theartsdesk Q&A: Sarnath Banerjee | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk Q&A: Sarnath Banerjee

theartsdesk Q&A: Sarnath Banerjee

Graphic novelist from India takes on Che Guevara in Africa

Saturday, 13 March 2010

When the subversive graphic artist Sarnath Banerjee won a MacArthur grant he opted "to research the sexual landscape of contemporary Indian cities", embroiling himself in the aphrodisiac market of old Delhi and introducing the English reading public to the great Hindi word swarnadosh (erm, "nocturnal emissions"). Banerjee (b. 1972) is generally credited with having introduced the graphic novel to India. Incorrectly, as it happens; but with Corridor (2004) and The Barn Owl’s Wondrous Capers (2007) – over and above his work as illustrator, publisher and film-maker – the Goldsmiths-trained Delhiite has more than made his mark on the rampant Indian art(s) scene.

He calls his hectic and unapologetically tangential novels “syllabi of what might come”, and any encounter with him consists chiefly of trying to work out which line of thought he is chasing at any given time (a mutual acquaintance referred to Banerjee as being “permintox”).

He calls his hectic and unapologetically tangential novels “syllabi of what might come”, and any encounter with him consists chiefly of trying to work out which line of thought he is chasing at any given time (a mutual acquaintance referred to Banerjee as being “permintox”).His art works (a misleading self-portrait, left) are highly sought after by young wealthy collectors in India, and following exhibitions at the ICA, Oxo Tower, in Berlin, Stuttgart and Turin, in 2008 Banerjee became the first Indian artist to have a solo exhibition at the Frieze Art Fair, a sell-out series called The Jaguar Salesman (which germinated in his own experience of flogging high-end motors in Bermondsey).

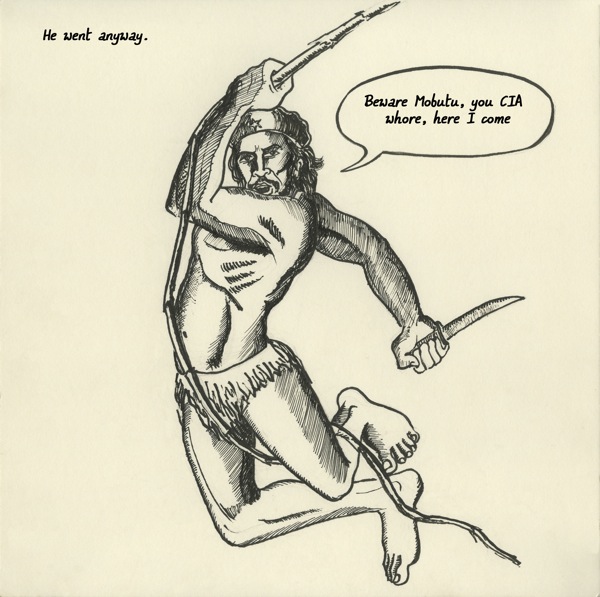

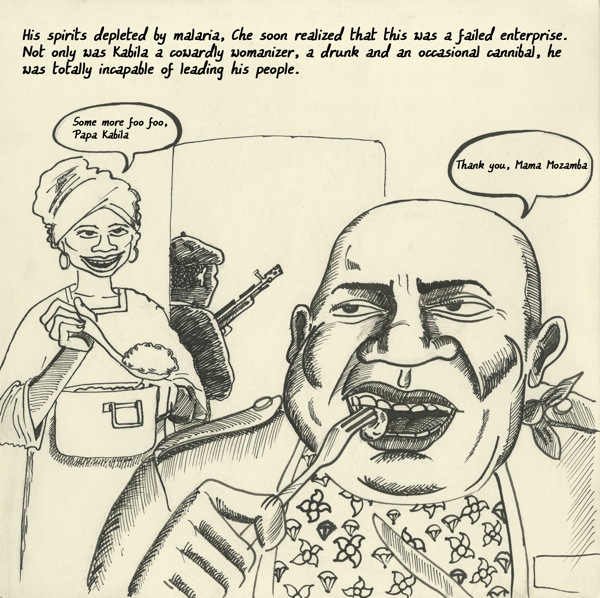

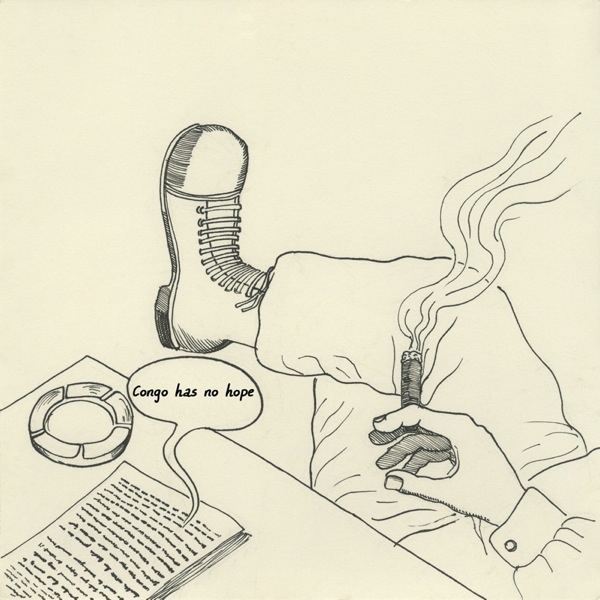

He’s now in Aicon Gallery’s cross-cultural Royale With Cheese show – alongside Ashish Avikunthak, Debnath Basu, Simon Bedwell, David Blandy, Shezad Dawood and Simon Linke – displaying an eight-piece graphic narrative drawn (so to speak) from the Congo diaries of Ernesto "Che" Guevara. Sarnath Barnerjee talks to theartsdesk about Grand Legumes, New Rich Indians, and why El Che’s African experiences shed light on modern-day South Asia. The interview includes images from the exhibition - see the complete narrative here on theartsdesk.

A S H SMYTH: Tell us how your pieces come to be in Aicon’s London show.

SARNATH BANERJEE: Well, I was in London recently, and the Director of Aicon [Niru Ratnam] – he’s a real cool cat, convincing, very charming, very colourful history – he kind of convinced me to be in it. Generally with South Asian galleries my guard is up, specially the ones where NRIs hang out.

New Rich Indians?

Non-Resident. But Niru has given it a very international swing. And I know the brothers who run the place. They’re dudes. One’s an architect in New York.

You’re not comfortable with South Asian galleries [Aicon was formerly called Gallery ArtsIndia]?

I pride myself on my South Asian identity, but I’m not sure I want to be classed as a "South Asian". I’m uncomfortable with the fact that these things need to be geographically defined. The brothers are sufficiently "local" – Indian – for this not to feel like a problem. But basically the NRI market is just not for me. I know the kind of art they buy: decorative, canonical, modern. I have absolutely no patience for that kind of thing. I’m not traditionally Indian in the aesthetic sense. Everybody has his own aesthetics; but mine are a bit… wonky.

So why the Che story? And why Che in Africa?

So why the Che story? And why Che in Africa? Really, Che is just an excuse. It’s more about the middle-class men who run revolutions and a bored man who wants to get back in the papers. And about revolution itself as a fetish. This is my excuse to take on a world in which some day soon there will be riots in Zurich sponsored by Orange, or some bottled water company.

“Revolution as a fetish”?

Ah… It’s an attempt to understand a new brand of political writers and artists. Politics is very much the thing at the moment, and working in politics has become very sexy among artists. Everyone’s politically informed these days – you only have to click on the Huffington Post – but there’s a difference between being politically informed and being politically astute. Politics has been cosmeticised. Remember when Iran suddenly became the new fashionable conversation on Twitter or Facebook or whatever? In my stories I try to make things more complex.

You’re commenting on cliché in political art?

Well, I wouldn’t want to say that: it’s too much of a generalisation, even in my part of the world. There is a certain amount of naivety that has crept into political art. But Pakistani artists, for example, are very good at addressing political questions gently, naturally. There’s a tendency towards lightness.

Indians don’t do lightness?

In India it’s disproportionately commercial. Indian artists are doing very well. Which is not bad; but Pakistan is not yet "discovered" in that way, and that has a definite advantage.

Che in Africa is an overtly political tale, though?

I wouldn’t force politics into my work if it didn’t fit naturally; but, yes, the Che story is obviously political. Politics is like body-odour: if you’re a political character, it will come out! I don’t try to cover my tracks, or hide my political views. But I try to keep it oblique. If people miss it, that’s fine: the one work could be taken as satire, ethnography, a political piece. With age you start reading things in different ways – but the work stays the same.

How else is your work different from the South Asian mainstream?

My work is fundamentally narrative, so I work on the cusp of literature and art. It can get a bit lonely in the art world, working in narrativity: this whole thing about endings versus closure. The writing world is very conservative when it comes to art practices and the South Asian art world doesn’t spare much time for literature. Trying to rollerblade between these two worlds can be quite dodgy!

There’s also a major emphasis on beauty in South Asian art at the moment. It’s funny how a large section of artists have been moving towards decoration. William Morris would be the toast of our art scene today! My method is to do the reading, researching, rendering – then bring in the lightness. The Che story, for example, is obviously not supposed to be comprehensive. It’s not supposed to simplify, either, but to hint at larger complications.

There’s also a major emphasis on beauty in South Asian art at the moment. It’s funny how a large section of artists have been moving towards decoration. William Morris would be the toast of our art scene today! My method is to do the reading, researching, rendering – then bring in the lightness. The Che story, for example, is obviously not supposed to be comprehensive. It’s not supposed to simplify, either, but to hint at larger complications. I’m very interested in the disreputable men of history, especially the Big Men in Africa – the leaders known as the grandes légumes. Mobutu, Nkrumah, Bokassa, Kabila… even Ian Smith. I love these colourful characters. They have a strange patriarchal benevolence, but masking a terrible personal cruelty. The Rumble in The Jungle versus Rwanda.

You have experience in Africa?

I went to Kinshasa to do a graphic thesis on child-soldiers and sorcerors in Central and West Africa. But misery is very banal, after a point. I found I was further fetishising it, and realised I am not a Washington Post journalist and wasn’t going to write brilliantly about it. So I couldn’t complete the book. Instead, I wanted a colleague to stand for election so I could follow him around and create art-work for him. Politics in Africa is extremely colourful – and extremely funny. Intelligent witty people, but they have this uncomfortable relationship with power: they’ve always been subjugated or corrupted by it. I thought putting someone in the possibility of power would reveal a lot about him, and about Africa – over and above the poems, speeches, dancing, posters and the crazy ideas about how to solve Congo’s problems. All good hard art stuff.

And this isn’t some post-colonial shit. They’re crooked buggers, same as we are. But their imagination works in a completely different kind of way. I still think like a third-world person. I grew up in India’s non-aligned era: brothers-in-arms with Bulgaria and Egypt. I hold on to that. It makes my life easier when travelling: helps me become a local more easily.

You can become local, wherever?

My work is not India-centric. I’m a complete Africa slut. I’ve been to places much "further out" - I was in São Paulo before, doing a graphic study of the city, interviewing judo silver medallists and husband-and-wife detective agencies - but in Africa everything made sense. Through Congo and Angola you understand the whole world. The Cold War was actually fought there. And I grew up with Brezhnev and co. They’re like my own circle of friends. Travelling there was like getting my childhood back. You go to a different place and you find yourself in a different time.

“Come to Addis and feel seven years younger”?

Right. Factories in Azerbaijan look like Germany in the Seventies. Actually, the former Soviet Union has lots of big vegetables, too.

Did Aicon commission the Che story?

No, I don‘t do commissioned work, actually. The last one I did was a year ago, for a very fancy magazine called Beaux Arts. Never say never, but for now I can live without having to do commissions. In my head there’s this meta-commission: all these bricks in a very large building! But the Che pieces are new. Very new. I was literally drawing the last lines moments before they came to pick it up!

Will it be exhibited elsewhere after London?

I don’t know about touring. If it sells then I suppose not. If it sells, though, I think I’d like to put it in a book of short pieces I’m working on at the moment, called the Harappa Files. It’s a sort of opium-smoker’s ethnographic survey of contemporary India, told through file entries. A distorted mirror for viewing society and yourself – you are a distorted version of yourself, and of what you perceive. Harappa reveals that part of Indian society that suffers from under-confidence. Little details, like the guy who still views London as the centre of civilisation because they have drinkable tap water, and is distraught to discover that middle-class people there drink bottled water same as in India. Or Tata buying up Jaguar, amidst big headlines of how we, India, have reached the top. These captains of India Shining are complete twats: the sort of conservative, narrow-minded people you made fun of at school.

When you frame your work in art, though, it frees you from having to tell a complete story. The Che series, for example, doesn’t really inform – beyond the fact of his being in Africa – but in a book version it might become even less informational. More representational. But the story casts an interesting light on India, so if I can work it in, I will.

When you frame your work in art, though, it frees you from having to tell a complete story. The Che series, for example, doesn’t really inform – beyond the fact of his being in Africa – but in a book version it might become even less informational. More representational. But the story casts an interesting light on India, so if I can work it in, I will.What does Che in the Congo have to say about India?

India is seen as this very settled place. We have these simple discourses. There are serious issues, of course – Maoists in the East, economic disparity – and sometimes it’s like a country being torn in two parts; but these are not openly discussed. The Che story sheds light on that fetishisation of the idle, "stable" society. There’s a Punjabi word which means "to go looking for trouble just to make your life more exciting".

A gap year?

Exactly! So you travel to experience the world, and end up reinforcing your middle-class prejudices. Like Che going to Africa. It’s a phantom link; but then links of that nature are always inside the head.

You mean Che’s project was a failure?

Yes.

- See the complete eight-scene Che in Africa narrative here on theartsdesk.

- Royale With Cheese continues at Aicon Gallery, 8 Heddon Street, London W1 until 3 April

- Sarnath Banerjee's website.

- Find Banerjee's graphic novels on Amazon.

- 'Farewell to spice and curry' The Hindu Literary Review on new Indian writers

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Bogancloch review - every frame a work of art

Living off grid might be the meaning of happiness

Bogancloch review - every frame a work of art

Living off grid might be the meaning of happiness

Do Ho Suh: Walk the House, Tate Modern review - memories are made of this

Home sweet home preserved as exquisite replicas

Do Ho Suh: Walk the House, Tate Modern review - memories are made of this

Home sweet home preserved as exquisite replicas

Add comment