A Chorus Line is one of the great American musicals. It opened off Broadway in 1975, rapidly barged a path to a larger Broadway house and proceeded to run for over 6,000 performances, breaking records along the way. Chicago, which opened in the same season, failed to seize the city's imagination in the same way, and had to wait till the 1990s to find an audience prepared to devour it. At the Tony Awards the musical about the foot soldiers of showbiz, the faceless dancers high-kicking in line, went on to win nine gongs, and then picked up a Pulitzer Prize. A Chorus Line soon transferred to the West End, where its success was nothing like as long-lived. It is now back for the first time since then, and it is being directed onto the stage of the London Palladium by the show’s original co-choreographer Bob Avian.

Avian (born in 1937) was there from the start of the first workshop, when dancers paid $100 a week would spill their stories to a tape recorder. Over time, these were slowly developed and shaped into a series of mini-biographies which told of performers in all shapes and sizes, from all ethnic backgrounds, racked by all sorts of anxieties about body image, sexuality, age, ability. Although Avian went on to choreograph a number of blockbuster shows in London, most notably Sunset Boulevard and Miss Saigon, he retains a fierce loyalty to A Chorus Line based partly on the fact that he is one of the very few people left from the creative team.

We said things on that stage that had never been said before

Michael Bennett, its director and co-choreographer with Avian, died in 1987. So did Edward Kleban, the lyricist whose memorable titles for the show include “Dance: Ten: Looks: Three”, “The Music and the Mirror” and the eleven o’clock tearjerker “What I Did for Love”. Book writers James Kirkwood and Nicholas Dante are no longer with us, nor are its costume and lighting designers. And last year saw the death of composer Marvin Hamlisch. Dealt different cards, Hamlisch and Kleban might have had the same partnership as Lerner and Loewe, Kander and Ebb or even even Rodgers and Hammerstein. But A Chorus Line was to remain the only product of the slow organic process of alchemy that happened when they got into the room with Bennett and Avian. Bob Avian talks to theartsdesk about the genesis of the singular sensation that is A Chorus Line.

JASPER REES: Why did this show work then? Why did it land in a way that Chicago in the same year didn't quite?

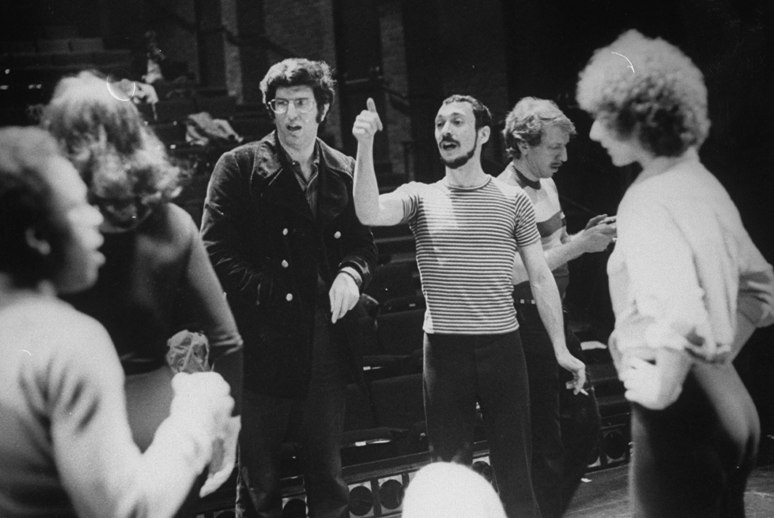

BOB AVIAN (pictured right): I think A Chorus Line spoke to everybody, which shocked us: we didn’t know it would. We had a feeling it would be a really backstage musical appeal and speak to people in the business. But A Chorus Line is about people who are not recognisable people who work in assembly lines in the factories. Whatever, who are not stars, who are everyman. And so we zero in on these kids who want to be a dancer in a Broadway show but when you ultimately see them in that show you don’t know who they are. I think the audience responded to that. It’s the dancing everyman. Michael in previews in New York put in the front of the programme, "this show is dedicated to anyone who has ever marched in line, anywhere, anytime." And that was pushing all the buttons. And we said things on that stage that had never been said before. First of all it was like the sexual revolution was just hitting and then these kids opened up and talked about their sexuality, their homosexuality, masturbation, plastic surgery, their love of parents and hate of parents. And in musical theatre terms it was unheard of. It was not The Music Man. Things were never said on the stage like this that were uncensored. We had the umbrella of the public festival and we were off Broadway in a 299-seat theatre, so we felt protected, not knowing what the future would bring. We had no idea what was going to happen after that. But once we started there was a real buzz in town and you couldn't get a ticket and everyone was hovering - the movie studios and the Broadway producers were hovering. So we had to be very careful. It was very scary.

BOB AVIAN (pictured right): I think A Chorus Line spoke to everybody, which shocked us: we didn’t know it would. We had a feeling it would be a really backstage musical appeal and speak to people in the business. But A Chorus Line is about people who are not recognisable people who work in assembly lines in the factories. Whatever, who are not stars, who are everyman. And so we zero in on these kids who want to be a dancer in a Broadway show but when you ultimately see them in that show you don’t know who they are. I think the audience responded to that. It’s the dancing everyman. Michael in previews in New York put in the front of the programme, "this show is dedicated to anyone who has ever marched in line, anywhere, anytime." And that was pushing all the buttons. And we said things on that stage that had never been said before. First of all it was like the sexual revolution was just hitting and then these kids opened up and talked about their sexuality, their homosexuality, masturbation, plastic surgery, their love of parents and hate of parents. And in musical theatre terms it was unheard of. It was not The Music Man. Things were never said on the stage like this that were uncensored. We had the umbrella of the public festival and we were off Broadway in a 299-seat theatre, so we felt protected, not knowing what the future would bring. We had no idea what was going to happen after that. But once we started there was a real buzz in town and you couldn't get a ticket and everyone was hovering - the movie studios and the Broadway producers were hovering. So we had to be very careful. It was very scary.

Were the songs written for the cast who workshopped the show?

Oh yes, all of them. What we did first was we had those tape recordings that we did one night and then we followed up and did several more of those sessions and then we put together version A of a structure and kept working on that and bringing it down, down, down into some sort of a structure that had a beginning, a middle and an end. Then we started hiring people and everybody who was on the tapes was asked to participate first if they wanted to be in it. Some said "yes", some said "I’m not sure" and a lot said "no". Then when we got to the second workshop some people dropped out, some people came in and we found ourselves doing a composite of many characters and reducing them, taking information from different biographies.

Marvin Hamlisch once said that he wrote many more songs than were finally required.(Pictured left, Hamlisch and Bennett with the original cast © Sony Pictures Classics)

Marvin Hamlisch once said that he wrote many more songs than were finally required.(Pictured left, Hamlisch and Bennett with the original cast © Sony Pictures Classics)

We had a whole opening number that went on for 15 minutes and then we spent three weeks on staging and we just threw the whole thing out. The first song that Marvin wrote that everybody loved, Michael more than anything, was "At the Ballet". And Michael turned to Ed Kleban and Marvin Hamlisch and said, "That's the score." What bothered Marvin and Ed was that it was so specific to A Chorus Line that it didn’t have any commercial possibilities. It was all about the particular attitude in the context of the play. Every composer wants chart hits. And the whole score was becoming like that, whether it was "Nothing" or "The Montage" or "At the Ballet" or "God I Hope I Get It". They were all plot-specific. And then when we got to the end of the play they wrote "What I Did for Love". They pleaded with Michael to let them write this song that might have potential to be pulled outside the score. He was so tough with them about hits and he said, "OK, see what you can come up with," and they wrote that and Michael went, "Oh OK," and sure enough it happened to work because emotionally it was right even though it was a song of generalities. It works great.

'What I Did for Love' from the 2007 Broadway cast album

How did you go about telling that story physically?

We took the material and did not censor it. We took the stories together and did a composite of a dancer's life through different characters, starting when they’re four years old which is the first character, and built a profile of a dancer’s life with the shit they got at home, their problems with sexuality and what they thought they were hiding in their bedroom, their dreams and their disappointments, and basically laid out a profile of a dancer. Ending with landing in New York City, and that’s the first half of the show. And then you have the Cassie character whose career is a flop and she just wants to get back in the chorus - wants to get a job again in a factory - and they’re telling her she’s overqualified. These are things that pertain to every person. And are not barring to people who are outside of show business.

What about the character of a god-like director? The audience sees almost nothing of him, which remains extremely avant-garde for theatre, let alone musicals.

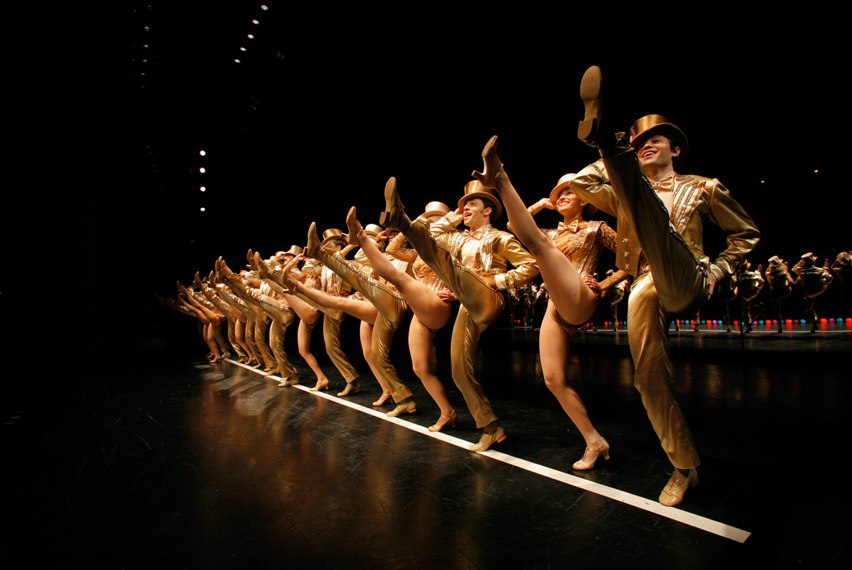

The reality of an audition is you sit in the dark. They can’t see you and you get your clearest perspective of the talent that you’re about to handle. This character even though he’s not seen drives the show. He is the motor of the evening. He is what pushes their buttons. It’s a hard role. It plays havoc with the actor’s ego because he’s got the opening number to establish himself and to make his cause be felt and then for half the show you don’t see him. You hear him, his voice becomes subliminal in your head. And everything he’s asking you take on board and go, "Oh yeah that makes sense," but you don't relate it to the actor. I always have to warn the actor who is up for the role: this is what happens. And then you come onstage and you are dictating the fate of all these characters. You are making the decision: yes you will live, yes you will die. How much did you feel personally responsible for its creation? Did you have a voice in the rehearsal room that gives you a sense of ownership and enables you to carry the torch for the show by continuing to direct it? (Pictured above, 2007 Broadway revival © Sony Pictures Classics.)

How much did you feel personally responsible for its creation? Did you have a voice in the rehearsal room that gives you a sense of ownership and enables you to carry the torch for the show by continuing to direct it? (Pictured above, 2007 Broadway revival © Sony Pictures Classics.)

My voice was in Michael’s head. We worked together for 25 years and we were best friends, brothers, and we met in West Side Story. Michael was 16, I was 21, and when Michael started choreographing he asked me to come and work with him and we even shared a chorus boy apartment for a while. I never was a hired hand so anything I felt I would always say. We’d be on the phone all night long. As his career was taking off he’d call me at 11 o’clock and he’d just tell me everything that was going on. And so our relationship was one of best friends and honesty. I kept on thinking this is the greatest relationship any artist can ever have. Michael wanted to be a star. He wanted to be a choreographer. And I was very comfortable being the best pal. And he took me along with his ambition and was great to me and all of a sudden he was a choreographer, I was his assistant choreographer. He was a director, I was his assistant director. He started to produce, I was his co-producer. Friends would say to me, “Don’t you want to go on your own?” I’d say, “It wouldn’t be better than what this is.” And he was very generous to me with the deals and he wanted me in home base. We had this very unique friendship and working collaboration. And he trusted me. And he relied on me for everything. Emotional support. He was a handful and he was l’enfant terrible but I thought he was a genius. He would be naughty but I always understood where everything was coming from, whether it was his family or his sexual neuroses. I knew his gift was huge and I always made way for that. So why would I ever leave him?

Five dollars, this is the gross for this evening? That would pay the electricity bill for this screening

And then when he got sick it was such a terrible terrible time. He was in Tucson dying and they were asking me to do Follies here in London and he said, “Go do it, go do it, you know the show, it’s the time where you can find your own security and be on your own and you won’t be afraid of the material or working alone.” And it was tough.

When you direct A Chorus Line what is your note to yourself? Are you a keeper of the flame keeping a memory of the original show photocopied on the stage, or are you reinventing it as you see it? What is your role as a director who was there at the start?

To make the performances as truthful as possible. And to not be locked into what was done originally. I have to typecast it because that's what the characters are about. And I even tell them. I say, “I have staging for every line, every word, every number in terms of choreography, but I don’t want to use it if I don't have to. Let me see what you bring and if I think yours is better I’ll go your way. And if I think mine is better I’ll go my way.” Mostly I go my way. Because my way is accenting the orchestration, is musical, but I help them find their performances and if they’re really smart and have originality I love it. You’re working with dancers who are told what to do. They’re not actors per se who have all this acting training. (Pictured below, London Palladium cast. Photograph by Perou)

How much of the choreography is set in stone?

The dancing is. And a lot of it is about focus so you know in a look so there is not a lot of fuzziness going on and that is very important, especially in the world of body mics today, where you don’t know where the sound is coming from. You can have so many people talking onstage but unless they’re focused or you see a hand up or everybody looking, you don’t know who’s saying anything. I spend my whole life now when I choreograph anything, it’s all about focus so the audience knows where to look because the sound in the voices is coming from speakers as opposed to the stage. It’s a whole new way to work. In the original production we only had five shotgun mikes. And everything was tagged by where the mics were and one overhead for “What I Did for Love”. “Tits and Ass”, if you watch her work her way across the front of the stage, she goes from this mic to this mic to this mic back to this mic. Now with the body mics you can loosen it up. So we keep adjusting it to keep up with the modern sensibility.

Why did the 1985 movie verison directed by Richard Attenborough (pictured right with Michael Douglas and the cast) tank so badly?

Why did the 1985 movie verison directed by Richard Attenborough (pictured right with Michael Douglas and the cast) tank so badly?

It took about 10 years and the first thought was [to sell the rights for] like £100,000 and we ultimately sold it to Universal and then Michael and I had a four-picture deal with Universal. It was supposed to be our second picture but Michael and Universal Pictures did not see eye to eye. Even before we made Chorus Line Michael left Universal and went back to New York. They were fine with that too. And then they couldn’t figure out how to do it. It went to Mike Nichols, Sidney Lumet, all these different directors who didn’t know what to do with it, and finally all gave up on it and they gave it to Richard Attenborough. The picture was sold for a lot of money and then got passed from studio to studio and no one knew how to make it. The resulting film still wasn’t right. It wasn’t a success. It’s not the show. I live in a small town in north-west Connecticut and it had opened on Broadway and it wasn’t doing well and it was playing in a local theatre and I go by myself and it’s a Monday night, one dollar night, I paid my dollar and five people are sitting there. Five dollars, this is the gross for this evening? That would pay the electricity bill for this screening. It lost everything that the show was about.

Add comment