Choreographers are not generally household names, but Matthew Bourne must come close. Not only does his company tour frequently and widely, with a Christmas run at Sadler’s Wells that many families regard as an essential fixture of their seasonal celebrations, his pieces have also been seen on Sky, on the BBC, and on film, most famously when his Swan Lake featured at the end of the 2000 movie Billy Elliot. This month he’s set to become even more widely known, as a film version of his show The Car Man is shown in dozens of UK cinemas.

Bourne, who was knighted in the 2016 New Year Honours for services to dance, does far more than reinvent well known ballets and operas, of course. He has choreographed for West End musicals and done his own play for the National Theatre (Play Without Words). He’s an astute businessman, having run his company – previously Adventures in Motion Pictures, now New Adventures – for 30 years with only intermittent Arts Council funding. The charitable arm of the company, Re:Bourne, sponsors a £40,000 choreography award, and does impressive amounts of outreach work, including running dance workshops for thousands of boys and young men across the UK as part of the 2014 Lord of the Flies tour. His company is one of the UK's busiest and most successful dance troupes.

All of this might give Bourne grounds for complacency, if not arrogance, but the affable London native shows no signs of either when we meet at Sadler’s Wells for a chat about storytelling, Shakespeare, and dance on the big screen.

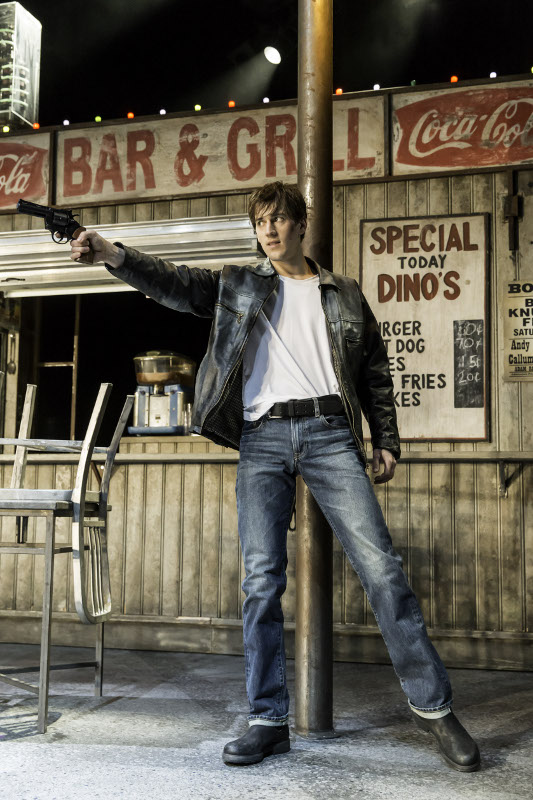

HANNA WEIBYE: It must be exciting for you that The Car Man (pictured below right) is going to multiplexes as well as arthouse cinemas. There’s a lot of dance on TV that wasn’t there 15 or 20 years ago, and there are also highly successful movies without dialogue – like L’Illusioniste and The Artist. Could those two trends come together? Do pure dance films have the potential for box office success?  MATTHEW BOURNE: When you go along to see one of those live ballet broadcasts there will be quite a lot of people there: there’s an audience for that. I think Sadler’s Wells should move into it more, not just the Opera House. It wouldn’t be as widely seen initially, but the audience would grow.

MATTHEW BOURNE: When you go along to see one of those live ballet broadcasts there will be quite a lot of people there: there’s an audience for that. I think Sadler’s Wells should move into it more, not just the Opera House. It wouldn’t be as widely seen initially, but the audience would grow.

I’ve always tried to push dance on film myself, although you can feel movie people blank over a little bit when you say there’s no words and no songs, they can’t quite imagine it. Having done Play Without Words on stage I did pitch to do a Film Without Words after that; I would have loved to develop it, but nobody wanted to so it never came about. Companies seem to want plum titles – Cinderella, that sort of thing. We even got as far as doing recces up in Scotland for filming Highland Fling, but it never happened because the title wasn’t so well-known. The ones that have happened are the big Tchaikovskys and the ones with the titles.

The kind of pitch you want for your shows – between popular and highbrow – makes me think of the 1930s and '40s British culture scene, when “high” culture outfits would tour and perform in music halls, and going to the ballet, for example, was mass entertainment. Obviously you weren’t around then, but were you inspired by that sort of entertainment culture?

I see my current company as very similar to what I’ve read about the history of the Royal Ballet in the war, touring and doing eight shows a week with the same dancers. It would never happen nowadays in ballet! New Adventures works extremely hard, harder than any other company. They do a lot of shows, plus daily class, and lots of rehearsals for new casts coming in. They have to do class and they have to finish class – if they don’t finish, you want to know why – and they have to get their 10-15 minutes before to do their own warm-up. It’s very strict and over the years that discipline has grown and grown – mainly brought in by Etta Murfitt (Associate Director of New Adventures), who’s very strong on all that stuff. It works! And the dancers are happy to do it.

My background in entertainment started long before I knew anything about dance. I’ve always lived in London and my parents were fans of movies and theatre: they took me to see a lot. I loved theatre and movies and that’s what I knew of entertainment. That’s what keeps feeding me now – I love to see straight plays more than anything else. That grounding in that sort of entertainment was very important to me.

I love ballet – anything by Ashton

I go to the theatre a lot. I’m happy that The Caretaker’s coming back and I saw The Homecoming – I’m a big Pinter fan. I’m a bit bored with Shakespeare at the moment, I feel there’s too much. I’ll get slammed down for saying this, but a five-year gap would be a good thing. There are too many Hamlets around – although, contradicting myself, I am absolutely thrilled that Glenda Jackson is going to be playing King Lear. I saw her years ago when I was a kid and she’s an amazing stage actress. She’s so powerful, old school, like watching a Victorian actress on stage.

I watch a lot of TV – that’s where I think the best drama’s being done. I watched War and Peace. A lot of people thought it was a bit Mills and Boon, but I thought it was a good way of winning people over, very cleverly done, and beautifully done. I also never miss EastEnders or Strictly, ever!

What about dance? What other choreographers do you make a point of seeing? Who do you think is unmissable?

I love Mark Morris. I always go to Pina Bausch. I go to a lot of ballet; it’s what I first loved about dance, even before contemporary dance. I love anything Ashton. It was great to see The Two Pigeons again lately – it brought back a lot of memories. It’s incredibly dated, but it still really got me. I used to see it a lot when I first started to enjoy dance at the Opera House; I saw lots of casts, have lots of memories. Over the years I’ve learned to love all sorts of things: Balanchine, Jerome Robbins, I love Agnes de Mille.

I always mention the ones that people know about, but actually there were people earlier, like Lindsay Kemp. Or Lea Anderson, who was in the year above me at college and was very influential on me about forming a company as well as the sort of work she was doing. I sometimes forget to mention the people who have disappeared off the scene. But they were big for me, theatrical influences.

It was interesting watching Christopher Wheeldon’s triple bill at the Opera House the other day: everyone might think I would be more interested in the story piece, but actually I got more involved in an emotional level in the other pieces, which are just pure delight in invention. I enjoy watching things like that, partly because I think “Oh, I could never do that.” You admire things that aren’t your strong point, whereas it’s harder for me to watch a story piece.  You think you could have done it better?

You think you could have done it better?

I have a different view on story pieces to some people: when I see a list of very complicated names and historical figures in a programme I feel as if I need to know too much ahead of it. I like to just watch things!

You don’t put synopses in your own programmes at all.

No, and I don’t read programmes before I see things, I don’t even get them any more. I did the same with Strapless (pictured right): I just waited to see if the piece could tell me the story.

It wasn’t Wheeldon’s high point as a narrative piece – his Winter’s Tale, for instance, is much better.

I did enjoy his Winter’s Tale, but you’ve really got to know the play.

Despite being bored with Shakespeare on stage, have you ever been tempted to do Shakespeare yourself? Romeo and Juliet is a really obvious story ballet you haven’t tackled...

Yes, that might come. A Midsummer Night’s Dream is appealing, lots of lovely characters to play with and it lends itself to movement very well. Any thing that’s a bit supernatural or otherwordly like Dream or The Tempest would be good.

The sort of plots I like working with are really simple plots and fairy tales that everyone has a little bit of knowledge of, so you can then play with that knowledge. In Sleeping Beauty, for example, people know that true love’s kiss wakes her up. I can’t tell them that but everyone knows it already, so I can use it in the story. You ask yourself “Do the audience know this, and if not how will they get to know this?” If the answer is “I’m going to put it in a programme note”, then do something else.

Your fondness for simple plots that everyone knows makes me think of George Lucas, who famously used Joseph Campbell’s The Hero with a Thousand Faces (1949) for inspiration when writing Star Wars.

There’s a great book called The Seven Basic Plots [by Christopher Booker, 2004] – I love that book; it supports me in everything I do. Yes everything has been done before, it’s a this kind of story or a that kind of story I’m telling. I always go back to that book to see what sort of story I’m telling – what have I missed out, what’s the beat I’ve missed out in the story? I’m very into that: simple storytelling, communication.

A dance critic wrote in one of the weeklies the other day that ballet has lost its direction with story, and all the choreographers who’re good at story are in contemporary now. Why do you think that is?

Dancemakers can be afraid of the obvious sometimes

The point she made, which I really appreciated, was that the choreographers she listed (of whom I was one) are people who are trying to bring the heart to stories, trying to make us feel something, and I think that’s interesting. It used not to be the case – [previously] ballet was the one you went to to lose your heart and get a bit dreamy. And of course that can still happen in some of the old pieces.

But dancemakers can be afraid of the obvious sometimes. Audiences like to be clear, generally, so they can allow themselves to give to the piece in some way. In ballet sometimes I think there’s a lot of movement that’s tied up in not telling us much, so you’ve got to dig a bit deeper to tell the stories through the movement.

If you think about what happens in films, we’re quite far behind in dance sometimes with the stories we tell. People make a fuss about Ed Watson kissing Matthew Ball in Strapless. Someone described it as a passionate kiss and I thought, that’s not a passionate kiss, it’s just a peck on the cheek – father and son it looked like to me!

That was our mission when we first did Car Man, actually: bringing a truth and a reality to dance. If we’re going to have sex, we’re really going to go for it; if we’re going to kiss, we’re going to kiss. If there’s going to be a shot, there’s going to be blood. In Giselle, when she gets the sword and stabs herself, there’s never any blood there! Why not?! It makes it more dramatic if there’s blood. Car Man was a reaction to some of that, to try and make dance theatre more realistic.

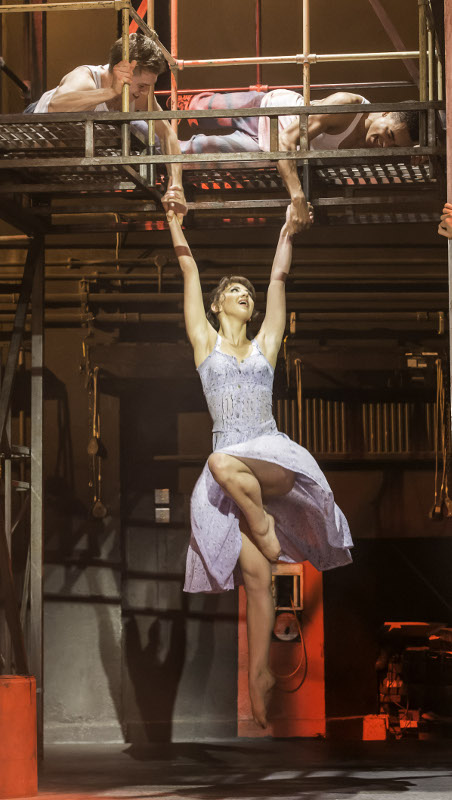

It’s the favourite of the company to perform, actually, because it’s closer to them as people. They can identify with it, and they have a relaxed kind of energy in it that’s different to a technical or a rarefied piece. They get very involved with it. Plus, it’s a lot of sexy stuff, which they always enjoy doing [chuckles]. And the public just love the drama of it – the melodrama of it (pictured below: the shower scene in Bourne's The Car Man.)

It is very dramatic and intense. As a story, I found it curious because there doesn’t seem to be an obvious motive force for what goes on it; the whole, violent spiral seems to kick off just for the slightest of reasons.

The fate theme is so important, the idea of two people meeting and something that’s unplanned just happens. They surprise themselves – for instance, Lana, the main female character, hadn’t realised how much she wants to get out of this place. It’s the spiral of events, and the effect it has on other people, which I find interesting.

If there’s a villain in the piece, it’s her in a way, but I try to give her a bit of sympathy – she’s a caged animal in that place. I try to subvert the clichés: the lead figure male ends up being impotent, uninteresting, a drunk and a slob, not the man she thought she was with at the beginning, and she becomes the stronger figure – she’s the one who shoots him at the end. The same with Angelo, who starts off as the weaker character and becomes the stronger. Those things interested me: the psychological arc of the individual characters and how it affects everyone else around them

The twist in the middle really gets me, where effectively Angelo gets punished for what the others did. It’s really nasty!

[laughs] Thank you! I try to make them suffer. I did it with the prince in Swan Lake too: I wanted him to have more things to be unhappy about before he gets to meet the Swan. I always figure that’s storytelling, asking “How far can we go with that?” The more you’re into one state, the more you’ll feel when it changes. The bigger the journey the better!  Would you say your performers have a house style, a New Adventures style? And is that important for the storytelling?

Would you say your performers have a house style, a New Adventures style? And is that important for the storytelling?

I might not have said that a few years ago, but yes, I think there is now.

We get most of our performers now from either ballet or musical theatre, very few from contemporary. Both of those genres are about giving, the whole style is about performing out all the time. It’s the beginning of storytelling, the want to give to an audience. Those schools have been more enthusiastic about engaging with us as well. Since last year we have been engaging with the contemporary schools more, and we’re going in again doing mock auditions, rep, workshops, just to see if there’s a marriage there or if they’re turning out a different kind of performer. Maybe those graduates don’t want to come into companies where they’re performing a rep, maybe they don’t think it’s for them – that’s something for us to find out. It’s been an interesting year for that.

The quality of dance training in musical theatre colleges has gone up enormously – four of our Prinicipal in Sleeping Beauty are from Laine's! And Zizi Strallen (pictured above left), who plays Lana in The Car Man, has a musical theatre background – and she’s just won Outstanding Female Performance at the National Dance Awards for Car Man, which is quite amazing, for someone with a musical theatre background to win that.

Do you let people have a lot of freedom in interpreting roles?

Yes, I like the freedom. It’s useful to have a living choreographer around to allow you to do that. It’s also how we keep renewing the pieces. I’m not particularly nostalgic for original casts: I like to rework, I like to rethink, and that's how we keep the pieces alive, especially on long tours. The mixes change, partnerships change, everything mixes up all the time.

Lord of the Flies is an extreme version of that, in some ways, when the whole supporting cast changes in each city! Have many of those boys gone into professional training?

That has been a great project. And lots of them are in training. Lots of them message me all the time, I’m constantly giving advice – they’re asking me what kind of college they should go to. A lot of the ones who aren’t old enough to start training yet are involved in legacy projects in their cities too. They come to our shows when we’re in the city and we catch up with them. It’s an amazing project, a useful project that really made a difference. It’s confirmed we’re going to do it in Australia next year, which is brilliant!

We have a training aspect to the company as well - we’re big enough to acccommodate some new people alongside the old people and they all learn from each other. I think we’re one of the few companies that does take graduates, especially when we do Swan Lake, which needs a larger company. Quite often it’s their first job. If we can get our space eventually, I think we’d like to set up our own youth company.

- Matthew Bourne's The Car Man is showing at cinemas across the UK from 1 March. See New Adventures live in Sleeping Beauty, on tour in the UK until May 2016

Add comment