Mank review – David Fincher’s brilliant, bitter-sweet paean to Hollywood’s Golden Age | reviews, news & interviews

Mank review – David Fincher’s brilliant, bitter-sweet paean to Hollywood’s Golden Age

Mank review – David Fincher’s brilliant, bitter-sweet paean to Hollywood’s Golden Age

Gary Oldman is on top form as Citizen Kane’s scathing screenwriter, Herman Mankiewicz

For so much of the year, Tenet was cited as the film that was going to save cinema – the tentpole extravaganza that would draw virus-conscious punters back to the big screen. The assertion was always fanciful, the pandemic being too long a haul; with no disrespect to Christopher Nolan, the fanfare around his latest spoke more of industry desperation than reality.

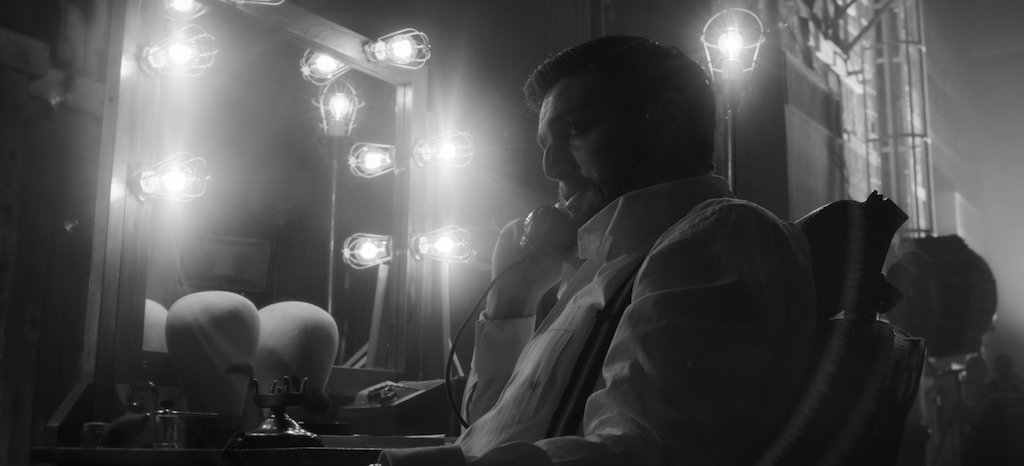

Meanwhile, along comes Mank, David Fincher’s account of the controversial genesis of Orson Welles’ landmark Citizen Kane, oft-cited as the greatest film ever made. It stars Gary Oldman as Herman Mankiewicz, the sozzled, sardonic scribe who, depending who’s talking, was wholly or at least primarily responsible for the Kane script – despite Welles’s attempt to take sole credit – and is the focal point of Fincher’s rambunctious, bitter-sweet, brilliant paean to Hollywood’s Golden Age.

And here’s the thing. Mank may have been made for Netflix, the screening giant many fear as the enemy of cinema; it may play best to cinephiles who can drink in the references and the ravishing, retro shooting style; it’s a talky throwback of a film, commercially out of step with the times. And yet this really feels like the movie we all need right now – not the saviour of cinema, but an intelligent, gorgeous reminder of what cinema, truly great cinema is all about.  Fincher’s first film since 2014’s Gone Girl is a labour of love, written by his late father Jack Fincher many years ago, waiting for the right moment. It’s a film about filmmaking in the micro, macro and meta: it deals both with one man’s creative process and an industry which eats creatives for breakfast; it’s about the genesis of a particular film, Kane, using many of the tropes and techniques that film marshalled in such a seminal way; it’s a snapshot of a Hollywood era in thrall to money, moguls and the media, which throws a spotlight on the here and now; it pays homage to Kane, while making its central character someone other than the man most closely associated with it.

Fincher’s first film since 2014’s Gone Girl is a labour of love, written by his late father Jack Fincher many years ago, waiting for the right moment. It’s a film about filmmaking in the micro, macro and meta: it deals both with one man’s creative process and an industry which eats creatives for breakfast; it’s about the genesis of a particular film, Kane, using many of the tropes and techniques that film marshalled in such a seminal way; it’s a snapshot of a Hollywood era in thrall to money, moguls and the media, which throws a spotlight on the here and now; it pays homage to Kane, while making its central character someone other than the man most closely associated with it.

And amid and around all of this, it’s a damn good yarn – funny, whipsmart, evocative, wonderfully acted and teeming with inventiveness.

It’s 1940. Orson Welles (Tom Burke) is the 24-year-old “boy wonder” of the New York stage, who has been lured to Hollywood by struggling studio RKO and unprecedented creative autonomy. Welles charges Mankiewicz to provide him with a script, arranging for the alcoholic writer with a newly broken leg to be deposited in a Californian desert ranch – and “dry house” – with a secretary (Lily Collins, pictured above with Oldman), a nurse and producer John Houseman breathing down his neck. He’s got 60 days.  Once top of the pile of studio writers, at this point the self-destructive Mankiewicz is all washed up. But he has his story, which will involve “hunting dangerous game”, namely yellow press baron William Randolph Hearst (Charles Dance, above right), with Hearst’s actress lover Marion Davies (Amanda Seyfried) as collateral damage. To write his headline-grabbing tale of wealth and power, hubris and lost idealism, he’s going to have to betray friendships, risk ruin and rediscover his mojo.

Once top of the pile of studio writers, at this point the self-destructive Mankiewicz is all washed up. But he has his story, which will involve “hunting dangerous game”, namely yellow press baron William Randolph Hearst (Charles Dance, above right), with Hearst’s actress lover Marion Davies (Amanda Seyfried) as collateral damage. To write his headline-grabbing tale of wealth and power, hubris and lost idealism, he’s going to have to betray friendships, risk ruin and rediscover his mojo.

Like Kane, Fincher’s film darts about in time – between 1940 and the desert, as Mank dictates from bed and plays host to a succession of friends trying to talk him out of it; and the early Thirties, when the writer becomes irretrievably disillusioned with the corrupt Hollywood machine and his own part in it. One passage leads towards the inevitable confrontation with Welles over credit, the other his political feud with studio boss Louis B Mayer (Arliss Howard, below centre) and Hearst.

Unlike Kane, which adopts multiple perspectives in its investigation of the real person behind the mythic protagonist, this is all Mankiewicz – Mank to his friends. And Oldman is in every scene, skilfully delineating a fascinating, complicated, extremely appealing mess of a man.

It’s odd how much dreck the Englishman has accepted in his time, and so all the more satisfying to see how easily he responds to the great parts – from the last decade: Smiley, Churchill, Mankiewicz. Here he manages something that’s so difficult: to be larger than life – a scurrilous wit, everyone’s favourite drunken provocateur – while seldom really grandstanding, and often simply observing, listening or gently probing; hell, for half of the film he’s immobile – passed out drunk, or stuck in bed with his leg in plaster – and still you can’t take your eyes off him.  The key to Mank’s character lies in his brother and fellow writer Joe’s assertion that he has become the “court jester” of the Hollywood court; Oldman nudges that notion in the direction of the Shakespearean fool – whose tragic master, and as much blueprint for Charles Foster Kane as Hearst, is Welles himself.

The key to Mank’s character lies in his brother and fellow writer Joe’s assertion that he has become the “court jester” of the Hollywood court; Oldman nudges that notion in the direction of the Shakespearean fool – whose tragic master, and as much blueprint for Charles Foster Kane as Hearst, is Welles himself.

Oldman has always given good drunk, but what’s most notable here is the bantering warmth of the performance, notably alongside his female co-stars: Seyfried, Tuppence Middleton as Mank’s long-suffering, yet equally dry-witted wife Sarah, Lili Collins as the prim English secretary Mrs Alexander, and Monika Gossmann as the nurse Fräulein Frida. One joyous shot of Oldman and Collins has all the prairie romanticism of a John Ford western.

Around Mank, Fincher has built a mouth-watering gallery of characters. Seyfried (pictured left) is terrifically engaging as Davies, lending humour and sassy depth to the woman who, despite her friendship with the writer, would be cruelly misrepresented in Kane. Howard makes a great cartoon villain of MGM chief Meyer, his mind always on the dollar rather than the frame, sucking up to the wealthy Hearst whose bankrolling of Davies’ films enables Meyer to pay even less for his product. At times, it’s tempting to see Meyer as the Giuliani to Hearst’s Trump, a sycophantic enabler to a power-hungry tyrant. And yet Dance is always going to be classier than a Donald; he gives Hearst a suitably vampiric air, a sinister, almost seductive graciousness.

Around Mank, Fincher has built a mouth-watering gallery of characters. Seyfried (pictured left) is terrifically engaging as Davies, lending humour and sassy depth to the woman who, despite her friendship with the writer, would be cruelly misrepresented in Kane. Howard makes a great cartoon villain of MGM chief Meyer, his mind always on the dollar rather than the frame, sucking up to the wealthy Hearst whose bankrolling of Davies’ films enables Meyer to pay even less for his product. At times, it’s tempting to see Meyer as the Giuliani to Hearst’s Trump, a sycophantic enabler to a power-hungry tyrant. And yet Dance is always going to be classier than a Donald; he gives Hearst a suitably vampiric air, a sinister, almost seductive graciousness.

And through just a handful of brief appearances, Tom Burke (pictured right) captures perfectly Welles’s voice and gait, his showmanship and egotism (if not his youth). “I’m toiling with you in spirit Mank,” he purrs down the phone, while actual spirits are all that Markiewicz needs to get the job done. When the two clash, Welles’s furniture-throwing tantrum gives Mank a new idea. “An act of purging violence…..” he scribbles, positing one of Kane’s most memorable scenes. Burke leaves a deliciously-timed pause, before mumbling “maybe” and careering out of the room.

And through just a handful of brief appearances, Tom Burke (pictured right) captures perfectly Welles’s voice and gait, his showmanship and egotism (if not his youth). “I’m toiling with you in spirit Mank,” he purrs down the phone, while actual spirits are all that Markiewicz needs to get the job done. When the two clash, Welles’s furniture-throwing tantrum gives Mank a new idea. “An act of purging violence…..” he scribbles, positing one of Kane’s most memorable scenes. Burke leaves a deliciously-timed pause, before mumbling “maybe” and careering out of the room.

While Fincher snr’s zestful script has the swift, overlapping dialogue of the period (already well-established by screwball comedies before Kane), his son employs the techniques enhanced and made famous by Welles and cinematographer Gregg Toland, notably deep focus, high contrast, low angle black and white camerawork, the pronounced fade outs, the theatrical lighting and willingness to shoot people in shadow, all of which evoke the period and remind us of the mouth-watering wonders that cinema could create before CGI ever came along.

Now and again there’s a frisson of familiarity: a close-up of Mank dropping a liquor bottle mirroring the snow globe’s tumbling from Kane’s fingers, or shafts of light that recall the banker’s inner sanctum. For the most part, though, Fincher is reemploying the tools to reveal how fresh and exciting they remain. Interestingly, this film’s relationship with those bedrock tools of the trade has the same exhilarating effect as Alfonso Cuarón’s Roma – another film bankrolled by Netflix.

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Film

London Film Festival - from paranoia in Brazil and Iran, to light relief in New York and Tuscany

'Jay Kelly' disappoints, 'It Was Just an Accident' doesn't

London Film Festival - from paranoia in Brazil and Iran, to light relief in New York and Tuscany

'Jay Kelly' disappoints, 'It Was Just an Accident' doesn't

Iron Ladies review - working-class heroines of the Miners' Strike

Documentary salutes the staunch women who fought Thatcher's pit closures

Iron Ladies review - working-class heroines of the Miners' Strike

Documentary salutes the staunch women who fought Thatcher's pit closures

Blu-ray: The Man in the White Suit

Ealing Studios' prescient black comedy, as sharp as ever

Blu-ray: The Man in the White Suit

Ealing Studios' prescient black comedy, as sharp as ever

The Woman in Cabin 10 review - Scandi noir meets Agatha Christie on a superyacht

Reason goes overboard on a seagoing mystery thriller

The Woman in Cabin 10 review - Scandi noir meets Agatha Christie on a superyacht

Reason goes overboard on a seagoing mystery thriller

London Film Festival 2025 - crime, punishment, pop stars and shrinks

Daniel Craig investigates, Jodie Foster speaks French and Colin Farrell has a gambling habit

London Film Festival 2025 - crime, punishment, pop stars and shrinks

Daniel Craig investigates, Jodie Foster speaks French and Colin Farrell has a gambling habit

I Swear review - taking stock of Tourette's

A sharp and moving tale of cuss-words and tics

I Swear review - taking stock of Tourette's

A sharp and moving tale of cuss-words and tics

A House of Dynamite review - the final countdown

Kathryn Bigelow's cautionary tale sets the nuclear clock ticking again

A House of Dynamite review - the final countdown

Kathryn Bigelow's cautionary tale sets the nuclear clock ticking again

theartsdesk Q&A: Idris Elba on playing a US President faced with a missile crisis in 'A House of Dynamite'

The star talks about Presidential decision-making when millions of lives are imperilled

theartsdesk Q&A: Idris Elba on playing a US President faced with a missile crisis in 'A House of Dynamite'

The star talks about Presidential decision-making when millions of lives are imperilled

Urchin review - superb homeless drama

Frank Dillane gives a star-making turn in Harris Dickinson’s impressive directorial debut

Urchin review - superb homeless drama

Frank Dillane gives a star-making turn in Harris Dickinson’s impressive directorial debut

Mr Blake at Your Service review - John Malkovich in unlikely role as an English butler

Weird comedy directed by novelist Gilles Legardinier

Mr Blake at Your Service review - John Malkovich in unlikely role as an English butler

Weird comedy directed by novelist Gilles Legardinier

Don't Let's Go to the Dogs Tonight review - vivid adaptation of a memoir about a Rhodesian childhood

Embeth Davidtz delivers an impressive directing debut and an exceptional child star

Don't Let's Go to the Dogs Tonight review - vivid adaptation of a memoir about a Rhodesian childhood

Embeth Davidtz delivers an impressive directing debut and an exceptional child star

Add comment