The battle for Balanchine | reviews, news & interviews

The battle for Balanchine

The battle for Balanchine

ARCHIVE Daily Telegraph, Sat 22 July 2000: New York City Ballet chief Peter Martins defends his controversial stewardship of the world's greatest modern ballets

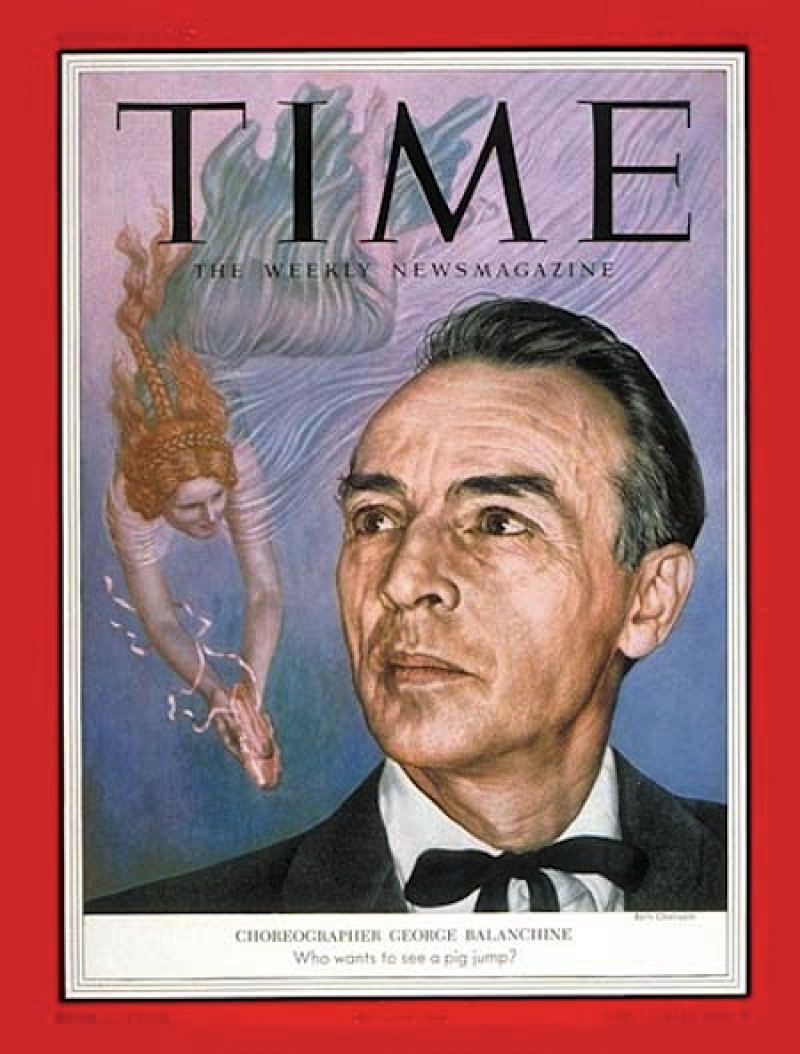

THE choreographer George Balanchine died on April 30, 1983, aged 79, of Creutzfeldt-Jacob disease, a rare, if nowadays notorious, condition only discovered at his autopsy. What had been recognised long before his death, though, was that this man was one of the very greatest geniuses of the 20th century, a figure to be reckoned alongside Pablo Picasso in art and Igor Stravinsky in music.

What he did for ballet was nothing less than complete reinvention, applying his mind energetically for almost 60 years to turning the conventional art he had learned in St Petersburg at the Mariinsky Theatre into something more dangerous, exploratory, pernickety, propelled by his passion for music and curiosity about movement, rather than by storyline or character. A Balanchine ballet needed no clothes other than practice leotards, and no circumstances other than a bare stage and some musicians.

“Balanchine was by no means perfect - he was just another human being. But when it came to making ballets to scores, he got pretty damn close, in my estimation. If you took music as his premise, and then saw his choreographic response, it doesn’t get much better.” That is the opinion of Peter Martins, Balanchine’s successor as director of his company, New York City Ballet, and one of the most personally criticised men alive.

“Balanchine was by no means perfect - he was just another human being. But when it came to making ballets to scores, he got pretty damn close, in my estimation. If you took music as his premise, and then saw his choreographic response, it doesn’t get much better.” That is the opinion of Peter Martins, Balanchine’s successor as director of his company, New York City Ballet, and one of the most personally criticised men alive.

During Balanchine’s life, after he arrived in America in 1933, the company he and his visionary patron Lincoln Kirstein founded, and which he used as both his orchestra and laboratory, had a uniquely formidable reputation. Other companies were known by their star dancers; New York City Ballet was known by its genius choreographer and his super- fast, super-challenging ballets pivoting on racehorse ballerinas of quick wits, rangy glamour and modern sophistication. City Ballet became America’s flagship, the symbol of modern art, nearly twice as rich as New York’s classical company, American Ballet Theatre. (This year’s $45million budget is over three times the Royal Ballet’s.)

If classical ballet had been like the Parthenon, Balanchine ballets had the vertiginous, airy impossibility of a Calatrava bridge

Neo-classicism was the name given to Balanchine’s style: unmistakably classical in derivation and vocabulary, he pushed it, tilted it, speeded it up, evolved it towards a physical expression of the mind, rather than a representation of direct emotion. Bodies that in classical ballets bent or soared to tell of a lover’s pain or happiness, instead followed the sound of a clarinet or the percussive rhythm of a new piece of Stravinsky. Legs and arms that in the past traced lyrical waves and illusions in the air now celebrated articulated joints and gravity games: extreme splits, spiky hands, extraordinary balances held up by a fingertip. If classical ballet had been like the Parthenon, Balanchine’s later ballets had the vertiginous, airy impossibility of a bridge by today's wizard engineer Santiago Calatrava. The choreographers Michel Fokine and Frederick Ashton rival him in aesthetic power; but Balanchine not only made many more major ballets than either, he also changed the look of ballet. New York ballerinas are the sprinters of ballet, and their lean, nimble bodies show it.

When such a figure died, the aftermath was probably predictable. “Do I think people go over the top about him? Yes, I think the minute Balanchine died they made him a god,” says Peter Martins. “Some people just can’t accept that he’s gone.” It’s the kind of dismissive remark for which many people hate him.

There are plenty of cognoscenti in the USA who believe Martins is making a bad job of honouring the god, regularly saying so in print and on the internet, describing him as a man of little taste and much ambition. There are others who argue that he has in fact done well by both Balanchine and ballet itself, his energy shown by the 100 ballets performed in the 50th anniversary season last year, and his refusal to allow NYCB to become a museum company - which would have been anathema to Balanchine himself.

All that will be seething under the surface of New York City Ballet’s visit to Edinburgh next month, its first to Britain for 12 years, and its first to Edinburgh for 33. Edinburgh is personal for Martins: it is where he first danced with NYCB, a life-changing experience for the young Royal Danish Ballet guest. As he points out to me, “A whole generation of people in Scotland have not seen Balanchine danced by his company.” And as I have regretfully pointed out to him, Britain was one of the few dance nations not yet wholly conquered by Balanchine’s ballets, preferring dramas to abstract work. So conquest is in the order of the day. At last, Martins hopes, Britain will “get” Balanchine. But will we get the real Balanchine - in terms of his ballets done unsurpassably well, as the great man himself intended them? This is the question.

What I see in New York City Ballet now, apart from a very serious decline of technique, is also a lack of interpretive freedom, which I would call a lack of courage

I WOULD not like to cross Martins in daily life. Meeting him in Saratoga Springs earlier this month - the summer residence of New York City Ballet - I thought him even more formidable as a 54-year-old than he was when videoed in his golden prime as Balanchine’s foremost male dancer. He is still handsome, a 6 ft 2 in Scandinavian blond with an eye-catching Uma Thurman mouth and a deep, imperious voice.

Is New York City Ballet still the best Balanchine company in the world? “Without a doubt, unquestionably,” he growled, blue eyes blazing into mine.

He hasn’t much reason to like critics. Ever since he took over - encouraged by Balanchine - he has been accused by some of the biggest guns in American dance criticism of focusing on weak new choreography at a cost to the care given to performing and understanding NYCB’s crown jewels, its repertory of Balanchine and his brilliant associate Jerome Robbins. Some of the worst reviews attend Martins’ own new ballets, of which there have been more than 60.

Joan Acocella, the eminent critic of the New Yorker, is convinced that Martins has let technique decline, partly through reducing the strictness of the daily class. She also judges that some of his old colleagues - such as the ballerina Suzanne Farrell (Martins’ former partner) and the male star Edward Villella - are proving themselves much better keepers of Balanchine’s flame, mounting ballets in other companies.

“Although Martins’ own ballets are very minor and very dull, that is not his major sin. I think he does his best in that department,” says Acocella pointedly. “What I complain about is what has been done to the Balanchine repertory. What I see in New York City Ballet now, apart from a very serious decline of technique, is also a lack of interpretive freedom, which I would call a lack of courage. The dancer will simply go out and do the steps, in such a way that you think her primary motivation is just not to make a mistake. At Miami Ballet under Villella you see young dancers absolutely exploding on stage... Every single time Suzanne Farrell sets a Balanchine ballet it rises from the dead.

“Martins was an impassive dancer in many ways. But I would make a bargain. If he could get his dancers today to be as technically perfect a classical dancer as he was, I would be willing to accept a measure of impassivity. But since we are getting a decline in technique and a decline in expressiveness, we are getting a bad bargain.”

Dance is physical. Bjorn Borg was the greatest tennis-player of his era. But he wouldn't stand a chance against Sampras

On the contrary, Martins told me in Saratoga; if anything his dancers are superior to those stars to whom they are compared. I asked him about a recent magazine interview in which he dismissed Nijinsky, Nureyev, Fonteyn, even Farrell as lesser dancers than his latest ones. Did he mean it?

“Absolutely. It doesn’t mean that these other dancers were not great, were not favourites of the public, but you know human nature is such that you get sentimental about the past. Dance is physical. Let me give you a comparison. Does tennis interest you? Bjorn Borg was the greatest player of his era, and some would say no one could match him. But he wouldn’t stand a chance against Sampras.”

But dance isn’t sport... “No, but you have to start somewhere. Dance is physical. It is a physical art form.” Another comparison: “You see old films of Nureyev, when he defected, doing Le Corsaire. Spectacular, fantastic. Then 20 years go by and you have Baryshnikov, doing the same repertory. I mean, what a difference. Rudolf was great when he did it but Misha 20 years later far surpassed him. He jumped higher, he turned more, he was cleaner. Now does it make Misha less artistic than Rudolf?”

Of course not, I said, baffled by the clumsiness of the inference. “But he was so - much - better,” he concluded emphatically. “My dancers dance better today than ever was seen before. I don’t just mean more turns, I mean the bodies are better, it’s more defined, it’s cleaner, it’s clearer... I know what Balanchine would have wanted. I worked with him for 17 years. I’m telling you, I’ve said it from day one, and I’ll say it until I’m either kicked out or crawl out: he would be unbelievably thrilled if he could see it now.”

I asked Martins what he thought of the Balanchine-dancing of other companies - those whom critics may prefer. “The first thing I notice in other places is how his ballets are being danced much slower. Then there’s no problem - it’s easy to dance Balanchine. It may be nicely danced, but it’s not what he would have wanted.” His voice and face registered disdain.

The Royal Ballet was carpeted when it tried to sneak a forbidden cast into Apollo. The ballet was embarrassingly cancelled

AROUND the rest of the world, the dancing of Balanchine is heavily policed. If your company does not please the balletmasters of the Balanchine Trust, you will be refused permission to dance a Balanchine ballet. The Royal Ballet was carpeted in 1997 when it tried to sneak a forbidden cast into Apollo. The ballet was embarrassingly cancelled, at the eleventh hour.

NYCB, however, is exempt from this stricture. Peter Martins can cast any ballet exactly as he likes, no matter whether they seem apt or not. It has to be that way, even when Barbara Horgan doesn’t like it. She is now perhaps the most powerful woman in ballet, one of ballet’s top power-brokers, Balanchine’s long-time personal assistant and one of the three main heirs of the 113 ballets listed in his will.

Unhelpfully, he did not leave any of his ballets to New York City Ballet itself, preferring to bequeath them to 14 individuals. Chief among them were his ballerina and fourth wife Tanaquil Le Clercq - with 85 ballets - the ballerina Karin von Aroldingen, and Horgan. Le Clercq was the company’s ravishing star in 1956, when she was cut down at the age of 27 by polio. It paralysed her. Balanchine remained devoted to her for years (haunted by the hideous fact that when she was 15 he had made a ballet for her in which she played a girl crippled by polio). Eventually, though, he divorced her, due to his obsession (at the age of 65) with the 23-year-old Suzanne Farrell. It was perhaps guilt, thinks Barbara Horgan, that led him to make his stricken ex-wife his main legatee.

At any rate, among the legatees, Peter Martins was notable by his absence. He and the company did not know how to interpret this apparent snub - without control over its repertory, NYCB’s future was in danger. Sulphuric rows followed, in which former colleagues and partners-in-art found themselves at loggerheads. Eventually, Horgan and von Aroldingen formed the Balanchine Trust, an organisation that represented the heirs and appointed 40 or 50 dancers as balletmasters to ensure his ballets could be danced properly around the world - but which also gave New York City Ballet a special licence, under Martins, with complete artistic freedom.

Given the interdependency of NYCB and the Balanchine Trust, Horgan admitted she finds herself in a tricky position on the Martins question. “I have seen some very good performances here, and sometimes I’ve seen performances that I think are just ludicrous. But I also think the New York critics are at each other’s throats. The New York Times’ critic, Anna Kisselgoff, supports Peter like a blind person and their seeing-eye dog. Because Anna writes white, the other critics want to write black. And I feel that Anna Kisselgoff has done more damage by supporting Peter than help to him. I’ve said it to her myself.”

Horgan told me she does think that Martins’ bias towards new ballets (the "Diamond Project") is taking energy and focus from maintaining the Balanchine repertory. But she is “pro” Peter “because he’s survived and the company survived. He’s a leader, and he’s worked his tail off.”

She adds that it was Martins who personally prevented Balanchine’s ballets from being exclusively locked up in NYCB, and being available not only to rival American companies but to foreigners, such as the Kirov and Birmingham Royal Ballet.

The NYCB ballet-mistress gets last season’s hangovers, the ones who knew it before, and the ones you have to cast

Unlike Martins, though, Horgan thinks other companies are where some of the most exciting Balanchine dancing is happening. I met her on her return from London watching the Kirov perform Balanchine’s Jewels last month. She was still dazed. “It was phenomenal. And what amazed me was that they had kept it so well since the premiere last November. I saw the ballet master, Yuri Fateev, after the performance and I said to him, ‘I will be indebted to you for life.’ And he said to me, ‘But you don’t understand - it is in my soul’. And I don’t mean to get emotional here - it doesn’t happen to me very much - but ‘soul’. Soul is something Americans don’t have.

“But then again, my ballet masters had gone there with a blank piece of paper. You don’t get that here. Rosemary [Dunleavy, the NYCB ballet-master] doesn’t get a blank piece of paper; she gets last season’s hangovers, the ones who knew it before, and the ones you have to cast, and the two minutes you get to rehearse so-and-so in between 12 new Diamond Project ballets and a new Twyla Tharp. I mean, how do you do it?” Horgan ends vehemently.

She is - reasonably enough - not very happy about it. Yet almost 20 years after Balanchine’s death, after quarrels, grudges and compromises, his ballets are formidably well protected for the future. Inevitably they will lose the direct touch with him, and yet - as Petipa’s ballets and Mozart’s operas have - they will survive for future interpreters to explore.

Those involved in this saga need only look in their New York backyard to remind themselves how it could have ended. The Martha Graham Company is bankrupt and dying, its choreographer’s great modern dances now in tragic peril of being lost due to personal differences between dancers and heirs. As other choreographers’ oeuvres face the test of survival - Ashton being the obvious one - we must hope it’s the Balanchine model that’s followed, and not the Graham one.

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Dance

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

R:Evolution, English National Ballet, Sadler's Wells review - a vibrant survey of ballet in four acts

ENB set the bar high with this mixed bill, but they meet its challenges thrillingly

R:Evolution, English National Ballet, Sadler's Wells review - a vibrant survey of ballet in four acts

ENB set the bar high with this mixed bill, but they meet its challenges thrillingly

Like Water for Chocolate, Royal Ballet review - splendid dancing and sets, but there's too much plot

Christopher Wheeldon's version looks great but is too muddling to connect with fully

Like Water for Chocolate, Royal Ballet review - splendid dancing and sets, but there's too much plot

Christopher Wheeldon's version looks great but is too muddling to connect with fully

iD-Reloaded, Cirque Éloize, Marlowe Theatre, Canterbury review - attitude, energy and invention

A riotous blend of urban dance music, hip hop and contemporary circus

iD-Reloaded, Cirque Éloize, Marlowe Theatre, Canterbury review - attitude, energy and invention

A riotous blend of urban dance music, hip hop and contemporary circus

How to be a Dancer in 72,000 Easy Lessons, Teaċ Daṁsa review - a riveting account of a life in dance

Michael Keegan-Dolan's unique hybrid of physical theatre and comic monologue

How to be a Dancer in 72,000 Easy Lessons, Teaċ Daṁsa review - a riveting account of a life in dance

Michael Keegan-Dolan's unique hybrid of physical theatre and comic monologue

A Single Man, Linbury Theatre review - an anatomy of melancholy, with breaks in the clouds

Ed Watson and Jonathan Goddard are extraordinary in Jonathan Watkins' dance theatre adaptation of Isherwood's novel

A Single Man, Linbury Theatre review - an anatomy of melancholy, with breaks in the clouds

Ed Watson and Jonathan Goddard are extraordinary in Jonathan Watkins' dance theatre adaptation of Isherwood's novel

Peaky Blinders: The Redemption of Thomas Shelby, Rambert, Sadler's Wells review - exciting dancing, if you can see it

Six TV series reduced to 100 minutes' dance time doesn't quite compute

Peaky Blinders: The Redemption of Thomas Shelby, Rambert, Sadler's Wells review - exciting dancing, if you can see it

Six TV series reduced to 100 minutes' dance time doesn't quite compute

Giselle, National Ballet of Japan review - return of a classic, refreshed and impeccably danced

First visit by Miyako Yoshida's company leaves you wanting more

Giselle, National Ballet of Japan review - return of a classic, refreshed and impeccably danced

First visit by Miyako Yoshida's company leaves you wanting more

Quadrophenia, Sadler's Wells review - missed opportunity to give new stage life to a Who classic

The brilliant cast need a tighter score and a stronger narrative

Quadrophenia, Sadler's Wells review - missed opportunity to give new stage life to a Who classic

The brilliant cast need a tighter score and a stronger narrative

The Midnight Bell, Sadler's Wells review - a first reprise for one of Matthew Bourne's most compelling shows to date

The after-hours lives of the sad and lonely are drawn with compassion, originality and skill

The Midnight Bell, Sadler's Wells review - a first reprise for one of Matthew Bourne's most compelling shows to date

The after-hours lives of the sad and lonely are drawn with compassion, originality and skill

Ballet to Broadway: Wheeldon Works, Royal Ballet review - the impressive range and reach of Christopher Wheeldon's craft

The title says it: as dancemaker, as creative magnet, the man clearly works his socks off

Ballet to Broadway: Wheeldon Works, Royal Ballet review - the impressive range and reach of Christopher Wheeldon's craft

The title says it: as dancemaker, as creative magnet, the man clearly works his socks off

The Forsythe Programme, English National Ballet review - brains, beauty and bravura

Once again the veteran choreographer and maverick William Forsythe raises ENB's game

The Forsythe Programme, English National Ballet review - brains, beauty and bravura

Once again the veteran choreographer and maverick William Forsythe raises ENB's game

Comments

great article. Insightful