Ever since Diaghilev’s day the relationship of dance movement to its visual design has been a lively, sometimes combative affair. Sometimes people leave whistling the set, saying shame about the dance; other times they hate the set, love the dance. As with the relationship of dance to music, the fit of look to movement can be decisive in why a new ballet escapes the curse of ephemerality and becomes a firm memory that people wish to revisit. It directs the audience how to read it.

There’s another difficulty for the dance designer: classical audiences go to familiar ballets with familiar images in their heads. Should the “look” feed known expectations or create a new landscape for a re-imagining of those familiar feelings and images? Yolanda Sonnabend, who died aged 80 last Monday, tended to the latter, a major theatrical artist whose close collaboration with Kenneth MacMillan on what she called his “neurotic ballets” – the tricky psychological one-acters – gave the visual clues to how to read them.

She had an exceptional emotional hinterland to offer to the public imagination. Rhodesian-born, she was the younger child of European Jewish parents – her father German, her mother Russian – who had met and married as students in Italy in the 1920s. Rising antisemitism drove them, like many other European Jews, to southern Africa in 1930, where her father, an anthropologist, and her physician mother became prominent in a fast-growing diaspora of Jewish intellectuals in Bulawayo. Sonnabend lost her mother to breast cancer when she was 11, and her aunt, also a doctor, raised her and her brother when her father became a professor at Johannesburg's University of the Witwatersrand.

Yolanda was one of the truly great theatre designers of the 20th century

Moving to Geneva following the election of the 1948 pro-apartheid National Party government in South Africa, the Sonnabends were typical of many cultivated Jewish emigrant families who soaked up music, theatre and art along with science and humanistic ideas from their varied backgrounds and travels. (Her brother is the eminent AIDS physician, Dr Joseph Sonnabend.)

Sonnabend became an art student aged 19 at London's Slade School of Fine Art under Nicholas Georgiadis, thanks to whom she had her first break in designing for ballet, Peter Wright’s A Blue Rose for Sadler’s Wells in 1957.

Her first MacMillan design was Symphony, in 1963, and she soon became one of his two favourite designers. The rising choreographer depended on the historically aware Georgiadis for his narrative ballets, Romeo and Juliet, Manon, Mayerling, The Prince of the Pagodas, and the masterly Sixties one-acters The Invitation and Las Hermanas.

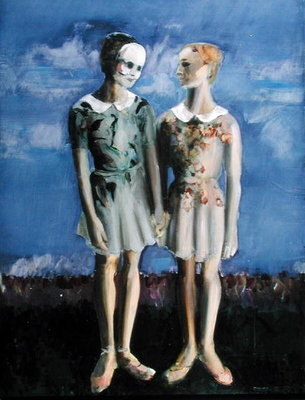

But for his more abstract works increasingly he looked to Sonnabend's painterly ability to create suggestive moods and subconscious associations, which exploited the fantasy and obscurities of his 1970s creations when he was directing the Royal Ballet. These included the Japanese-themed Rituals, the celestial elegy Requiem, the claustrophobic My Brother, My Sisters (right, one of her costume sketches), Playground and Valley of Shadows, and the problematic Wozzeck drama Different Drummer, in which MacMillan had a last-minute change of mind about Sonnabend’s scenery, to her great distress.

But for his more abstract works increasingly he looked to Sonnabend's painterly ability to create suggestive moods and subconscious associations, which exploited the fantasy and obscurities of his 1970s creations when he was directing the Royal Ballet. These included the Japanese-themed Rituals, the celestial elegy Requiem, the claustrophobic My Brother, My Sisters (right, one of her costume sketches), Playground and Valley of Shadows, and the problematic Wozzeck drama Different Drummer, in which MacMillan had a last-minute change of mind about Sonnabend’s scenery, to her great distress.

Those one-acters are infrequently performed today and Sonnabend's distinction in expressionist contemporary ballet design may soon be forgotten, though many of her design sketches and paintings have been collected by the V&A. Her legacy as a painter is largely noted by her portraiture. Nine of her portraits hang in the National Portrait Gallery, including Kenneth MacMillan, Steven Berkoff and Stephen Hawking – whose portrait she painted three times. She herself was the sitter in three NPG portraits (main image).

She has, though, left a definite mark for today's audiences on those most testing of design challenges, the major classical ballets – Swan Lake and La Bayadère at the Royal Ballet, The Nutcracker and Romeo and Juliet at K Ballet, in which her lavish imagination could be controversial. Nowhere more so than in her opulent, gothic Swan Lake for Covent Garden in Dowell’s production, which has divided viewers ever since it premiered in 1987 – it was performed for the last time last season. (Pictured below, Act III, from the Royal Ballet's DVD.)

Paying tribute to Sonnabend, Dowell said: "Yolanda’s designs for my production of Swan Lake broke the traditional mould and took the ballet visually to new heights. In my opinion, her designs made the production totally unique. Working with her was an incredible and pleasurable experience for me. I shall miss her very much."

Paying tribute to Sonnabend, Dowell said: "Yolanda’s designs for my production of Swan Lake broke the traditional mould and took the ballet visually to new heights. In my opinion, her designs made the production totally unique. Working with her was an incredible and pleasurable experience for me. I shall miss her very much."

MacMillan’s widow Deborah said, "Yolanda was one of the truly great theatre designers of the 20th century. Her work with choreographers was inventive, atmospheric and inspired. The fact that Kenneth asked her to design so many of his ballets was testament to his faith in her talent. She always provided an extraordinary part of his creative process."

In 2006 I met the designer in her extraordinary North London house, a picturesque cabinet of curiosities, part-built sets, dolls, masks, materials and objects that nourished her fervid imagination. She spoke about her craft with the clarity and focus that made her a sought-after teacher in all the major art schools.

Good ballet design should have what great art has, and that is 'shock'. It should slightly change you to see it

ISMENE BROWN: What is most important in dance design?

YOLANDA SONNABEND: Design is not decoration – decoration is something added on. Design is visualisation of emotion, so that the dancers' bodies illuminate and add to the drama. It's also about beauty, showing something that people haven't seen before. Good ballet design should have what great art has, and that is "shock". Diaghilev said, "Etonne-moi!" [surprise me!] It should slightly change you to see it, make you say, oh, I didn't expect that, how beautiful.

How do you work when you are creating a new ballet?

It's a very strange and intimate thing a designer has with a choreographer. It's like the portrait-painter and the sitter, an intuitive thing needs to happen. You give each other a kind of power. The choreographer uses you, because you have a different way of seeing. Sometimes he doesn't know what he wants to see, but because it takes time to find what's the right way to go, then draw the plans and make the models, you have to do it weeks ahead of the choreography. I always do hundreds of drawings while I'm finding my way.

Your information comes from the music, above all, and any literary source or visual reference the choreographer's given you. It should be a close collaboration – I don't like to do it by e-mail because we're dealing with 3-D space here. Sometimes, though, you haven't that much choice. When I did L'Invitation au voyage for Michael Corder (1982), he was in America while I was working on it, so I had to just do it around the Duparc music and Baudelaire's poems and tell him when he got back, "Here's the design, like it or lump it."

Do designers ever lead choreographers?

In Nutcracker of course it does, because there's no story and the design has to do everything. And the producer can almost never make up his mind, while you bring him 10 different schemes. Doing it for Teddy Kumakawa (K Ballet, 2005) I was being driven mad because he just couldn't decide, and it's the designer who's got to sort it all out and it had to be so spectacular. Nutcracker is a killer.

'Swan Lake' and 'Giselle' are a piece of cake. 'Nutcracker' and 'Sleeping Beauty' are the hardest. 'Nutcracker' is a killer

You can also have quite a bit of influence on the choreography through the floor plan and where the entrances and exits go, which affects the passage of the dance that the choreographer is making. You can do a fast scene-change that changes the story, or use a costume in a dramatic effect to help choreography. And it was I who suggested to Kenneth, when they come in at the beginning of Requiem, that when the dancers come on shaking their fists they should open their mouths.

What are the main design challenges in the classics?

There are big magic moments in all the classics. Swan Lake and Giselle are a piece of cake. Beauty and Nutcracker are the hardest – Beauty because there's so much of it, Nutcracker because with this notoriously imprecise and variable story it's a nightmare getting the producer to decide what his storyline is. In Beauty the Awakening is everything – it's the beginning of maturity, it's the rising of the sun, if that falls flat it drags the whole long ballet down.

I remember [the critic] Bryan Robertson telling me, when I was starting Swan Lake for the Royal Ballet, that the ending must be wonderful because it's what the public take away with them. I told Maria Bjørnson, when she was doing the 1990s Beauty, always start at the end and work backwards. (Pictured left, Sonnabend's portrait of Maria Bjørnson, mariabjornson.info.) That's what I did with Swan Lake - the last vision is the most important. You must see beauty.

I remember [the critic] Bryan Robertson telling me, when I was starting Swan Lake for the Royal Ballet, that the ending must be wonderful because it's what the public take away with them. I told Maria Bjørnson, when she was doing the 1990s Beauty, always start at the end and work backwards. (Pictured left, Sonnabend's portrait of Maria Bjørnson, mariabjornson.info.) That's what I did with Swan Lake - the last vision is the most important. You must see beauty.

You are above all a painter – is that important?

Yes, I think so. You have to focus onto the dancers, of course, but you have painting to help you with that – colour, line and mass. The way materials can move, different weights – chiffon moves differently from georgette, which is different from silk. You can use that, one moving in circles, another in spirals.

What are the frustrations in the job?

For Anthony Dowell's Swan Lake, I spent ages trying to convince him that the boat at the end should have reins to heaven, like tiny bubbles drawing Odette and Siegfried up into heaven, but when we first tried them they wobbled a bit and Dowell just said no. I'm sure I could have fixed that. I think we had the reins to heaven for one performance, and I spent a long time fighting to get them back but didn't succeed. (Below, the final tableau of Swan Lake, picture grab from the Royal Ballet DVD.)

How do you get on with the dancers?

How do you get on with the dancers?

Dancers always want to look good, above all. I remember I had a lot of bottom trouble. Ninette [de Valois] used to hate to see men's bottoms and I remember with Rituals, my Japanese ballet with Kenneth, there was a bum problem with the sumo wrestlers. But I had to cover them up with this and that. Men now show their bottoms in all their classic costumes – in Diaghilev's time they usually wore breeches and more decorated costumes. I don't like seeing too much of women's bums, which modern costumes do a lot; it's not a nice part of a woman, but you get them now.

Choreographers worry now about costumes distracting from their choreography, rather than adding something to it. Materials have their own movement, different textures, different weights, which people used to use. Ballet now is about body sculpture, which doesn't leave much room for messing about around the body with materials. I did so many of Kenneth's neurotic ballets, and I must say it was a joy to turn from all his damaged children to La Bayadère, where it could all just be pretty. (Pictured below, Sergei Polunin and the Royal Ballet in Sonnabend's costumes in La Bayadère, photo Bill Cooper/ROH, 2008)

You came out of a golden time, when designers were extremely influential in forming the audience's impression of a new dance work. Where are your successors?

You came out of a golden time, when designers were extremely influential in forming the audience's impression of a new dance work. Where are your successors?

There isn't much interest among choreographers now in using stories and drama. They just want a mood to put their body sculpture in, because it's now all about the extraordinary way dancers move, about athletic pyrotechnics. You've got to see that leg angle in relation to the other leg, or a foot hooking around a neck, and materials would be interfering.

I've got so bored seeing all this video and computer stuff they use now. Younger designers seem to be cut off from history, they've never heard of the proscenium theatre, it's Camden Lock, or these small stages, or something site-specific, and they have no idea of the possibilities of flying, or changing scenery in a flash. So they have difficulty reinterpreting classics. For those you have to go to the old masters. Though I do admire some of what they're doing with just light now.

It's a shame that in costumes glamour and fantasy has migrated almost completely over to the catwalk – Chanel used to do ballets, Alexander McQueen and John Galliano could, I'm sure.

Presumably Diaghilev is still the greatest, in terms of the way he put design at the high table of dance – sometimes he even made his designers more of a draw than the choreography.

Most of those ballets of his you just couldn't improve, I wouldn't redesign any of them. Think of Petrushka, Les Noces, Jeux, L'Après-midi d'un faune. Artistic directors everywhere now are visually blind – they have almost no outside knowledge. But I admire Mark Baldwin at Rambert – he paints quite well himself, and he's very interested in the visual side.

What are the things that catch your eye now?

Japanese Manga comics are wonderful – I'd love to do a Manga Nutcracker.

Below, Sonnabend's celestial designs for MacMillan's Requiem (photo Tristram Kenton/ROH)

Add comment