theartsdesk Q&A: David Morrissey on (among other things) the return of 'Sherwood' and 'Daddy Issues' | reviews, news & interviews

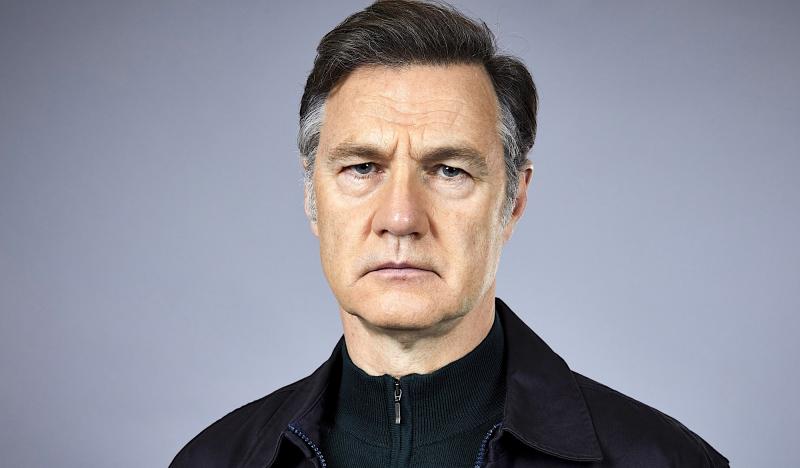

theartsdesk Q&A: David Morrissey on (among other things) the return of 'Sherwood' and 'Daddy Issues'

theartsdesk Q&A: David Morrissey on (among other things) the return of 'Sherwood' and 'Daddy Issues'

Liverpool-born actor reflects on a journey from Everyman Theatre to film and TV stardom

Without ever getting embroiled in tabloid mayhem, even if he has confessed that he’d like to have a go on Strictly, David Morrissey has patiently turned himself into a quiet superstar.

Having cut his acting teeth as a teenager at the Everyman Theatre in his home town of Liverpool (where he was born in June 1964), Morrissey has amassed a huge list of credits on stage and in TV and film, and if you can judge an actor by the writers, directors and fellow-thesps he’s worked with, Morrissey has achieved triple-A status. Mind you, one of his proudest achievements was being invited by his beloved Liverpool FC to do the voice-over for the official Anfield stadium tour.

He made Captain Corelli’s Mandolin (1994) with director John Madden, played the Duke of Norfolk in The Other Boleyn Girl (scripted by Peter Morgan), appeared in Sam Taylor-Wood’s story of the teenage John Lennon, Nowhere Boy, and joined a high-octane British cast (not least the indestructible Jason Statham) in Elliott Lester’s thriller Blitz. In 2006, he somewhat implausibly starred opposite Sharon Stone in Basic Instinct 2 (pictured below), which he would freely acknowledge didn’t achieve quite the seismic impact of the 1992 original.

But it’s on TV that Morrissey has left his most indelible mark, and he has starred in several of the most acclaimed dramas in recent memory. He starred in Danny Brocklehurst’s BBC One drama The Driver, played MP Stephen Collins in Paul Abbott’s political thriller State of Play, and turned himself into Gordon Brown opposite Michael Sheen’s Tony Blair in The Deal, written by Peter Morgan and directed by Stephen Frears (the latter piece bagged lifelong Labour supporter Morrissey a Best Actor award from the Royal Television Society). Other major credits included Red Riding, South Riding, The Missing, Thorne, and the role of unsmiling Roman general Aulus Plautius in the Butterworth brothers’ historical fantasy, Britannia. His stint as the brutally authoritarian Governor in three seasons of The Walking Dead from 2012-2015 ensured that Morrissey was exposed to a massive international audience, and his already enviable level of employability soared accordingly.

But it’s on TV that Morrissey has left his most indelible mark, and he has starred in several of the most acclaimed dramas in recent memory. He starred in Danny Brocklehurst’s BBC One drama The Driver, played MP Stephen Collins in Paul Abbott’s political thriller State of Play, and turned himself into Gordon Brown opposite Michael Sheen’s Tony Blair in The Deal, written by Peter Morgan and directed by Stephen Frears (the latter piece bagged lifelong Labour supporter Morrissey a Best Actor award from the Royal Television Society). Other major credits included Red Riding, South Riding, The Missing, Thorne, and the role of unsmiling Roman general Aulus Plautius in the Butterworth brothers’ historical fantasy, Britannia. His stint as the brutally authoritarian Governor in three seasons of The Walking Dead from 2012-2015 ensured that Morrissey was exposed to a massive international audience, and his already enviable level of employability soared accordingly.

Now he’s back in the second series of James Graham’s Sherwood (BBC One), the writer’s punishing examination of the lingering aftermath of the 1984 miners’ strike in a close-knit Nottinghamshire community. Simultaneously, Morrissey can be found in Danielle Ward’s earthy and abrasive comedy Daddy Issues (BBC Three), where he plays Malcolm, the pitifully inept father of single-mum-to-be Gemma (Aimee Lou Wood). “It’s like London buses, isn’t it?” Morrissey deadpans. “You wait for a Morrissey for ages and then three come along all at once.”

ADAM SWEETING: You’re renowned for doing a lot of deep research into your roles. Did you do a lot for Ian St Clair, for Sherwood?

DAVID MORRISSEY: Yeah, well, of course, it was on top of what I'd done originally [in Series 1] because I'm returning to the character. In the initial series, I would do things like create a backstory for him and find out how he got on the ladder in the police force and stuff. But in season two, he's got a new job. He runs a thing called the Violence Reduction Unit. They do exist, there's one in Middlesbrough. There's one in Nottingham as well. Because James Graham had put Ian into this new role, I went to find that new role. And I spoke to people in those professions, and they were quite amazing people. The guy in Middlesbrough I spoke to was ex-military, he'd been in Afghanistan and stuff. And the guy who I met in Nottingham, who set up the unit, was an ex-copper, so he was a bit like my character (pictured below, Morrissey and Leslie Manville on the Sherwood set). And then so I was able to talk to him about the problems in terms of gaining trust in a community when you've been a police officer. And, you know, that thing of him having to work hard with community leaders and people on the streets to make sure that they knew he wasn't a grass, that they could trust him. These guys sort of bring joined up thinking around things like housing, public health, police, hospitals, prison officers.

And then so I was able to talk to him about the problems in terms of gaining trust in a community when you've been a police officer. And, you know, that thing of him having to work hard with community leaders and people on the streets to make sure that they knew he wasn't a grass, that they could trust him. These guys sort of bring joined up thinking around things like housing, public health, police, hospitals, prison officers.

There’s almost a sort of Wild West vibe in the show. You've got these rival dynasties going hammer and tongs, you almost expect Kevin Costner to come riding in. It's a gripping story, but the violence is quite shocking.

Yeah. And, you know, there's evidence for that violence. James has put it into a drama, but I think all the violent events you see in Sherwood 2, I think you wouldn't have to look too hard to see parallel things that have happened that he has drawn on, really. It’s interesting, the term “Wild West”, and the reference to Costner, because it gives it a sort of romanticism. It gives it this sort of fictionalized, big screen, big valley sort of colour to it. And it's not that at all. No. Even though we're dealing with a drama here, I think James is someone whose dramas are very much about Britain right here, right now. Not just in the UK but across the world we're in a volatile time, a time where there's a lot of anger and a lot of misinformation.

People want to have some sort of rock solid certainty that they can live by. And what we know, I think, is that that type of certainty message comes from the extremes. The sort of binary messages – it's them, not you – those types of very simple messages come from the far right and the far left. And what people grab hold of in times of uncertainty, particularly economic uncertainty, are headlines, and nobody lives there. And I think that's where James is working, in that area of uncertainty. And also the lack of condemnation inside his writing – he doesn't seem to take sides. He's obviously a man of the left. We've heard recently of him talking about working class voices in television and stuff like that. But he's also a person who will look at someone like Robert Lindsay's character [an unscrupulous business entrepreneur] in the show, too (pictured below, Morrissey with John Simm in State of Play).

Like the people who decided to not join the National Union of Mineworkers during the miners' strike. He will look at those people. And he will have understanding and empathy for them and try to see their side of their argument. And that's really important because there isn't going to be a man on a white horse riding into town. You know, there isn't a Clint Eastwood figure. There isn't a Kevin Costner figure. It's not a romanticised vision of the world. It's a very stark and I think a very human look at where we are now in this country. And I think that's what's brilliant about it.

Like the people who decided to not join the National Union of Mineworkers during the miners' strike. He will look at those people. And he will have understanding and empathy for them and try to see their side of their argument. And that's really important because there isn't going to be a man on a white horse riding into town. You know, there isn't a Clint Eastwood figure. There isn't a Kevin Costner figure. It's not a romanticised vision of the world. It's a very stark and I think a very human look at where we are now in this country. And I think that's what's brilliant about it.

Do you get to discuss the scripts with him?

Yeah, yeah. All the time. Not just me. I mean, you know, he's very available, James. Before Sherwood 1, I didn't know anything about it, but I adored his work. And he just said, do you want to meet up? And we went for a walk in London and he just started to talk, ruminate about what he was thinking of doing. I was going to say he's open to collaboration. I don't think that's right. I think what he's open to is discussion. And he listens and he hears you. And then he goes away and he writes it and he brings it back. He's available and not all writers are. Some people just give you the script and that's it and you do it. I don’t respond to that well. But I think I'm lucky in that I do tend to be involved at the early stages of it rather than, you know, can you start on Monday?

Let’s talk about Daddy Issues. Do you have to have a separate sort of comedy head that you put on, or does it not work like that?

No, I think that's a good way of putting it. I think it's not so much a comedy head, but it's sort of an investment in the world. There's a different world that has different rules. Malcolm [ Morrissey’s character] is a man who's never seen a spreadsheet in his life. I mean, he's just all over the place. He's sort of an innocent. It's like he's discovering the world as it's coming at him, like he's never seen it before. And that creates comedy because he's a child in a man's body and he's having to be parented by his daughter, Gemma (pictured below, Morrissey with Aimee Lou Wood as Gemma). And I just love his gauche innocence, really. I love the fact that he's so sort of raw and full of emotion. But the other thing about Malcolm is I don't think he's got a bad malicious bone in his body. He's a bit angry at his ex-wife, but he would crumble if he saw her. He's not a violent man or angry or bitter. He's just sort of lost. And I quite like that. And he's vulnerable in the sense that he can be manipulated by the people around him. There's a sadness in that, but there's also a lot of comedy in it. So how has he lived so long and learned so little?

So how has he lived so long and learned so little?

Well, I don't know about you, but I've got a lot of mates who I've asked that question of as well in my life. For all Malcolm’s downtroddenness, he still occupies a privileged place because he's a white heterosexual male. And the world is geared for that, whether you're aware of that or not. So he can go through life with those advantages and they sort of play out for him. He also works. He gets a job and I think as long as he's got no responsibility he's fine, you know, it's stacking shelves and he can do that. I think how he survived is with the bare minimum. I mean, I think he's a musician. I think he's a drummer.

No drummer jokes...

I love that joke about the drummer who wants to be a guitarist. So he goes into this shop and says to the guy, can I have a full set of guitar strings? I've got guitars, got no strings. And the guy says to him, you're a drummer, aren't you? He says, yes I am. How do you know that? He says, because this is a fish and chip shop. And I think Malcolm's got a bit of that about him. He survives on the bare minimum. And actually, when we meet him, he is barely surviving.

The squalor of his existence is spelled out quite graphically, isn't it?

Gemma gets there just in time. And we meet him at his most broken point, I would say, when he has absolutely got nothing and is full of self-pity and sort of incapable of looking after himself at all. But I think, in the past, as far as him being in a couple is concerned, I think his wife would say to him, I need you to do this. And he'd do it because he doesn't have an opinion and he's not going to take you on. And he'll accept all your anger and all your frustration. He's not going to fight back. He's not going to stand up for himself.

A kind of emotional punchbag.

Yeah. There's a scene where he goes to his sister's house, and his sister is married to a loud-mouth bully. And I always felt that that type of person was their father. They grew up in a house where they were bullied, where they were shouted out, where every ounce of character and idiosyncratic personality was kicked out of them. They're two frightened people. And like everyone does, you repeat those patterns in your adult life.

I was reading an interview where you were saying that you felt you weren't well enough educated, that your schooling let you down.

I was reading an interview where you were saying that you felt you weren't well enough educated, that your schooling let you down.

Yeah, I've always been very angry that my education, my secondary education was decided by an 11 plus exam. And I failed that exam. And to be examining children at that age to determine what happens to them for the next five years, I thought was pretty shoddy. And I've always had a bit of a thing about it. And when I discovered my drama group, which was at the Everyman Theatre in Liverpool, that saved my life. What it did was it encouraged my curiosity and my inquisitiveness. My educational establishment was doing the exact opposite. It was quashing my curiosity and my inquisitiveness. It was asking me to fit into a type of education which was basically a memory test. And it wasn't about fulfilling my desire to become a fully rounded human being. And drama did do that.

You had quite an amazing group of contemporaries, didn't you? Like the McGann brothers and Cathy Tyson and Ian Hart.

All of whom I’m still mates with. I've seen Cathy a lot. Ian's my best mate. And Paul McGann I know really well. I was out with Paul not so long ago. So, yeah, it was good. But then, you're not in a place like that just to become an actor. You're there to experience life and have a voice and sort of find your empathetic gene, I would say. Just have fun, you know.

Which directors would you cite as ones that have had the most impact on your career?

Oh, so many, you know, I worked with Paul Greengrass years ago, who I think is quite amazing. Lewis Arnold, who I did The Long Shadow with recently. Adrian Shergold in the old days, I did a thing with him called Holding On, written by Tony Marchant, and he was a great director, television director. In the theatre, I would say Deborah Warner. I worked with her in the early days and really loved working with her. David Yates I worked with, who went on and did all the Harry Potter stuff. He did State of Play, I really thought he was a great director.

Stephen Frears?

Stephen Frears?

I adore Stephen Frears! Stephen was somebody who I really, really admired for years, and I got to work with him and he didn't disappoint. What I love about him is he doesn't play any games, so you know very quickly where you are with him. He doesn't overly praise you, but if he's not saying anything to you, you're doing all right, you know. I don't find him scary or anything. He's just someone who's very clear and I guess you would describe him as old school in the sense that he's the boss, you know. I interviewed him once at BAFTA and it was difficult because he doesn't like talking about himself. It's not what he's good at and he didn't really want to be there, but then I spoke to him about Dangerous Liaisons and I could see his eyes filling with tears at the memories of working with John [Malkovich] and he's a very emotional being. Like all great directors or artists, he's really curious and interested in the human condition (pictured above, Morrissey as Gordon Brown in The Deal).

He has a pretty amazing track record of work.

Yeah, his body of work is very different. He's somebody who's taken the baton from those directors like Tony Richardson, Carol Reed, Lindsay Anderson, that has been passed on to people like him and Ken Loach. They're the people who we see have come through those ranks and interestingly enough, through television. You know, that Play for Today format, things like Cathy Come Home. And Stephen did My Beautiful Laundrette, and that came through a television company because it was Film 4.

Do you think the internationalisation of TV and film through the big streaming companies means we're losing that kind of British sense of filmmaking or programme making?

Well, we're here to talk about Daddy Issues and Sherwood, so I would say that that sort of flies in the face of that. But yeah, I see that. I mean, when you think of things like, whatever you think of it, Downton Abbey, it’s very British. It's chocolate box British, but it's British. It might be a Britain designed for the American market, but it's definitely Britain. You see something like Happy Valley… we could do more, but I think ITV, BBC, Channel 4, Sky even, are British producers of drama that really look at the people that are going to turn on their television screens in this country.

They have to be international as well sometimes, it is a business, but they look at what's going on around them. Something like Sherwood, what I've always felt is, the more specific you can be about where you are, the story you're telling, the people that you're telling about, the more international you are. Because the basics of the human condition are the same everywhere.

What did you learn from being in The Walking Dead? (pictured left)

What did you learn from being in The Walking Dead? (pictured left)

I loved it. What you're doing in Walking Dead, shows like that, you’re creating a universe. It's world-building writing, and if you're true to the world that you've created, then it will always be a success. And the producers of that show… Robert Kirkman, he did the graphic novels and is a writer and producer. Gale Ann Hurd, who’s a producer and she did Terminator and Alien. And Greg Nicotero, who's also one of the producers and directors, and also the man who controls all the makeup, he does all the prosthetics and stuff. He's a genius. They know the world and they honour the world all the time. It's a really well run show, but it's like a military machine. Every hour is eight days, so every episode takes eight days to shoot. And in order to get it in on time, on budget, there needs to be a lot of elements working together all the time.

After Walking Dead, did you find that you were getting a different kind of appreciation or interest from audiences or directors or TV companies?

Yeah, 100 per cent. It was the biggest show in the world for a while. It would be Game of Thrones and it would be us. And if you look at the numbers, and I'm one of the major characters in a show that's the number one show in the world, then yeah, that sort of does translate into people saying, “oh, should we get him in the office?” But then you might get offered a lot of zombie genre-like shows, and it's up to you what you choose from those offers that still challenges you and changes you. Because whenever I've played a strong character in a drama that's done well, you can bet your life that in the weeks after it's been on the telly, the next four or five scripts that come in will be, do you fancy playing this politician? Do you fancy playing this zombie madman guy who kills lots of people? You've got to hold your nerve and think what interests me? Do I want to tread that path again or not?

It must be difficult to make that choice. You might be thinking have I made a mistake?

Well, yeah, of course, but they're the problems of success. So then you're in a position where you go, “this is what success looks like. I'm having trouble choosing.” The worst thing is going, “I've got nothing to choose from.” So you always want to be with the good problems. You don't want to be in the other place. I would never go “oh, it's so difficult having all these choices.” Obviously if you’re the manager of Chelsea, probably it's a different thing. But it's all good. That's where I want to be. And the important thing is, when you make the choice, make the choice. Don't do that thing of sitting there going, “oh, if only I'd done that.” Be where you are in the job you're doing and love it.

I was reading the interview with you in The Times, and the bloke was asking you about posh actors.

Yeah. It's interesting, isn't it? Because the way these things can be framed is when you champion one thing, like working class voices in the entertainment industry, it can be translated as that you're trying to shut down the voices of somebody else. And I'm not against them [posh actors] at all. They're all there with fucking brilliant talent. I’m just saying look, this is a big playing field here. And my big bugbear about all this is education. When you have someone like Michael Gove saying that in a state educated system, he's going to downgrade soft options, and soft options are the arts. Soft options in state schools, as far as the Tory government was concerned, were art, drama, media, music. So you're immediately saying to state educated children, these are not worth as much as the other stuff and so they're not for you (pictured below, Morrissey with Nicolas Cage in Captain Corelli's Mandolin). While at the same time in the public school system, they have theatres and orchestras that would rival the West End and the Royal Philharmonic Society. So right there, right now, you're creating this massive divide. You're saying for certain educated people, certain educated establishments, look at this. Isn't this wonderful? Why don't you explore this type of life, this type and everything that it brings? It might be your profession. And you're saying to a whole other group of people, don't go there because it's not worth it. Don't explore that part of yourself.

While at the same time in the public school system, they have theatres and orchestras that would rival the West End and the Royal Philharmonic Society. So right there, right now, you're creating this massive divide. You're saying for certain educated people, certain educated establishments, look at this. Isn't this wonderful? Why don't you explore this type of life, this type and everything that it brings? It might be your profession. And you're saying to a whole other group of people, don't go there because it's not worth it. Don't explore that part of yourself.

If anything, you’d think state schools should have more arts and drama.

Well, exactly. And you can have them without them quashing maths and English and science. If you look at something brought in by John Major, actually, with the lottery system, he said, “OK, let's use lottery money to look at sport.” And if you look at the Olympics, so many working class people who are good at sport were given the backing and were given the encouragement and the financial clout to pursue what they were good at. And that translates into the Paris Olympics and us coming fourth in the medal table or whatever.

Do you feel that the stage is the most kind of primal place where you perform, where you’re closest to some kind of expression?

I think the real difference is you can unpack something and put it back together, that you are given time in a rehearsal space to really explore the piece in all its building blocks. You quite rarely have that on television. Most often, the company comes together quite late, not just because of casting or whatever, it's to do with actors having their deals done and stuff like that. So you have less time to unpack and put it back together. In theatre, that's what it's all about. It's about getting there on the first day, and then you've got four to six weeks, maybe a bit longer in some cases, where you can you can start to explore, you can go down blind alleys, you can fall over on your arse and everybody's there to support you. And then with your performance there's a live audience, and that’s the next element of what you're doing.

I did a Martin McDonagh play called Hangmen a couple of years ago, and I did Julius Caesar at the Bridge with Nick Hytner, where I played Mark Antony, not so long ago. And they're experiences that you really cherish, because there's just something about being in that space and performing in that way… you know, the referee blows the whistle and you're on the pitch, and it's really now and it's in your hands. What happens when you're filming is in that moment, it's in your hands when the camera's rolling, but you hand that over to someone else and they go and do what they want with it, you know, cut it or put it somewhere else in the story or whatever. I do think theatre has an immediacy, but with all of them, film, television, radio, theatre, it's always about the script. My initial aim is “do I want to do this? Do I like it? Is it challenging?” You know, that's my thing (pictured below, Morrissey in The Ones Below, 2015).

Pick three of your favourite actors of all time, who you admire or you learned from.

Pick three of your favourite actors of all time, who you admire or you learned from.

One of the first actors I was aware of was Michael Bryant, who was in an episode of Colditz that I loved. But when I was at the Everyman Theatre, I met actors, I saw them in the bar and stuff. And there were people like Anton Lesser, George Costigan, and they were real people to me. They sort of demystified it, they weren't Robert De Niro or whatever. They were really good actors, I would say in the case of Anton, quite brilliant actors. And they were walking down the road, you know, in my theatre. Jim Broadbent was at the Everyman when I was a kid and he was just extraordinary. When I first came to London, I went to the theatre and saw Glenda Jackson. She just blew me away. I thought, how did you do that? James Hazeldine was an actor I worked with in my first job. He's sadly no longer with us. He was an actor I totally admired.

And then, the actors who I looked at from afar, they would be people like Ian Holm. I thought there's something about how he inhabits a role in such a subtle way. I loved him. And then, some of them I got a chance to work with. John Hurt was an actor who I just thought was absolutely extraordinary. It was like he had layers of skin taken off him and he was just open to the elements. And I worked with him twice, and he became a great friend. I worked with Pete Postlethwaite, and he was just someone you could shoot the breeze with. And they'd shout action and he was like this magician that just suddenly transformed, shape-shifted right in front of you. When I was at the Everyman I would have been about 14. I went up to all the actors and said I want to be an actor. None of them told me to fuck off. They all gave me their time and were generous. And as I've grown up I’ve met some of them again and been able to thank them.

One little thing about Sherwood. There’s a moment when you ask Leslie Manville to come and have a drink with you, and the look on her face is amazing.

It’s just awesome. But I just think Leslie is phenomenal, and you always knew she was brilliant. But also Monica Dolan, Lorraine Ashbourne, Phil Jackson. And Robert Lindsay. And also Stephen Dillane, who I've just been in awe of for years and years. When you're in a James Graham piece, you tend to get a great cast. Working with all of them was just such a joy, really.

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Add comment