Krzysztof Penderecki's Polymorphia for 48 string instruments dates back to 1962, and still stands as one of the grand milestones of the avant-garde. It epitomised the Polish composer's technique of "timbre organisation", in which the plucking and bowing of strings was merely a small part of an astounding array of effects.

"I had to develop some new techniques to produce this kind of sound, using different kids of vibrato," Penderecki explains, down the phone from Kraków. "Using the tailpiece to play on with the double basses and celli, also playing directly on the bridge using the highest possible pitch. Of course, I used micro-tonality also in this piece. Maybe even now it still sounds scary to some people, but it was a new sound."

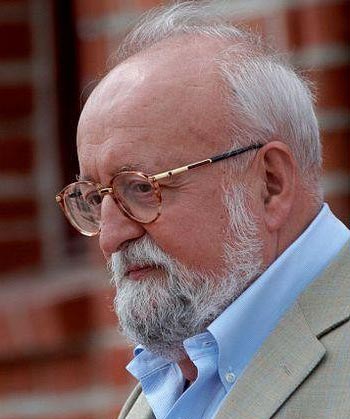

Yet one of the most startling moments in Polymorphia arrives at its conclusion, where Penderecki deploys a massive C major chord. Its outrageously lush and resonant tonality stands in stunning contrast to what has gone before. "It was a kind of solution, or catharsis may be a better word," the 78-year-old composer (pictured below) reflects. "For some people it was very unexpected. For some of my colleagues, very avant-garde composers of the 1960s, it was impossible to use tonal solutions."

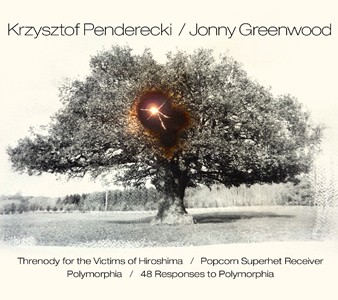

It was from this C major chord that Jonny Greenwood, Radiohead's guitarist and BBC composer in residence, began when he composed his 48 responses to Polymorphia. It will be performed at the Barbican Hall this week by Poland's AUKSO Chamber Orchestra, along with Penderecki's Threnody for the Victims of Hiroshima and Greenwood's Popcorn Superhet Receiver. All these pieces also appear on a new Nonesuch CD.

It was from this C major chord that Jonny Greenwood, Radiohead's guitarist and BBC composer in residence, began when he composed his 48 responses to Polymorphia. It will be performed at the Barbican Hall this week by Poland's AUKSO Chamber Orchestra, along with Penderecki's Threnody for the Victims of Hiroshima and Greenwood's Popcorn Superhet Receiver. All these pieces also appear on a new Nonesuch CD.

"Penderecki told me that he'd written Polymorphia backwards, and had started with C major," Greenwood explains, as we drink tea in his management's offices in Abingdon. Now 40, he still sports his familiar luxuriant mop of black hair, atop a face sculpted with striking architectural boldness.

"Some people say it's a joke or a big controversial ending, and it certainly is a surprise," he continues. "He played it to me at his house in Poland, and it was funny because it was like somebody playing you their demo tape. All the way through he kept saying things like 'these should be a bit louder here' or 'you can't quite hear what the violins are doing here'. The fact that he was still so keen and interested to get it across properly was really cool."

Greenwood's objective was "to write 48 very short pieces of music all starting with C major, and just distorting the chord in different ways. But that started to feel like an exercise more than music-writing, so instead it all started to focus on this Bach chorale style that has lots of C major chords in it, and just various distortions to that. Penderecki was talking about how he used to study electronic music in Warsaw, and I think he realised that all these sounds could be made with an orchestra, or could be done better and developed with an orchestra, so he turned his back on the electronic stuff and went instead to an orchestra, which I still think is a very modern thing to have done."

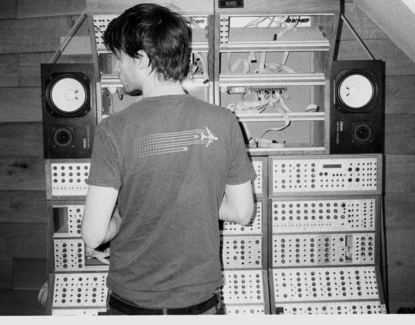

Penderecki can affirm that Greenwood's account sums up his journey through experimental electronica pretty accurately (Greenwood at the controls, pictured below).

"The music is very much inspired by electronics. I went to Warsaw to work in an electronic studio, I think it was 1957, and I fell in love with electronics which was for me the terra incognita, because I never heard such sounds. Of course the equipment at that time was very primitive and very simple, because Poland didn't have much contact with the Western world. But this was a great inspiration for my later music and these pieces were not directly, but kind of, transcriptions from the electronics, from their abstract sounds to sound made by live musicians. I wrote three pieces, the Threnody for the Victims of Hiroshima, Polymorphia and the Canon for string orchestra and tapes. I was very young and rebellious. I was rebelling against my professors of course because they were writing very academic music, and I really wanted to do something unexpected."

"The music is very much inspired by electronics. I went to Warsaw to work in an electronic studio, I think it was 1957, and I fell in love with electronics which was for me the terra incognita, because I never heard such sounds. Of course the equipment at that time was very primitive and very simple, because Poland didn't have much contact with the Western world. But this was a great inspiration for my later music and these pieces were not directly, but kind of, transcriptions from the electronics, from their abstract sounds to sound made by live musicians. I wrote three pieces, the Threnody for the Victims of Hiroshima, Polymorphia and the Canon for string orchestra and tapes. I was very young and rebellious. I was rebelling against my professors of course because they were writing very academic music, and I really wanted to do something unexpected."

Greenwood was first rocked by Penderecki's revolutionary approach to orchestral writing when he heard some of his work during a brief stint of studying music at college just before Radiohead signed to EMI in 1991. He then met the composer after a concert of his music at Drapers' Hall in London "in 1993 or '94, just to shake his hand and say thank you for coming to London. I was a star-struck fanboy, basically. I remember thinking it must be an electronic concert, because where were all these sounds coming from? But it was just a string orchestra playing. I was thinking I'd been sold a lie, and a room full of strings could do far more than I knew, and far more than recordings let on as well (Greenwood at the piano, pictured below).

"After that nothing happened until last year, when a Polish promoter got us together. I went to Penderecki's house to talk about the European Congress of Culture festival in Wroclaw [where a Penderecki-Greenwood programme was first performed last September]. I think they expected me to do a laptop-style remix of one of his pieces, but instead I wrote the Responses to Polymorphia."

"After that nothing happened until last year, when a Polish promoter got us together. I went to Penderecki's house to talk about the European Congress of Culture festival in Wroclaw [where a Penderecki-Greenwood programme was first performed last September]. I think they expected me to do a laptop-style remix of one of his pieces, but instead I wrote the Responses to Polymorphia."

It's hard to know how Greenwood's compositional style would have developed if he hadn't felt the impact of Penderecki, but his musical horizons have been expanding steadily since he became the BBC's in-house composer in 2004, having been offered the post by Radio 3 controller Roger Wright. Popcorn Superhet Receiver was his first composition under the auspices of the BBC, and was premiered by the BBC Concert Orchestra in 2005. Prior to that Greenwood had composed the soundtrack for the movie Bodysong (2003), featuring brass and string quartet alongside electric instruments, and smear, a piece for orchestra and ondes Martenot. He'd first discovered the ondes through its use in Messiaen's Turangalila Symphony, though that wasn't the only place where he'd heard it.

"I remember liking the music from the TV series Flambards, do you remember that? " says Greenwood. "It was sort of like Downton Abbey but set around early aviation in the 1920s. I listened to the theme tune from a YouTube clip and it was all ondes Martenot. I didn't remember that at all, and it was really shocking to hear that again. But I remember reading a description of the instrument - this was at school before the internet existed - and I had to look it up in encyclopedias and it said 'played with a ribbon'. I couldn't imagine what it would look like.

"Then when Radiohead were recording Kid A in Paris we managed to get hold of one. It arrived in a box and I remember just before I opened it thinking 'I have no idea what this is even going to look like except that there's a ribbon'. And it isn't a ribbon, it's a piece of string that's just called a ribbon in French. How do I play it? It was one of the most exciting boxes I've ever opened, I think. It was new, it was a student model they briefly made during the '90s, and it just sounds great."

"Then when Radiohead were recording Kid A in Paris we managed to get hold of one. It arrived in a box and I remember just before I opened it thinking 'I have no idea what this is even going to look like except that there's a ribbon'. And it isn't a ribbon, it's a piece of string that's just called a ribbon in French. How do I play it? It was one of the most exciting boxes I've ever opened, I think. It was new, it was a student model they briefly made during the '90s, and it just sounds great."

Aside from his new music commissions, Greenwood has been carving a swathe through movie-land as an increasingly prestigious composer of film scores. He made a huge splash with his score for Paul Thomas Anderson's There Will Be Blood in 2007, which starred Daniel Day-Lewis as the predatory oil baron Danny Plainview in the Southern California oil boom of the early 20th century.

"The quandary with writing film music is how boring does it need to be, and how interesting would be too invasive?" ponders Greenwood. "It's a problem. Paul Thomas Anderson is weird because when he uses music he uses it. It's rarely bubbling along quietly underneath dialogue, it's just deafeningly loud or there's no music for 20 minutes."

So the music's like a character that sometimes appears?

"Yeah, it's a three-way thing. It's how it's filmed, it's the story and it's the music and they're all as important as each other for those few minutes. That sounds banal now that I've said it, but that's how it is I think."

Greenwood has subsequently written music for Norwegian Wood and We Need To Talk About Kevin, while Anderson has commissioned him again to write music for his forthcoming flick The Master, whose narrative is based around a Scientology-like movement called The Cause. Happily for Greenwood, his rock-star-turned-composer aura seems to have freed him from having to work in the traditional Hollywood way, tailoring his music minutely to every twist and jump-cut of the cinematic action.

"I met all these film composers at a charity concert and they were all very sweet and very encouraging, but reading between the lines - though this might be my paranoia - I got the feeling they were thinking they could write that kind of music if they were allowed to, but they're quite constricted and their job is very difficult and has to provide a service, and it sounds like it sounds because that's what the director wants. I'm lucky because I'm trusted and I can pretty much do what I want, and it's received as though it's really good and important and will work in the film."

"I met all these film composers at a charity concert and they were all very sweet and very encouraging, but reading between the lines - though this might be my paranoia - I got the feeling they were thinking they could write that kind of music if they were allowed to, but they're quite constricted and their job is very difficult and has to provide a service, and it sounds like it sounds because that's what the director wants. I'm lucky because I'm trusted and I can pretty much do what I want, and it's received as though it's really good and important and will work in the film."

The lure of the movies must be difficult to resist, and Greenwood notes wryly that film writing has "led me astray from doing proper grown-up commissioned work." There's a part of him that hankers, quaintly and a little nostalgically, for the life of a jobbing composer and arranger, writing the kind of functional music the BBC Concert Orchestra plays.

"I wrote this piece Doghouse for the BBC Concert Orchestra, that was basically about the orchestra and their history. I find very evocative that idea of all this live music that was written on paper and just stored in the BBC music library. Most if it is forgotten about or was just written as incidental music. All the Wally Stott arrangements and radio themes and the idea of a jobbing orchestra, all these cigarette-smoking musicians in the Fifties, that's what they did for a living. And TV theme tunes, like Ronnie Hazlehurst's music for Yes Minister. The main orchestral music that my generation grew up with would have been theme tunes, for sure" (Greenwood and Penderecki take a bow, pictured below).

So can we look forward to the new light orchestral sound of Radiohead?

"On every album we've ever done I've said we must get an orchestra or some string players in and do it at the beginning instead of the end, but we've never quite managed it for all sorts of reasons. But I'm very keen to do some Radiohead stuff that starts on paper, I think that would be really interesting. We have done a few things. There was the song Harry Patch (In Memory Of) [about the last surviving British soldier from the World War One trenches]. That was written for strings, and Thom [Yorke] sang it live with an orchestra. More stuff like that I think would be really great to do."

"On every album we've ever done I've said we must get an orchestra or some string players in and do it at the beginning instead of the end, but we've never quite managed it for all sorts of reasons. But I'm very keen to do some Radiohead stuff that starts on paper, I think that would be really interesting. We have done a few things. There was the song Harry Patch (In Memory Of) [about the last surviving British soldier from the World War One trenches]. That was written for strings, and Thom [Yorke] sang it live with an orchestra. More stuff like that I think would be really great to do."

Is Radiohead really still a band, or a kind of ongoing organic process? (asks the interviewer, pretentiously).

"I think it's a band because all the best stuff happens when there's three or four of us playing together in a room," says Greenwood. "We think of ourselves as arrangers, I suppose, and we'll use whatever instruments or technology we can to make that arrangement work. It's never 'it's time for my guitar solo now', it's what puts the song across and doesn't fuck it up too much. Even if it does relegate one of us to playing something ridiculous, because it just sounds right."

- Greenwood/Penderecki play the Barbican Hall on Thursday 22 March

- Krzysztof Penderecki/Jonny Greenwood is out now on Nonesuch

Watch video of an orchestral performance of Greenwood's Norwegian Wood Suite

Add comment