This week Scottish Ballet opens its new season with a ballet of genius that began life in the bath. The bath is a great place for inspiration. The Greek mathematician Archimedes discovered the law of hydrostatics in it. The choreographer Frederick Ashton also had one of his major lightbulb moments while having a soak, idly listening to the radio in 1947 when a new piece of music came on.

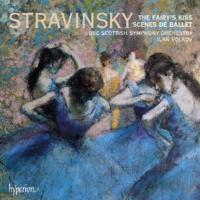

“It was the most fascinating and perfect music for dancing,” he thought, but he’d missed the name of it so rang up the BBC, who told him it was from America and there was no English recording. After much toing and froing Ashton got it sent from America. It was a Stravinsky piece called Scènes de ballet, written as an interlude in a 1944 New York revue called The Seven Lively Arts.

This (as the title indicates) was a celebration of top stars in many fields, from theatre to painting. The showman producer Billy Rose wanted only people who could be described as “the greatest in the world”. Cole Porter did most of the musical part, but Rose wanted ballet too. The brilliant British stars Alicia Markova and Anton Dolin were chosen as “the greatest dancers in the world” and when Markova said Stravinsky was the “greatest composer in the world”, Rose asked him to compose a dance piece.

Markova was intensely proud of her involvement in the birth of this score with its atmospheric fusing of classical, revue and jazz worlds (though Dolin was far less enthusiastic - and it was he who had to choreograph it). She remembered, “My first entrance was a tremendous run down a long ramp. The impression as I raced down, past the ice-blue and white backdrop, was exactly that of looking out of an aeroplane window onto a cloud-dotted blue sky.”

Stravinsky, based by then in Hollywood, was well in tune with the sharp new showbiz world. When Rose telegraphed him: “YOUR MUSIC GREAT SUCCESS STOP COULD BE SENSATIONAL SUCCESS IF YOU WOULD AUTHORISE ROBERT RUSSELL BENNETT RETOUCH ORCHESTRATION STOP BENNETT ORCHESTRATES EVEN THE WORKS OF COLE PORTER." Stravinsky replied: "SATISFIED WITH GREAT SUCCESS." This music, then, came ready-attached with razzamatazz.

Stravinsky, based by then in Hollywood, was well in tune with the sharp new showbiz world. When Rose telegraphed him: “YOUR MUSIC GREAT SUCCESS STOP COULD BE SENSATIONAL SUCCESS IF YOU WOULD AUTHORISE ROBERT RUSSELL BENNETT RETOUCH ORCHESTRATION STOP BENNETT ORCHESTRATES EVEN THE WORKS OF COLE PORTER." Stravinsky replied: "SATISFIED WITH GREAT SUCCESS." This music, then, came ready-attached with razzamatazz.

Hearing it in a gloomy post-war world, Ashton was transfixed by its rhythmic compulsion, the syncopations, the pauses, the mystery it evoked. He was, as Scottish Ballet’s artistic director Ashley Page points out, in probably the greatest period of his great career: in between Symphonic Variations and Cinderella, both of which have a similarly daring and electric choreographic response to rhythm.

“Scènes de ballet comes from that period when Ashton seems to be surging forward with his own choreographic development and examining classicism from a rather more modern point of view. The Sadler’s Wells company had just moved into the refurbished Royal Opera House with that great big stage, and he was obviously thinking on a grander scale. He seemed to be wanting to make more virtuosic, athletic movement and responding to the spikier modern rhythms of Stravinsky and Prokofiev in particular. Most of the previous works he did were very much of a demi-caractère type, more in keeping with the music-hall and revues, but there was a toughness about these three works in the Forties, and a rigour in the use of the classical technique, which is a new departure for him.”

Trying to decide on the new ballet’s look and theme, Ashton quickly rejected the densely intellectual proposals of friends for some sort of exploration of death and rebirth. Influenced by his admiration for Balanchine, he decided on a neo-classical piece of abstract, rather mathematically devised ballet, but dressed in the latest Parisian chic. He asked a precocious 20-year-old designer, André Beaurepaire, who was the darling of Jean Cocteau and le tout Paris (and considered himself arrogantly Picasso’s equal), to do the costumes and sets. (Right, Beaurepaire and Margot Fonteyn in 1948, working on Scènes de ballet)

Trying to decide on the new ballet’s look and theme, Ashton quickly rejected the densely intellectual proposals of friends for some sort of exploration of death and rebirth. Influenced by his admiration for Balanchine, he decided on a neo-classical piece of abstract, rather mathematically devised ballet, but dressed in the latest Parisian chic. He asked a precocious 20-year-old designer, André Beaurepaire, who was the darling of Jean Cocteau and le tout Paris (and considered himself arrogantly Picasso’s equal), to do the costumes and sets. (Right, Beaurepaire and Margot Fonteyn in 1948, working on Scènes de ballet)

Rapidly they fell out. “Tiresome and superficial,” Ashton sniped about the lad to his friends; Beaurepaire sniffed at Ashton’s classical taste ("No diamonds!" he insisted) and produced intricately fantastical pavilions and viaducts that the choreographer jettisoned one after another. In the end, the costumes, now iconic with their ice-blue, primrose yellow, black and white colouring, and sophisticated little berets and jewelled chokers, were mostly Ashton’s idea. And yes, they had diamonds on them.

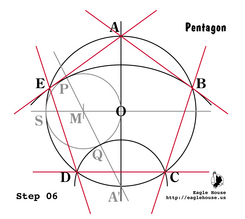

As for the choreography, Ashton hared after an idea entirely new to his usual methods of spontaneous work with dancers in the studio. Although he had been useless at maths at school, he suddenly became obsessed with geometry. He bought a second-hand copy of Euclid’s geometrical theorems and proceeded to drive his dancers (led by Margot Fonteyn and Michael Somes) mad.

“I wanted do do a ballet that could be seen from any angle - anywhere could be front, so to speak,” he said. “So I did these geometric figures that are not always facing front - if you saw Scènes de ballet from the wings, you’d get a very different but equally good picture. We got into terrible tangles (in the studio), but when it came out I used to say, 'QED!'” (Left, Euclid's pentagon)

“I wanted do do a ballet that could be seen from any angle - anywhere could be front, so to speak,” he said. “So I did these geometric figures that are not always facing front - if you saw Scènes de ballet from the wings, you’d get a very different but equally good picture. We got into terrible tangles (in the studio), but when it came out I used to say, 'QED!'” (Left, Euclid's pentagon)

It sounds radical, but in fact geometry has long played a key role in dance patterning, whether tattoos or ballroom formation. The symmetrical lines and circular patterns of Ivanov’s Snowflakes in The Nutcracker and his swans in Swan Lake are as much dependent for their poetic imagery and spatial dimension on floorplan geometry as Merce Cunningham’s sublime modern pieces, conjured in a more fractal way on computer. All great dance is spatial sculpture - it is what the word choreography means.

When Scènes de ballet came to stage in 1948, it radiated mystery and a sort of Vogue chic. Beaurepaire’s pavilions looked surreal, the dancers had a glamorous otherworldliness about them, a subtext of some narrative just out of reach. The central woman has two superb solos: one “a diamond, sparking and utterly chic,” as the great Ashton ballerina Antoinette Sibley has described it, the other “a black pearl, very mysterious. I used to think I was in a kasbah... The music oozes.”

Though the ballerina role is a challenge of the highest degree, particularly to the combination of exact balancing and the off-centre body that Ashton loved so much, the five supporting male roles also asked for a polished dash and graphic dynamism that had not been seen before in British male dancing. No doubt the higher standards produced by the return to the company of young men after the Second World War helped here, but it was also that Scènes has a specific graphic signature. As Ashley Page points out, it’s the downward V that stamps an indelible print on this work. Arms point icily to the floor, the arabesque leg line is powerfully sharp and low, the head flung back. The men’s jumps are steely and precision-sprung. And though the ballerina’s relationship with the men echoes The Sleeping Beauty, she treats them like disposable fragments of her dream, a contemporary young woman masterminding her fantasy, rather than a figment of it. (Right, Fonteyn and Somes in the 1948 premiere production)

Though the ballerina role is a challenge of the highest degree, particularly to the combination of exact balancing and the off-centre body that Ashton loved so much, the five supporting male roles also asked for a polished dash and graphic dynamism that had not been seen before in British male dancing. No doubt the higher standards produced by the return to the company of young men after the Second World War helped here, but it was also that Scènes has a specific graphic signature. As Ashley Page points out, it’s the downward V that stamps an indelible print on this work. Arms point icily to the floor, the arabesque leg line is powerfully sharp and low, the head flung back. The men’s jumps are steely and precision-sprung. And though the ballerina’s relationship with the men echoes The Sleeping Beauty, she treats them like disposable fragments of her dream, a contemporary young woman masterminding her fantasy, rather than a figment of it. (Right, Fonteyn and Somes in the 1948 premiere production)

As a Royal Ballet School student Page had watched and learned Scènes de ballet and since coming to Scottish Ballet as its Artistic Director had long hoped to introduce it. “The only Ashton we’ve done before is Façade, but in my continued development of the company and its dancers I waited until I felt they were ready for it - which is a good seven years into my directorship. But still it is a challenge, as I believe it always will be to the highest level of dancers.

“There is a purity about it which is the classical end of the vocabulary but which Ashton then invents on top of, pushing it to ever greater heights. And it’s not just the men, those 12 women are very much pushed through their paces. For its comparatively short length it feels pretty epic. And it’s perhaps a sign of how Ashton’s maturing craft was able to say all he wanted in such a succinct way, and sum up that score. This is a masterclass in how to make an abstract ballet to an abstract score.”

Below, watch The Royal Ballet's Miyako Yoshida dance a solo from Scenes de ballet, the one photographed with Fonteyn above:

- A version of this article appears in Scottish Ballet's new programme for their Geometry and Grace bill (which includes a Val Caniparoli world premiere and Ashley Page's Fearful Symmetries)

- Scottish Ballet's performances this autumn are at Glasgow Theatre Royal 16-18 September (book here), Edinburgh Festival Theatre 23-25 Sept, Aberdeen His Majesty’s Theatre 1-2 Oct, Inverness Eden Court Theatre 8-9 Oct

- André Beaurepaire's site

- Ilan Volkov and the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra released a recording of Scènes de ballet earlier this year

Add comment