Interview: Heiner Goebbels, on staging strange worlds | reviews, news & interviews

Interview: Heiner Goebbels, on staging strange worlds

Interview: Heiner Goebbels, on staging strange worlds

German innovator in London on brilliant form with the Hilliard Ensemble

First, the name. There’s no family link between the 57-year-old German composer and Hitler’s Doctor Death. This Goebbels cuts an impressive figure. Solidly built, with thick white hair and slightly cherubic features, and speaking fluent English, he’s above all accessible and unpretentious.

In our conversation, which takes place in Berlin, the potentially touchy “name” issue is actually the last one broached, and Goebbels is quite relaxed about it. “It’s not uncommon in my part of south-western Germany,” he explains. “That’s where it’s from.” (Goebbels lives in Frankfurt.) “I did at one stage, once my career had started, think about changing it but felt it was already too late. There’d have been a palaver over why I was changing it, so it was more straightforward to bring no attention to it.”

Dealt with. Heiner Goebbels he remains: one of the most exciting innovators in post-war European music theatre, a pioneering individualist and one-time rock musician; a maker of non-narrative plays, an experimenter in electronics - and, also, unapologetically literary.

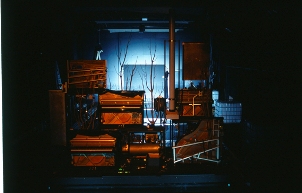

In non-musical quarters, he’s called a theatre director. It’s a fair attempt at a description but too categorical. Goebbels creates musical pictures for the stage, some of them with no human presence. Stifters Dinge (pictured right), from three years ago, was an assemblage of pianos and wires and projections, and a recorded voice, which travelled over pools of water in what, wherever it guested, was a theatre setting; but the 80-minute show was more kinetic art, a beguiling installation, than it was true drama.

In non-musical quarters, he’s called a theatre director. It’s a fair attempt at a description but too categorical. Goebbels creates musical pictures for the stage, some of them with no human presence. Stifters Dinge (pictured right), from three years ago, was an assemblage of pianos and wires and projections, and a recorded voice, which travelled over pools of water in what, wherever it guested, was a theatre setting; but the 80-minute show was more kinetic art, a beguiling installation, than it was true drama.

Goebbels can be bombastic, too. A 1996 piece, Black on White, featured, for no particular reason, brass mutes becoming skittles and musicians throwing tennis balls at a metal sheet, yet the whole thing was eerily wonderful - and it’s hard to say why. Ditto 2004’s Eraritjaritjaka (pictured below left - an aboriginal word roughly the equivalent of “nostalgia”); the lone actor, André Wilms, left the theatre and, followed by a video camera, took a taxi to a flat. There, he chopped an onion. In front of a screen which showed this, a string quartet played Ravel. A year before, Goebbels’s Landscape with Distant Relations - a favourite of mine - opened with musicians and singers dressed in black and huge, magnificent 17th-century white ruffs, for no apparent, historically relevant purpose.

How odd is his work? It certainly never entertains just for the sake of entertaining. His latest piece, I went to the house but did not enter, premiered at 2008’s Edinburgh Festival, and has since visited the US and various cities in Europe. Its arrival on 28 April at London’s Barbican Centre marks a final port of call in an intensive two-year world tour, with breaks.

How odd is his work? It certainly never entertains just for the sake of entertaining. His latest piece, I went to the house but did not enter, premiered at 2008’s Edinburgh Festival, and has since visited the US and various cities in Europe. Its arrival on 28 April at London’s Barbican Centre marks a final port of call in an intensive two-year world tour, with breaks.

“We’ve done about 50 shows,” says Goebbels, “so that’s 15,000 to 20,000 spectators to date. Oddly, the only place where there was a problem for me was in Edinburgh! I was completely distracted by noise from below the stage, where there was a café or something, and I heard a door banging, right the way through, 120 times. It was agony. I went to the house but did not enter requires, in my view, hermetic silence.”

It is, indeed, quiet and undemonstrative, and to that extent a significant change from many of Goebbels’s earlier, noisier shows. Divided into three tableaux, it consists of texts by TS Eliot, Maurice Blanchot and Samuel Beckett (with a short interlude from Franz Kafka) put to a shimmering, a capella score sung by the four male voices of the Hilliard Ensemble.

While singing, the men also act, quietly, neatly, throughout: dismantling a room and putting it back together again in the first part (to Eliot’s “The Love Song of J Alfred Prufrock”); occupying and performing domestic chores in a house in the second (to Blanchot’s The Madness of the Day); watching old holiday footage in a hotel room in the third (to Beckett’s Worstward Ho). It rather resembles a medieval triptych, with the delicacy and detail that come with such a votive artefact, though Goebbels's work, if often spiritual, is never formulaic or preachy.

Did the singers take kindly to his methods? “The Hilliard Ensemble had never worked theatrically before. The fact that they hadn’t was the starting-point for the commission. It wasn’t my idea. I have difficulties with the institution of an opera house, for instance, but after Landscape with Distant Relations, I got all these opera requests - which I turned down - but one, in particular, came from some American promoters, to do something specifically with the Hilliard Ensemble: a 20-minute multimedia piece, for them to include in one of their normal programmes.

“I was immediately hooked. Yet I hate this idea of the multimedia cliché - four musicians in front and a big screen at the back doing something with video. I thought, if I want the media to interact, then I need to do more careful work, have more time and develop things in a process. So I said, ‘Yes, I’d love to collaborate with them, but I’d prefer to do a complete evening, not just one bit in a full programme.’”

Asked whether the four Hilliard members helped with the composing, Goebbels’s answer is a crisp “No”. Material evolved in, he says, “a process” - a word he often uses - in which the singers tried things out, discarded ideas and retained others. This surely risked something resulting in just bits and pieces; cards thrown on to the floor, out of sequence. In a 2003 interview with Sir John Tusa, Goebbels admitted he needed to be careful of being thought of as a “collagist”:

“Yeah, I think it's a danger, it's a great danger. The more possibilities you have the bigger the danger is, and I think the more preparation and careful investigation [you do beforehand the better].” In the case of I went to the house but did not enter (pictured right) Goebbels has undoubtedly done his homework, but it demonstrates more than that. He’s clearly a voracious reader. The title, a phrase from Blanchot’s 1949 short fiction The Madness of the Day, is typical of Goebbels’s fondness for indeterminacy - and for somewhat obscure literary figures. (The French experimental philosopher and novelist died seven years ago. So reclusive was he that no known photos of him exist. In one obituary he was described as acting “as though he were already dead”. The author himself always claimed that his “books were posthumous”.)

In the case of I went to the house but did not enter (pictured right) Goebbels has undoubtedly done his homework, but it demonstrates more than that. He’s clearly a voracious reader. The title, a phrase from Blanchot’s 1949 short fiction The Madness of the Day, is typical of Goebbels’s fondness for indeterminacy - and for somewhat obscure literary figures. (The French experimental philosopher and novelist died seven years ago. So reclusive was he that no known photos of him exist. In one obituary he was described as acting “as though he were already dead”. The author himself always claimed that his “books were posthumous”.)

Goebbels’s chosen texts, spanning 66 years of the 20th century, have much in common. Eliot’s 1917 poem is an exploration of an ego stripped of empirical potency: “Shall I part my hair behind? Do I dare to eat a peach?” In the Blanchot, a ghostly story is told but no framework provided. The reader attempts to follow but can’t really enter it. It’s weirdly lucid, but perplexing.

Beckett wrote Worstward Ho, a short, late prose masterpiece, seven years before he died in 1989. Straining at syntax and sense, it coheres, with a subtle musical rhythm, through a quest for a story its perpetrator is almost sure can’t be told - and contains what has become one of Beckett’s most quoted refrains: “Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try again. Fail again. Fail better.”

As he talks, Goebbels evinces a real love for these writers. He responds as acutely to such joshing, subversive texts as he does to the myriad sounds in his head. Why is he drawn to literature?

“Apart from my musical training, there’s a strong visual element in my biography in the visual arts, starting at the age of 16. I also read a lot when I was young, finding a quality of poetic literature in short texts which hadn't been tried out on stage before. I’ve always been less interested in the dramatic texts of theatre than in the little prose inserts in the programmes, or in poems: in non-dramatic literature. I have a tendency to look for the opposite of drama: something focussed away from a single protagonist who might otherwise be there just to mirror the desires of the audience. I’d rather let the audience discover something in a decentralised image.”

Not all his audiences are unanimous in praise. I have it on good authority that one member of the first-night Edinburgh crowd at I went to the house (which I'd seen three weeks before in Lausanne, where it was produced) yelled from circle to stage at the end of the show, “You’re full of shit, Heiner!” Someone else, an editor with over-literalist tastes, complained to me that it was all too much hard work, that “we weren’t given enough help”. Goebbels isn’t in the business of being easy. “I’m attracted to things which don’t have only one meaning,” he says. “When I worked, for over a decade, with Heiner Müller [a dramatist from the old East Germany who died in 1995], and to whom I was very close, he said, ‘You should never nail a text just to one meaning.’ So, for me, a text which offers a certain quality, which you can read, and re-read, and re-re-read, and in so doing discover other levels of open perspective… that’s the most attractive thing.”

Goebbels isn’t in the business of being easy. “I’m attracted to things which don’t have only one meaning,” he says. “When I worked, for over a decade, with Heiner Müller [a dramatist from the old East Germany who died in 1995], and to whom I was very close, he said, ‘You should never nail a text just to one meaning.’ So, for me, a text which offers a certain quality, which you can read, and re-read, and re-re-read, and in so doing discover other levels of open perspective… that’s the most attractive thing.”

“Composer”, along with “director”, are words that frustratingly bounce off this German. Goebbels unleashes in his shows idiosyncratic noise and kinesis that aren't trying to “say” anything; they just “are”. For me, a scene from Landscape with Distant Relations of swirling, skirted dervishes, a bird pattern projected on to their billowing white robes, remains one of the most engrossing stage images of the new millennium’s first decade. I still don’t know why the dervishes or the bird were there.

Goebbels is unique in his - I was going to say “field”, but it isn’t clear to what discipline he belongs. He doesn’t care for the term “music theatre”, preferring for example to call I went to the house a “staged concert”. Goebbels defies convention, but in a manner which persuades utterly, rather than repelling, those who work with him. He’s also unfailingly courteous, and has found working with the Hilliard, all British, eye-, or ear-, opening.

“Until now, I’ve made a point of avoiding the classically trained voice, because somehow I’ve always missed a unique identity there. The Hilliard Ensemble is different. With this group, when they sing together, new territory is gained through the homogeneity of their four voices, and also in the way they bounce off each other. They’ve not wanted to stop I went to the house, in spite of their many commitments elsewhere.” Then, shortly before our chat ends, quite unexpectedly, Goebbels leaps off of his chair. He swings his arms around, and his normally subdued tone rises to shake the Berlin room we’re in:

Then, shortly before our chat ends, quite unexpectedly, Goebbels leaps off of his chair. He swings his arms around, and his normally subdued tone rises to shake the Berlin room we’re in:

“When you work with four actors or four opera singers, you always have someone in rehearsal saying, ‘YOU ARE DOING THIS’ or ‘LET ME PLAY THIS ROLE.’”

He sits down and again speaks normally. Goebbels knows what he doesn’t like. He insists he can only work with performers who're happy, first, to play around a bit, and who then show faith in his curious constructions. He doesn’t like rules. His work is thematically indistinct but always has a precise and formal architecture. He mightn’t be a “collagist”, but he is a builder, a manufacturer of moods and images which shy away from a centre. He’s one of those artists everyone wants to give a name or title to. But none stick.

- I went to the house but did not enter is at the Barbican 28 April-1 May

- Find Heiner Goebbels's recordings on Amazon

- Heiner Goebbels' official website

- Check out what's on at the Barbican this season

Watch a clip from 5 Minutes Too Early/ Three Steps by Heiner Goebbels and Heiner Müller

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Theatre

Not Your Superwoman, Bush Theatre review - powerful tribute to the plight and perseverance of Black women

Golda Rosheuvel and Letitia Wright excel in a super new play

Not Your Superwoman, Bush Theatre review - powerful tribute to the plight and perseverance of Black women

Golda Rosheuvel and Letitia Wright excel in a super new play

Cow | Deer, Royal Court review - paradox-rich account of non-human life

Experimental work about nature led by Katie Mitchell is both extraordinary and banal

Cow | Deer, Royal Court review - paradox-rich account of non-human life

Experimental work about nature led by Katie Mitchell is both extraordinary and banal

Deaf Republic, Royal Court review - beautiful images, shame about the words

Staging of Ukrainian-American Ilya Kaminsky’s anti-war poems is too meta-theatrical

Deaf Republic, Royal Court review - beautiful images, shame about the words

Staging of Ukrainian-American Ilya Kaminsky’s anti-war poems is too meta-theatrical

Laura Benanti: Nobody Cares, Underbelly Boulevard Soho review - Tony winner makes charming, cheeky London debut

Broadway's acclaimed Cinderella, Louise, and Amalia reaches Soho for a welcome one-night stand

Laura Benanti: Nobody Cares, Underbelly Boulevard Soho review - Tony winner makes charming, cheeky London debut

Broadway's acclaimed Cinderella, Louise, and Amalia reaches Soho for a welcome one-night stand

The Pitchfork Disney, King's Head Theatre review - blazing with dark energy

Thrilling revival of Philip Ridley’s cult classic confirms its legendary status

The Pitchfork Disney, King's Head Theatre review - blazing with dark energy

Thrilling revival of Philip Ridley’s cult classic confirms its legendary status

Born with Teeth, Wyndham's Theatre review - electric sparring match between Shakespeare and Marlowe

Rival Elizabethan playwrights in an up-to-the-minute encounter

Born with Teeth, Wyndham's Theatre review - electric sparring match between Shakespeare and Marlowe

Rival Elizabethan playwrights in an up-to-the-minute encounter

Interview, Riverside Studios review - old media vs new in sparky scrap between generations

Robert Sean Leonard and Paten Hughes make worthy sparring partners

Interview, Riverside Studios review - old media vs new in sparky scrap between generations

Robert Sean Leonard and Paten Hughes make worthy sparring partners

Fat Ham, RSC, Stratford review - it's Hamlet Jim, but not as we know it

An entertaining, positive and contemporary blast!

Fat Ham, RSC, Stratford review - it's Hamlet Jim, but not as we know it

An entertaining, positive and contemporary blast!

Juniper Blood, Donmar Warehouse review - where ideas and ideals rule the roost

Mike Bartlett’s new state-of-the-agricultural-nation play is beautifully performed

Juniper Blood, Donmar Warehouse review - where ideas and ideals rule the roost

Mike Bartlett’s new state-of-the-agricultural-nation play is beautifully performed

The Gathered Leaves, Park Theatre review - dated script lifted by nuanced characterisation

The actors skilfully evoke the claustrophobia of family members trying to fake togetherness

The Gathered Leaves, Park Theatre review - dated script lifted by nuanced characterisation

The actors skilfully evoke the claustrophobia of family members trying to fake togetherness

As You Like It: A Radical Retelling, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - breathtakingly audacious, deeply shocking

A cunning ruse leaves audiences facing their own privilege and complicity in Cliff Cardinal's bold theatrical creation

As You Like It: A Radical Retelling, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - breathtakingly audacious, deeply shocking

A cunning ruse leaves audiences facing their own privilege and complicity in Cliff Cardinal's bold theatrical creation

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: Refuse / Terry's / Sugar

A Ukrainian bin man, an unseen used car dealer and every daddy's dream twink in three contrasting Fringe shows

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: Refuse / Terry's / Sugar

A Ukrainian bin man, an unseen used car dealer and every daddy's dream twink in three contrasting Fringe shows

Comments

...