review - missed opportunity to give new stage life to a Who classic

The brilliant cast need a tighter score and a stronger narrative

The Midnight Bell, Sadler's Wells review - a first reprise for one of Matthew Bourne's most compelling shows to date

The after-hours lives of the sad and lonely are drawn with compassion, originality and skill

The Midnight Bell, Sadler's Wells review - a first reprise for one of Matthew Bourne's most compelling shows to date

The after-hours lives of the sad and lonely are drawn with compassion, originality and skill

Ballet to Broadway: Wheeldon Works, Royal Ballet review - the impressive range and reach of Christopher Wheeldon's craft

The title says it: as dancemaker, as creative magnet, the man clearly works his socks off

Ballet to Broadway: Wheeldon Works, Royal Ballet review - the impressive range and reach of Christopher Wheeldon's craft

The title says it: as dancemaker, as creative magnet, the man clearly works his socks off

The Forsythe Programme, English National Ballet review - brains, beauty and bravura

Once again the veteran choreographer and maverick William Forsythe raises ENB's game

The Forsythe Programme, English National Ballet review - brains, beauty and bravura

Once again the veteran choreographer and maverick William Forsythe raises ENB's game

Sad Book, Hackney Empire review - What we feel, what we show, and the many ways we deal with sadness

A book about navigating grief feeds into unusual and compelling dance theatre

Sad Book, Hackney Empire review - What we feel, what we show, and the many ways we deal with sadness

A book about navigating grief feeds into unusual and compelling dance theatre

Balanchine: Three Signature Works, Royal Ballet review - exuberant, joyful, exhilarating

A triumphant triple bill

Balanchine: Three Signature Works, Royal Ballet review - exuberant, joyful, exhilarating

A triumphant triple bill

Comments

Marvellous interview, thank