They should use the whole Yeats line: "A terrible beauty is born". The programme, A Beauty is Born, being terrible, I mean, rather than the Beauty, which is Matthew Bourne's Sleeping Beauty, his latest dance work, which isn't terrible at all, just a mite disappointing. And it strives a great deal higher and with more aim to stimulate than Alan Yentob did in this stock documentary from the BBC's flagship arts strand. Is Yentob the most uninterested specialist presenter on TV?

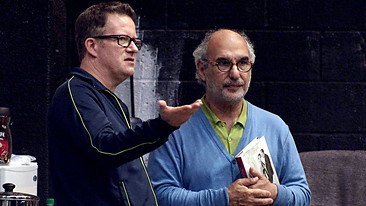

With that morose stare, he's a terrible advert for arts-loving for a start, leaving a chill as he wanders among the efforts of artists with his Imagine team, turning the magical spark of imagination into ash like the Fairy Jobsworth. Yentob seems not very interested in dance, and certainly he didn't muster much interest here in explaining the imagining, the building up of instincts and memories, visions and risky climbs into the head and heart - all the things a documentary about a new alternative Sleeping Beauty production was crying out for. (Yentob pictured below right with Bourne)

Here's a challenge, after all - to be as popular as Bourne is, how much do you compromise with gaining that popularity? The genial Bourne, having applied emotional inventiveness and witty humour twice before to classical ballets Swan Lake and The Nutcracker, was attempting to discover something equally original on its own counts in a landmark ballet score that comes with the most dauntingly complete theatrical packaging in all dance history. Swan Lake and The Nutcracker both have glaring holes in their original creative processes, into which Bourne had stepped with cheek and refreshing courage. But here - how do you de-imagine a total masterwork, and re-imagine it, hoping to attain just as much emotional strength?

Here's a challenge, after all - to be as popular as Bourne is, how much do you compromise with gaining that popularity? The genial Bourne, having applied emotional inventiveness and witty humour twice before to classical ballets Swan Lake and The Nutcracker, was attempting to discover something equally original on its own counts in a landmark ballet score that comes with the most dauntingly complete theatrical packaging in all dance history. Swan Lake and The Nutcracker both have glaring holes in their original creative processes, into which Bourne had stepped with cheek and refreshing courage. But here - how do you de-imagine a total masterwork, and re-imagine it, hoping to attain just as much emotional strength?

Not questions Yentob put in the film, which was a "Let's make a ballet" backstage story that fell back heavily on a herogram for Bourne's 25 years of popularity without analysing his dialogue with today's public. Greasepaint and costumes are the stalwarts of dance-show TV; the corsets and wigs, the wiry bodies in close-up, sound design, lighting, the mysteries of touring with travelators, the fascination of manipulating five baby puppets, as well as the maddening indecisiveness of Bourne's choreographic process, all of this was timelessly diverting.

And his Sleeping Beauty is camera-friendly, an extremely beautiful show with florid time leaps and soft-gothic fantasy costuming, designed by Lez Brotherston, that made a welcome visual counterbalance to the less rewarding "creative" rehearsal scenes. Unlike, say, in classical ballet or with the radical computer-choreographer Merce Cunningham, there is not a framework of movement language or vocabulary to appreciate while it’s being manipulated. The dancers are less "dancers" than dancing actors. Bourne, who concedes he’s more interested in creating the characters than the dance steps, works out his choreography in a muzzy, indistinct way.

Ideas chased through the programme but very few were lassoed. The pre-recording of the music posed interpretative problems to the conductor, Bourne explained, since none of the choreography had been done at that point, so the musicians couldn’t mentally “see” how to shape the playing to the dancing that it would later serve. We learned something.

Take any atavistic fear - being raped when you’re asleep, or having someone else’s children foisted on you - and you could hide it in a fairytale

And the writer on fairytales Marina Warner made comments on the significance of symbolism in fairy tales - and how each generation reshapes them to hide or bring out the atavistic fears and suspicions inside them - that sent up a whirr of questions asking to be asked. As she pointed out, take any atavistic fear - eg, being raped when you’re asleep, or having someone else’s children foisted on you - and a storyteller could hide it in a fairytale like the original Sleeping Beauty. Over the generations, the ingredients, softened, beautified and adapted into prevailing morals and manners, “are turned into entertainment. I think that’s civilising,” she smiled.

Now I’d say it should be Yentob’s pleasant duty to whack that penetrating ball over to why, say, Bourne’s Swan Lake worked so well and whether this ballet would work equally well. I should have liked to know how Bourne meant to deal with the demand for symbolism and emotional ritual that lies in ballets and fairytales, and whether turning The Sleeping Beauty into a contemporary comedy on Twilight movie lines was enough to satisfy his own, personal sense of challenge. There was, to be fair, a glimpse of Mats Ek’s grotesque alternative Sleeping Beauty (where she pricks herself with a syringe of heroin and abandons herself to drugs) - but then Yentob made a telling remark that it was “not intended for the same audience” as Bourne’s.

Well, why did he say that? Does he himself define the audiences as different? It’s one of the insidious falsehoods perpetuated by Yentob in this programme, and popular with “culchur” types in power at the moment, that there are good and bad audiences; that to find an audience who have never gone to ballet is good - as if people who do go to ballet are bad, for one thing, and for another, as if people who go to ballet don’t go to see Bourne and enjoy his productions.

Well, why did he say that? Does he himself define the audiences as different? It’s one of the insidious falsehoods perpetuated by Yentob in this programme, and popular with “culchur” types in power at the moment, that there are good and bad audiences; that to find an audience who have never gone to ballet is good - as if people who do go to ballet are bad, for one thing, and for another, as if people who go to ballet don’t go to see Bourne and enjoy his productions.

“People come to see your work who might be intimidated by classical ballet,” Yentob told Bourne. A vision jumped into my mind of the former Controller of BBC One feeling intimidated by all the millions and millions of ordinary people who love The Nutcracker and Swan Lake, but that would be silly.

Again - why not quiz producer Cameron Mackintosh on why he so enthuses about Bourne’s “new, different” audiences, which alienates half his paying regulars by implying he would prefer they weren’t there? Following that logic, no art form (or indeed company) would ever be permitted to develop devotees at all. A central question for an arts programme in these times, I'd say.

In between the cosy bits, the dance critic Luke Jennings batted another explosive ball into the air. He said Bourne had once told him, “The trouble is that the public has got it into its mind that modern dance is boring” - and he thought, “To a great extent he’s right.” Was there an undertow of anxiety that the choreographer might have given up some riskier ambitions in order to please? And what would the genial and instinctively candid Bourne say had he been asked that?

We must keep asking questions, even if Yentob doesn’t.

Add comment