William Blake, Tate Britain - sympathy for the rebel | reviews, news & interviews

William Blake, Tate Britain - sympathy for the rebel

William Blake, Tate Britain - sympathy for the rebel

Vast and satisfying show for a visionary and iconic artist

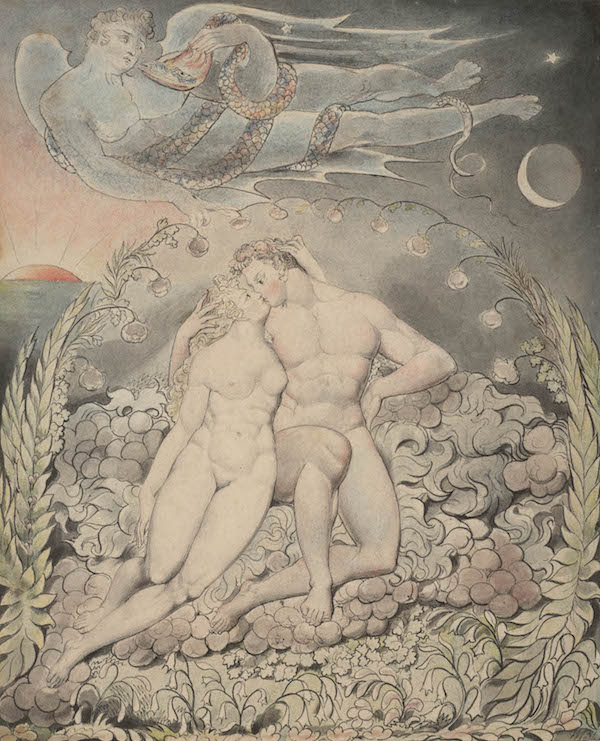

Poor Satan. Adam and Eve are loved-up, snogging on a flowery hillock and all he’s got for company is a snake — an extension of himself no less, and where’s the fun in monologues? Poor, poor Satan. He’s a hunk too, if you don’t mind blue. Coiffed hair and toned arms with a sexy sky slouch. Ever seen such a lovely lounger? Ever seen such a mournful moue? He’s angel worthy of our pity, even if he is fallen.

Much of the pleasure of William Blake’s art derives from seeing things turned on their heads. Inverse, perverse or in verse, his unconventional images and writings were largely unrecognised for much of his lifetime. Now, his work’s iconic. The Tate Britain’s magnificent show of over 300 pieces manages a delicate balance. It celebrates his rebellious vision but firmly emphasises the context in which he was working. As a professional engraver, Blake relied on an inconstant stream of commissions which in turn funded the artistic endeavours for which he is best known. Like many artists, his oeuvre is split between what he did for money and what he did out of fervour (there is of course, much overlap too). He found recognition among a small number of influential people but he never attained the wild successes of his peers, such as sculptor John Flaxman. Consequently he depended upon formal and informal patronage for much of his life. That such a ferocious autodidact should have relied upon so many other people’s good will and aesthetic preferences to fund and otherwise sustain both his professional and his artistic works remains an interesting quasi-paradox.

Much of the pleasure of William Blake’s art derives from seeing things turned on their heads. Inverse, perverse or in verse, his unconventional images and writings were largely unrecognised for much of his lifetime. Now, his work’s iconic. The Tate Britain’s magnificent show of over 300 pieces manages a delicate balance. It celebrates his rebellious vision but firmly emphasises the context in which he was working. As a professional engraver, Blake relied on an inconstant stream of commissions which in turn funded the artistic endeavours for which he is best known. Like many artists, his oeuvre is split between what he did for money and what he did out of fervour (there is of course, much overlap too). He found recognition among a small number of influential people but he never attained the wild successes of his peers, such as sculptor John Flaxman. Consequently he depended upon formal and informal patronage for much of his life. That such a ferocious autodidact should have relied upon so many other people’s good will and aesthetic preferences to fund and otherwise sustain both his professional and his artistic works remains an interesting quasi-paradox.

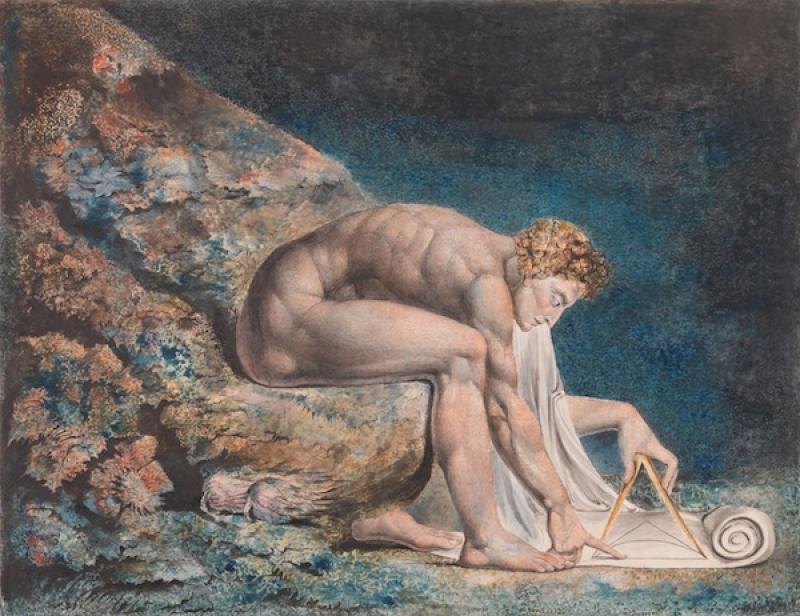

The vast exhibition, curated by Martin Myrone and Amy Concannon, treats Blake as “primarily a visual artist”. But even those who find his poetry obscurantist or naïve must admit him to be profoundly literary. On show, separated into long sequences of individual pages, are Blake’s illustrations for Dante’s Divine Comedy, Edmund Spenser’s The Faerie Queene, John Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress, and of course, Milton’s Paradise Lost. Here, as elsewhere in the exhibition, a patient trail of visitors snakes along each series, their average pace implying looking rather than reading.

Yet without knowing these works, how would Blake have illustrated them — let alone dared fence with Milton’s God? Text and image in his works take on similar aesthetic and procedural properties. The “infernal” printing method he invented in 1788 — which he called “illuminated printing” and now known as relief etching — allowed him to create words and images at the same time rather than by etching images and laying type separately. Visually, words and images bear striking resemblances to each other: the title of America, A Prophecy, 1793, sprouts leaves and vines, while the hand-written text of A Cradle Song, 1789, is almost indistinguishable from its marginal decoration. The page at which the lavishly decorated Night Thoughts, 1795, is opened shows how Blake’s illustrations used space to convey sense; the images mirror the flow of words. The top of the page is shadowed with a darkly winged presence and begins “Where darkness, brooding o’er unfinished fates / With raven wing incumbent”; at the bottom, “Each friend by fate snatch’d from us,” is tugged away by a swiftly flowing channel of water.

Arguably the most splendid example of this interaction between images and text are his illustrations for The Book of Job, 1828. Three of his 22 engravings are on display in the penultimate room of the enormous exhibition. The lines are crisp, the central illustrations compositionally daring, and the outer borders — which according to painter John Linnell were conceived and executed as a afterthought, directly onto the copper and without prior drafting — fluid. One plate, which illustrates God’s rebuke to Job, is encircled with roundels and snatches of Genesis, as if annotating the subtext of God’s argument. Another plate depicting Satan’s ignominious dismissal is surrounded with twining snakes. In a third, the primary forces of land and sea, Leviathan and Behemoth, are depicted as variously comatose or in gasping pain, or spaced and clumpy — hardly the fearsome harbingers of the Apocalypse. Of course, this follows standard Biblical exegesis, but what doesn’t is that Blake makes us feel sorry for these yoked beasts. As an apparently persecuted outsider, Blake identified strongly with Job. Given his depiction of these beasts, perhaps his sympathies lay with them too. They, like him, couldn’t help what they are.

Arguably the most splendid example of this interaction between images and text are his illustrations for The Book of Job, 1828. Three of his 22 engravings are on display in the penultimate room of the enormous exhibition. The lines are crisp, the central illustrations compositionally daring, and the outer borders — which according to painter John Linnell were conceived and executed as a afterthought, directly onto the copper and without prior drafting — fluid. One plate, which illustrates God’s rebuke to Job, is encircled with roundels and snatches of Genesis, as if annotating the subtext of God’s argument. Another plate depicting Satan’s ignominious dismissal is surrounded with twining snakes. In a third, the primary forces of land and sea, Leviathan and Behemoth, are depicted as variously comatose or in gasping pain, or spaced and clumpy — hardly the fearsome harbingers of the Apocalypse. Of course, this follows standard Biblical exegesis, but what doesn’t is that Blake makes us feel sorry for these yoked beasts. As an apparently persecuted outsider, Blake identified strongly with Job. Given his depiction of these beasts, perhaps his sympathies lay with them too. They, like him, couldn’t help what they are.

- William Blake is at Tate Britain until 2 February 2020

- More visual arts on theartsdesk

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Photo Oxford 2025 review - photography all over the town

At last, a UK festival that takes photography seriously

Photo Oxford 2025 review - photography all over the town

At last, a UK festival that takes photography seriously

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](https://theartsdesk.com/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=7tVsLyR-) Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Add comment