There was not likely to be much ballet here, despite the Pet Shop Boys’ proud use of the word to distinguish their substantial three-act score. This delivers a richly James Bond-ish ride through big pop tunes, opulent filmic moments and some nice bumps between fantasy scene-setting and camp nightclubbing. It was the two musicians who thought up the idea of turning Hans Christian Andersen’s very beautiful and poignant 1897 fairytale into a ballet, a story in which the deliberate destruction of an astonishing, ingenious clock is not the end of the story, but becomes a celebration of creativity itself.

To deliver the story de Frutos and his designers, Katrina Lindsay and Tal Rosner, conjure a place of (literally) smoke and mirrors that appears to relate to the Soviet Twenties, a mechanistic world from which the bad guy Karl emerges, incarnated very handsomely by Ivan Putrov, formerly of the Royal Ballet, and here showing an evil streak he was denied in classical roles. He was an instigator of this enterprise, and I guess might have hoped it would do for him what Matthew Bourne’s Swan Lake did for Adam Cooper, but at this early stage this production is too inconsistent for that.

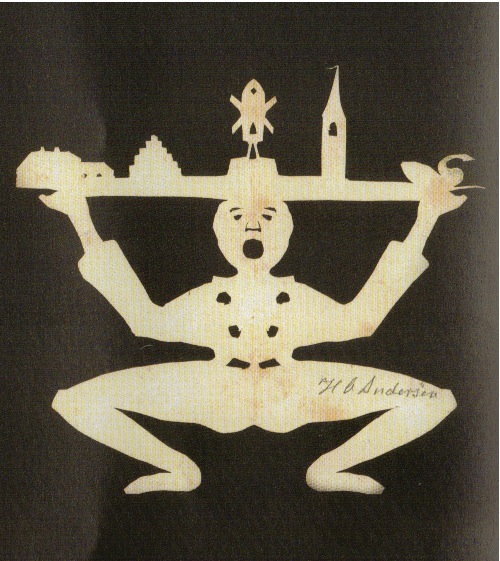

The story adapts very well to three acts in Matthew Dunster's scenario. Act I introduces the four main characters, the chess-man King and his daughter, whom he proposes to give away in marriage to the creator of “the most incredible thing”, and the two rivals for her hand, the poor inventor, chopping out delicate paper shapes with huge scissors (as Hans Andersen loved to do, pictured left an example at Odense Museums), and the rotter, a Sovietique beast who walks like a robot and treats all his collective minions like robots. At a very silly talent show a garrulous hostess introduces contenders for the Royal competition, like the opening rounds of Britain’s Got Talent (one of them says he can turn a towel into a swan - “rather like Jesus turning water into wine”, quips the hostess sarcastically. “But this is still a towel.”)

The story adapts very well to three acts in Matthew Dunster's scenario. Act I introduces the four main characters, the chess-man King and his daughter, whom he proposes to give away in marriage to the creator of “the most incredible thing”, and the two rivals for her hand, the poor inventor, chopping out delicate paper shapes with huge scissors (as Hans Andersen loved to do, pictured left an example at Odense Museums), and the rotter, a Sovietique beast who walks like a robot and treats all his collective minions like robots. At a very silly talent show a garrulous hostess introduces contenders for the Royal competition, like the opening rounds of Britain’s Got Talent (one of them says he can turn a towel into a swan - “rather like Jesus turning water into wine”, quips the hostess sarcastically. “But this is still a towel.”)

Act II is, at a very far remove, a “white” act from 19th-century ballet, an abstract fantasy, dominated by video and kaleidoscopic lighting as the inventor’s clock unveils its marvels, and the bad man smashes it and wins the competition, since destruction is as incredible as the construction. Act III shows the Princess’s wedding to the villain being upended by the clock’s revenge, and a happy-ever-after wedding and epilogue.

Those are bones which demand from de Frutos some emotional/character flesh in Acts I and III and abstract dance flesh in Act II. He does better with character incident, notably in a duet for the King and his anguished daughter, and in a protesting encounter between her and Karl that picks up some strong eroticism from the chemistry between the outstanding Clemmie Sveaas and Putrov (pictured below, © Hugo Glendinning).

In both those duets I feel de Frutos’s own heart and imagination racing, but the romantic duets for the Princess and the inventor, Leo (as in da Vinci), lack similar credibility. Dance in-jokes about Balanchine’s Apollo (the three girls in white tunics) and Nijinska’s Les Noces (the scared bride and her companions piling their heads up) would be cleverer if not repeated, and it is a very post-post-modern smartiepants whose range of jokes extends to contemporaries like Matthew Bourne and Mark Morris.

In both those duets I feel de Frutos’s own heart and imagination racing, but the romantic duets for the Princess and the inventor, Leo (as in da Vinci), lack similar credibility. Dance in-jokes about Balanchine’s Apollo (the three girls in white tunics) and Nijinska’s Les Noces (the scared bride and her companions piling their heads up) would be cleverer if not repeated, and it is a very post-post-modern smartiepants whose range of jokes extends to contemporaries like Matthew Bourne and Mark Morris.

But a three-acter is mercilessly exposing even of first-class choreographers, and de Frutos has picked a dance style for this that's mostly decorous to the point of boring, despite Sveaas's remarkable expressiveness. He has also done nightclub choreography more originally before than he does here. Act II is a curate's egg of all-dominant video and scenery, rollercoaster big music, hit-and-miss direction and cabaret dance for divertissements that limp rather tiredly behind.

Katrina Lindsay’s stunning set design packs a knock-out punch, shards of mirrors, wallpaper of tumbling biplanes over little Soviet housing collectives, the fantastically intricate paper-cut chandelier that pays homage to Andersen's cut-outs, all of this lit with dazzling atmospherics by Lucy Carter. Tal Rosner’s video supplies a very funny quasi-satellite link to the judges of the “incredible” contest, one of whom is the extremely veteran Diana Payne-Myers, grinning like a crone and grabbing for the sponsors’ vodka bottles. More critically, Rosner creates the magical clock with projections of Constructivism-inspired shapes and mindboggling colour sequences that still somehow don’t entirely generate the Clockwork Orange brainwashing effect to the degree it might.

For a first three-act show - which is a huge undertaking for so many first-timers - The Most Incredible Thing is an assemblage of many good ingredients. It’s a ton better than Shoes, thank goodness, though not yet coherent enough to deliver its fairytale without you being extremely aware of the kitchen story - and that means, pace Neil Tennant, the magic isn’t there.

- Buy tickets for The Most Incredible Thing, at Sadler's Wells till Saturday

- Find the Pet Shop Boys' The Most Incredible Thing album on Amazon

- See what's on at Sadler's Wells. Read Sadler's Wells show reviews

- Read theartsdesk Q&A with Javier de Frutos

A Pet Shop Boys' own orchestral compilation

Add comment