In Sight & Sound’s recent Greatest Films of All Time poll, Barbara Loden’s Wanda (1970) placed joint 48th with Ordet (1955), just ahead of The 400 Blows (1959) and The Piano (1992). Loden’s existential indie drama about an uneducated working-class Pennsylvanian woman (played by the writer-director herself) haplessly fleeing the role society allotted her might lack the intellectual heft of Chantal Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman, 23 Quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975), which topped the poll, but it’s the more accessible and compelling film.

Loden made a diffident, self-deprecating guest when she appeared on talk shows to promote Wanda, the only feature she wrote and directed. She had no plans to become a filmmaker, she said, but was urged to do so by her husband, Elia Kazan, who had a habit of taking some of the glory for Loden’s masterpiece after her death from cancer at the age of 48 in 1980.

I’d rather watch Wanda, as grim as it is, than any of Kazan’s films, with the possible exception of Wild River (1960). And if Kazan’s Splendor in the Grass (1961) is fascinating, it’s because Loden’s character – cruelly punished for her promiscuity – is everything Natalie Wood’s repressed protagonist can’t be.

Loden’s Wanda Goronski, first seen sleeping late on her sister’s couch in a house standing amid canyons of slag, arrives late for her divorce hearing, where her miner husband denounces her laziness and uselessness as a wife and as a mother to their two kids. Her willingness to relinquish custody and end the marriage isn’t motivated by a desire for freedom or self-actualisation; she simply recognises she doesn’t fit the mould of happy, hardworking homemaker.

Released from that prescription, Wanda drifts. That night she ends up in a motel bed with a guy who buys her a beer in a bar and jettisons her as soon as he can the next day.

Released from that prescription, Wanda drifts. That night she ends up in a motel bed with a guy who buys her a beer in a bar and jettisons her as soon as he can the next day.

After sleeping through the theft of her money in a cinema, Wanda returns to the bar and mistakes the man burgling it for the bartender. She tags along with the burglar, Norman Dennis (Michael Higgins), a morose, bullying career criminal. He feeds her, she sleeps with him, he slugs her – causing her to complain like a child. She unwittingly becomes his moll as he plans a much bigger robbery.

Shot on 16mm by cinematographer-editor Nicholas Proferes, intentionally flat and affectless, Wanda is a Warholian cinéma vérite dirge that might owe its veracity and power to the organic way it was shot on location in Pennsylvania and Connecticut for about $100,000 with a seven-person crew.

People encountered during production were invited into the cast, such as the retiree who memorably plays Norman’s infirm dad. Loden and Higgins, the only professional actors, improvised some scenes. Sounds and sights such as those of a buzzing radio-controlled model plane were grabbed on the fly.

Alienation, dislocation, and desperation animate most of the characters, including Wanda, who floats passively through the blighted urban terrain without volition, though she's fearful and has inklings of morality. She clings automatically to each of the two men she picks up; when she unquestioningly stuffs a pillow under her dress to mimic a pregnant woman as a disguise Norman has devised for her, she has no idea she is replicating the identity she's fled.

Though Wanda’s anti-heroine was criticized by 1970s feminists and critics like Pauline Kael for her dimness and lack of agency, her recognition that she has economic value as a sexual chattel and her submission to Norman disparages traditional gender roles. That said, her allure will likely enable her to survive.

Loden apparently had no knowledge of the women’s movement but was telling a version of her mid-1950s journey as a North Carolina native who had probably witnessed or experienced domestic violence as a child, and who’d worked as a pin-up model and chorus girl after moving to New York City at age 16.

That was before Ernie Kovacs hired her as a sidekick for his TV comedy show and her training at the Actors Studio brought her stage work – and in 1964 a Tony for creating Maggie, the Marilyn Monroe character, in Arthur Miller’s After the Fall, directed by Kazan. Perhaps only Loden and Kazan knew to what extent, if any, their turbulent marriage inspired Norman’s harsh coercion of Wanda and her soul-crushing complicity in their relationship.

Loden said she hated “slick pictures…. They're too perfect to be believable. I don't mean just in the look. I mean in the rhythm, in the cutting, the music – everything. The slicker the technique is, the slicker the content becomes, until everything turns into Formica, including the people.”

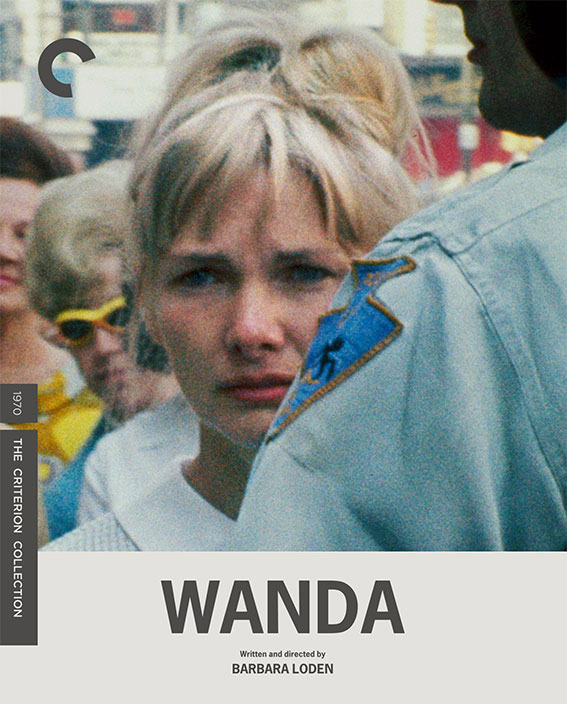

She was right. So, in a space of a few seconds, Wanda mops up spaghetti sauce from Norman’s plate when they eat together for the first time in a diner, takes a drag on her cigarette and quaffs her beer, and gets a piece of bread stuck on her lower lip, all the while quizzing her irritable companion about eating habits and why he’s swallowing pills. (Pictured left: Loden and Michael Higgins)

She was right. So, in a space of a few seconds, Wanda mops up spaghetti sauce from Norman’s plate when they eat together for the first time in a diner, takes a drag on her cigarette and quaffs her beer, and gets a piece of bread stuck on her lower lip, all the while quizzing her irritable companion about eating habits and why he’s swallowing pills. (Pictured left: Loden and Michael Higgins)

There’s a sensuous energy in her that wants to bloom, but she’s picked the wrong guy to have fun with. Up or down, provoking or demoralised, in motion or inert, Loden is a vital presence in a film that proved she was a natural director.

The Criterion Collection’s Blu-ray includes Loden’s stark half-hour educational film The Frontier Experience (1975), adapted by Joan Micklin Silver from diary entries by pioneer women and photographed by Proferes. Loden this time directed herself as a widow from Pennsylvania stranded with her kids on the unforgiving Kansas prairie in 1869. A kind of prequel to Wanda, albeit an optimistic one, it’s also an early contribution on film to the revisionist history of the West.

On the disc, too, is Katja Raganelli’s revealing hour-long documentary on Loden, filmed shortly before she died, and footage of Loden promoting Wanda on The Dick Cavett Show. (Loden’s appearance with fellow guests John Lennon and Yoko Ono on The Mike Douglas Show can be found on YouTube.) There’s also an audio recording, made in 1971, of Loden advising film students what they can expect when making their first films.

Criterion's website has invaluable material on Loden. Loden didn’t know it, but she was a visionary.

Add comment