Digging the Great Escape, Channel 4 | reviews, news & interviews

Digging the Great Escape, Channel 4

Digging the Great Escape, Channel 4

Archaeo-doc excavates the real story of famous POW breakout

The archaeological documentary is becoming the obligatory format for tackling legendary tales of the British at war. Someone seems to recreate the Dam Busters raid every six months, the wrecks of battleships HMS Hood and the Bismarck have been tracked down in the ocean depths, and Time Team have excavated various subterranean artefacts from the Western Front.

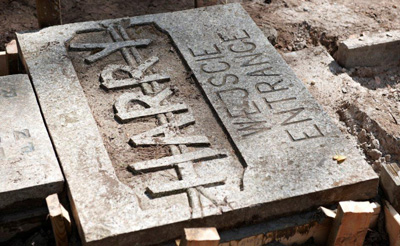

In Digging the Great Escape, we followed a team of historians, archaeologists and mining engineers to the site of the German Stalag Luft III prison camp in Silesia (now Poland), where 10,000 allied airmen were held captive during World War Two and from which 76 of them took part in what became known as the Great Escape. Specifically, our experts were searching for the famous tunnels which the prisoners dug for their getaway, nicknamed Tom, Dick and Harry by the participants. Harry was the one through which the captured flyers actually emerged into the freezing, snowy darkness on the night of 24 March, 1944. Fifty of them were subsequently executed by the Germans (plaque marking the entrance to tunnel Harry, pictured below).

Though the Hollywood movie, The Great Escape, was mostly fiction and an excuse for Steve McQueen to show off on a motorbike, plenty of factual details about life in Stalag Luft III and the tunnel-digging programme are available from a variety of published accounts. The ingenuity and persistence of the escapers and their helpers were already well known, but finding tangible proof of the way they tackled a mountain of seemingly insurmountable problems was mind-bending indeed.

Though the Hollywood movie, The Great Escape, was mostly fiction and an excuse for Steve McQueen to show off on a motorbike, plenty of factual details about life in Stalag Luft III and the tunnel-digging programme are available from a variety of published accounts. The ingenuity and persistence of the escapers and their helpers were already well known, but finding tangible proof of the way they tackled a mountain of seemingly insurmountable problems was mind-bending indeed.

The investigators initially concentrated on finding the entrance to the Harry tunnel, and thought they had when they uncovered a faint square shape in the ground in roughly the right place. They were so confident that they set about sinking an impressive new shaft a few yards away, from which they proposed to advance into Harry. However, calamity loomed when they discovered that what they'd found wasn't the Harry entrance after all. Then there was rejoicing when they belatedly found the real Harry, followed by further misery when they discovered how difficult it was to dig a tunnel in the sandy ground of Stalag Luft III. Unless the sides of the hole could be be shored up almost instantly, they just kept caving in. A series of catastrophic underground collapses forced them to give up on Harry altogether.

Still, this did prove that the escapers' efforts had been every bit as extraordinary as posterity has painted them (identity document forged by Allied prisoners, pictured left). They'd used boards taken from their bunks to fortify the tunnels, and a Canadian Spitfire pilot and ex-gold miner devised a method of locking the boards together by cutting tabs in them, so no nails were required. In order to cut the tabs they'd had to make a saw, which was done by using the steel spring from a gramophone, then cutting teeth in it with a file. One of the six RAF officers who'd joined the project to build a new tunnel in emulation of their wartime predecessors accomplished the teeth-cutting procedure in about 12 hours.

Still, this did prove that the escapers' efforts had been every bit as extraordinary as posterity has painted them (identity document forged by Allied prisoners, pictured left). They'd used boards taken from their bunks to fortify the tunnels, and a Canadian Spitfire pilot and ex-gold miner devised a method of locking the boards together by cutting tabs in them, so no nails were required. In order to cut the tabs they'd had to make a saw, which was done by using the steel spring from a gramophone, then cutting teeth in it with a file. One of the six RAF officers who'd joined the project to build a new tunnel in emulation of their wartime predecessors accomplished the teeth-cutting procedure in about 12 hours.

The loss of Harry was partly compensated for by the discovery of tunnel George, built underneath the prison camp's theatre after the great escape had taken place. Foreseeing the end of the war looming, the prisoners feared they might be lynched by vengeful German civilians, and dug George to reach underneath the camp's armoury so they could get weapons to defend themselves. George was also used to store some of the airmen's homemade devices, such as an air-pump made from kitbags, with valves cut from shoe leather to ensure the air could only flow in the required direction.

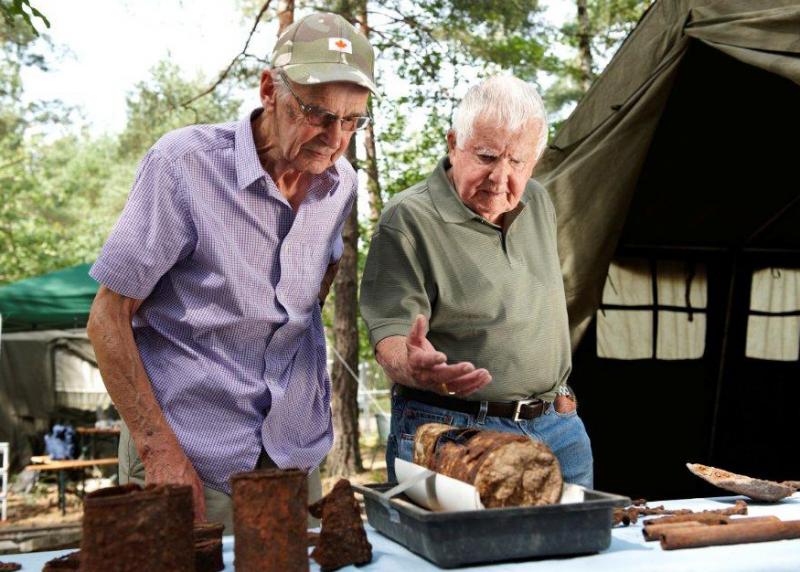

In addition there were ventilation ducts made from empty tins, elaborately forged identity cards, the remains of an electrical wiring system that hooked into the theatre's power supply, and a homemade radio inside a biscuit tin. Even the elderly camp survivors who'd been brought over to look at the excavations could hardly believe what they'd accomplished. The way modern-day Europe is heading, it might be time to brush up on some of those long-lost tunnelling skills.

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more TV

Blu-ray: The Sweeney - Series One

Influential and entertaining 1970s police drama, handsomely restored

Blu-ray: The Sweeney - Series One

Influential and entertaining 1970s police drama, handsomely restored

I Fought the Law, ITVX review - how an 800-year-old law was challenged and changed

Sheridan Smith's raw performance dominates ITV's new docudrama about injustice

I Fought the Law, ITVX review - how an 800-year-old law was challenged and changed

Sheridan Smith's raw performance dominates ITV's new docudrama about injustice

The Paper, Sky Max review - a spinoff of the US Office worth waiting 20 years for

Perfectly judged recycling of the original's key elements, with a star turn at its heart

The Paper, Sky Max review - a spinoff of the US Office worth waiting 20 years for

Perfectly judged recycling of the original's key elements, with a star turn at its heart

The Guest, BBC One review - be careful what you wish for

A terrific Eve Myles stars in addictive Welsh mystery

The Guest, BBC One review - be careful what you wish for

A terrific Eve Myles stars in addictive Welsh mystery

theartsdesk Q&A: Suranne Jones on 'Hostage', power pants and politics

The star and producer talks about taking on the role of Prime Minister, wearing high heels and living in the public eye

theartsdesk Q&A: Suranne Jones on 'Hostage', power pants and politics

The star and producer talks about taking on the role of Prime Minister, wearing high heels and living in the public eye

King & Conqueror, BBC One review - not many kicks in 1066

Turgid medieval drama leaves viewers in the dark

King & Conqueror, BBC One review - not many kicks in 1066

Turgid medieval drama leaves viewers in the dark

Hostage, Netflix review - entente not-too-cordiale

Suranne Jones and Julie Delpy cross swords in confused political drama

Hostage, Netflix review - entente not-too-cordiale

Suranne Jones and Julie Delpy cross swords in confused political drama

In Flight, Channel 4 review - drugs, thugs and Bulgarian gangsters

Katherine Kelly's flight attendant is battling a sea of troubles

In Flight, Channel 4 review - drugs, thugs and Bulgarian gangsters

Katherine Kelly's flight attendant is battling a sea of troubles

Alien: Earth, Disney+ review - was this interstellar journey really necessary?

Noah Hawley's lavish sci-fi series brings Ridley Scott's monster back home

Alien: Earth, Disney+ review - was this interstellar journey really necessary?

Noah Hawley's lavish sci-fi series brings Ridley Scott's monster back home

The Count of Monte Cristo, U&Drama review - silly telly for the silly season

Umpteenth incarnation of the Alexandre Dumas novel is no better than it should be

The Count of Monte Cristo, U&Drama review - silly telly for the silly season

Umpteenth incarnation of the Alexandre Dumas novel is no better than it should be

The Narrow Road to the Deep North, BBC One review - love, death and hell on the Burma railway

Richard Flanagan's prize-winning novel becomes a gruelling TV series

The Narrow Road to the Deep North, BBC One review - love, death and hell on the Burma railway

Richard Flanagan's prize-winning novel becomes a gruelling TV series

The Waterfront, Netflix review - fish, drugs and rock'n'roll

Kevin Williamson's Carolinas crime saga makes addictive viewing

The Waterfront, Netflix review - fish, drugs and rock'n'roll

Kevin Williamson's Carolinas crime saga makes addictive viewing

Add comment