“Two-percent movie-making and 98% hustling,” Orson Welles sighed not long before his death in 1985. “It’s no way to spend a life.” His 1962 film of Franz Kafka’s The Trial was his penultimate full-scale completed feature, only 1965’s Chimes at Midnight similarly allowing him a regular director’s resources during his last quarter-century (the fraudulent documentary F for Fake from 1973 was later conjured from scraps with filmic legerdemain).

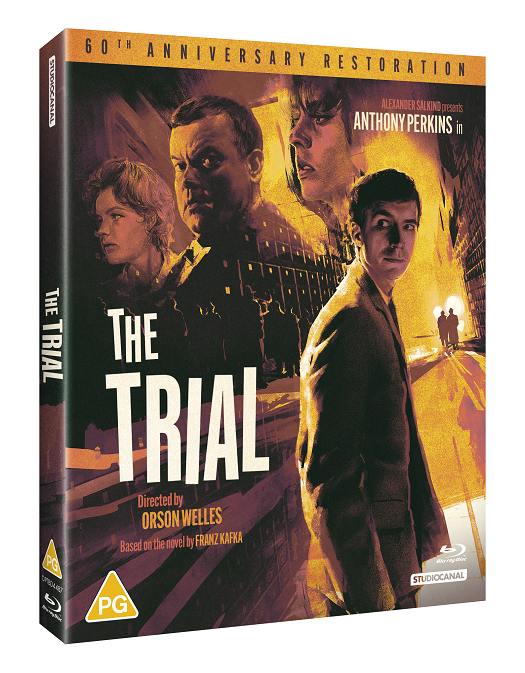

Kafka’s paranoid tale, written as World War One began, and predictive of the totalitarian mindset which would murder his own family in the Holocaust, sees Josef K traduced and harried for unnamed and so inescapable crimes, lost in inhuman bureaucracy and finally slaughtered, he gasps with his last breath, “like a dog”. Welles shot in Cold War Yugoslavia and Paris’s abandoned Gare d’Orsay station and hotel, mixing communist brutalism and cavernous baroque. The cast similarly reflected its international backing, with Anthony Perkins’ K joined by Jeanne Moreau, Romy Schneider, Akim Tamiroff and Welles himself. The Trial therefore feels unmoored, as accents and acting styles jostle through a series of great, distinct scenes.

K awakes into a nightmare, finding a man who seems to be a policeman in his room. The ceiling presses down on him (Welles left 20 centimetres above Perkins’ head, with his cameraman Edmond Richard crouched beneath him), as accusations are laid, and guilt presumed. “You must have done something,” Jeanne Moreau’s showgirl tells him, till even his own presumption of innocence evaporates, revealing a mess of hopeless, human flaws.

K awakes into a nightmare, finding a man who seems to be a policeman in his room. The ceiling presses down on him (Welles left 20 centimetres above Perkins’ head, with his cameraman Edmond Richard crouched beneath him), as accusations are laid, and guilt presumed. “You must have done something,” Jeanne Moreau’s showgirl tells him, till even his own presumption of innocence evaporates, revealing a mess of hopeless, human flaws.

Welles makes K an American liberal, talking ineffectually of civil rights. “A victim of society?” Welles’ Advocate asks ironically. “I’m a member of society,” K insists. Perkins shows traces of the boyish, almost goofily innocent qualities Hitchcock subverted in Psycho, sometimes slipping into hysterically dark screwball comedy, like Jimmy Stewart trapped in a police state. In a deleted scene on this disc, he dances and skips alone across office desks after hours, as if in a musical. His body often seems elongated, part of the film’s dream-like distortions. He’s especially awkward with women, from earthy Moreau to Schneider’s feline, erotic nurse (pictured below centre with Perkins and Tamiroff), unable to respond to their advances. Welles later reportedly said he had played on Perkins’ closeted gayness, which is how it looks now. His voice twitchily tries for calm while drowning in society’s demands. Welles filmed with an awareness of the Holocaust, referenced in a tableau of half-naked, numbered European grotesques awaiting judgement, and the Bomb, chucked in at the end. An infinitude of identical desks and clacking typewriters at K’s workplace connects mid-20th century American impersonality to the secret police state he finds operating behind nearby doors, as if backstage.

Welles filmed with an awareness of the Holocaust, referenced in a tableau of half-naked, numbered European grotesques awaiting judgement, and the Bomb, chucked in at the end. An infinitude of identical desks and clacking typewriters at K’s workplace connects mid-20th century American impersonality to the secret police state he finds operating behind nearby doors, as if backstage.

The proto-noir shadow-play Welles and cinematographer Gregg Toland created for Citizen Kane, and which he had revisited with malignant murkiness in his most recent film, Touch of Evil (1958), finds wild expression here as Welles riffs on the possibilities of black-and-white cinema, which he remained devoted to. In a torture scene in a closet, a bulb’s light-source swings with the rough violence of the belt slicing at a man’s stripped chest, glints of humour making the savagery worse. Welles later indulges in extreme Expressionism, Perkins’ shadow roughly capering behind him like a doppelganger with a life of its own as he’s chased through Third Man-style tunnels.

Welles’ Advocate (pictured below with Perkins) personifies why all these brilliant flashes don’t add up in conventional ways. He is a typical Welles grotesque, his apartment created in some especially Gothic, candlelit corner of the Gare d’Orsay. Talking through a smoking steam-towel ministered by Schneider’s sly nurse, or beneath a blanket, his big scene sees him modulate from a murmur to a roar, and sounds improvised (“He had trouble memorising his lines," Richard attests in one of the extras here, "It bored him”). Welles’ wryly monstrous presence unbalances Kafka's tale. Exiled by Hollywood, and subsisting in a Europe that wasn’t wholly his, Welles turned The Trial into a hybrid film, mixing fragments of his technocratic homeland, real Yugoslav grimness and modish concerns with the novel’s absurd Czech German Jewish darkness, its textural prefiguring of Caligari, Nosferatu and Mabuse. Welles relishes Kafka’s humour, but only fitfully finds the terror which still stalked the Cold War continent. It’s a rare late exercise of his exhilarating technique, on a film he can’t quite piece together.

Exiled by Hollywood, and subsisting in a Europe that wasn’t wholly his, Welles turned The Trial into a hybrid film, mixing fragments of his technocratic homeland, real Yugoslav grimness and modish concerns with the novel’s absurd Czech German Jewish darkness, its textural prefiguring of Caligari, Nosferatu and Mabuse. Welles relishes Kafka’s humour, but only fitfully finds the terror which still stalked the Cold War continent. It’s a rare late exercise of his exhilarating technique, on a film he can’t quite piece together.

The 4K restoration brings out Richard’s deep blacks and whites (designed to withstand the print’s expected delay and deterioration in Yugoslav customs). Previously released extras include Richard’s revealing reminiscences, Steven Berkoff on Kafka and Welles, and Julia and Clara Kupferberg’s middling TCM doc This Is Orson Welles, which leans on an interview with Welles’ daughter, Chris Welles Feder.

Add comment