It doesn't take much to get lost in a film by Miguel Gomes. In fact, it's required. Multiple layers, timelines, and perspectives unfold in his cinema is mysterious ways, allowing the Portuguese director to tackle the themes that interest him: great love, colonialism, chance, destiny, death, and a dreary Portuguese world that is by no means willing to let anyone take away its history – or its stories.

From the African romance-cum-colonial critique Tabu (2012) to the folk fable allegory of Portugal's financial crisis in his Arabian Nights trilogy (2015), Gomes frequently challenges the boundaries between past, present, and future, raising questions about the forces that contribute to his country's socio-economic struggles. There's invariably a political subtext concerning inequality in his artistic choices. His storytelling is ironic, playful, jammed with cultural-historical references, and intermittently melancholy – the stuff of tragicomedy. (Pictured below: Miguel Gomes)

Grand Tour, his latest, is ostensibly set in 1917-18, but time is a fluid construct in Gomes's work. At its centre is the fictional story of a British colonial diplomat, Edward (Gonçalo Waddington), who is stationed in Rangoon. On what was to have been his wedding day, he flees his longtime fiancée, Molly (Crista Alfaiate), setting off across Southeast Asia with the redoubtable Molly in hot pursuit.

Grand Tour, his latest, is ostensibly set in 1917-18, but time is a fluid construct in Gomes's work. At its centre is the fictional story of a British colonial diplomat, Edward (Gonçalo Waddington), who is stationed in Rangoon. On what was to have been his wedding day, he flees his longtime fiancée, Molly (Crista Alfaiate), setting off across Southeast Asia with the redoubtable Molly in hot pursuit.

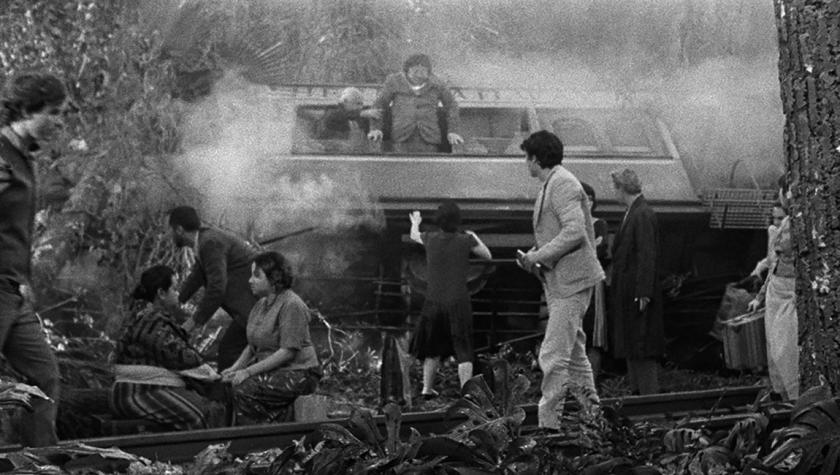

They are filmed in black and white, like characters in silent films and screwball comedies; the places they visit are introduced with mostly colour documentary footage that is no less significant than the vintage-style narrative.

In the spring of 2020, Gomes and his crew travelled through Myanmar and Singapore via Thailand, Vietnam, the Philippines and Japan, literally getting ahead of their two protagonists and filming as they went. Yet Grand Tour is less a travelogue than a free-flowing meditation on different realities.

It earned the now 53-year-old Gomes his first invitation to the Cannes Film Festival last year and won him the Best Director Award. Afterwards, he sat down to talk about capturing the real world and the gracefulness of human gestures on film.

PAMELA JAHN: The title of your film refers to a travel route through Asia that was popular in the early 20th century. How did you learn about this trip?

MIGUEL GOMES: I read William Somerset Maugham's 1930 travel book The Gentleman in the Parlour, which inspired me to make the film. During the British Empire, many writers travelled this route, which began in old Burma or India and usually ended in China. Before we [Gomes and co-writers Telmo Churro, Maureen Fazendeiro, and Mariana Ricardo] wrote the script for Grand Tour, we went on a discovery tour through the area ourselves, working with small local production companies in each country. The writing came afterwards as a reaction to the experiences of that trip, and to the material we recorded there.

Did you know the different parts of Asia?

Not at all, which is why it was important to travel there first. We shot most of it ourselves, except for the footage in China. In February 2020, we were in Japan planning our next trip when our Chinese partners told us there was a problem, and we couldn't enter the country because of the COVID outbreak. At first, we thought it would be over in a few months. After almost two years, we decided to shoot from a distance.

How did that work?

We had a Chinese crew on site, and I was in Lisbon in a house with two or three other people, surrounded by monitors. On one screen, I was looking at what the assistant director captured with the camera on his mobile phone to get an idea of the surroundings. The other screen showed the perspective of the 16-millimetre camera. I whispered instructions to the cameraman virtually. Although I had never met him in person, it worked surprisingly well; I was able to direct almost as if I were sitting right next to him.

What was it that you're trying to capture in those images?

Of course, not being physically present and unable to see things with your own eyes is extremely limiting. The main criteria for deciding where to shoot and what kind of events to film were always determined by my personal interest. What fascinates me? What images do I find appealing? The men pulling boats upstream on the Yangtze River, the Ferris wheel in Rangoon, the picking of lotus flowers in Thailand. I wanted to capture the real world, which consists of highly diverse things, a kind of montage of attractions. Reality is often more spectacular than the fictional imagery created in the studio. (Pictured below: Crista Alfaiate as the jilted Molly)

Would you describe yourself as an ethnographic filmmaker?

Would you describe yourself as an ethnographic filmmaker?

Chris Marker is, of course, a point of reference for me. And before him, Robert Flaherty, who invented a lyrical way of staging reality with films like Nanook of the North [1922]. I'm interested in filming people who do things that are different from what I see around me in Lisbon. For me, filmmaking means leaving my everyday life behind and embarking on an adventure. I try to capture something that surprises me, moves me, and touches me in different ways.

With the love story between Edward and Molly, you add a fictional dimension to the adventure.

I liked the idea of a man who panics before his wedding, flees into the distance, and is pursued by his fiancée. He is a melancholic lost soul. She is the energetic driving force with a goal. In my films, I always try to establish this dialogue between parallel worlds that are equal: the existing reality out there, and the world of cinema, which I deliberately keep artificial because I don't want to fool the viewer into thinking they are seeing reality. Quite the opposite.

The mix of fictional elements and documentary images in Grand Tour creates another level of consciousness.

The worlds should be like opposites, past and present, inside and outside, artificial studio lighting and unpredictable weather. At the same time, there are always connections and overlaps on the visual and audio levels. For example, when I stage a post office in Saigon one hundred years ago in the studio, it is reminiscent of the exoticism of a Hollywood film from the 1940s. Then I cut to a shot of a real post office in the city, which is now called Ho Chi Minh City. These images resonate with the connection between the present and the colonial heritage, and also with how much our view of this region is shaped by classic American cinema, films such as Josef von Sternberg's Shanghai Express (1932), for example.

Why did you choose to use both black-and-white and colour images?

Purely for practical reasons. We shot on analogue 16mm black-and-white film, which isn't sensitive enough in dark lighting conditions. When you're filming at night, it's very difficult to get it to look good or even to see anything at all. We shot those scenes on much more light-sensitive colour film and planned to convert them to black and white in post-production. However, we soon grew tired of this homogeneity, so my editor and I experimented with the original colours and found the contrast very beautiful. But there was no fixed principle, no strict concept. The appearance of colour does not follow any narrative or symbolic logic, it was intuitive and unpredictable.

Your films are often described as magical. What does that mean to you?

To me, magic means to capture grace. I see it as my duty as a filmmaker to find a certain grace in the world and capture it. Like, grace in people's gestures, when they eat, when they sleep, whenever they do something without thinking about a camera.

Has this process become more difficult for you with social media being such an integral part of daily life?

Cinema is quite different. Of course, things changed a lot from the beginning. And there was probably a moment when the audience was more naive and less cynical than they are now. But even today, you can still decide to believe. You make a pact with fiction. You can be moved by puppets. Or by the image you see on screen. It's your choice, always.

Add comment