Time is a rare privilege in a choreographer’s career - in Britain, anyway. We don’t have the equivalents of Merce Cunningham, Martha Graham or Paul Taylor, who build careers into their eighties and beyond, with mighty efforts from private patrons and friendly art giants of their generation (Andy Warhol, Robert Rauschenberg, Isamu Noguchi et al). UK choreographers are fortunate to get 10 years until the Arts Council deems it time to push them out of the subsidised nest, to vanish in their late thirties, most of them.

Hence the interesting anomaly of Richard Alston, who stands out as the senior figure of contemporary dance with 40 years of almost unbroken career behind him, something to celebrate with a retrospective this week at The Place, his home base for 17 years. The Place was where British contemporary dance began over half a century ago, when a man with no legs and pockets as deep as his passion for dance struck a match to the beginnings of a bonfire. He was the philanthropist Robin Howard, and his name is memorialised on the small theatre inside the former Drill Hall for the Artists Rifles in a Dickensian little sidestreet off Euston Road, now known as The Place, the cradle of British contemporary dance.

Howard sold his possessions and books to buy the premises in the 1970s, primarily to ensure that modern dance could always be renewed by impoverished but outstanding young talents trained up there. Alston, in the late Sixties and early Seventies, was one of those alumni, an unhappy boy from Eton College who went to art college and discovered ballet and Martha Graham.

The retrospective shows us that he was always careful, always graceful, always classically musical, and never a risk-taker

This history is all germane to the show that opened last night, a Dance Umbrella retrospective of Alston, tying his earliest work to his latest. It shows us that he was always careful, always graceful, always classically musical, and never a risk-taker. These qualities have bobbed up and down in his work, as I’ve watched it for a couple of decades, and I appreciate the real virtues while sometimes (well, quite often) wishing that it were more épatant.

A medley drawn from his youthful pieces, Early Days, shows the young Alston sculpting and grooming his poses with self-conscious but natural grace, not a protean imaginer of dance steps, but one able to tailor a line or an effect in a pleasing way, the body of the performer always in equal balance to right and to left, as if it had just returned from the chiropractor.

The chain of little extracts opens with a welcome surprise, a girl spinning with a very long metal pole balanced on her shoulder while a Japanese flute plays - it is exceptionally simple, exceptionally telling, almost a modern Syrinx.

Other samples display carefully constructed jokes, with a Gertrude Stein commentary, "Something to Do", and a score of voices making rhythmic percussion from the words “Rainbow bandit (chug-chug-chug BOOM)”. Whether fast or slow it is always lithe, poised dancing and you can see how Alston prospered in an age where British students must all have been trying to imitate Merce Cunningham. His conservatism, in a sense, was his USP, his balletic sense of line. Alston’s longevity may lie in the fact that he’s not modern at all, he’s always been intent on passing on classical values.

In the past I’ve felt Alston tended to hire reverent dancers rather than individual ones, but this current crop mostly look at ease with being themselves. Nancy Nerantzi is lovely in the swiftly swirling solo Nowhere Slowly (1970), timing the end of each phrase with a sure rubato that momentarily hovers, like a pendulum pausing between swings. It looks strangely like a herald of Frederick Ashton’s 1975 Five Isadora Waltzes. Nerantzi gets inside the poised skin of the Alston style and unleashes her own spirit in the way that I wish I'd seen more of among his docile acolytes over the years (Samantha Smith and Jonathan Goddard were two rare sparks whom I fondly remember). In a solo from the once spectacularly designed Wildlife (1984) Anneli Binder is less of her own woman than Nerantzi, more of the good student.

Liam Riddick is another youngster with that wilful artistry. He leads off in Alston’s brand-new Unfinished Business, a clever opposition of one man to two male-female couples that shows this Welsh 22-year-old as an exceptional new talent. He leaps with a gazelle's eagerness in clean-cut split jumps, he has zest and watchfulness as well as economy. He also has the supreme assistance of a beautiful score, Mozart’s sonata K533, played by a true musician, Jason Ridgway. All the dancers look sprung and attentive to the delightfully warm qualities of Ridgway’s playing.

Emil Gilels plays Mozart's sonata K533, first movement

Alston’s good and less good influences - his musicality, his didacticism - are shown in Martin Lawrance’s po-faced school-of-his-master creation, a short new duet called Other Than I, for a woman and her double. A countertenor warbles Couperin with mellifluous unconcern while the dual dance unfolds with disconnected urgency, sending the girls tumbling to the floor and swiftly recovering. It seems to want to be emotional, but it is self-aware, over-practised, a work that hasn't left the studio for the theatre.

I got echoes of Robbins’s West Side Story, the confrontations between Sharks and Jets

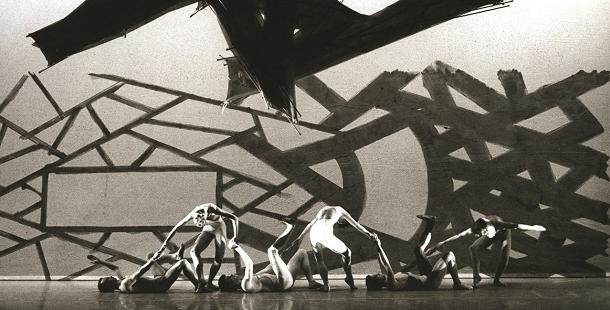

What was missing in Lawrance and Alston last night, to my mind, was shown in the fine central homage the programme pays to Robert Cohan, the original choreographer-director of The Place, now 86 (and present last night). Cohan’s superb directorial qualities shouldn’t obscure what a sharply characterful choreographer he could be, and In Memory (created for London Contemporary Dance Theatre in 1989) is loaded with a dynamically individualised humanity among his six characters that makes it still rewarding to watch.

Characters is the word, because Cohan mines the differences between people’s temperament to drive his use of his modern idiom which is refreshingly direct and athletic. Four men seem in wary rivalry, they grapple, fall against each other, gesture in self-protection - I got echoes of Robbins’s West Side Story, the confrontations between Sharks and Jets. Two of the men are locked in intense dependency, the other two each have an encounter with a woman, neither of them happily fulfilled in emotions, but all furnishing some dynamic and unusual lifts and formations that leave you curious.

For this resurrection, Cohan substituted the original Henze music with Hindemith’s Fifth Viola Sonata, which I dearly wished had found a better player of its uningratiating double stops and oddly disturbing tonalities than Alistair Scahill. But Alston’s dancers are choice individuals, especially a couple of the new young ones, and it looks as if there’s plenty of creative life still to come from the sexuagenarian.

- Richard Alston Dance Company is at the Robin Howard Dance Theatre, The Place, London till Saturday; Hall for Cornwall, Truro, 25-26 Oct; the Fall for Dance Festival, New York City Center, 29-30 Oct; Taliesin Arts Centre, Swansea, 3 Nov; Brighton Dome, 8-9 Nov; Everyman Theatre, Cheltenham, 15 Nov; Festival Theatre, Edinburgh, 22 Nov - all UK tour dates & information

- Dance Umbrella 2011 continues until 29 October

- Other Dance Umbrella reviews on theartsdesk

Add comment