Akram Khan, DESH, Sadler's Wells Theatre | reviews, news & interviews

Akram Khan, DESH, Sadler's Wells Theatre

Akram Khan, DESH, Sadler's Wells Theatre

One man's sentimental journey emits megastar mastery of all his arts

It takes more than utmost craft and rich personality to hold the stage as a soloist - it takes a touch of divine self-belief, which Akram Khan has never displayed to more magnetic effect before than in his new solo DESH. Actually solo is too small a word for this epic, lavish display of the starpower that Khan now emits in the world of dance theatre.

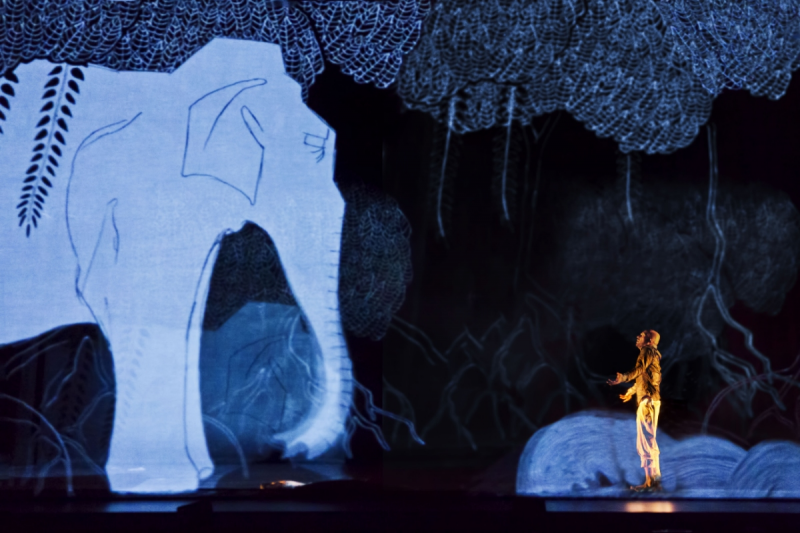

This production looks as if it has cost hundreds of thousands of pounds to stage, with its luxuriously liberal video animations by Yeast Culture, celestial lighting by Michael Hulls, an ambitiously created live/recorded soundscore by Jocelyn Pook with Nicolas Faure and some staggeringly beautiful designing by Tim Yip with Sander Loonen. It’s theatrical scenography on a scale fit for an emperor, which is why there is a faint irony about all this being laid on so opulently for Khan to tell us a story of his rediscovery of his family’s humble roots in Bangladesh.

Still, for almost all of DESH one is whipped along in Khan’s sentimental journey by the magical beauty and mastery with which he shows it. Always passionate about his heritage’s storytelling tradition (and one shouldn't forget that he was a boy actor with Peter Brook 20 years ago), he here narrates and embodies an almost filmic odyssey of storytelling - from the poor cook whose son wants to dance, to the street boy whose life is bludgeoned down by relentless urban oppression, all the way to Khan as himself phoning a call centre endlessly because his iPhone voicemail doesn’t work, and getting a small boy’s voice on the other end.

These are worlds apart which only a man of dual heritage like Khan can know, a child of both London and Bangladesh. His pieces have always been personal, if sometimes solipsistic quests, always of rare skill, but DESH has the magic of honesty and modesty inside its marvellous trappings. Now when he dances, he doesn't just tell his own story - he tells all our stories.

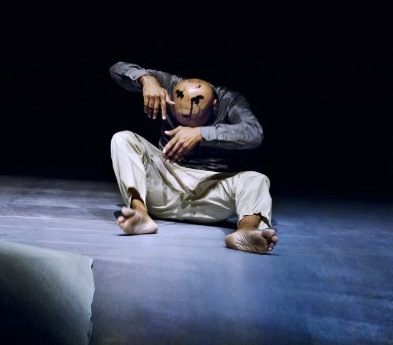

The theme of generational shifts resurges affectingly. A child's voice is heard constantly begging for stories, and Khan himself becomes the child in those stories, running through miraculously animated video woods that ought to be mythical places faraway but which the youngster insists are in Wimbledon Park. Khan comically impersonates the poor kitchenhand, tucking his head into his shoulders to show his bald crown, on which he’s painted eyes and a mouth (pictured right) - it’s very funny, but also odd, disturbing, to see how this reshapes the body into a sickle of pleading, arms outstretched, head ducking, legs buckling.

The theme of generational shifts resurges affectingly. A child's voice is heard constantly begging for stories, and Khan himself becomes the child in those stories, running through miraculously animated video woods that ought to be mythical places faraway but which the youngster insists are in Wimbledon Park. Khan comically impersonates the poor kitchenhand, tucking his head into his shoulders to show his bald crown, on which he’s painted eyes and a mouth (pictured right) - it’s very funny, but also odd, disturbing, to see how this reshapes the body into a sickle of pleading, arms outstretched, head ducking, legs buckling.

He finds fantastical metaphors of lostness, spinning into vortices of sucking light, or whirling in storms of white ribbons. Cunningly, he delivers this with a light touch, whimsical almost, as if imparting serious things to a child without wanting to disturb them. But those eye-blurring spins and falls, the way Khan’s body so often seems at the mercy of galactic gusts and unstoppable forces, as little and resistless as a leaf, those bring out the almost unimaginable lengths to which migrants might hurl themselves to escape being a pot-herd like their dad and become a dancer in the West.

Over this sweet-sour content, Pook's soundscore pours atmospheric sugar and cream, rich fusions of "Alleluias" and "Ave Marias" with minimalist till-readies, Asian folk riffs and rhythms all thrown liberally into a musical food mixer. For years Khan has zigzagged between his Kathak dance tradition and his contemporary London ideas in his productions, but here is a complete merging and subsuming of a complex emotional make-up, guilt, gratitude, tenderness, fear, new fatherhood, filial regrets, in theatre of heartfelt and beautifully achieved urgency.

And he is now, in his late thirties, a great master of all his arts of dance technique and expressiveness, he now picks and chooses anything from classical footwork to catatonic body language, all with absolute integrity to his past, his ancestors and his own path ahead.

So I will rave on for an hour or so but I became creepingly over-conscious of Khan's liking for multiple farewells, starting about half an hour before he intends to leave. Are there eight endings here, or only seven? The hair-raising circular spin into the dark - stunning. The end-of-life crawl to clutch at the pile of mother earth - heartrending. The jolting transformation into a spasmoid, raging street protester - that’s a shock. The dancer whose feet have been flayed by a soldier, leaving him helplessly marooned on his backside - an agony to watch. The terrifying immolation in the rain of white ribbons - unspeakably sad. The upside-down suspension in the air like a celestial body that looks down on earth from divine clouds (pictured above) - and so again goodbye, and again goodbye, and again.

On the other hand, perhaps that's the idea: that there is no one way to take your leave, and say adequately what you wanted to.

- Akram Khan performs DESH at Sadler's Wells until Saturday, then at Kwai Tsing Theatre, Hong Kong, 18-19 November; Concertgebouw, Bruges, 1 December; Les Théâtres de la Ville, Luxemburg, 18 January 2012; Festspielhaus St Pölten, Austraia, 18 February; La Comète, Châlons, France, 9-10 March; MC2, Grenoble, 14-16 March; Stadsschouwburg, Amsterdam 19-20 May; Théâtre de la Ville, Paris, 18-29 December

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Dance

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

R:Evolution, English National Ballet, Sadler's Wells review - a vibrant survey of ballet in four acts

ENB set the bar high with this mixed bill, but they meet its challenges thrillingly

R:Evolution, English National Ballet, Sadler's Wells review - a vibrant survey of ballet in four acts

ENB set the bar high with this mixed bill, but they meet its challenges thrillingly

Like Water for Chocolate, Royal Ballet review - splendid dancing and sets, but there's too much plot

Christopher Wheeldon's version looks great but is too muddling to connect with fully

Like Water for Chocolate, Royal Ballet review - splendid dancing and sets, but there's too much plot

Christopher Wheeldon's version looks great but is too muddling to connect with fully

iD-Reloaded, Cirque Éloize, Marlowe Theatre, Canterbury review - attitude, energy and invention

A riotous blend of urban dance music, hip hop and contemporary circus

iD-Reloaded, Cirque Éloize, Marlowe Theatre, Canterbury review - attitude, energy and invention

A riotous blend of urban dance music, hip hop and contemporary circus

How to be a Dancer in 72,000 Easy Lessons, Teaċ Daṁsa review - a riveting account of a life in dance

Michael Keegan-Dolan's unique hybrid of physical theatre and comic monologue

How to be a Dancer in 72,000 Easy Lessons, Teaċ Daṁsa review - a riveting account of a life in dance

Michael Keegan-Dolan's unique hybrid of physical theatre and comic monologue

A Single Man, Linbury Theatre review - an anatomy of melancholy, with breaks in the clouds

Ed Watson and Jonathan Goddard are extraordinary in Jonathan Watkins' dance theatre adaptation of Isherwood's novel

A Single Man, Linbury Theatre review - an anatomy of melancholy, with breaks in the clouds

Ed Watson and Jonathan Goddard are extraordinary in Jonathan Watkins' dance theatre adaptation of Isherwood's novel

Peaky Blinders: The Redemption of Thomas Shelby, Rambert, Sadler's Wells review - exciting dancing, if you can see it

Six TV series reduced to 100 minutes' dance time doesn't quite compute

Peaky Blinders: The Redemption of Thomas Shelby, Rambert, Sadler's Wells review - exciting dancing, if you can see it

Six TV series reduced to 100 minutes' dance time doesn't quite compute

Giselle, National Ballet of Japan review - return of a classic, refreshed and impeccably danced

First visit by Miyako Yoshida's company leaves you wanting more

Giselle, National Ballet of Japan review - return of a classic, refreshed and impeccably danced

First visit by Miyako Yoshida's company leaves you wanting more

Quadrophenia, Sadler's Wells review - missed opportunity to give new stage life to a Who classic

The brilliant cast need a tighter score and a stronger narrative

Quadrophenia, Sadler's Wells review - missed opportunity to give new stage life to a Who classic

The brilliant cast need a tighter score and a stronger narrative

The Midnight Bell, Sadler's Wells review - a first reprise for one of Matthew Bourne's most compelling shows to date

The after-hours lives of the sad and lonely are drawn with compassion, originality and skill

The Midnight Bell, Sadler's Wells review - a first reprise for one of Matthew Bourne's most compelling shows to date

The after-hours lives of the sad and lonely are drawn with compassion, originality and skill

Ballet to Broadway: Wheeldon Works, Royal Ballet review - the impressive range and reach of Christopher Wheeldon's craft

The title says it: as dancemaker, as creative magnet, the man clearly works his socks off

Ballet to Broadway: Wheeldon Works, Royal Ballet review - the impressive range and reach of Christopher Wheeldon's craft

The title says it: as dancemaker, as creative magnet, the man clearly works his socks off

The Forsythe Programme, English National Ballet review - brains, beauty and bravura

Once again the veteran choreographer and maverick William Forsythe raises ENB's game

The Forsythe Programme, English National Ballet review - brains, beauty and bravura

Once again the veteran choreographer and maverick William Forsythe raises ENB's game

Add comment