There’s a rare combination of the sacred and the secular in Shubhashish Bhutiani’s debut feature Hotel Salvation (Mukti Bhawan). The young Indian director developed the film through a Venice festival production support programme awarded on the strength of his short film Kush, a prize-winner in 2013, and the combination of different worlds and talents that development process must have involved has worked very well indeed. There’s a rich and moving sense of atmosphere to Bhutiani’s tale of life and death – or, more exactly, the moment when life comes to an end, and a different dimension opens – as well as a father-son relationship that offers an incisive perspective on the values of contemporary India.

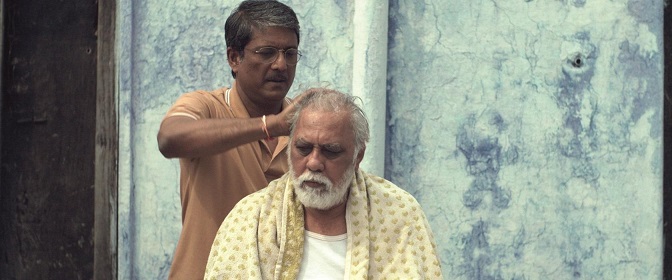

Representing an older, almost timeless world is Daya (Lalit Behl). At 77, he’s living his life out peacefully with his family, son Rajiv (Adil Hussain) and his wife and daughter. In contrast, the world of the younger generation is anchored in the stressed routines of the quotidian, particularly for Rajiv, a salaryman who seems always to be up against deadlines, as well as the pressures of an office swamped in paperwork. It makes for a degree of friction at home.

That certainly doesn’t mean the old man can’t be infuriating

But the drama really starts when, out of the blue, Daya announces to his family that he has had a dream that convinced him that his end is near, and that he wants to make a final pilgrimage to die in the holy city of Varanasi. Ahead of that, he ritually donates a calf at the temple, another natural, traditional episode in the wider rhythm of eternity.

Rajiv has permission from his boss to accompany his father to Varanasi, for a notional period at least, although he is still hassled over the phone all the time. They check in at the titular Hotel Salvation, and Bhutiani delights us with some of the other characters in residence. The establishment is run by the eccentric Mishraji, who believes that he knows when each of his residents will die: there’s a limit of 15 days for a stay, though it’s a restriction that in due course will be nicely waived.

The other guests may be waiting for the end, but that doesn’t stop them enjoying more everyday routines, among which is an unlikely evening television show titled Flying Saucer. Daya establishes a particular bond with Vimla (Navnindra Behl), a widow who had accompanied her late husband here years ago and has stayed on ever since. There’s much affectionate humour in their interaction: there’s a moment when Daya appears to be on his deathbed, surrounded by mourners and musicians, with Vimla trying to catch his last words. “What did he say?” a musician asks. “That you sing in tune, please,” she replies.

The other guests may be waiting for the end, but that doesn’t stop them enjoying more everyday routines, among which is an unlikely evening television show titled Flying Saucer. Daya establishes a particular bond with Vimla (Navnindra Behl), a widow who had accompanied her late husband here years ago and has stayed on ever since. There’s much affectionate humour in their interaction: there’s a moment when Daya appears to be on his deathbed, surrounded by mourners and musicians, with Vimla trying to catch his last words. “What did he say?” a musician asks. “That you sing in tune, please,” she replies.

As father and son explore their surroundings, including the sacred river and the ghats that lead down to its banks, they begin to understand one another better; Rajiv comes to reappraise the values of the world by which he has allowed himself to become so absorbed. That doesn’t mean the old man can’t be infuriating – indeed, on occasions he almost seems to relish being just that. But the rhythm of life feels timeless, and Daya in fact appears in better health than ever.

Resist any easy parallels to The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel: Bhutiani directs with great subtlety, drawing out nuances that barely need to be verbalised (if a screen association is necessary, there are resonances with Alexander Payne’s Nebraska). The budget of Hotel Salvation can’t have been large, but the director and his cinematographers Michael McSweeney and David Huwiler relish the different contrasts of light on stone and water, as well as the bright colours of place and attire. Hotel Salvation is a film of great tenderness, one that relishes the details of physical reality, even while acknowledging that leaving all behind is the most natural, even essential thing of all.

Overleaf: watch the trailer for Hotel Salvation

Add comment