In memoriam Dmitri Smirnov (1948-2020) - a personal tribute by Gerard McBurney | reviews, news & interviews

In memoriam Dmitri Smirnov (1948-2020) - a personal tribute by Gerard McBurney

In memoriam Dmitri Smirnov (1948-2020) - a personal tribute by Gerard McBurney

Much-missed composer-polymath remembered by a colleague and friend of 35 years

November 1979… and a small group of Soviet composers (dubbed the "Khrennikov Seven") unexpectedly found themselves the targets of a boorish public assault by that once infamous General Secretary of the Union of Soviet Composers, in a speech at the organisation’s Sixth Congress in Moscow, describing them as “pretentious… pointless… sensation seeking… noisy filth… a so-called ‘avant-garde’…” Dima and his wife, Len

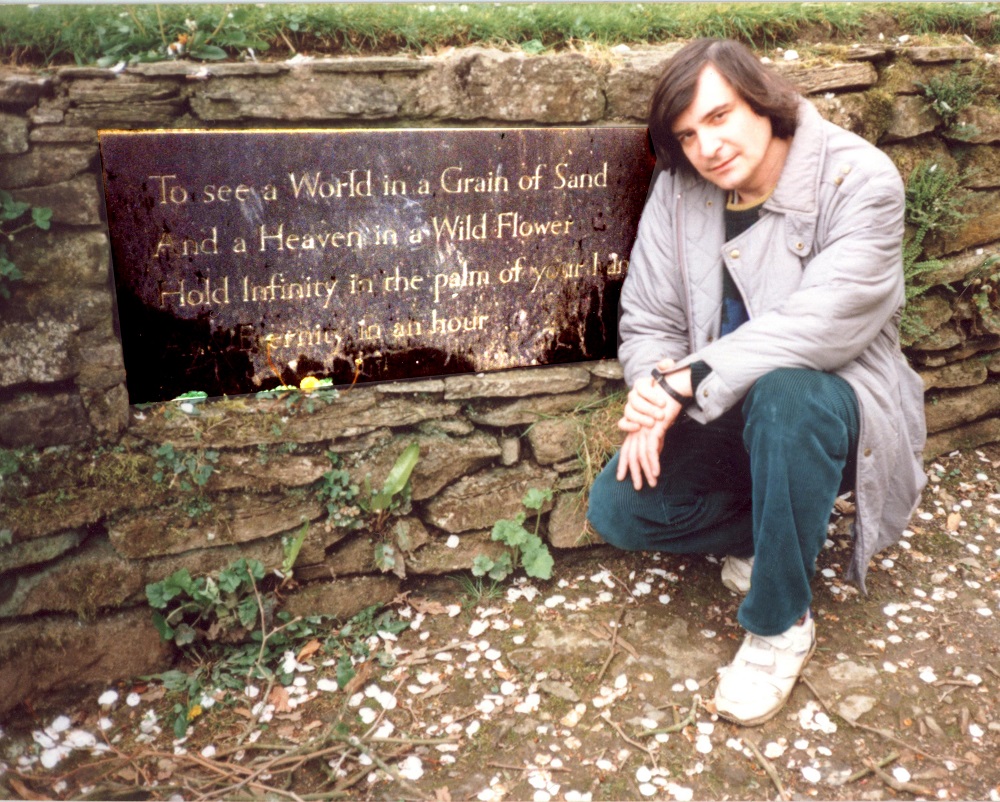

Not long afterwards, I heard about that episode (I think from Elizabeth Wilson or Susan Bradshaw, the two friends who opened Soviet music to me), but otherwise I knew nothing beyond their names of Smirnov and Firsova – apart from some tattered remaindered scores from the bottom of a cardboard box in Collet’s Bookshop on the Charing Cross Road - until I arrived in Moscow in October 1984, and Denisov told me how important it was to get to know them: “They’re among the most interesting of our younger composers here in Moscow.” He stressed Dima’s fascination with English culture and William Blake (perhaps to appeal to my patriotism; Smirnov with famous Blake lines pictured below), before adding something that provoked my curiosity a good deal more: “They know everyone on the new music scene in Moscow. You’ll meet all the other composers through them.”

A few weeks later, Liza Wilson was visiting Moscow and took me to a concert in the Great Hall of the Conservatory, where Rozhdestvensky conducted the Prelude to Dima’s Blake-inspired opera Tiriel. Somehow, I’d expected something abrasive, and I remember how the music surprised us both by its soft and velvety romanticism. And that was when I saw Dima the first time, scurrying on stage to take his bow, crouched down, eyes piercing like a hawk’s.  Not long after, Denisov invited me to his home where he introduced me to Smirnov and Firsova. And, within moments, they had invited me to visit them at their home, which they shared in those days with Lena’s parents (distinguished scientists both), in a long low rather crumbling and old-fashioned block of flats on the Western outskirts of the city, surrounded by birch trees and perched on steep bluffs above the River Moscow. I remember the rattling metro out to Shchukinskaya where Dima was waiting for me as agreed “at the end of the platform,” and walking through the snow, and into the main entrance of the building and through their double front door (with the insulating padding on the outside) and being given indoor slippers (“tapochki”) and stepping for the first time into their room - crammed with scores and books and papers and recordings - for tea and food and talk and music and talk again. For hours, it seems like now.

Not long after, Denisov invited me to his home where he introduced me to Smirnov and Firsova. And, within moments, they had invited me to visit them at their home, which they shared in those days with Lena’s parents (distinguished scientists both), in a long low rather crumbling and old-fashioned block of flats on the Western outskirts of the city, surrounded by birch trees and perched on steep bluffs above the River Moscow. I remember the rattling metro out to Shchukinskaya where Dima was waiting for me as agreed “at the end of the platform,” and walking through the snow, and into the main entrance of the building and through their double front door (with the insulating padding on the outside) and being given indoor slippers (“tapochki”) and stepping for the first time into their room - crammed with scores and books and papers and recordings - for tea and food and talk and music and talk again. For hours, it seems like now.

So, began a friendship of 35 years, not just of love and comradeship and curiosity, but - certainly for me, and I hope sometimes for him as well - a window or doorway to a different world.

As a composer, Dima was fantastically fluent. He could write a piece within hours and orchestrate at ridiculous speed. (“Appallingly fast!”, Lena joshed.) Only the other day, just before he died, he finished his opus 200.

I confess over the years I sometimes lost count and there are pieces of his I don’t know (no reason… just too much to do). But others hang in my memory with extraordinary vividness, and often for personal reasons. Lena was pregnant when I met them, and their son Philip – now a talented artist - was born in April and when I went to meet the new baby, it was spring. And we went for a walk with the baby in a pram and when we got back – for more tea – Dima showed me the Second String Quartet he’d just written as a celebration (based on two cradle songs). And I can still feel the newly completed score in my hands and the distinctive gluey smell of the Soviet manuscript paper and how Dima grinned at me as I read what he had written. And, amazingly, a moment ago, as I was writing these very words, I turned on BBC Radio 3 and there was that same music, now being played in his memory.

The Lento second movement of Smirnov's Second String Quartet, based on music from his opera Tiriel

About a decade ago or so, when I was working in America, he sent me a huge work, a Requiem for singers, chorus and orchestra, and asked whether I could think of anyone who might be interested to perform it, and I replied rather irritably that it would be easier to find a home in a concert programme for a six-minute orchestral overture that could be put together in one rehearsal, and maybe he should think about that. A sour and ungracious Friday afternoon email on my part. And the following Monday morning a brand-new orchestral overture was sitting waiting in my inbox, and a year or so later Riccardo Muti took it on tour with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra to Moscow and St Petersburg.

As with most composers, quite a lot of what he wrote was never performed. After a successful premiere of his First Symphony “The Seasons” (a sumptuous orchestral expansion from 1980 of his beautifully delicate chamber setting of Blake’s youthful Poems on the Seasons), Dima took another small-scale work, to visionary words by the German Romantic Friedrich Hölderlin, and expanded it into his Second Symphony “Destiny” (1982) and sometime later sent it off to the Union for the usual official assessments (music needed permission to be played). The reply, when it came in 1985, was typical of the Lewis Carroll surrealism of that time: “We return the score you submitted. Unfortunately, this music will never be performed, because it sets words by a certain Gölderlin [sic] of whom it is not known what he would have done had he lived to the 1940s.” Hölderlin died, of course, in 1843. And for what it’s worth, and just from reading it, I still think this Hölderlin symphony one of Dima’s most beautiful pieces.

His love affair with Blake was, of course, at the centre of Dima’s artistic life. As well as the First Symphony, there were two operas: the full orchestral Tiriel (Freiburg, 1989); and the chamber opera Thel (Almeida Theatre, also 1989); and a ballet. And a mass of songs and chamber music and, especially lovely, the Sonata No. 6, otherwise called the "Blake Sonata" for his daughter, Alissa.

Alissa Firsova plays the first movement of the 'Blake Sonata'

But there was a great deal else besides, and Dima’s output covers the range, from massive orchestral canvases and concertos for many different instruments, through a bushel of string quartets and other chamber music, to compositions mystical, tragical and comical for all sorts of combinations. There’s some odd stuff in there too; I remember, for example, some extremely ascetic a capella chorales from early in his career, and he never could resist the chance to write for an instrument he’d never written for before, or mark the passing of the years with music celebrating births – especially of his two children – and birthdays and anniversaries and deaths. One could chart a whole narrative of Russian music over the last 50 years simply by reading through the dedications to his friends and colleagues at the top of all his different works.

And that quality of his mind and his imagination brings me to another side of him I think crucial: his role as a chronicler of Soviet and Russian (and later British) musical life. He was a prolific diarist, he and Lena creating volume after volume of detailed records of their experiences and documenting their meetings with everyone they met. Anyone lucky enough to get a chance to study Dima’s writings in the future will encounter a panoramic vision of late Soviet musical life – and post-Soviet musical life - like no other. I teased him that he was the Pimen of his time, referring to the monk-chronicler of Boris Godunov.

There are many fascinating aspects to this wealth of documentation he created: innumerable conversations with the likes of Gubaidulina, Denisov, Schnittke, Silvestrov, Knaifel and others, not to mention Dima’s brilliantly comic and sinister documentations of what he and his contemporaries habitually called “the Soviet absurd”. But probably what was most important to him was his and Lena’s friendship with the exiled Romanian Webern-pupil Philip Gershkovich (or Herschkowitz). Together they studied with Gershkovich and Dima wrote down in astonishing detail Gershkovich’s analyses of Bach and Beethoven (a direct link to the teachings of Webern himself), later published as A Geometer of Sound Crystals.  When not so many months after their son Philip’s birth, Lena became pregnant again with their daughter Alissa (now a composer herself, and a pianist and conductor, pictured above with her mother and father at the Royal Festival Hall, November 2013), I remember expressing astonishment to Sofia Gubaidulina. She laughed: “Those two are very brave!” And when I reported this to Lena she smiled and said: “The thing is… Dima wants everything.” And I see that now. He wanted to write every kind of music. And meet every composer. He wanted to read every book, look at every painting. He wanted a family. He wanted to cherish Lena and her music (as people and as artists, they grew up beside one another like two vines intertwined). And he wanted to document everything. The diaries and the books, of course, but all those priceless photographs, thousands of them. And he wrote poetry and he painted pictures. He cooked and cleaned and organised. And, driven by his passion for the future of his children, he embraced the colossal upheaval of moving to Britain (I remember a painful moment in a café somewhere in London, when I was trying but failing to help him, and he looked at me and said: “I just want this country to be our country.”)

When not so many months after their son Philip’s birth, Lena became pregnant again with their daughter Alissa (now a composer herself, and a pianist and conductor, pictured above with her mother and father at the Royal Festival Hall, November 2013), I remember expressing astonishment to Sofia Gubaidulina. She laughed: “Those two are very brave!” And when I reported this to Lena she smiled and said: “The thing is… Dima wants everything.” And I see that now. He wanted to write every kind of music. And meet every composer. He wanted to read every book, look at every painting. He wanted a family. He wanted to cherish Lena and her music (as people and as artists, they grew up beside one another like two vines intertwined). And he wanted to document everything. The diaries and the books, of course, but all those priceless photographs, thousands of them. And he wrote poetry and he painted pictures. He cooked and cleaned and organised. And, driven by his passion for the future of his children, he embraced the colossal upheaval of moving to Britain (I remember a painful moment in a café somewhere in London, when I was trying but failing to help him, and he looked at me and said: “I just want this country to be our country.”)

And always, at the centre, before and after, William Blake. As well as all the Blake music he wrote, Dima completed the first full-length study of Blake’s life and art in the Russian language. And when he died, he was nearing the very end of his multi-volume translation of all Blake’s writings into Russian. All he had left, Lena tells me, were some pages of Vala, a prophetic work Blake himself did not finish.

Dima, I can’t believe that you are gone. Let alone that you were taken from us - at Easter time, not that you would have cared much about that! - and by this horrible raging virus, and when you still had so much energy inside you, so much music and so many new ideas. At least I know one thing: don’t laugh, and I know I didn’t tell you, but I always thought you were that famous "Tyger, tyger, burning bright!" (I can hear you laughing when you spoke those words to me in English.)

I think it was your eyes.

Explore topics

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

Robin Holloway: Music's Odyssey review - lessons in composition

Broad and idiosyncratic survey of classical music is insightful but slightly indigestible

Robin Holloway: Music's Odyssey review - lessons in composition

Broad and idiosyncratic survey of classical music is insightful but slightly indigestible

Classical CDs: Wolf-pelts, clowns and social realism

British ballet scores, 19th century cello works and contemporary piano etudes

Classical CDs: Wolf-pelts, clowns and social realism

British ballet scores, 19th century cello works and contemporary piano etudes

Bizet in 150th anniversary year: rich and rare French offerings from Palazzetto Bru Zane

Specialists in French romantic music unveil a treasure trove both live and on disc

Bizet in 150th anniversary year: rich and rare French offerings from Palazzetto Bru Zane

Specialists in French romantic music unveil a treasure trove both live and on disc

Scottish Chamber Orchestra, Ibragimova, Queen’s Hall, Edinburgh review - rarities, novelties and drumrolls

A pity the SCO didn't pick a better showcase for a shining guest artist

Scottish Chamber Orchestra, Ibragimova, Queen’s Hall, Edinburgh review - rarities, novelties and drumrolls

A pity the SCO didn't pick a better showcase for a shining guest artist

Kilsby, Parkes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson, Barbican review - string things zing and sing in expert hands

British masterpieces for strings plus other-worldly tenor and horn - and a muscular rarity

Kilsby, Parkes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson, Barbican review - string things zing and sing in expert hands

British masterpieces for strings plus other-worldly tenor and horn - and a muscular rarity

From Historical to Hip-Hop, Classically Black Music Festival, Kings Place review - a cluster of impressive stars for the future

From quasi-Mozartian elegance to the gritty humour of a kitchen inspection

From Historical to Hip-Hop, Classically Black Music Festival, Kings Place review - a cluster of impressive stars for the future

From quasi-Mozartian elegance to the gritty humour of a kitchen inspection

Shibe, LSO, Adès, Barbican review - gaudy and glorious new music alongside serene Sibelius

Adès’s passion makes persuasive case for the music he loves, both new and old

Shibe, LSO, Adès, Barbican review - gaudy and glorious new music alongside serene Sibelius

Adès’s passion makes persuasive case for the music he loves, both new and old

Anja Mittermüller, Richard Fu, Wigmore Hall review - a glorious hall debut

The Austrian mezzo shines - at the age of 22

Anja Mittermüller, Richard Fu, Wigmore Hall review - a glorious hall debut

The Austrian mezzo shines - at the age of 22

First Person: clarinettist Oliver Pashley on the new horizons of The Hermes Experiment's latest album

Compositions by members of this unusual quartet feature for the first time

First Person: clarinettist Oliver Pashley on the new horizons of The Hermes Experiment's latest album

Compositions by members of this unusual quartet feature for the first time

Gesualdo Passione, Les Arts Florissants, Amala Dior Company, Barbican review - inspired collaboration excavates the music's humanity

At times it was like watching an anarchic religious procession

Gesualdo Passione, Les Arts Florissants, Amala Dior Company, Barbican review - inspired collaboration excavates the music's humanity

At times it was like watching an anarchic religious procession

Classical CDs: Camels, concrete and cabaret

An influential American composer's 90th birthday box, plus British piano concertos and a father-and-son duo

Classical CDs: Camels, concrete and cabaret

An influential American composer's 90th birthday box, plus British piano concertos and a father-and-son duo

Cockerham, Manchester Camerata, Sheen, Martin Harris Centre, Manchester review - re-enacting the dawn of modernism

Two UK premieres added to three miniatures from a seminal event of January 1914

Cockerham, Manchester Camerata, Sheen, Martin Harris Centre, Manchester review - re-enacting the dawn of modernism

Two UK premieres added to three miniatures from a seminal event of January 1914

Comments

Gerard. Really good to read

A fine tribute to such an

Lovely tribute, Gerard. I

Caro Gerard, brilliant and

Beautifully written.

Gerard, thank you, You have

A touching, personal tribute

What a wonderful tribute and