William Hurt, great Hollywood contrarian, has died at 71 | reviews, news & interviews

William Hurt, great Hollywood contrarian, has died at 71

William Hurt, great Hollywood contrarian, has died at 71

A string of brilliant performances cemented his place as a great face of 1980s cinema

No actor had a classier time of it in the Eighties than William Hurt, who has died at the age of 71. Ramrod tall, blue-eyed and aquiline, with a high forehead swept clear of thin fair hair, he was a brash decade's intelligent male lead.

At 38, Hurt had somehow contrived to match the career longevity of a pretty young actress. He did plough on. The Nineties had him in sci-fi, slapstick, romantic comedy, none of them genres that agreed with the cool intensity of his Nordic demeanour. It may also be that the industry as a whole stopped making the kind of films that suited his performing style. There was a touch of the Cary Grant about Hurt, a besuited civility. The all-new buttock-baring leads went to the more animal Michael Douglas.

Even so, pedigree will out. From 2005 Hurt was eye-catchingly cast by David Cronenberg in A History of Violence, by Robert De Niro in The Good Shepherd and Sean Penn in Into The Wild - note that two of those directors are actors. Endgame, a compelling British television drama, found Hurt playing Willie Esterhuyse, apartheid’s intellectual figleaf (pictured right), in an account of the secret negotiations which preceded the freeing of Nelson Mandela. It was perhaps the finest performance of his later years.

Even so, pedigree will out. From 2005 Hurt was eye-catchingly cast by David Cronenberg in A History of Violence, by Robert De Niro in The Good Shepherd and Sean Penn in Into The Wild - note that two of those directors are actors. Endgame, a compelling British television drama, found Hurt playing Willie Esterhuyse, apartheid’s intellectual figleaf (pictured right), in an account of the secret negotiations which preceded the freeing of Nelson Mandela. It was perhaps the finest performance of his later years.

As he nudged into his 60s, Hurt became part of the heartbeat of Hollywood again. He played an evil master controller-type baddie in The Incredible Hulk, and cropped up in Ridley Scott's Robin Hood. There was less hair and more midriff. But the hallmarks of his finest performances were still there: the moral intelligence, that almost physical air of watchfulness, the careful delineation of speech and gesture. When I met him in 2010 he insisted he had never been away - and he would, being a world-class contrarian, and an inimitable interviewee.

JASPER REES: You have always had an unusual quality among leading actors. Does the sense of separateness go back to childhood?

WILLIAM HURT: I lived with my father in Lahore for a year and a half in the late Fifties so that was only ten years after partition. I lived in Khartoum with him in the early Sixties, I lived in Mogadishu with him not too long after the Italians were out of there, before the militants were getting the tribal stuff organised and Ethiopia was not too hot then. I’ve seen a lot of Eastern Africa, when I was a kid when your balls haven’t dropped and you don’t have a passport. They treat you as human. You see an immense amount when you’re young that you can’t see when you’re past puberty because by then you represent something. But before then you don’t. Before then you’re everybody’s kid. Hopefully. Unless things are really bad, which they can be.

So also I grew up in the South Pacific for the first six years of my life. I spoke sentences of Guamanian before I spoke English because we lived there too. I was best friend with guys on dirt floors. And then we were living in Spanish Harlem. I don’t have a problem with poor people. I don’t have a problem with black people. I was living in, on and around them from the time I was a baby. So I didn’t see any difference. I just didn’t see my best friends as black or white. So all those people can go screw themselves. They don’t get it. I’m not a very exciting interview, I’ll tell you that.

Did that homelessness or nomadism in your childhood shape the choice you made you do what you do?

I don’t know how to say in terms of a cause and effect summation. I do know that people completely fascinate me. I really do revel in individuals. Even if you were to offend me tonight, I don’t care. It won’t matter. I will have been studying you the whole time. My bumper sticker was, "I like people, just not in groups."

Does that remain the case?

It’s pretty close. It’s one of my bumper stickers. The other one is "I feel so much better since I gave up hope." People are like "Oh but you’re so despairing!" I’m not despairing at all. I don’t believe in hope. I don’t believe in something I don’t have. I believe in something I can. I believe in fate and I believe in work. I don’t believe in the second car I don’t have yet or the picket fence I don’t have yet or the lottery. It’s all trash. It’s disgusting.

How long have these beliefs need to formulate?

I think they formulated early. The problem was confirming them. Good sense is probably almost everybody’s property. It’s when they get convinced that something else is true that clashes with their good sense. And confirming their own good sense is really the issue in most of our lives. That’s the hard part. But you can get there.

Was becoming an actor good sense?

Yeah yeah. For me it’s been a great choice. But I don’t look at it like a lot of people do. I don’t look at it like being the centre of attention. I really don’t. I had to turn that corner early. For me the first great issue was between acting and acting out and that took about 10 years of careful study. Because if you’re not going to act out you’re standing up against your entire culture. Thinking that you’re the guy.

Did you have to learn that before you made it?

Well, no. Yes of course I did. Because you’re always dealing with that "Am I doing it for them or am I doing it for some better reason? Am I doing it to get attention or am I doing it to pay attention?" That issue starts early. It’s the monumental issue.

All the good actors are doing it for the latter reason?

Any person who is doing anything well is doing it for the latter reason. Anybody who is doing anything halfway decent has enough confidence to pay attention. Which means they talk about something that they’ve been studying and that they would like to share commentary about.

Does this mean that you were a bad actor to start with?

I may still be one! I don’t know.

You’re manifestly not.

I don’t know that. You go ahead. I just do it. I do what I can. And if I’m lucky enough to get an opportunity I do that. I’m glad to have the privilege.

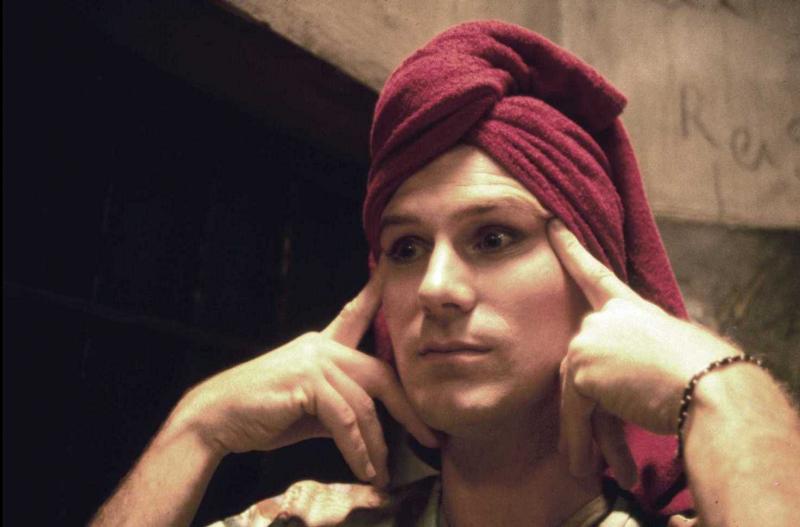

It took a while for you to land that great role in Altered States (pictured left).

It took a while for you to land that great role in Altered States (pictured left).

I didn’t land that role. I fought that role. I tried to not make that movie. I tried to get out of it.

Presumably because of Ken Russell?

No no no. Arthur Penn was the original director. I tried to get out of it because I didn’t want to make movies. I didn’t want to be famous. It’s not good for some people. It hasn’t been good for me. Fame is not a happy condition for me. I’m not looking a gift horse in the mouth. I’m just saying I’m very happy to be allowed to do what I do but there are aspects of fame that are not pleasant.

Such as?

Having people generalise about you with any information about you whatsoever. Contempt prior to investigation. It’s a remarkable prejudice. "Aren’t you who I think you are?" "No, ma’am. I don’t know anything for sure in life except one thing. I’m sure I’m not who you think I am. I’m positive of that. Now can I go my wandering way?" I know that.

How did you get to a point where you were being offered a film that you couldn’t get out of?

What happened with Altered States was I was in an elevator in a building in New York to go to a theatre audition. I was happy. I was doing ensemble repertory work. I was happy.

In New York?

Yeah.

And you were, what, 30?

No no I was 28, 27, 28. I had been to Juilliard when I was 25. Then I had gone working in the regions. That was my home. That’s where they did good work and that’s all I wanted to do. I was an actor happy to live with the truth of acting which is that as you do it it’s gone. The only perfect thing I ever found in acting was it was done and gone. There was a moment and in that moment that was all you were ever going to get. It took me years of real searching to get to the simple fact, that’s what it is. That you pay as much authentic attention to whatever you’re trying to do as you think whoever made you did in creating you, or better. Just try. Of course it’s a futile effort but it’s an idea of an attempt. That’s all it is. So it’s not so portentous and people have to work through their neuroses by thinking things are more important than they are. So that’s why theatre is a very very therapeutic and healthy thing to do if it’s done with that kind of approach. "I’m real, you’re real, we’re here, this is happening. This is what you think and feel. Whatever you think and feel is yours, I’m not going to tell you to think and feel, but I’m going to offer you a dialogue, I’m going to offer you a dialectic. And if you don’t like it, walk out. Really, walk. Fine, good, good. Do it." Everything is the Nike commercial. Do it.

I can’t make movies, because I’m too thin-skinned. I’ll wither under the assault of generalised fame

You did get sucked in to doing a film though?

No no. Not sucked in. What happened was there was a man in the elevator with me and his name was Howard Godfrey and he said, "You’re an actor." I’m going, "Yeah, what do you know about it?" He says, "No no, I heard about you." I said, "So?" He goes, "You’re a good actor, right?" I was, "I don’t know!" He said, "We want to see you for a movie." This guy’s like, you know, he’s probably from the garment district. "He says, ‘I work with Paddy Chayefsky.’" I only knew one person who dealt with film at all in the film world that I respected and that was Paddy Chayefsky.

Paddy Chayefsky owned his own work. No writer owns his own work. They disenfranchised all artists. They started it in the Twenties and Thirties by buying the writers’ work. The first thing they did to de-ball all of us was buy the writer’s work. They can change any word they want to, they can still slap his name up there and they can still say it’s his idea, that he agreed what they did to those words, but he probably didn’t, or she didn’t. So that was the beginning of the disenfranchising of the collaborative effort of theatre. Then they took the director and instead of allowing him to be the facilitator and communicator of ideas, appreciator of talents, they turned him in the hirer or firer and administrator, which is exactly the opposite to his function, and they take the actor and instead of allowing him to transcend through character they turn him into a narcissist personality who has to sell himself out of the box. End of story. Goodbye. Goodbye, theatre. Goodbye, usefulness. Goodbye to work. Goodbye.

So then he says, "I work with Paddy Chayefsky. We’ve been looking for a long time for someone to do this film." I said, "Well, you know I don’t make movies." Because I didn’t. I didn’t audition for movies. Every time I got a call from my agent to audition for a movie I just said no. Because I really knew it was not for me. I do believe that women need nine months and I need six weeks. That’s what I believe.

Did you like going to see films?

Sometimes. Sometimes. I was like, "OK, it’s a movie." Sometimes it was wonderful. Sometimes you saw something great. You saw Man for All Seasons or you saw Mad about Jersey. You saw The Big Knife. I liked them but it wasn’t my thing, it wasn’t what I did. So I said, "Can I read it?" He said, "Yeah you can read it." So I got a copy of this thing and I had been thinking about the beginnings of our current situation, intellectual property in bio-engineering, I had been thinking about computers and all that. And then I read this script and I was in a Cuban coffee shop and I couldn’t stop weeping for about half an hour and I couldn’t stand up for 45 minutes because it was every idea that I had been thinking about. Everything was in this thing.

I knew about Ken Russell. I’d seen his movies. But I didn’t like him personally

You decided to override your own rule then?

No no no, I read the script and went back and said, "I don’t want to make, I can’t make movies, because I’m too thin-skinned. I’ll wither under the assault of generalised fame." I mean it didn’t take a rocket scientist of psychological understanding to get that. I knew that I would not have fun with that. I had fun digging. And he said, "We’ve decided not to make the movie because we can’t find anybody who can play the role, who understands it." I said, "No no no no no, you have to make it. I can’t play it." They’d seen 500 people. And so I said, "Ok ok ok." Paddy had to make it because he’d made Network, he’d made The Hospital, he’d made Marty, he’d made all this stuff. This had to be made because this was the best idea that anybody had had for a long time. This was not a movie, this was great ideas, and those ideas had to get out.

So I had to confirm that they needed to pursue that so that I could give them a little bit of where I came from and then I could go home. So I said to him, "How long will you give me to prove to you that you can make the movie?" He said, "One hour." I said, "Give me two weeks." I took the script away for two weeks, I memorised every word, I worked on the entire structure of the entire thing, every scene. I went in after two weeks. Fifty-nine minutes and 30 seconds later I stood up and said, "That’s why I think you have to make it. And I’m going." Arthur was there and Paddy was there and Howard was there behind a table. They said, "Wait a second." They went in a corner and started talking, I’m waiting and then they’re "We’ll make it if you’ll do it." I said, "I don’t make movies and I really don’t want to." And I was not joking. I’m still not joking. I could be happy without this. I’m not an ungrateful wretch. I’m very grateful for what has been given to me.

So why did you make it?

Because I spent two weeks having dinner three times a week with Arthur Penn figuring out a way for me to get out of film after making one movie. I had no obligations to do PR. I had a guarantee that I was personally in control of the character. I had director approval until 48 hours before we started filming. I had no obligation to market at all. And I had those protections in my contract for many many many years. You couldn’t make me market a film that I didn’t like, that I didn’t approve of. You couldn’t make me sell something where I thought I’d been lied to or cheated or where the promise of something had been deliberately deceitfully lied about. You couldn’t make me smile on something I didn’t want to smile on.

It was on that basis you agreed to do it?

Yes, and I was with Arthur. And on the basis of at least three weeks of full rehearsal. Which Paddy was of course all in favour of because he was an artist.

How did Ken Russell get involved?

What happened, and this is a great mystery that nobody knows about, is that only Paddy knew that Paddy was dying. He had cancer. And what happened was Paddy became afraid that with Arthur’s technique of directing he wouldn’t finish the film in time for Paddy to see it. So he fired Arthur and he got somebody who he thought would finish it faster who in fact finished it slower and with whom he disagreed categorically about his interpretation, thus taking his name off the film. They had a fist fight in the closet on the third day of filming. A full-out full fight in the Italian restaurant. That was my birth into film.

I was working a minimum of 14- to 18- to 20-hour days for seven months. I knew about Ken Russell. A little bit. I’d seen his movies. But I didn’t like him personally. So we were in this little room and there was this radiator and a little desk and a chair and we didn’t sit for a half an hour, neither one of us. Finally he sat on a radiator and I sat on the floor. When he sat on the radiator his pants pulled up and I saw he had Betty Boop socks on. It was then I thought, I’ll do it.

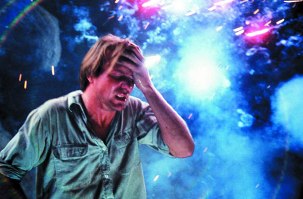

So why did you do another film if that was going to be your one film? What seduced you back in?

So why did you do another film if that was going to be your one film? What seduced you back in?

When I was offered the second film Sigourney Weaver (pictured right) was in it, Chris Plummer was in it, Irene Worth was in it, Jimmy Wood was in it, Morgan Freeman was in it, and it was a lovely little script and they offered me $70,000. And I said, "Oh my God, that’s way too much money." No, they offered me 140. I said, "That’s insane. You take half of that, and this conversation never happened. You take the money and you give it to Off Off Broadway theatre, so that you, Hollywood, are giving something to the garden where you get your flowers, the ones that make your reputation for you, that give you everything you have." Because I knew that that connection didn’t exist. They never fertilised our garden. They refused. They said exactly what Sam Cohn told me in private that they would do. They came back with the following statement: "We would have to redesign our entire accounting system to accommodate your desire." Because it is against their philosophy. Peter Yates was directing it. I gave a lot of that back to theatre. I didn’t need that kind of money. But then you’re getting sucked in. You’re the guy on the white horse now. Why shouldn’t they be subsidising the people who are most important to artistic expression, the ones upon they are basing their success and making their reputation?

So you did that film and you were hooked?

A person doesn’t like to admit that, but maybe.

What came next?

After States came Eyewitness. Then came Body Heat. See, what happened was Larry [Kasdan] and I talked about the structure of an idea for an ensemble working in film on Body Heat. While we were making Body Heat. You think I’m like some film addict? I really don’t think I am. If you haven’t changed the world into what you wanted to change it into, does that mean it was a bad idea? Does it mean you haven’t tried? I’m not responsible for your cynicism about this. You’re trying to get me to admit that I was seduced into something. They were all good films.

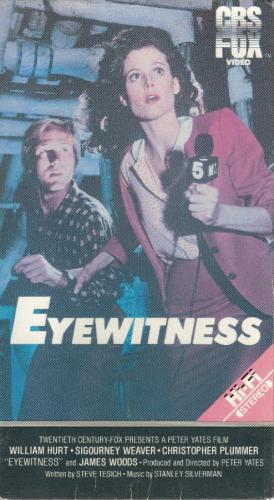

For 10 years you made without exception fantastic films. You were in most of the great films of the 1980s. Body Heat (Hurt with Kathleen Turner, pictured above) was the best structured film I ever read. It was a better structure than States. But I spent the first six hours of my life with Larry Kasdan telling him why he couldn’t direct it. He didn’t know what he had. It was a gem, pure and simple.

Body Heat (Hurt with Kathleen Turner, pictured above) was the best structured film I ever read. It was a better structure than States. But I spent the first six hours of my life with Larry Kasdan telling him why he couldn’t direct it. He didn’t know what he had. It was a gem, pure and simple.

Did he take kindly to that?

Yes he did. He listened. Because I was the only person that was honest with him. He had not directed before. I was simply saying that his odds of pulling off were remote. Which was true. It’s much nicer to be treated with honesty than it is to be treated fatuously.

Has your honesty ever got you into trouble?

Yeah, sure. Sure. Thank God. I hope it gets me in trouble with people who don’t want it.

Did it ultimately have an impact on the kind of films you were able to make?

It’s like when someone says to you, "Go make these big films, then you’ll be given the chance to make the ones you want." I can promise you that if you do that you may make some big ones but by the time you’ve done it you won’t remember how to make the ones you wanted.

What combination of luck and desert was it that ensured that you had a remarkable series of scripts landing in your lap?

They didn’t land in my lap. You read and you found the ones you saw goodness and lightness and structure in. First of all structure.

Was it good taste?

Knowledge. Because I had read Shakespeare, I had read Chekhov, I had read Ibsen, I had acted in Chekhov, I had acted in Ibsen, I had acted in Stoppard, I had acted in Pinter. I had acted. I had acted these things. They were part of my life. It’s not like throwing dice. If someone says "good luck" to you before you go to work, just tell them you’re not going to Atlantic City, tell them you’re going to work. Don’t ratify luck with saying "thank you". I’ve never been sorry about anything I chose to do and I’ve never been sorry to lose one. You know the joke about actors? How many actors does it take to screw in a light bulb? One to screw in a light bulb, and 24 to say, "I could have done that better." Well, I’m not one of those 24. Sometimes I get to be the one. I’m sure there are people who say they could have done and maybe they’re right.

For the whole of the 1980s you were the one. You screwed in the light bulb for the whole of the 1980s.

That’s not how it felt to me. To me it felt like I was doing my job.

You’re being modest.

I’m not being modest. I’m telling you the truth. I’m not being anything. Are you asking me about me or are you telling me what people think about me? It’s a different thing.

I’m telling you my perception. You were in a series of films that all landed. Eventually you won an Oscar and all that.

I was given one. I was handed one.

But after that those leading roles in those films that turned out right and struck a chord with the film-going public seemed to run out.

That’s to you. Because they were, "Well, where’d you go?" I go, "I was there." It’s funny because if you don’t give people what they expect they think you’re failing. What if you know you’ve just done great work and you’re the only one that thinks so? So you’re going to believe them or you’re going to go with what you know? That depends on how you know what you know. If you study for 20 years with people you truly admire who base what they teach you on an empirical process that is completely trustworthy and you trust them, you don’t trust the other people.

So this word that is bandied around in the film industry – heat – is something that you couldn’t give a flying fuck about?

It’s like when someone goes "You’ve got a good chemistry with somebody." "Get out of here. Are you a chemist? Can you fix Aids please?" It’s not the case. You can work well with people whose breath ou don’t like. You have to believe in it. That’s all that counts.

When you had that contract that would absolve you from the need to participate in publicity, what films in those early days did you refuse to publicise?

I’ve always been so careful about that. I always know the first day I’m there I’m there for a reason I want to be there for. Sometimes it was a greater or a lesser risk that it could go the wrong way. A lot of the film this was not in my hands. I mean I did get onto Lost in Space and the guy who is playing the captain, the driver, is suddenly not the black man you were told it was going to be but it was a white man who they just put in the role. And you’re going, "Well, at least we were making this thing that was for racial diversity." And they’re going, "Well, we’ve decided that the quotas are such and such." "But that's a kind of betrayal." "Sorry, you’ve got your contract. We do what we do." That’s not in your control. I outlined how Hollywood took the art away from the artist.

When are you going to write a book about this?

I might write a letter to my kids. I mean like about a 400-page letter.

Not for publication.

It’s for my kids. How am I going to explain? I mean either Wellington or Napoleon said, "Never apologise, never explain." It’s kind of important which one but I can’t confirm which one. You do what you do.

How good a film was The Big Chill (soundtrack album pictured left)?

How good a film was The Big Chill (soundtrack album pictured left)?

It was almost a classic but not.

What was stopping it?

What stopped it was that Larry - who is a brilliant man, for me one of the five best people I’ve ever known in my life, certainly one of the great artists... The Ladd Company had told us that whatever we brought as a next project they would do. So he brought them Chill. And basically they said, "This is too good, no one wants to see it. Goodbye." Which meant that he had to hawk the movie. So hawking the script cost him final cut which is a terrible thing to lose.

What happened in the final cut that he didn’t want?

The coda. Two things about the coda. The coda was after the kitchen scene you went back to the university and you saw them as they had been. Now the whole idea of Chill was to make a film which legislated the requirement for great ensemble work by the way it was written. Which is what Larry and I had discussed on Body Heat. I said the only way you’re going to get it done is by legislating it into the script, because they are never going to do it as an idea. Hollywood doesn't want actors working together. It wants all the talented little insects to jump out of the boxes with their product and do their thing so that the guys who own it can own it forever. And that is how they do own it, by the way. Standard side contract: "in perpetuity throughout the universe", five times. OK? Take a look. I’m the only actor I know who’s even read it. They have total complete control in eternity throughout the universe or in perpetuity throughout the universe. I’m going to throw a bi-constitutional law at that pretty soon. So that it can’t be constitutional.

I don’t know anybody else who asks the DP or operator, "What lens you got?"

So he lost final cut. If it ain’t on paper it doesn’t matter what they promise you. They’re always going to break their promises. Once you lose it you lose it. And I always knew that what was susceptible in the screenplay was the most audacious stroke in it, which was the coda. And as actors we had to prove that we were good enough actors to play ourselves younger than currently. The hardest thing in acting is playing younger. Judi Dench can do it. She’s a master. She can be 70, 17-year-old face, just falling in love, you believe it. But if you’re coaxing New York actors who are trained in theatre for the first time – I was the only one who had done it before... So New York actors go, "If you can do it maybe I can do it."

The line between theatre and film was always one which those of us who had trained in theatre crossed very gingerly. A lot of guys don't make it because they don't understand the time and space abstraction. Eighteen thousand people without a microphone and an 85mm shoved up your nose are different time and space problems. But that’s all it is. It’s an abstraction. Telling the truth is the point. So what you do is understand the metaphor within which you are telling that truth and that’s what becomes your obligation as a skilful person. Accommodate that time and space conventionally. It’s all convention. So I had solved that problem because that’s the way I looked at it. Pure abstraction. "Teach me about that lens. Teach me about that camera." Glass and metal to me. That’s all a camera is. It ain’t 20 million people, it ain’t worldwide fame, it ain’t love. So what does it do? It’s a tool. It’s a paintbrush. I had a buddy who was the operator on Altered States, he would stay up with me till three o'clock, four o’clock in the morning, and he would show me what lenses do, how they change perspective depending on the parabola of the prism, different focal lengths, depth of field. I was just asking him what were the tools here. What have we got? You act within the tool that you have because there is a ratio of activity to frame.

Did you always make a point of knowing what lens you were acting with?

I just ask, "What lens you got?" Sure. I really don’t know anybody else who does it. I don’t know anybody else who asks the DP or operator, "What lens you got?" And I don’t look through. I never look at rushes. I don’t want to look at me. I’m not talking about that. I’m just thinking about space. What’s this space? I don't want the space to be ragged. In all art you have a centre and a periphery and the relationship between the two is what balance is all about. It’s true in this metier as well and you have a right to think about these things. It’s not taboo to think about your metier. These are your tools, so go ahead. Use the sucker. Do something with it. Don’t just let it shoot. The word "shoot" - bad word. The word "cut" - bad word. The word "show" - bad word. The only word is work. Work is the word. Work makes you freer, man. Because it gets you outside of your petty self-conscious insecure self.

That was the phrase used by the Nazis.

I know that. It’s over Auschwitz. That's why I use it. I study that a lot. Since I was 14, I've been studying the Holocaust. One of the jobs which they say wasn’t a big success was when I narrated in English To Speak The Unspeakable by Elie Wiesel when he went back to Auschwitz with a videocam. Black and white, feet crunching on the gravel, ‘This I where I said goodbye to my mother and sister, this is where my father was bludgeoned to death." Well, that wasn’t a big success, was it? But I’m proud of it. So are they right? That I wasn’t a success that day? It wasn’t hot. It wasn’t heat. But I was proud being a part of that. I was glad. I felt like a reasonable human being the day that I worked on that project. And the Academy turned it down because it wasn’t sentimental enough, turned it down for competition. Well, who’s wrong? Who’s wrong? You decide. You hear what I’m trying to say. It is up to you, though.

When they gave me the Academy Award that night I was tremendously conflicted

You have a reputation for being difficult to work with.

"I heard you’re difficult to get along with. I hear that you’re obstreperous. You must be neurotic or temperamental or something worse." "No. No. You’re wrong." "Oh you told me I’m wrong. You are obstreperous." You hear what I’m saying? You can’t win that way. You just do good work. I mean that really is all you can do is just do damn good work.

The thing is that your fellow artists don’t always welcome uninvited opinion.

Not initially. But if they’re given the full monty, if they get six weeks, and they know that within that time you have shown that you are authentic and are taking a back seat to the truth of the play or the film and you believe in their work as much as you believe in your own, if you get a chance to prove that rather than just say it, I’ve never walked away from an actor under those conditions who didn’t appreciate being looked at square in the eye and treated as a human being.

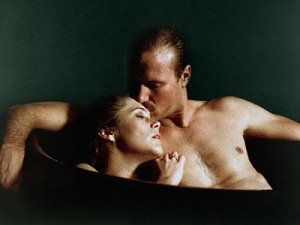

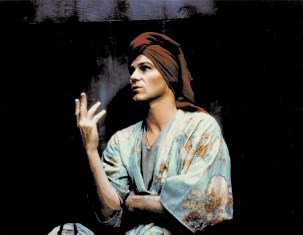

And how about Kiss of the Spider Woman (pictured right)? How good a film was that?

And how about Kiss of the Spider Woman (pictured right)? How good a film was that?

It was written by a saint. I met that guy. A living saint. He was dying of Aids when I met him. An angle on this planet. I met a few. Manuel Puig, amazing man. How good a film is it? It’s a little slow. It’s a good film.

Wouldn’t the stage actor in you like its slowness?

Slow is not my purpose. Why people slow things down too much, I think they’re looking for truth. Once it’s real you can speed it up as much as you want. I’m mean look how fast I’m talking.

Did they give you that Academy Award because it was sentimental enough?

Every award is a standard bearer. But the night that I got mine was also the night they gave one to the producer of 007 for selling more theatre tickets than anybody ever sold. So OK I’m going, "Is this the same statue, is this the same golden dildo they ram down your throat to make sure you never work unconditionally again?" Because I did Spider Woman on spec. They didn’t give me a buck for that movie before they made it.

Why did you make it on spec?

Because it was great.

In terms of looking least like yourself, was that a prime example?

In terms of looking least like yourself, was that a prime example?

It would be one of the obvious examples. The History of Violence (pictured left) is another example. It’s always different. It’s like you’re always wearing a mask. It’s what mask you’re wearing. Which one are you using? The more complete your mask is, whether it’s in flagrante delicto or subtle, the more complete it is in its psychology, the more you see the soul of your own being. That's what masks are for. The key to the mask is that if the mask that you make proves your value, proves that you have been attentive to a human being, then through those dark holes you’re in there. That’s what you want. You want to share that. You want to be in there with others. And that’s a feeling that I can’t describe. I have to do it. I have been there. I have done it. I have participated in moments when that was reached and it is a prize without price. It cannot be quantified. It is a state which is so wonderful, so useful, that you cannot sell that, you cannot buy that cheap. It’s there. It’s among, not about. And that’s why you do it. That’s why I do it. There’s all kind so accoutrements that people are going to judge things by, but that’s really got nothing to do with it.

If you could have your time again would you have not done Altered States?

No no no no. Anything Paddy Chayefsky did I would be a part of.

If you had just done Altered States and gone back to theatre...?

My answer is it’s too late now.

You said fame did not agree with you.

Fame itself, no.

How did it manifest itself, its disagreement with you?

Fame is part of it. Well, look, when they gave me the Academy Award that night I was tremendously conflicted. I thought I was going to get away with it, I thought I was going to put on my penguin suit and have a couple of drinks and go and look at the other salivating guys in the penguin suits and I was going to watch them like you study a character. When they called my name out I really thought, "Oh no no no no, don't put that target on my chest, don't do this."

Wasn’t there a part of you that wanted it?

Yeah sure, there’s always a part of you that wants to be, you know, the so-called best. But when you’re a human being you know that doesn't exist any more. That’s a way to get somewhere and when you get to a certain point you have to set that aside. So I had set that aside. So I was in this game and we did it on spec, I mean we did it for nothing. There was some remuneration later. And I went up onstage and Sally Field whom I knew very well, because we’d done a play together which was broadcast live, she brings it over, and I said to her, "Sally" - this is the words I said to her, onstage, she put it in my hand and I said, "Sally, what the hell do I do with this?"

She was famous for having made that acceptance speech the year before.

Yeah yeah yeah. So she had lived with it. She looked at me hard because she knew me – she was a wonderful woman – and she looked back and she said, "You live with it," which was a wonderful response. So I held it, I walked over, and I started living with it. But you know, "Be careful what you want, young lady, for you will surely get it." It’s one of the lines from Chill, as is "He didn’t sell his psyche for a little attention, he was classier than that." Those lines in your work are themes, and they become mantras in your life. And I live with them. It’s like "To be or not to be" or Arthur Miller’s "What is content?" The mantras of your existence. And each role, each piece, has these lines about which revolve all the meanings that you love so well and you make them part of your life. You drink them in. You attach them to your being, to your heart, and you walk and that’s what you walk with from then on. So it’s not about it’s a success or it’s not a success, it’s about walking the walk, man, it’s just about walking.

You can go anywhere with someone who admits what they don't know

And when something happens to you, you can’t say you went out and got an Academy Award. That isn’t the way it works. That's a lot of things that are completely out of your control. For you to claim that it’s anything to do with you finally in the long run... would I be allowed to act if I had a wart on my nose? You couldn’t be president if you had one. You can have an IQ of two or 200,000 and they wouldn’t let you be president with a wart on your nose. So yeah OK, I got this waspy damn face. That’s part of the reason why they let me do it. But does that mean that’s why I do it? Does that mean it has to be my reason. No. No. No, no, that’s not my reason.

How did you get on with Franco Zeffirelli, director of Jane Eyre?

Well, he pissed me off at first, I have to tell you. But we got along after a while OK. He called me to thank him for helping him make a good movie. I haven’t seen him since. But we got along OK after a while after he stopped meddling. It was the English who knew how to make Jane Eyre, not him. When he came in he was a little anxious at first but mostly it’s best to choose good people and let them make the movie. Well, he had great people.

Did you notice things changing for you in any way when your hairline started rising (Hurt in Robin Hood, pictured right)?

Did you notice things changing for you in any way when your hairline started rising (Hurt in Robin Hood, pictured right)?

Yeah, I got a sunburn easier.

I meant professionally.

Do you see any tie-ins? I started looking more like my dad. That’s it.

But the parts change?

Are you asking me, do people stereotype? Yes they do. Have I had relatively good luck in challenging that? Yes. But I also made that good fortune by insisting on doing things that challenged that notion.

How did you get on with István Szabó, the Hungarian director with whom you made Sunshine?

He’s a magnificent man, magnificent artist. He and I walked around Budapest. This is his generosity. I arrived right at the end of a huge production. He must have been completely exhausted. I had this strange feeling when I got off the aeroplane, I had travelled a long way, but I got in the cab, I said, "Take me to the set." And he, imagine this – a director of a film of that complexity at that time of the schedule – just him walking all over Budapest with me, telling me about when his father died. He’s an artist. He likes people. He believes in them. The problem with film is that people think it’s a directors’ medium. It’s not. It’s a collaborative medium. But if you think it’s a directors’ medium, who’s going to stop you?

A lot of directors think that.

I know that. They're wrong. It is a collaborative medium. And the worst ones are the ones who wear too many hats. Any one of those hats would be enough for any genius’s energy. "Who are you to usurp three or four or five hats? You’re a filmmaker? Oh really." What a lot of crap.

Have you never acted in a film in which the director is also acting?

Sure. I’ve acted in a lot of movies. The more load they carry, the more necessary it is for them to do a little saying, "I don’t know." They can say, "I don’t know," you can follow them anywhere. You can go anywhere with someone who admits what they don't know, but if they don't have that basic courage to say, "Well, I don’t know, I’m not sure, what do you think?" it doesn’t mean you can’t get it done, it doesn’t mean you cry and go "boo hoo" and sit in a puddle on the ground. You still have to solve the problem and do the best you can. You got a time limit, you got a money limit. You don't have a love limit.

Explore topics

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Film

One Battle After Another review - Paul Thomas Anderson satirises America's culture wars

Leonardo DiCaprio, Teyana Taylor, and Sean Penn star in a rollercoasting political thriller

One Battle After Another review - Paul Thomas Anderson satirises America's culture wars

Leonardo DiCaprio, Teyana Taylor, and Sean Penn star in a rollercoasting political thriller

Steve review - educator in crisis

Cillian Murphy excels as a troubled headmaster working with delinquent boys

Steve review - educator in crisis

Cillian Murphy excels as a troubled headmaster working with delinquent boys

Can I get a Witness? review - time to die before you get old

Ann Marie Fleming directs Sandra Oh in dystopian fantasy that fails to ignite

Can I get a Witness? review - time to die before you get old

Ann Marie Fleming directs Sandra Oh in dystopian fantasy that fails to ignite

Happyend review - the kids are never alright

In this futuristic blackboard jungle everything is a bit too manicured

Happyend review - the kids are never alright

In this futuristic blackboard jungle everything is a bit too manicured

Robert Redford (1936-2025)

The star was more admired within the screen trade than by the critics

Robert Redford (1936-2025)

The star was more admired within the screen trade than by the critics

Blu-ray: The Sons of Great Bear

DEFA's first 'Red Western': a revisionist take on colonial expansion

Blu-ray: The Sons of Great Bear

DEFA's first 'Red Western': a revisionist take on colonial expansion

Spinal Tap II: The End Continues review - comedy rock band fails to revive past glories

Belated satirical sequel runs out of gas

Spinal Tap II: The End Continues review - comedy rock band fails to revive past glories

Belated satirical sequel runs out of gas

Downton Abbey: The Grand Finale review - an attemptedly elegiac final chapter haunted by its past

Noel Coward is a welcome visitor to the insular world of the hit series

Downton Abbey: The Grand Finale review - an attemptedly elegiac final chapter haunted by its past

Noel Coward is a welcome visitor to the insular world of the hit series

Islands review - sunshine noir serves an ace

Sam Riley is the holiday resort tennis pro in over his head

Islands review - sunshine noir serves an ace

Sam Riley is the holiday resort tennis pro in over his head

theartsdesk Q&A: actor Sam Riley on playing a washed-up loner in the thriller 'Islands'

The actor discusses his love of self-destructive characters and the problem with fame

theartsdesk Q&A: actor Sam Riley on playing a washed-up loner in the thriller 'Islands'

The actor discusses his love of self-destructive characters and the problem with fame

Honey Don’t! review - film noir in the bright sun

A Coen brother with a blood-simple gumshoe caper

Honey Don’t! review - film noir in the bright sun

A Coen brother with a blood-simple gumshoe caper

Comments

I think William Hurt was a