The great Russian ballerina Maya Plisetskaya, renowned for her deathless Dying Swan and a performing career that lasted more than 60 years, died suddenly of a heart attack at home in Munich at the weekend, aged 89.

To the West she epitomised the Bolshoi ballerina in style, fierily expressive, virtuosic, larger than life, but she was also an unclassifiable individualist who challenged Soviet norms.

Her longevity was legendary. Dismissed from the Bolshoi aged 65, she simply carried on dancing on pointe, even longer than the tireless Margot Fonteyn and her Cuban counterpart, Alicia Alonso (who at 93 is now the last of the divas from that extraordinary era).

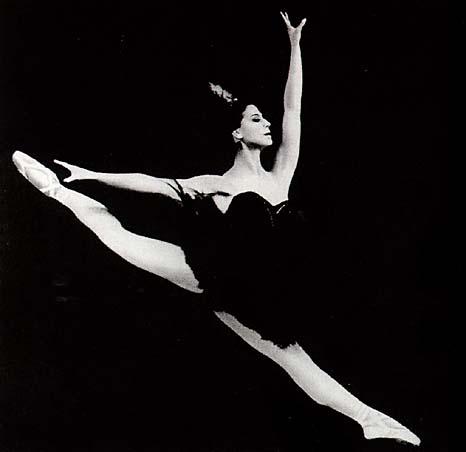

Like Callas, Plisetskaya deployed her passionate personality and charisma to conquer audiences, and to disguise a less than ideally refined technique. Her jumps were phenomenal – like men’s jumps, people said. And she perfected a sinuous pliancy in her back and arms that was part natural flexibility, but part a clear decision that this was one of her artistic weapons.

Though the Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev described her as the best ballerina in the world, she only won the status of international star through years of persecution and monitoring. The KGB even put a microphone in her bed.

As a girl she watched as her father was marched off in Stalin's Terror to what she eventually discovered was execution, and her pregnant mother to the gulag. Treated as a potential traitor by the KGB, due to her family history and her flippancy about politics, Plisetskaya learned to turn her individualism into an artistic calling card, magnetising her audiences.

She was famously banned from the Bolshoi's Western debut in London in 1956, but it caused so many international protests that Khrushchev reassessed her value to the Soviet propaganda machine abroad. By the time she was allowed to travel abroad, appearing in the US in 1959 and the UK in 1963, Plisetskaya was in her mid-thirties and acknowledged as the Bolshoi’s prima ballerina, stamping the theatre with her red-headed brand of drama and athletic excitement.

Plisetskaya’s thumbprint remains all over Bolshoi ballerina lore, as both dancer and dissident artist

Her antipathy to the new Bolshoi chief Yuri Grigorovich, slightly her junior, turned into a battle for power between them. Plisetskaya established her own group of performers and sought new choreography from other dance-makers, most famously the Carmen Suite from Cuban choreographer Alberto Alonso. (The ballet was also staged in Havana for Alicia Alonso – partnered by Plisetskaya’s brother, Azary Plisetsky.)

You can get a true sense of this exciting, indomitable woman from her autobiography, I, Maya Plisetskaya, which she wrote herself in characteristically forthright, dramatic style. (I reviewed it in 2001.) She makes plain why she refused to defect, despite provocations; it boiled down to the instilled fear for her family's lives, her love of the Bolshoi Theatre, and her determination not to give in to a bad temporary version of an eternal Russia.

Her dancing is well represented on Youtube. Here she is in the firecracker role of Kitri in Petipa’s Don Quixote back in 1954 (the Lenfilm compilation dates from 1959). From the very start of this extract you see the ballon – the impression of hovering in the air for a nano-second mid-jump – that Plisetskaya claimed to have taught herself. She wrote in her autobiography about trying it out as an 18-year-old Bolshoi newbie in Chopiniana, noticing the effect of “this little trick” on the audience.

You can see the part played by her exceptionally pliable back. When she throws herself into the air, she arches backwards, her head exultantly raised to the sky – the effect is of release from gravity. She is partnered here by Yuri Kondratov.

Plisetskaya lost out on that first Western tour to the Bolshoi's senior ballerina Galina Ulanova, by then the moonlit queen of ethereal heartbreak. But within the USSR the two were being obsessively paired in contrasting roles by the then Bolshoi ballet director Leonid Lavrovsky. When Ulanova danced Giselle, reported Plisetskaya, she herself was always delightedly cast as the hard, mysterious Myrtha, Queen of the Wilis. To play Giselle was not for her.

The two were famously filmed in 1953 in the colourful romance The Fountain of Bakhchisarai, choreographed by Zakharov in 1934, with Ulanova as the gentle Polish princess kidnapped by Khan Girey and Plisetskaya as his passionate, jealous harem favourite determined not to lose him to a European woman. In this medley, the opening with a coquettish Ulanova is followed by Plisetskaya, undulating in very provocative harem outfit, from 4:07, with a series of her characteristically astounding jumps from 5:15. The final section as the two women face off is almost all melodramatic histrionics, until the exquisite miracle of Ulanova's death scene.

In 1966 Plisetskaya used all her clout at the Bolshoi to bypass Grigorovich and the narrow typecasting he offered her, to commission a new ballet from the Cuban choreographer Alberto Alonso, Carmen Suite, to music by her husband, the leading composer Rodion Shchedrin. Mounting so sexually contemporary a ballet proved a struggle: her autobiography has a chapter devoted to the full, high-wire story. Once Plisetskaya won her battle, she performed her Carmen some 350 times, she reckoned, the final time in 1990 (when she was 65).

Here is a 1973 film extract from early in the drama when Carmen haughtily seduces Don José, danced by Nikolai Fadeyechev (“I loved to dance with him because our personalities complemented each other’s. It was impossible to disturb his equilibrium,” she wrote). Though this is risible choreography Plisetskaya invests it with dark, sexy hauteur.

In middle age, strong as a horse, fêted worldwide, Plisetskaya was chafing at the narrowness of her Bolshoi repertoire where Grigorovich had effectively locked down the schedule. Now permitted a long leash by the Brezhnev government, she looked to France’s choreographers, Roland Petit and Maurice Béjart, both fans of diva qualities in a ballerina. She petitioned Béjart to let her dance his Boléro when she was 50.

Here she is in the work with his company, the Ballet of the 20th Century. The restrained opening shows those renowned arms, the fine wrists and hands. You could read all sorts of things into the set-up, the circle of men and the woman on the table, but Plisetskaya herself always rejected having “subtexts” read into her dancing. Boléro is a piece of schlock, both the music and choreographic concept, and Plisetskaya, for all her Cecil B de Mille moviestar glamour, doesn't always look certain of the steps. But from around 13:10 she starts to radiate happiness, a party girl letting her hair down. The applause occupies nearly a quarter of the film.

But despite these forays into the outside world, it was in swan feathers that Plisetskaya's legend is fixed in aspic. Many other ballerinas were more delicate Odettes, but what Plisetskaya did with the role was sombre, musical and strong; her Odile was dazzling and uncomplicatedly evil. She danced Swan Lake 800 times, she said, far too many of them being wheeled on at government banquets for visiting heads of state, heedless of production values. "It is maybe the best ballet ever created. And I want to pull my hair out and stuff it down the directorate’s throat – that’s what they’ve done to me," she told Valery Panov.

Her Dying Swan became even more legendary, partly because it just would not die. She would rise during the audience's ovation and agree to die all over again. The Trocks made one of their most treasured parody numbers in honour of Plisetskaya's inextinguishable swan.

Yet here is a spellbinding little film made when she was in her twenties, and her Dying Swan was new and the emotions fresh. The opening shows her watching swans which morphs into her dancing at around 1:45. One sees what a sumptuous natural lyricism the young Plisetskaya possessed, before the battles hardened her. There are technical secrets to be learned there in the way those relatively plump arms evoke the ripple of water and those toes discreetly patter, but there's no technical explanation for the poignancy in her face and breast as she yearns to escape the gathering weakness.

Maya Plisetskaya, born 20 November 1925, died 2 May 2015.

Add comment