Paris, 16 March 1960 – and cinema ruptured. The first public screening of the 29-year-old Jean-Luc Godard’s debut feature, A Bout de Souffle, breathed life into an arthritic medium, announcing a new world of possibility.

Its story, of a French petty criminal (Jean-Paul Belmondo) who kills a cop and goes on the run with his pretty young lover (Jean Seberg), was deliberately drawn from the Hollywood films Godard and his fellow critics at the magazine Cahiers du Cinema had consumed with monastic devotion in post-war cinématèques. But its execution liberated.

In its first few minutes, the smooth, invisible procession of shots that made Hollywood features seem such unquestioned imitations of life was smashed: establishing shots were ignored, points of view contradicted, jump-cuts jerked the audience to attention, till Belmondo seemed to fire a bullet into space, and a policeman fell dead from the opposite direction. What Godard called “the miracle of montage” showed the potential hiding between each frame, making films existential, not inevitable. His young characters were just as heedless.

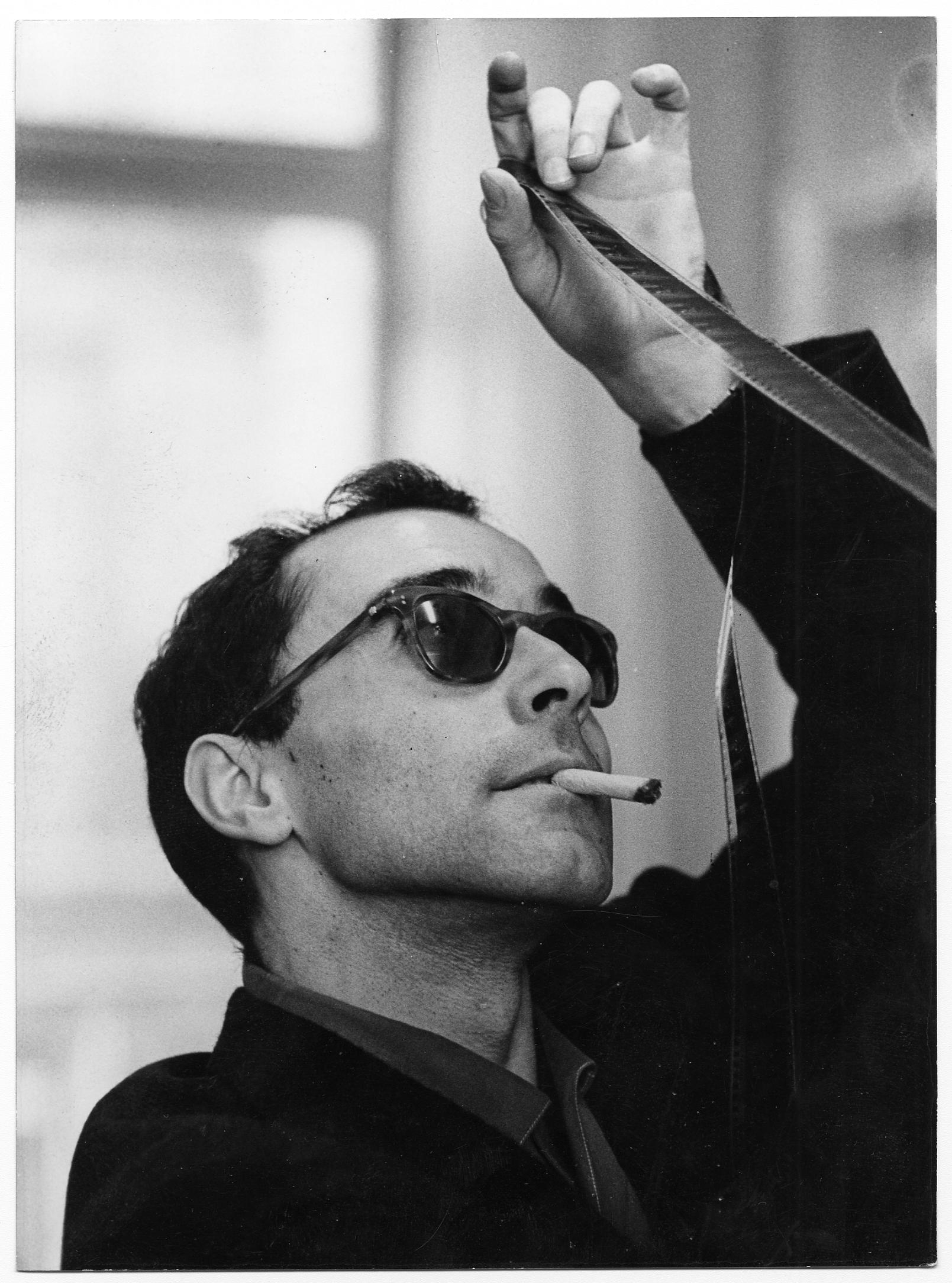

Later, Godard would play down what he’d achieved. He would explain how he had wanted to make an ordinary film, but that it had changed in his hands, and would accurately point to American precedents such as the jerky cuts of Robert Aldrich’s brutal noir Kiss Me Deadly (1955). But such provisos were swept away in the nouvelle vague’s torrent, as he and his less iconoclastic peers – Truffaut, his chief friend and rival – shook old Hollywood itself, Bonnie and Clyde and Easy Rider absorbing torn techniques and setting anti-heroes on their own rebel rampages. Bunuel declared Godard “made anything possible”. Bertolucci said “we all wanted to be” him. In his suit and shades, he was a laconic, iconic auteur, riffing a manifesto which offered cinema as “truth, 24 times a second".

Later, Godard would play down what he’d achieved. He would explain how he had wanted to make an ordinary film, but that it had changed in his hands, and would accurately point to American precedents such as the jerky cuts of Robert Aldrich’s brutal noir Kiss Me Deadly (1955). But such provisos were swept away in the nouvelle vague’s torrent, as he and his less iconoclastic peers – Truffaut, his chief friend and rival – shook old Hollywood itself, Bonnie and Clyde and Easy Rider absorbing torn techniques and setting anti-heroes on their own rebel rampages. Bunuel declared Godard “made anything possible”. Bertolucci said “we all wanted to be” him. In his suit and shades, he was a laconic, iconic auteur, riffing a manifesto which offered cinema as “truth, 24 times a second".

Cinema digested those first assaults long ago, degrading them into MTV. Godard’s Sixties films now seem simply beautiful, playing out in cheap Paris apartments or sun-glazed climes with the gorgeous objects of his adoration – most often his first wife and star, Anna Karina (pictured below, right with Belmondo, then below with Jean-Claude Brialy). In his version of a musical, Une Femme est une Femme (1961), cuts jump, the soundtrack is switched off, and Karina is filmed as a flighty goddess. Le Mépris (1963), tracing a screenwriter’s studio corruption, was his most popular film thanks to the ravishingly nude Bardot. This early work is shocking now for its characters’ space to breathe. It has the freshness of a filmmaker who feels absolutely free. Godard lost that innocence in the late Sixties. His second film, Le Petit Soldat (1960), had been about the Algerian War, but taken no clear side; Pierrot le Fou (1965) had seen Belmondo and Karina play-act Vietnam. But Godard’s second wife and star, the Maoist Anne Wiazemsky, hardened his attitude when they met in 1967. That year’s apocalyptically anti-capitalist Week End began with a corpse-strewn traffic jam, and ended with guerrilla warfare. May 1968 came soon after, student riots on A Bout de Souffle’s breezy Paris streets bringing brief belief that street and cinema revolutions could fuse, and succeed.

Godard lost that innocence in the late Sixties. His second film, Le Petit Soldat (1960), had been about the Algerian War, but taken no clear side; Pierrot le Fou (1965) had seen Belmondo and Karina play-act Vietnam. But Godard’s second wife and star, the Maoist Anne Wiazemsky, hardened his attitude when they met in 1967. That year’s apocalyptically anti-capitalist Week End began with a corpse-strewn traffic jam, and ended with guerrilla warfare. May 1968 came soon after, student riots on A Bout de Souffle’s breezy Paris streets bringing brief belief that street and cinema revolutions could fuse, and succeed.

Godard and Truffaut helped shut down the Cannes Film Festival in student solidarity that year. Yet like Sartre, who fell off his bike en route to a French Resistance mission, returning to writing Being and Nothingness with relief, Godard’s hard-line stance could be softly dilettante in practise. Touring a feature about a Maoist revolutionary cell, La Chinoise, through Californian campuses in 1968 showed him America’s schismed reality, and shook him badly. Sharing a stage with Hollywood directors who’d inspired him, they turned their backs on this French Communist. He told students he preferred Chaplin to Bonnie and Clyde and couldn’t man a barricade: “I am so short-sighted, I would kill all my friends.” The young radicals stared stonily back, leaving him shot by both sides. Invited to another counter-cultural summit when he filmed the Stones recording in London, he tried his best to obscure the making of “Sympathy for the Devil” in One Plus One (1968), a fractured, seminal and faithfully dull account of the Stones in the studio. A serious motorbike crash in 1971 was a further symbolic severance from the 1960’s easy hopes. The multi-media artist Anne-Marie Miéville was his third and last personal and creative partner by now. For the next decade, Godard largely abandoned narrative cinema for semi-documentary, often collective Marxist tracts. In 1974, as budgets and distribution dissolved, he switched to video. “I came from a very rich family,” he said, reflecting on his apparently willed failure, “and that protected me from success. Because success is corrupting. For me, the way to succeed was to be unsuccessful, but to make a living at that.”

A serious motorbike crash in 1971 was a further symbolic severance from the 1960’s easy hopes. The multi-media artist Anne-Marie Miéville was his third and last personal and creative partner by now. For the next decade, Godard largely abandoned narrative cinema for semi-documentary, often collective Marxist tracts. In 1974, as budgets and distribution dissolved, he switched to video. “I came from a very rich family,” he said, reflecting on his apparently willed failure, “and that protected me from success. Because success is corrupting. For me, the way to succeed was to be unsuccessful, but to make a living at that.”

Still, it was perhaps for reasons of self-preservation (he reputedly attempted suicide twice near the end of this futile self-exile) that he returned to star-studded narrative cinema with 1980’s Every Man for Himself (Sauve Qui Peut (la vie)), with Natalie Baye and Isabelle Huppert. Over half a million French cinemagoers turned out to celebrate. But a Chernobyl-haunted deconstruction of King Lear (1987) with Norman Mailer, Woody Allen and Godard himself among the prankish cast, was more typically baffling. Like Brando’s later self-destructive, almost satirical career, the contrast with his popular pomp seemed profound. The 21st century found Godard in a second exile, an apparent recluse relishing the Swiss lakes’ peace, not protest’s tumult. Still with Miéville, he spent his days hunched over video machinery, as if being consumed by the medium he loved. “I never read Marx,” he told an interviewer ruefully. “I am older, and more tired. I’m solitary, guilty, melancholy.” To another, the Godard who’d been cinema’s god mused: “I’ve got some kind of security. I can film christenings, marriages, football matches…”

The 21st century found Godard in a second exile, an apparent recluse relishing the Swiss lakes’ peace, not protest’s tumult. Still with Miéville, he spent his days hunched over video machinery, as if being consumed by the medium he loved. “I never read Marx,” he told an interviewer ruefully. “I am older, and more tired. I’m solitary, guilty, melancholy.” To another, the Godard who’d been cinema’s god mused: “I’ve got some kind of security. I can film christenings, marriages, football matches…”

But he was far from spent. Godard’s last decades passionately raged against cinema’s dying light, while elegiacally acknowledging his own. Histoire(s) du cinéma (1998), taking 10 years to make and more than four hours to watch, was a runic, sprawling meditation on the 20th century and cinema, collaging and overlapping imagery and meaning, burying and praising everything he loved.

The now 80-year-old enfant terrible’s enduring idealism and bitchy spite saw him dismiss his more conventional and beloved nouvelle vague peers Truffaut and Chabrol’s work in a 2004 interview, sighing: “This was not the cinema we had dreamt of.” That year’s Film Socialisme showed that Godard (pictured with Patti Smith) remained a cinema revolutionary, willing it to wake to its potential. He replaces narrative this time with sections centring on an ocean liner, a rural petrol station and great, allusive chunks of old film. Themes include Palestine, the 20th century and its genocides, Jews, Hitler and Hollywood. The whole film sometimes seems a mournful, furious farewell to the conflicts and desires that defined Godard’s post-war generation.

That year’s Film Socialisme showed that Godard (pictured with Patti Smith) remained a cinema revolutionary, willing it to wake to its potential. He replaces narrative this time with sections centring on an ocean liner, a rural petrol station and great, allusive chunks of old film. Themes include Palestine, the 20th century and its genocides, Jews, Hitler and Hollywood. The whole film sometimes seems a mournful, furious farewell to the conflicts and desires that defined Godard’s post-war generation.

His alertness to the 21st century is first shown in achingly beautiful HD video footage of the blue of the sky and shimmering waves. The flapping of shipboard flags escalates into overwhelming noise resembling a wind-ruined mobile phone line, intercut with bad phone-camera footage so overloaded it sounds like thrash-metal, and the ghostly fuzz of people glimpsed on CCTV. Though Godard isn’t online, Miéville finds footage of funny kittens so he can riff on YouTube. Jarring breaks in sound and vision put our unconsidered internet experience on the big screen, giving cunningly edited import and dignity to our digital day, even as Godard ruthlessly dissects it.

The section at a rustic French garage has the intense sense of place of his first films, making you feel the languid midday heat as cars buzz off-screen. The family who live there, including a young boy in a Communist T-shirt who barks, “Make fun of Balzac – I kill you!” could have wandered in from his primary-coloured, playful late Sixties scenarios of agitprop and slapstick. Four years later, Goodbye to Language made 3D a dazzling illusionist’s trick, moving one 3D lens and not the other to make a man and woman overlap and morph, and our eyes scrabble for coordinates on a screen restored as a blank slate of possibility, scrawled on by Godard the 83-year-old conjuror. Ravishing images in sometimes saturated colour – hands sinking themselves clean in a leaf-strewn pool, the looming snout of Godard’s dog, a river, a breast – meanwhile couldn’t look more real. The film drew laughs for sheer chutzpah, and in the manner that Georges Méliès had elicited gasps at cinema’s birth.

Four years later, Goodbye to Language made 3D a dazzling illusionist’s trick, moving one 3D lens and not the other to make a man and woman overlap and morph, and our eyes scrabble for coordinates on a screen restored as a blank slate of possibility, scrawled on by Godard the 83-year-old conjuror. Ravishing images in sometimes saturated colour – hands sinking themselves clean in a leaf-strewn pool, the looming snout of Godard’s dog, a river, a breast – meanwhile couldn’t look more real. The film drew laughs for sheer chutzpah, and in the manner that Georges Méliès had elicited gasps at cinema’s birth.

Godard’s sense of wonder and fascination with the moving image’s evolution was tempered by the political, social and romantic ennui of a May ’68 veteran in 2014, dourly declaring of the smartphone era: “What they call images are becoming the murder of the present.” The Image Book (2018) then mined and elevated Middle Eastern cinema for an anti-colonial last work, haunted and enraged by the Holocaust, ISIS, Israel-Palestine, and cinema’s inadequate response. The medium where he had learned life had failed to save it.

These last works were at once fearsome and impishly hilarious, didactic and suffused with deep melancholy at human violence, as he aged, almost alone; when his great nouvelle vague contemporary Agnès Varda tried to visit him at the end of her film Faces Places (2017), he wouldn’t see her. But he kept connecting images, as if the answer lay just ahead, if he just dug deeper into cinema’s matrix. For all his last testaments’ rigours, their sensuality also typified his life’s work. By now, you could believe seeing film was how he experienced touch.

Godard at the end loved cinema as much as when he fell hard for it, sitting wide-eyed every day in the cinématèque next to his then-friend Truffaut. That’s obvious from his final works’ sheer beauty. “Think hard what you fight for you might obtain it” goes one Film Socialisme subtitle. This stubborn rebel fought to the last. Let his work wash over you, dreaming what film may yet be.

Add comment