Black-Out Ballet: The Invisible Woman of British Ballet | reviews, news & interviews

Black-Out Ballet: The Invisible Woman of British Ballet

Black-Out Ballet: The Invisible Woman of British Ballet

Mona Inglesby brought ballet to the masses - then vanished

In 2006 an elderly dancer died in Bexhill-on-Sea, Sussex. She was 88, and had once been one of Britain's most recognised ballerinas. Why did she die in obscurity? Why is the great ballet company that she ran now a forgotten name? This was what I set out to explore in a BBC Radio 4 documentary which aired yesterday. Inglesby's story has the improbability of an epic.

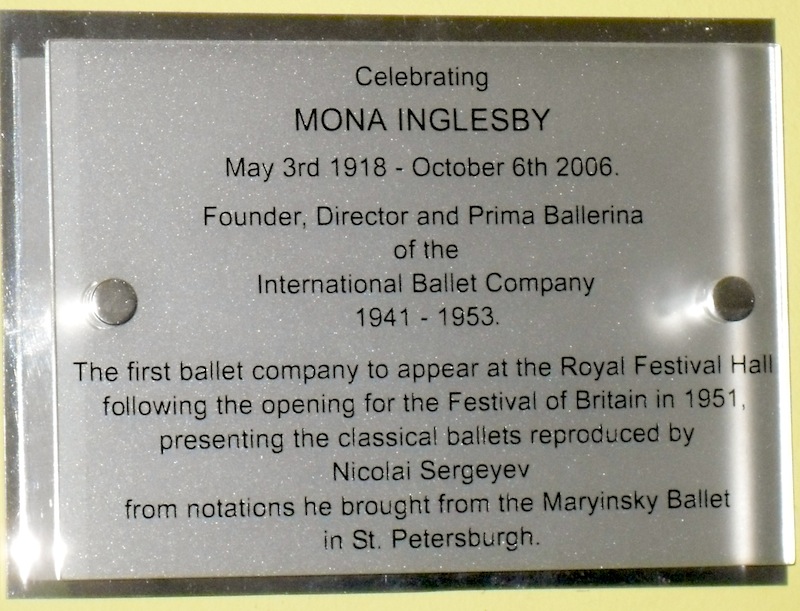

The documentary, Blackout Ballet, produced by Philippa Ritchie, opened with the success of their lobbying to have a plaque installed inside the Royal Festival Hall's stage door (pictured below left). This is the full transcript of the programme.

Sound of public event - speech: "Ladies and gentlemen, good afternoon and welcome to the Royal Festival Hall to celebrate, to acknowledge the work of International Ballet and the joy International Ballet have brought to the South Bank Centre...”

ISMENE BROWN: The Festival Hall on London’s South Bank, 60 years after its opening during the 1951 Festival of Britain. A group of dancers gather for a reunion.

"...I am particularly pleased to see you all here...

IB: The youngest dancer here is in her 70s – the oldest nearly 90. They’re members of International Ballet, which was once Britain’s largest ballet company, and introduced more people to ballet in its time than any other.

"...this whole day is for the acknowledgement of the work of Mona Inglesby.”

IB: When the Royal Festival Hall opened, the company chosen to perform in front of the Queen was not one of the companies famous today - the Sadler’s Wells Royal Ballet, or Ballet Rambert, or even The Festival Ballet – it was International Ballet. And yet these days hardly anybody has heard of this large British classical ballet company and its founder and star Mona Inglesby. And these old dancers are here trying to put right half a century of injustice.

IB: When the Royal Festival Hall opened, the company chosen to perform in front of the Queen was not one of the companies famous today - the Sadler’s Wells Royal Ballet, or Ballet Rambert, or even The Festival Ballet – it was International Ballet. And yet these days hardly anybody has heard of this large British classical ballet company and its founder and star Mona Inglesby. And these old dancers are here trying to put right half a century of injustice.

(ANGELA BAYLEY): We all felt she hadn’t had any recognition for what she’d done – it’s ridiculous

(THELMA CLIFFORD): I don't know who will put it right, really, other than the likes of the few of us here, because a lot of us are sadly gone on our way.,

(PAULINE WHITE): They would never have seen these ballets had it not been for Mona Inglesby - no, they wouldn't.

IB: I stumbled across this invisible woman of ballet almost by accident - when I was writing an article about a reconstruction by the world-famous Kirov Ballet of the original Sleeping Beauty as it was at its premiere in 1890. There was a strange link to an English ballerina - She had been famous, but she was now quite hard to track down. I found her living in a care home on the Sussex coast. She was in her eighties, a small, elegant woman with a quiet manner and white hair. She said she was surprised I’d found her, and she was resigned to being forgotten - she said the establishment had always had it in for her. But the fact was that she’d run what for many years was Britain’s largest ballet company - the International Ballet.

1951 NEWSREEL VOICE-OVER: “One export that Britain can be particularly proud of is ballet, an art in which we might reasonably claim to be leading the world. And in Zurich recently members of the International Ballet of London were combining the pleasures of foreign travel with the useful business of earning hard currency...”

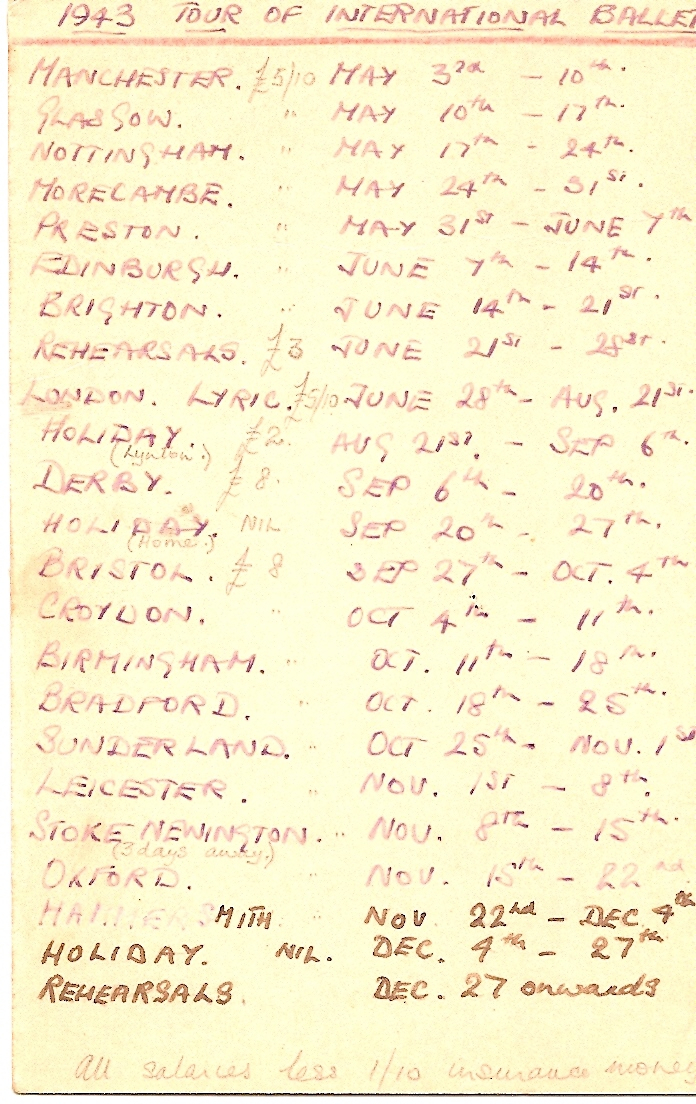

IB: Mona told me she was 22 when she had the idea of starting a ballet company. It was wartime, and she was driving an ambulance in the Blitz when she felt that she could be just as valuable by entertaining the public in the blacked-out theatres. She was a talented young dancer - the famous Marie Rambert had spotted her as a teenager, and she was sure she could do it. Her father lent her £5,000 for the first year on condition she paid it back. The International Ballet opened in Glasgow in May 1941 and for 12 years they were totally self-supporting at the box office. Mona must have been an unusual young woman. What was she like? I asked Moira Tucker who was 17 when she joined International Ballet in 1943.

IB: Mona told me she was 22 when she had the idea of starting a ballet company. It was wartime, and she was driving an ambulance in the Blitz when she felt that she could be just as valuable by entertaining the public in the blacked-out theatres. She was a talented young dancer - the famous Marie Rambert had spotted her as a teenager, and she was sure she could do it. Her father lent her £5,000 for the first year on condition she paid it back. The International Ballet opened in Glasgow in May 1941 and for 12 years they were totally self-supporting at the box office. Mona must have been an unusual young woman. What was she like? I asked Moira Tucker who was 17 when she joined International Ballet in 1943.

MOIRA TUCKER: I was frightened to death of her.

IB: But she wasn’t much older than you.

MOIRA: No, she wasn’t, no. But she had a very quiet, controlled manner about her. Withdrawn, a bit aloof, I found that rather frightening.

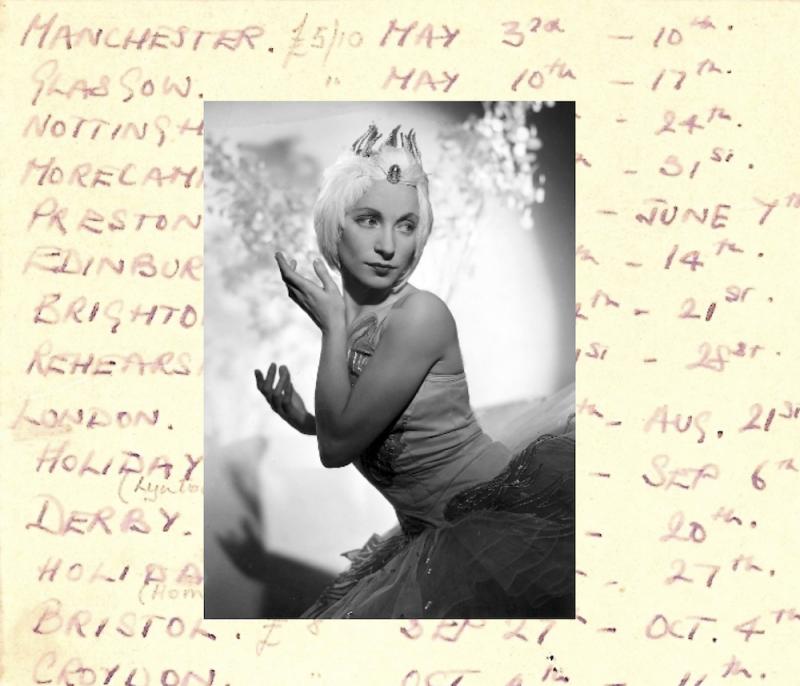

IB: What appeared as Mona’s aloofness was partly because she was reserved by nature. But she was also younger than many of the people she employed which would daunt anybody. And then there was the convention of the times - her first balletmaster, the former Ballets Russes star Stanislas Idzikowski, told her as the director she must command respect from a distance, and she must be addressed as “Miss Inglesby” by the dancers, not “Mona”. From that point - Mona told me - her only friend was her beloved dog Copper (the two pictured left), who went wherever the company did on their constant travels.

MOIRA TUCKER: She was a dancer, first and foremost, I think. Musically she was faultless. But there was a lot of unpopularity and a lot of horrible write-ups we had which were really unfair. She didn’t have the ideal ballet figure, which is terribly tall and slender, she had a strong body. But she just flew across the stage. You find modern-day ballet dancers don’t know how to do that. In The Sleeping Beauty there’s a lovely place where Tchaikovsky’s music becomes enormously buoyant and she had an entrance from upstage left, right across the stage, and it was breathtaking. I watched for this every night.

MOIRA TUCKER: She was a dancer, first and foremost, I think. Musically she was faultless. But there was a lot of unpopularity and a lot of horrible write-ups we had which were really unfair. She didn’t have the ideal ballet figure, which is terribly tall and slender, she had a strong body. But she just flew across the stage. You find modern-day ballet dancers don’t know how to do that. In The Sleeping Beauty there’s a lovely place where Tchaikovsky’s music becomes enormously buoyant and she had an entrance from upstage left, right across the stage, and it was breathtaking. I watched for this every night.

[MUSIC: Sleeping Beauty - Rose Adagio]

IB: Dancers Noel Bronley and Rhona Cooke joined after the war.

NOEL BRONLEY: It wasn’t unusual to do an all-night journey and then continue, get there next day, and then performance on Monday

RHONA COOKE: It was quite a fun time, we had our picnics, washed the celery in the toilet basins! I mean, how we survived health-wise, I don’t know, but we did - we were tough.

NOEL: One of the things I loved was that principals who’d received bouquets on the Saturday night, when they turned up for train calls they’d have made a buttonhole from the flowers to wear in their coat.

IB: So you really dressed up to travel?

RHONA: Oh yes, when we had press receptions Mona told us you must wear little hats. I had a little hat, a little velvet bandeau.

IB: Another dancer was Henry Danton. He’s now 94 and still teaching around the world. Mona hired him as her partner for the company’s first big West End appearance, two months on Shaftesbury Avenue in 1943. The military call-up had caused havoc for ballet companies, and Danton - who’d been invalided out of the army - was a prize catch, even though he’d only had one year of training.

HENRY DANTON: As far as the men were concerned it was whatever she could get, there were ex-actors and she had an American boy who just happened to be there and people who were not called up for various reasons and people who'd been invalided out of the army. It was a real hodge-podge of all sorts.

IB: What were conditions like for dancing in the war?

HENRY: Oh, it was awful. We'd arrive in a new town looking for digs in the dark, carrying our suitcases. Rationing was awful, we'd have these little stamp things and when we went on tour the landlady would take all the butter and sugar and all the eggs, and we got bread and potatoes and bread and potatoes. Some of them were all right but the majority of them ... it was really very hard. (Right, Danton's snap of colleagues, winter 1943)

HENRY: Oh, it was awful. We'd arrive in a new town looking for digs in the dark, carrying our suitcases. Rationing was awful, we'd have these little stamp things and when we went on tour the landlady would take all the butter and sugar and all the eggs, and we got bread and potatoes and bread and potatoes. Some of them were all right but the majority of them ... it was really very hard. (Right, Danton's snap of colleagues, winter 1943)

RHONA: We dreaded the weeks when we were going to be in digs with any of the girls from the local variety theatre because they used to wear fake tan and the bath would literally be orange, it didn’t get cleaned out And we used to share 2 in a bath and think nothing of it. It was the only way to get a bath!

IB: Many people had their first taste of ballet thanks to Mona Inglesby’s company. Her son, Peter Baxter Derrington - born after the company closed - remembers his mother talking about her urge to show ballet to as many people as possible.

PETER BAXTER-DERRINGTON: For her the more people that saw ballet the less elitist it became.

IB: Where did that come from - that she wanted to get away from elitism in ballet?

PETER: I think it probably came from fact she was not Establishment herself. Her father Jimmy was a patents agent, who did extremely well, I hasten to add, but they were not part of what I can only imagine was the social class structure of the time which was clearly fairly rigid. Between 1946 and 48 audited accounts showed that her company had danced in front of 1.67 million people in this country alone.

IB: People living in austerity found their imaginations touched by the escapism and grandeur of the International Ballet’s productions. Some of the key people who steered British arts today were among them; the director of Birmingham Royal Ballet Sir Peter Wright and the former Proms chief Sir John Drummond both fell in love with ballet as teenagers when they saw International Ballet. Another was the son of a Durham miner, John Dowson. After his father died, his family moved south to join relations in London - where his life was changed one night. I went to visit him in a church hall in Cambridgeshire where he still teaches ballet.

[SOUND: John Dowson teaching children with music from Don Quixote]

JOHN DOWSON: My uncle Ron who was just too young to be a soldier in the war, took me to see this ballet and it was the International Ballet. I’d never been to ballet before and he took me to the Coliseum and we sat right upstairs in the gods and I think it was Sleeping Beauty – I was hooked.

JOHN DOWSON: My uncle Ron who was just too young to be a soldier in the war, took me to see this ballet and it was the International Ballet. I’d never been to ballet before and he took me to the Coliseum and we sat right upstairs in the gods and I think it was Sleeping Beauty – I was hooked.

[MUSIC: Sleeping Beauty - Garland Waltz]

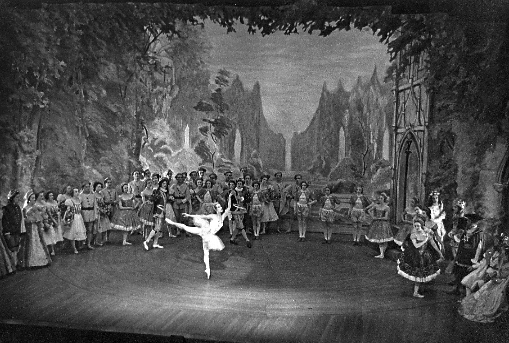

JOHN: I’d never heard music like that - it was fantastic. I came from very working-class background, the costumes wonderful. The ballerina was probably Mona. I think I first registered her at the cinema in Clapham - she used to go into cinemas, prices were very cheap, they were cinema prices. She would go in with 60 dancers plus and a full orchestra plus all the backstage people. Masses of people to keep in work basically. (Above, the International Ballet's Sleeping Beauty)

IB: International Ballet’s fans felt passionate about it - here’s a letter to the popular ballerina Sandra Vane, which her son Simon Zolan showed me.

SIMON ZOLAN: 2nd July 1947, from a person in Sheffield: "My dear Sandra Vane, I cannot let tonight pass without thanking you for your exquisite dancing in Coppelia...

[Music: Swanhilda’s waltz from Coppelia]

...For anyone getting depressed in the small North and among the ills of the commonplace your loveliness and grace was like sunshine coming alive. My heartfelt gratitude to you and your companions for bringing back the realisation that culture and poetry still exist. Yours sincerely."

IB: It’s easy to forget how young Mona Inglesby was - considering the major talents she attracted: future stars of the Sadler’s Wells Ballet such as Harold Turner and the very young Moira Shearer, who’d later become world-famous through the film The Red Shoes. Another of Mona’s hirings was Maurice Béjart, later one of the world’s most extravagant choreographers of mass ballet. But London critics who had initially been warm in the war became cooler after it, as Rhona Cooke and Noel Bronley remember.

NOEL: Whenever you opened something like The Dancing Times you saw a snide remark, didn't happen when the local papers wrote us up they were always absolutely bubbling with enthusiasm and praise weren't they?

RHONA: Absolutely, I've got newspaper cuttings from all over the country and there was never anything nasty like that at all - totally accepted and praised.

IB: I wanted to get to the bottom of this so-called prejudice. Clement Crisp of the Financial Times is the most distinguished and senior of today’s dance critics, a historian with a long memory. After the war eager young critics were mostly focused on developments in London at the big two, Ninette de Valois’s Sadler’s Wells Ballet and the Ballet Rambert. Where did Inglesby fitted in, I asked Clement Crisp?

CLEMENT CRISP: She’s a very interesting figure. I thought it was extraordinary bravery. I think she found there was nowhere where she could work as she wanted to work in the established dance companies at the time. So with a certain amount of youthful abandon she decides to get some money from her papa and start out. I saw the company '46, '47 through towards its end. Its classical stagings were actually very well worth seeing. Going out to the Gaumont State cinema in Kilburn to see The Sleeping Beauty was a remarkable experience because we didn’t know those classics then as we know them now. They were something fresh and interesting. And there were some beautiful sets, for example Mona Inglesby used Rex Whistler – you do not ask for anything better. (pictured right, Mona with Henry Danton in Les Sylphides, designed by Rex Whistler, photo courtesy Henry Danton)

CLEMENT CRISP: She’s a very interesting figure. I thought it was extraordinary bravery. I think she found there was nowhere where she could work as she wanted to work in the established dance companies at the time. So with a certain amount of youthful abandon she decides to get some money from her papa and start out. I saw the company '46, '47 through towards its end. Its classical stagings were actually very well worth seeing. Going out to the Gaumont State cinema in Kilburn to see The Sleeping Beauty was a remarkable experience because we didn’t know those classics then as we know them now. They were something fresh and interesting. And there were some beautiful sets, for example Mona Inglesby used Rex Whistler – you do not ask for anything better. (pictured right, Mona with Henry Danton in Les Sylphides, designed by Rex Whistler, photo courtesy Henry Danton)

IB: Their role in taking ballet outside London to the rest of Britain, was that really what was uniquely theirs?

CLEMENT: Yes, I think it was. You’d go in a theatre or she would play in cinemas, hurrah for her. Though I was never enraptured by some of the company’s performances, what it gave me as a boy was a sight of what these ballets were about.

IB: I asked Peter Baxter-Derrington if his mother talked about the criticism she often got.

PETER: She did tell me that she found the British critics utterly cruel, in the main.

CLEMENT CRISP: Performances could look pretty… arid, shall we say. There’s no gainsaying that fact.

PETER: People were sniffy about what she did and always I remember mum saying, “It was so important I got to as many people as possible - that’s all I wanted to do, we did it in cinemas, we did it at dog tracks, we did it at Butlins, wherever there was an audience.”

CLEMENT: What was missing I think was glamour. The glamour of the Opera House, Covent Garden, which Mona Inglesby’s company did not have – they were hard-working dancers.

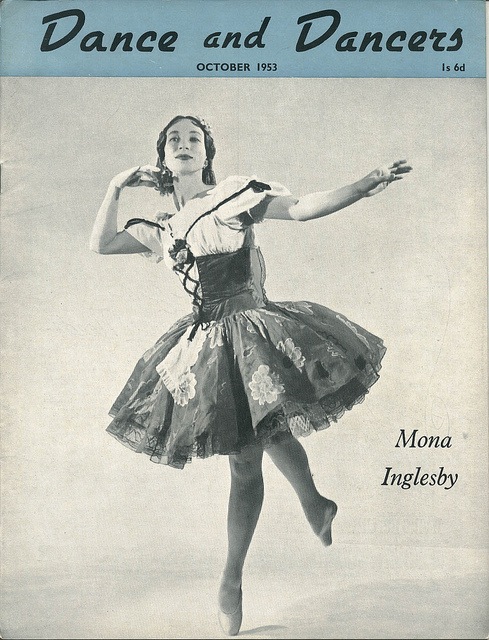

IB: It’s amazing looking at your collection, Peter, I’m just so struck by how big your mother was. There’s a book here - Jewels of the Ballet 1946 - the front-jacket picture is Mona Inglesby. She’s on the cover of Dance and Dancers (see left), she’s in The Tatler, she’s in The Illustrated London News – she was huge then. And yet there’s this amazing, almost total blackout of her name now.

IB: It’s amazing looking at your collection, Peter, I’m just so struck by how big your mother was. There’s a book here - Jewels of the Ballet 1946 - the front-jacket picture is Mona Inglesby. She’s on the cover of Dance and Dancers (see left), she’s in The Tatler, she’s in The Illustrated London News – she was huge then. And yet there’s this amazing, almost total blackout of her name now.

PETER: I never understood it. I saw Mum on the front of mags that clearly mattered at the time. It’s almost as if she’s been expunged from the history books, and I really don’t understand why.

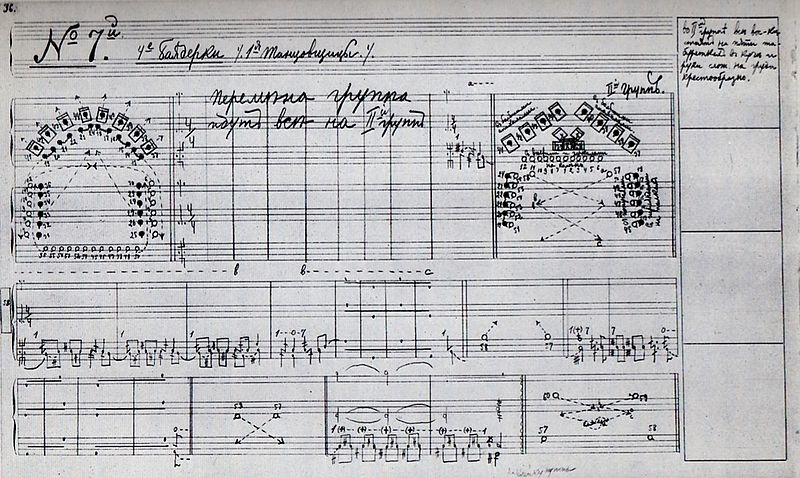

IB: Historically, though, the International Ballet’s productions happened to be unique. Mona’s guiding light was an elderly Russian who’d been the chief balletmaster before the Russian Revolution of the Imperial Ballet in St Petersburg - later to be known as the Kirov Ballet. Nikolai Sergeyev had worked under the legendary choreographer of The Sleeping Beauty, Marius Petipa, recording the choreography of all his ballet productions - the backbone of classical ballet as we know it today. As the Communist revolution erupted in 1917, Sergeyev was desperately afraid the precious Imperial records would be destroyed. He seized the books and fled to Europe. He was welcomed by Sergei Diaghilev in the Ballets Russes and then de Valois at Sadler’s Wells to stage their classical productions. But both of them adapted and modernised the stagings. Tessa Sollom worked under Sergeyev.

TESSA SOLLOM: He left the Sadler’s Wells, as it then was, because he wasn’t given respect. And Mona gave him respect and then he said, "I’m not giving Mona the leads because it’s her running the company. I’m giving them to her because she is really good and is respectful of the classics."

IB: In Mona Inglesby Sergeyev found his acolyte, she wanted to stage these classics exactly as he said they had been under the legendary Petipa.

TESSA : He brought all those notes out under cover in a suitcase - it was quite frightening for him and his wife.

IB: Rhona Cooke and Noel Bronley were both taught by Sergeyev.

RHONA: He had a wonderful rapport. And he used to whistle …..(she demonstrates) Moving his hands for the steps. And you just picked it up.

NOEL: And certainly to see him walk into class with these enormous books. There is this famous story about somebody turning over a few pages behind his back and they said he didn’t notice. But he did! And I was so cross with this boy in the front who tried to hoodwink this old man. But he turned them back, he knew what had been done. There were a lot of people who didn’t like Sergeyev, who complained because he used a stick. Well, he probably tapped your bottom …

RHONA: It was in fun more often than not.

NOEL: And it was in fun – but there were a lot of people who were anti him.

IB: Sergeyev wasn’t the only larger-than-life staff member. Mona’s mother was a constant presence, just as Mona’s father and husband hovered in the background financially. Henry Danton has vivid memories of Mrs Inglesby.

HENRY: She was quite a character. She was not exactly in charge of the costumes, but looking after the costumes. They were extremely expensive, they were beautifully made so Mrs Inglesby was always on top of everyone, you must not sit down, you mustn’t eat in the costume, put it on at the last minute and take it off at the first minute you can, that was her. But she was into everything she was a real ballet mother.

IB: Was that resented by the dancers?

HENRY: Certain of them, yes. Harold Turner, principal dancer, he and Mona didn’t get on at all, and he specially disliked Mrs Inglesby, and I remember one incident on tour - they were having some kind of argument and he had a dressing room with a wooden ladder up to it, and he actually pushed her down the ladder. And she was always so beautifully dressed and she had a bowler hat on which was fashionable at the time and she came down the stairs completely dishevelled! It was marvellous for me because Mona wanted to get rid of him as a partner so I was taken on as her partner. I had so little training I had no idea what I was doing but she was so kind. She was very kind to work with.

IB: Like Moira Shearer, Henry Danton left International Ballet to join Sadler’s Wells, which after the war was seizing the limelight. (He would be in the original cast of Frederick Ashton's 1946 masterpiece Symphonic Variations.) Several companies were now jockeying for top billing, all led by determined women - from the mature and well-connected Ninette de Valois and Marie Rambert down to the young and enthusiastic Mona Inglesby. To get a sense of the dance landscape at the time I spoke to Jane Pritchard, archivist and curator of dance at the Victoria and Albert Museum.

IB: Like Moira Shearer, Henry Danton left International Ballet to join Sadler’s Wells, which after the war was seizing the limelight. (He would be in the original cast of Frederick Ashton's 1946 masterpiece Symphonic Variations.) Several companies were now jockeying for top billing, all led by determined women - from the mature and well-connected Ninette de Valois and Marie Rambert down to the young and enthusiastic Mona Inglesby. To get a sense of the dance landscape at the time I spoke to Jane Pritchard, archivist and curator of dance at the Victoria and Albert Museum.

JANE PRITCHARD: When the war started dance, like other forms of theatre, went slightly cold – what was going to happen? But very quickly dance came to the fore. And whereas little happening in theatre, for dance it’s almost a boom period.

IB: What difference does the IB make to that landscape.

JANE: Well, I think the International Ballet is quite extraordinary because it’s set up without public funding as a touring company, set up to tour and then to come into London, so in a way it’s working the opposite way to many companies. (Right, the 1943 tour list, courtesy Henry Danton)

IB: Was this a pretty much unheard-of model for ballet companies?

JANE: I would say it was.

IB: How would you distinguish the ethos of the International Ballet from the other companies that existed at the time?

JANE: I think one of the extraordinary things about International Ballet was that although they do create their own works, those are probably not the works they’re most associated with. They’re out there touring the full-evening works that presented obvious theatrical spectacle, and they were stories people could easily understand at a time when these were only being seen occasionally by other companies – if at all. I think one of the things about International Ballet is that it is a company that is reaching out to audiences.

[Newsreel voice: “...The scene of their triumph was the great stadium in Zurich, the Hallenstadium, which seats nearly 10,000 people. And here is the company going into rehearsal...”]

IB: That newsreel was about International Ballet’s visit to Zurich in 1951. Two years later they filled the Verona Arena in Italy with 30,000 spectators (their audience pictured above). International Ballet by now was a huge success story, booked up overseas and reaching a far wider British public than any other company. When the Arts Council was set up after the war, its mastermind - the economist John Maynard Keynes, who was married to the Diaghilev ballerina Lydia Lopokova - saw the emerging English ballet as a major player in a new national culture. While London was mainly served by Sadler’s Wells from Covent Garden, International Ballet was the company for nationwide audiences. And it achieved the height of national recognition when the new Royal Festival Hall was opened in 1951 - International was the company chosen for the inaugural season. I asked Mona’s son, Peter, whether his mother had talked about it.

IB: That newsreel was about International Ballet’s visit to Zurich in 1951. Two years later they filled the Verona Arena in Italy with 30,000 spectators (their audience pictured above). International Ballet by now was a huge success story, booked up overseas and reaching a far wider British public than any other company. When the Arts Council was set up after the war, its mastermind - the economist John Maynard Keynes, who was married to the Diaghilev ballerina Lydia Lopokova - saw the emerging English ballet as a major player in a new national culture. While London was mainly served by Sadler’s Wells from Covent Garden, International Ballet was the company for nationwide audiences. And it achieved the height of national recognition when the new Royal Festival Hall was opened in 1951 - International was the company chosen for the inaugural season. I asked Mona’s son, Peter, whether his mother had talked about it.

PETER: I’ve certainly got the programme for the opening night somewhere.

IB: There it is.

PETER: Thank you - 6d for the programme, isn’t that brilliant? She never talked about the Festival Hall as being a privilege. She never talked about it as being anything other than she expected. What she did talk about was that it was a new, new hall, and we were the first to dance in it. I remember her telling me the stage was literally a square and she said I’m not having that so they redesigned it so they could actually dance on it.

IB: Tessa Sollom danced in the first Festival Hall performance. It was a glamorous programme including the great “White Swan” act of Swan Lake and Capriccio Espagnol by Diaghilev’s famous choreographer, and world star of The Red Shoes, Leonide Massine, who worked personally with the company.

TESSA: It’s almost like a dream now. We used to come here rather early and have coffee early before we started the rehearsals.

TESSA: It’s almost like a dream now. We used to come here rather early and have coffee early before we started the rehearsals.

IB: It must have struck you as an amazing building?

TESSA: Oh yes and so huge. We had to have extra rehearsals, Massine v particular, had to be absolutely right.

IB: Leonid Massine was one of the most important Diaghilev choreographers and here he was working with International Ballet. This must have been a most prestigious date?

TESSA: Oh, it certainly was. It was just a fascinating ballet to be in, Capriccio Espagnol, as well as Gaieté Parisienne (pictured, Mona Inglesby as the Gloveseller in Gaieté Parisienne). We had to really practise for that as there was a classical can-can in it - as we call it - with the jumping split down from the top to the bottom. Down you went into the splits.

[MUSIC: Offenbach’s Can Can]

IB: But there were worrying signs. Sadler’s Wells Ballet had been given first dibs in the Arts Council’s share-out with a risky move from their tiny Islington theatre into the large, vacant Royal Opera House - this was a gamble that couldn’t be allowed to fail. And the creative Ballet Rambert had to be rescued too, always on the edge of bankrupcy. International Ballet seemed to be looking after itself rather well. But - shortly before the Festival Hall opening, Mona’s mentor Nikolai Sergeyev died. Mona admitted to me that without him she felt standards slipping. Meanwhile the superstar ballerina Alicia Markova had started her own glamorous touring company, the Festival Ballet, hitting International’s ticket sales. And there was also a critical view that Sergeyev’s Russian-style productions were looking backwards, not keeping up with changing taste.

When in 1953 Mona asked the Arts Council for a small subsidy to cover her first deficit, she was turned down. I asked the archivist Jane Pritchard why that was.

JANE: One thing that strikes me about International Ballet, is that they’re not saying they’re setting up a “British” ballet. So I think they’re taking a different perspective. De Valois with the Vic-Wells/Sadler’s Wells company was setting out to establish a British ballet, so she was turning everything to her own ends, very cannily. She knew what she was doing. But Mona Inglesby was respecting tradition in a stronger, different way.

PETER: Mum would always talk about the Festival Hall as her swansong.

IB: And yet the company went on two more years?

PETER: Always I remember the Festival Hall opening – she loved it, because it was the first time Britain coming out of nasties, there was a genuine air of celebration. She wouldn’t talk about anything after that. Not a thing.

IB: Mona’s husband, Edwin Derrington, who was the company manager, was furious. They had no option but to close. He wrote to The Dancing Times pointing out that they’d only asked for £500 a week subsidy when Sadler’s Wells was getting £3,795 a week for its touring. I showed a copy of Mr Derrington’s letter to Peter.

PETER: It’s the first time I’ve actually seen how he felt and knowing Dad as I did of course I can see the anger - quite coruscating. He said, “The amount of money they would have had to spend in order just to keep us afloat was just minuscule.”

JANE PRITCHARD: Of course there wasn’t even a dance panel on the Arts Council at that time, it was just a sub-branch of music in the way it was funded.

JANE PRITCHARD: Of course there wasn’t even a dance panel on the Arts Council at that time, it was just a sub-branch of music in the way it was funded.

IB: Do you think there was any animus against Mona and the International Ballet?

JANE: I suspect there was actually, I suspect there was a resentment. It was not a company that had the seal of approval. (Inglesby preparing, left, for Act 3 of Swan Lake)

JOHN DOWSON: She kept going all the way through the war on her own resources, bums on seats. The war ends, the Vic Wells people start getting back together and the government starts doling out money to them – never once did she get any funding whatsoever. Totally unfair.

JANE: The Royal Ballet still gets far more than any other dance company, there’s very much a hierarchy.

RHONA COOKE: I can’t imagine how Mona must have felt when it was clear the company had to disband. It must have been awful. But she was very happily married then and she had the joy of expecting their first child.

IB: Mona closed the International Ballet in December 1953. De Valois, Rambert and Alicia Markova would all be made Dames - but Inglesby, who was still only 35, was left by the wayside, without official recognition and less and less visibility in official ballet history. However - she had one last job she felt she had to do.

[MUSIC UNDER: Sleeping Beauty - Fairies’ entrance in Prologue]

When Sergeyev died, his notations of the original ballets were left behind. No one could read them now, but Mona was determined to rescue them, believing them far too precious to be lost. She tried to find a home for them in Britain, but neither the ballet establishment nor dance libraries seemed to give strong enough assurances that they’d preserve them. And besides, ballet had moved on - the classics had been updated all around the world with more technically showy dancing and more modern production styles; so these notations were considered of archaeological interest only.

Eventually, in the 1960s, Mona found a berth for them in Harvard’s Theatre Library in the United States. And there they lay unnoticed, indecipherable, gathering dust for decades. Until the Kirov Ballet in the late 1990s decided to try to sweep away a century of varnishing and changes, and recreate the original Sleeping Beauty of 1890. The American dance historian and professor Tim Scholl takes up the story.

TIM SCHOLL: I was sitting in the office of the Director of the Kirov Ballet’s office one night. We were talking about the Sleeping Beauty problem, and of course Sleeping Beauty is one of the most legendary productions...

IB: ...But much changed in the Soviet period.

TIM: Absolutely. So off the top of my head I said, well, have you thought about using the Sergeyev notations? And he looked at me, and I realised of course most people in Russia didn’t realise those notations existed. We talked about it, and he said okay we’ll go look at them and see if we can actually use them to re-stage.

[MUSIC: Sleeping Beauty - Rose Adagio]

IB: The reconstructed Sleeping Beauty was a triumph, and also a shock - it really did reawaken the classical style out of deep sleep. Arguments continue about it in Russia and in Britain too, where the tradition of modernising is well entrenched - but dance experts have realised that despite their flaws Sergeyev’s volumes are a Rosetta Stone for the ballet art. Through them steps and styles can be rediscovered as their original creators made them. This October Raymonda, the latest recreation, was performed at La Scala, Milan, and even lost ballets are being recovered.

TIM SCHOLL: They’re incredibly valuable. We are so fortunate to still have them, because they left Russia in 1918 in a suitcase.

TIM SCHOLL: They’re incredibly valuable. We are so fortunate to still have them, because they left Russia in 1918 in a suitcase.

JANE PRITCHARD: They are incredibly important documents for understanding dance history. It is our way back into the past, really.

TIM: There’s this notion that cultural patrimony has been stolen from Russia and they should be returned. I would much prefer they remain in the Harvard Theatre Collection than the theatre collection in St Petersburg, these manuscripts really require care that I don’t think they could have in Russia today. (Left, a page of Sergeyev's notation for La Bayadère)

JANE: I do think it’s very sad they went to Harvard rather than staying in Britain and I really do think it was a missed opportunity when they could have found a home in this country and nobody was interested.

IB: Were they wrong?

JANE: I think they were wrong. I think they should have saved them in Britain because although they originate in Russia, they are very much part of a British dance heritage.

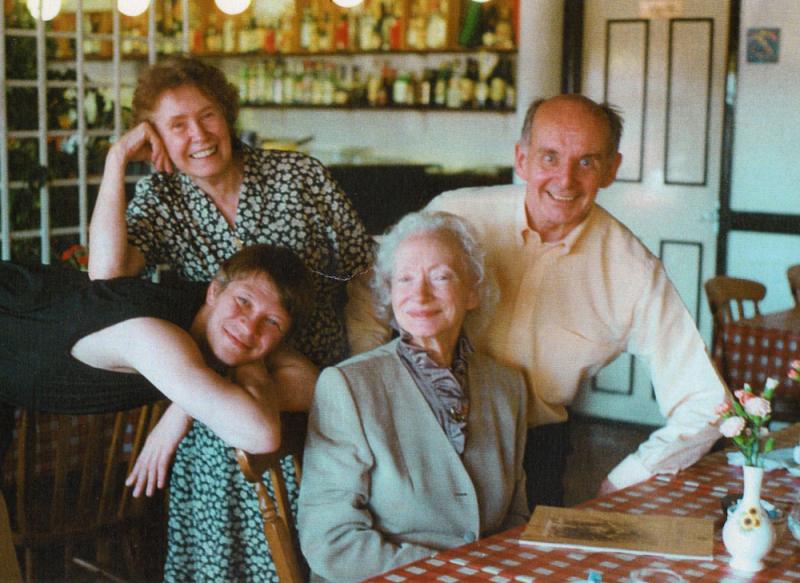

IB: When the Kirov Ballet performed their restored Sleeping Beauty in London in 2000 I put their reconstructing team in touch with Mona, and they went down to see her in Bexhill (pictured right, Mona Inglesby with the Kirov's Sergei Vikharev, IB dancer Audrey Harman and friend Alex Bisset). She was quite overwhelmed, and so were they – they’d no idea that the notations had survived thanks to one doughty English ballerina.

IB: When the Kirov Ballet performed their restored Sleeping Beauty in London in 2000 I put their reconstructing team in touch with Mona, and they went down to see her in Bexhill (pictured right, Mona Inglesby with the Kirov's Sergei Vikharev, IB dancer Audrey Harman and friend Alex Bisset). She was quite overwhelmed, and so were they – they’d no idea that the notations had survived thanks to one doughty English ballerina.

It’s staggering to think that such a crucial resource of world art was only preserved because of two people’s presence of mind: a Russian fugitive and an English dancer. Thank goodness Mona Inglesby knew, just in time, the permanent importance of what she’d done. When I last saw her before she died in 2006, I asked her what she felt about the rebirth of those old notebooks. She said, very quietly, “It took a lot of working out, thinking of the best thing to do. The main thing is that they’re safe, and I’m quite happy with that.”

JOHN DOWSON: She’s been all but forgotten - gone out of people’s consciousness.

IB: How do you assess her place in dance history?

JOHN: Well - totally invaluable. I mean, she brought ballet to the masses.

[CONCLUDING MUSIC: Coppelia, Act 3 pas de deux "La Paix"]

- Between interviewing and transmission of the programme, Moira Tucker and Thelma Clifford died.

- Listen to the Radio 4 documentary on this BBC link

- Buy Ballet in the Blitz: the history of a ballet company, the memoirs of Mona Inglesby with Kay Hunter

See What's On in dance in 2013 in theartsdesk's comprehensive planning calendar

Below, some of the campaigning IB dancers at the Festival Hall plaque celebration: Front, from left: Moira Tucker front left, Rhona Cooke, Tessa Sollom, Patti Bentley; behind, Pauline White, Joyce Lyndon, Thelma Clifford, Simon Zolan, Noel Bronley, Judy Waller and Angela Bayley

Watch some of the final Act of the recreated 1890 Sleeping Beauty at the Mariinsky, in this particular performance more interesting for the period glimpses in costume designs and choreographic variation than for the obliviously modern style of most of the dancing (youtube via MrLopez2681)

Explore topics

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Dance

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

R:Evolution, English National Ballet, Sadler's Wells review - a vibrant survey of ballet in four acts

ENB set the bar high with this mixed bill, but they meet its challenges thrillingly

R:Evolution, English National Ballet, Sadler's Wells review - a vibrant survey of ballet in four acts

ENB set the bar high with this mixed bill, but they meet its challenges thrillingly

Like Water for Chocolate, Royal Ballet review - splendid dancing and sets, but there's too much plot

Christopher Wheeldon's version looks great but is too muddling to connect with fully

Like Water for Chocolate, Royal Ballet review - splendid dancing and sets, but there's too much plot

Christopher Wheeldon's version looks great but is too muddling to connect with fully

iD-Reloaded, Cirque Éloize, Marlowe Theatre, Canterbury review - attitude, energy and invention

A riotous blend of urban dance music, hip hop and contemporary circus

iD-Reloaded, Cirque Éloize, Marlowe Theatre, Canterbury review - attitude, energy and invention

A riotous blend of urban dance music, hip hop and contemporary circus

How to be a Dancer in 72,000 Easy Lessons, Teaċ Daṁsa review - a riveting account of a life in dance

Michael Keegan-Dolan's unique hybrid of physical theatre and comic monologue

How to be a Dancer in 72,000 Easy Lessons, Teaċ Daṁsa review - a riveting account of a life in dance

Michael Keegan-Dolan's unique hybrid of physical theatre and comic monologue

A Single Man, Linbury Theatre review - an anatomy of melancholy, with breaks in the clouds

Ed Watson and Jonathan Goddard are extraordinary in Jonathan Watkins' dance theatre adaptation of Isherwood's novel

A Single Man, Linbury Theatre review - an anatomy of melancholy, with breaks in the clouds

Ed Watson and Jonathan Goddard are extraordinary in Jonathan Watkins' dance theatre adaptation of Isherwood's novel

Peaky Blinders: The Redemption of Thomas Shelby, Rambert, Sadler's Wells review - exciting dancing, if you can see it

Six TV series reduced to 100 minutes' dance time doesn't quite compute

Peaky Blinders: The Redemption of Thomas Shelby, Rambert, Sadler's Wells review - exciting dancing, if you can see it

Six TV series reduced to 100 minutes' dance time doesn't quite compute

Giselle, National Ballet of Japan review - return of a classic, refreshed and impeccably danced

First visit by Miyako Yoshida's company leaves you wanting more

Giselle, National Ballet of Japan review - return of a classic, refreshed and impeccably danced

First visit by Miyako Yoshida's company leaves you wanting more

Quadrophenia, Sadler's Wells review - missed opportunity to give new stage life to a Who classic

The brilliant cast need a tighter score and a stronger narrative

Quadrophenia, Sadler's Wells review - missed opportunity to give new stage life to a Who classic

The brilliant cast need a tighter score and a stronger narrative

The Midnight Bell, Sadler's Wells review - a first reprise for one of Matthew Bourne's most compelling shows to date

The after-hours lives of the sad and lonely are drawn with compassion, originality and skill

The Midnight Bell, Sadler's Wells review - a first reprise for one of Matthew Bourne's most compelling shows to date

The after-hours lives of the sad and lonely are drawn with compassion, originality and skill

Ballet to Broadway: Wheeldon Works, Royal Ballet review - the impressive range and reach of Christopher Wheeldon's craft

The title says it: as dancemaker, as creative magnet, the man clearly works his socks off

Ballet to Broadway: Wheeldon Works, Royal Ballet review - the impressive range and reach of Christopher Wheeldon's craft

The title says it: as dancemaker, as creative magnet, the man clearly works his socks off

The Forsythe Programme, English National Ballet review - brains, beauty and bravura

Once again the veteran choreographer and maverick William Forsythe raises ENB's game

The Forsythe Programme, English National Ballet review - brains, beauty and bravura

Once again the veteran choreographer and maverick William Forsythe raises ENB's game

Comments

Seeing the International

I wholeheartedly agree. The