theartsdesk Q&A: Actor Toby Jones | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk Q&A: Actor Toby Jones

theartsdesk Q&A: Actor Toby Jones

The star character actor on playing Turner, Capote and Julia Roberts' stalker

Toby Jones’s cameo in Notting Hill – he was cast as an over-eager fan of Julia Roberts - was deposited on the cutting-room floor. Most actors would have chalked it up as one of life’s bum raps. Jones, who while on set for his short scene was also failing to rent a flat in Notting Hill, fashioned a drama out of a double crisis. To perform Missing Reel he obtained permission to show the suppressed material.

Not that Jones’s run of poor luck was quite over. In Capote, Philip Seymour Hoffman had a simultaneous crack at the effete high-pitched author of In Cold Blood and won an Oscar for it. The producers decided to hold Infamous back for a year, but felt guilty enough about pressing the pause button on its star’s career to circulate rushes to generate work for him. Jones (b 1966) has never looked back.

In that year of waiting he filmed The Painted Veil and Amazing Grace and played Robert Cecil to Helen Mirren’s queen in Elizabeth I. In 2008 came three more films with Jones’s crinkly features in the mix: he played Bill Murray’s sidekick in sci-fi fable City of Embers, Karl Rove in Oliver Stone’s Dubya biopic W., while in Frost/Nixon he donned the thick-framed specs of Hollywood super-agent Swifty Lazar. No more leads, in short, but the high-profile character roles started coming in droves. He has also voiced Dobby in the Harry Potter movies, and played a sadistic figure in Ian Dury’s childhood in Sex & Drugs & Rock & Roll. Forthcoming films include The Rite, Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy and a role as the dastardly Arnim Zola in Captain America. Plus something he can’t talk about starring Robert De Niro.

The theatre performance that got Jones noticed was in The Play What I Wrote, the theatrical homage to Morecambe and Wise in which he starred with the Right Size comedy duo. The last couple of years have found Jones returning to the stage in lead roles – in Tom Stoppard’s collaboration with Andre Previn, Every Good Boy Deserves Favour at the National, Jez Butterworth's Parlour Song at the Almeida.

Watch the trailer for Parlour Song

Now in The Painter Jones plays JMW Turner. Rebecca Lenkiewicz’s play is a commission from the newly rebuilt Arcola Theatre in Dalston, north London, raised on the premises of a paint factory established in 1776 which Turner most probably visited to buy pigments. As he takes on the biggest theatrical role of his career, Toby Jones talks to theartsdesk.

JASPER REES: Let’s start with The Painter. What lured you to a new play in a small theatre in north London?

TOBY JONES: The Painter is a play about painting, but specifically about JMW Turner on the precipice of success. It’s dealing with his relationship with women, but more to do with the effect of his relationship with his mother who was mentally ill and at that time was confined first to St Luke’s and then to Bedlam. And who lived with the Turner family when he was painting in that tiny house in Covent Garden. The relationship conjures up his relationship with mental illness: where do these paintings come from? Where does genius come from?

I knew Rebecca’s writing, and then when I read it I found it incredibly moving. He’s one of those people like Shakespeare who is unavoidable. His genius is unquestioned. Those strange skies seem to be years ahead of their time. I was interested in that and in Rebecca’s take on it. Something happens in the climax of the play which moved me: his description of the act of conceiving a painting I found very, very moving. It’s interesting how inarticulate people are when they are totally articulate in another way, and interesting to find a language which explains where that comes from.

Your theatre work has increasingly involved leading roles: Parlour Song at the Almeida and before that Every Good Boy Deserves Favour (pictured right).

Your theatre work has increasingly involved leading roles: Parlour Song at the Almeida and before that Every Good Boy Deserves Favour (pictured right).

Tom Morris [the director] commissioned me to write my one-man shows at BAC; he started me off. So it was fantastic to go and work with Tom whom I had known for a long time. It was odd because it was a return to movement-based theatre which I hadn’t done for a long time. I was nervous about it. It was very physical. It’s about as physical as a Stoppard play gets. But I did love doing it and the adrenalin one gets performing in and among an orchestra is unrepeatable.

Your father is the actor Freddie Jones. Is it your perception that he’s proud of you?

I think he is in that way that a father has a tricky relationship with… As you get older and think why you’re doing anything, and what you might be aiming for and what your real motivation is under your stated motivation for doing anything at all, you wonder what the role of your father is in that dynamic. Whether you’re emulating or rejecting. I always remember that argument. Even if you’re rejecting it you’re actually acknowledging its impact on your life anyway.

You didn’t reject acting, though.

No, but I did feel very strongly that I should reject it. In that classic way of the son wanting to do something different than join the family firm. Drama school got me really interested in it. At university I went to Manchester and it was an excellent course where the first thing you do is study critical perspectives on all forms of drama, and there was an underlying feeling that theatre is under threat throughout the whole of the course. “We will be looking at theatre but remember, it’s under threat. It may not survive. It’s spawning other forms but it’s in jeopardy.” I was relieved after public school to go somewhere where they were prepared to go, “What’s the point of Shakespeare?” Not because they didn’t see a point but they were just challenging the whole idea of canon. The way they talked about drama, there were many other fields that you might want to go into. Not just film and TV but the way theatre practices have fed into every area of life: psychoanalysis, training, people viewing themselves as heroes in their own drama.

Are you the hero of your own drama?

Well, I’m very aware of trying. Having grown up with an actor I have the advantage of watching an actor’s life and how it’s very possible to succumb to the feeling of being a victim. And I’ve tried very, very forcefully to resist that temptation. In that sense, yeah, I may be the hero of my own life because I’m trying not to be the victim of it.

How could you have been a victim?

The traditional acting model of sitting by the phone and being imprisoned by the way you look and people’s perception of you and how in some way that stymies your life. Or that you can point fingers and go, “It’s because of that that I’m not there.” You can’t argue with it. If you want to view your life like that you can, because there are certain inalienable truths. You are a prisoner of the way you look. And it’s only very few actors who get to shift that in any way, shift their careers to become something other than being defined by the way you look.

When did you harness the way you look?

It’s not that simple. [Jacques] Lecoq is one of the teachers of my life. The enjoyment of that school - it was a romantic impulse to go somewhere where people clearly didn’t believe theatre was dying. He saw actors as writers rather than people who just got given writing. That actors improvise and make their own theatre. There are skills to learn and concrete ways to look at the world, and use what you see and all of the intuitive stuff that you feel as an actor, that actors who go to traditional drama schools are forced to keep to themselves. That was at the very centre of the training. There were skills you had to learn in order to implement them and create new kinds of theatre.

What age did you come out of the Lecoq school?

Twenty-two, 23, 24. I was there 1989 to 1991. I came out with a tremendous feeling of responsibility, that you are going to be responsible for your own theatre, that you’re going to have to go out and make things happen and you don’t need to get involved with the industry at all. Whether it meant going on the street, which is not what I did, or form companies and start doing shows - that’s what you were meant to do.

Your experience of being left on the cutting-room floor in Notting Hill fed into that.

We had to come up with another show – me, Edward Kemp and Jane Heather. We’d done about three shows. I was interested in making a show with a foley artist. I said I had this rather extraordinary experience where I felt I was very much at this crossroads in my life, moving house. There was a café and I was looking to rent a flat in Notting Hill which I couldn’t afford, and I was going up for auditions in films including Notting Hill, and when we came to shoot we were shooting at the same crossroads - and in fact I was sitting there waiting to go on, with Julia Roberts and Hugh Grant in the café, where I was looking for somewhere to live and on the day I was going in. And Hugh Grant was very personable and realised I was an actor, and Julia Roberts wasn’t quite clear about the distinction between my fan costume, that I might be an actor. I started talking about this whole series of coincidences and I realised there was a show there.

It’s only latterly that someone has said, "It’s like a revenge drama or something, you’re seeing conspiracies where there just aren’t any." I went, "I’m just piling on stuff which happened."

The other remarkable thing is that when I used to do it onstage, Richard Curtis gave me permission to show the footage of the scene onstage, and people would go, "So it was true?" And I’d go, "I think I’d make up a better story than that." The only reason to do it is that it’s true. It’s a rubbish story if it isn’t true. Also I was really influenced by Ken Campbell. He really is captured by imagination. When I saw Pigspell it was the kind of theatre I really wanted to make. The idea of strolling onstage and spinning plates – I just remember laughing and being so intrigued. This whole idea of theatre as disorientation, which I love, the idea that you go in and you’re properly disorientated by something - I get a lot of pleasure out of total disorientation.

Was that a metaphor for where you were as an actor?

It wasn’t even a metaphor, it was the truth. I wish I could say it was, but it wasn’t. I think I felt I’d make something creative out of something not massively disappointing. You didn’t get to play a little part in a film, it’s not the end of the world. The actor’s life, no matter how successful you are, teeters.

Back then you were being cut out of a major British film. Some years later you were the lead in a Hollywood film, Infamous. It’s an extraordinary change-around, though that’s probably not your perception.

Why isn’t it going to be my perception?

Because you’ll probably say it was a gradual rise. That’s not what it looks like from the outside.

I think it’s more chaotic. I’m guessing, but I’m sure that when you’re looking at an actor’s life it appears to have a structure.

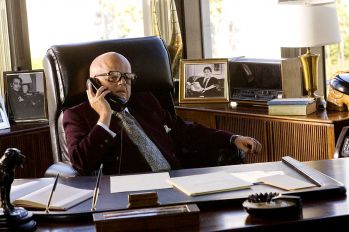

What made them think they could finance a film around you? Obviously you were surrounded by big stars (pictured left, Jones with Sandra Bullock).

What made them think they could finance a film around you? Obviously you were surrounded by big stars (pictured left, Jones with Sandra Bullock).

I think that’s key. I think Doug [McGrath] has said in interviews as soon as he saw me for the screen test - and I was only seen because a casting director had seen me in New York in The Play What I Wrote and wanted me to do a play about Truman Capote – he said, "Oh, my God, he looks a dead ringer for Truman Capote but can he act it?" Obviously they filmed it and took that away and they had a confident executive that day, that month, who just went ,"Yes, we’ll take him."

Had you had any previous awareness of a resemblance?

None whatsoever. I had no knowledge of Truman Capote. Other than being one of those rather fantastic names that we don’t get called in this country. I was aware that he appeared at Factory parties when I read about Andy Warhol. He was ubiquitous in that way.

I’m unaware of what happened in the genesis of The Play What I Wrote. Once the play was on, was it all generated by all of you?

I was friends with them because of the devised theatre world, and was a fan of theirs. They said it would be great one day to do a show. They said, "We’d really like you to do this next show, it’s about Morecambe and Wise." I was in rehearsal for Missing Reel and I remember just going, "Why on earth would you want to do a show, no matter if it’s in the West End, about Morecambe and Wise? People who like you compare you to them. It would seem to be like a poisoned chalice." They explained the basis that they were going to try and write a show about people one of whom was refusing to do that. Morecambe and Wise shows structurally are about their own fabrication. Like a lot of musical acts they’re about, "Is the act going to work?" You can play that trick with it. Then they said, "We’ve got all these little parts we’d love you to play." I said, "Please don’t say you’ve got loads of little parts. I want to play a part." They said, "Well, let’s make it a part. A guy who has to play lots of parts. He’s a stooge."

They wrote the play and sent it to me and it was funny. It was long but it was funny. Then they said, "We’ve got Kenneth Branagh to direct it." And we arrived in the rehearsal room and what was fantastic about Kenneth Branagh is he is very straight-down-the-line theatrically practical. It was one of the most inspiring things that [producer] David Pugh did as a producer was go, "That Ken Branagh really understands about making things populist."

Whereas the Right Size had come from the fringe where you get a bit more slack about meta-theatrical references, Branagh just excised all of that and said, "It’s got to be funny from moment to moment to moment." That process of trying to work out what was really going to be funny about this idea to people who go to West End theatres became very collaborative, because there were four of us in the room. It was impossible to not contribute. Also the great thing about working on a show like that is it’s changing day to day, guest by guest.

How early on were they introduced as an idea?

That was the impossible thing. David Pugh said, "I can get a guest star every night." And I went, "This isn’t going to happen, this show, is it?" It was a ludicrous proposition. But it was always fundamental. Again Pugh’s genius is that he saw that if you could do that you’d have fantastic marketing leverage.

At what point did your involvement in the whole guest phenomenon deepen?

When it became clear that I was going to have to imitate every single guest we ever had.

Was that your idea?

That was always in the play. And I think at that stage Daryl Hannah was in the West End. There was a big debate in the papers about Hollywood’s impact on the West End. Daryl Hannah became a character in the first half. I was in it playing her every night in the first half and then I had to have an appalling attempt at playing…

Who was the most difficult?

Who was the most difficult?

It’s a terrible barometer of people stardom. When they came on there were three broad categories. I’d be busy imitating somebody. The guest star comes on stage right. Fantastic theatrical frisson goes through the audience. "Jesus Christ, it’s them!" Sometimes there’d be utter silence for about 30 seconds which was the moment for people to go, "That really is Roger Moore" (pictured taking a bow with the cast). The second level is "Oh, they’ve got them, how good, we knew they were getting a guest star, they’ve got that one." The third one was where we’d have to set up more and more within the material what they’d actually done.

Did they understand their celebrity was being measured?

Yes, I think they must have done.

If you were a celebrity in it, which category would you be in?

That’s a challenge I would always reject. Listen, the third. I’m in no way a celebrity whatsoever. I don’t view myself in any way. What really worked in that format was when it became clear, a bit like Morecambe and Wise, they were straight actors with some authority who’d shown up for a show that they clearly shouldn’t have taken and were having the piss taken out of them. Absolutely ideal guest: Ralph Fiennes. The roof came off that night because he literally looked in the wrong place. I think I’d roughly look in the right sort of place: yeah, he needs the piss taken out of him!

Did anyone react rather badly to the whole thing?

Yes. In America everyone volunteered. They saw the show and prepared. Holly Hunter was brilliant at it. She was one of the greatest people we could have met. I remember her describing to us how she prepared, reading The Piano when she got the script and what she then did to get the part. It was amazing to hear her level of engagement with the material.

What did you do with Capote?

I never really stopped working. I read everything I could read. That’s all slightly adjacent, all that stuff. They key thing was trying to work out why the fuck would someone end up with a voice like that. In Cold Blood is an incredible book. I couldn’t believe I hadn’t read it. What I understood the argument of the film to be was that he never wrote anything nearly as powerful and he never wrote anything before or after like it. So it must have come from some experience. Which is why I think it became the locus of two films.

Watch the trailer for Infamous

How did you cope with the fact of the other film, which had more heat under it?

We always knew it was there. I then had far too much to think about because of the kind of actors I was going to work with to ever even think about the other film. Daniel [Craig] had auditioned for the other film so he told us the script. We went, "That sounds incredibly similar." He went, "Yeah, it is quite similar." No one seemed very worried about that. What was really hard was the hiatus before the release, the decision to hold it back for a year. Luckily I got a lot of very good jobs in that period that distracted me from it, on the basis, I might add, of incredible generosity from the producers who sent out rushes of Infamous to other directors and said, "You should see this guy."

The Painted Veil, Elizabeth, Amazing Grace (pictured below, Jones in Amazing Grace).

That was really hard. But I never thought for one second I would ever be a lead part. Everyone tells you that anything can happen when you‘re an actor. You wouldn’t become an actor if you didn’t have that dream. But then you also know the chances of being the lead actor in an American film are very, very, very small. And I was very aware that I was fucking lucky the film was even going to be released. In fact, if the other film had died our film probably wouldn’t have been released.

That was really hard. But I never thought for one second I would ever be a lead part. Everyone tells you that anything can happen when you‘re an actor. You wouldn’t become an actor if you didn’t have that dream. But then you also know the chances of being the lead actor in an American film are very, very, very small. And I was very aware that I was fucking lucky the film was even going to be released. In fact, if the other film had died our film probably wouldn’t have been released.

Have you met Hoffman?

Never met him.

Seen the film?

No, still haven’t seen it. Just haven’t. There's no kind of like "I’ll never see that".

What is a character actor?

I’ve no idea what a character actor is. Not now either, because even more so I think most of the films you want to be in have actors who are called character actors in the lead roles. The most interesting films. George Clooney in a way often positions himself as a character and he clearly isn’t a character actor. Hoffman. They’re technically not handsome. They’re technically characterful which is a euphemism for asymmetrical features. I’m just showing you that I’ve got asymmetrical features.

You certainly have if you hold your hand diagonally across your face like that.

I tell you what I really think it is. I never thought I’d get the chance or the time that Daniel Day-Lewis had to totally transform yourself. As an actor there is a fantasy somewhere that you will be able to become someone else. When you read about actors being kept out of city walls in the 17th and 18th century you think it’s probably because they were really good liars and really good at telling you things exist that don’t. I’m romantic about that, in the sense that I feel, wouldn’t that be great? Maybe that’s what I got into with Ken Campbell. It was never quite clear what had happened to him but you wanted it to have happened as he said, but you weren’t quite sure.

Was there a moment as a young actor when you realised you weren’t going to be the juve lead?

Not a moment. Just through watching my father’s career and the kind of roles that he got offered. I was also aware of the chance element. That’s also to do with how as an actor you’re using your real-life experiences, about where you sit in groups of people. Where do you position yourself? Are you someone who can lead a group of people at times or are you someone that refrains from doing that? How do people tell you that they see you in a group of people? To a certain extent that’s what acting teachers are telling you. They’re going, "You seem to be this kind of person. If you want to be that kind of person you probably need to start thinking about these things." But I think I was pretty aware of that growing up. A self-consciousness about where you sit with your peers or older kids or younger kids. Like all of us are. You hope that there is a director out there who says you can play anything. The parts you get excited about are the ones where you go, I never thought I’d…

I got cast as this soldier. My agent said, "Oliver Stone wants to cast for this Vietnam film," and the script came through and I was reading it going, "This is like the Vietnam films I watched, there doesn’t seem to be any part in here for me - a British diplomat or a gay writer. There’s nothing." I rang the agent and said, "Are you sure he wants to meet me for that part?" "Yeah, definitely." "I don’t want to go in there and make a fool of myself." I walk in and literally there are all the guys who should be there and Oliver Stone goes, "Listen, man, whatever you want to play in this, we’d love you to be in it." He’s seen Infamous and said, "I really love that film." I remember just going, "Yeah, you like the film so what the fuck?"

What did you really say?

I said, "Thank you very, very much."

What happened?

I went out to rehearse for two weeks with Bruce Willis to play his colleague researching the My Lai massacre.

So you weren’t up for a soldier?

That was just a compliment. He meant the part that I came in for, which was a soldier investigating with Bruce Willis what happened at the My Lai massacre. It was shelved because Bruce Willis pulled out of it.

Then Stone cast you in W. Did you have a sense of what Karl Rove looks like?

I like to think I look better-looking than Karl Rove (pictured right, Jones as Rove). He was, I think, probably in the Top Three most-hated people in the States. Certainly after Cheney, possibly after Bush. The famous book written about him is called The Brains Behind Bush, because he’s the self-confessed nerd on metrics, this thing of studying political swing and where votes may be gained. He has an incredible memory for these figures and is a workaholic. He’s revolutionary in the fact that he changed in a cynical but very effective way the way that people should lead campaigns, that they should attack the opposition not on their weaknesses but on their strengths. He basically refined Bush’s message down to four key things: gay marriage, wartime leader, whatever else they were. So that whatever question Bush was asked he’d always answer on these four issues.

I like to think I look better-looking than Karl Rove (pictured right, Jones as Rove). He was, I think, probably in the Top Three most-hated people in the States. Certainly after Cheney, possibly after Bush. The famous book written about him is called The Brains Behind Bush, because he’s the self-confessed nerd on metrics, this thing of studying political swing and where votes may be gained. He has an incredible memory for these figures and is a workaholic. He’s revolutionary in the fact that he changed in a cynical but very effective way the way that people should lead campaigns, that they should attack the opposition not on their weaknesses but on their strengths. He basically refined Bush’s message down to four key things: gay marriage, wartime leader, whatever else they were. So that whatever question Bush was asked he’d always answer on these four issues.

How did you play him?

You try and get footage of him, you try to hear how he sounds, you read the script again and again and again and see what his function in the drama is. And then how different he is from myself? That’s effectively what you’re doing. How different is this guy from me? I need to address myself to the things that are different. There’s the voice, the way he moves. It’s very hard to find because you normally get to see him from only here upwards. And also he goes through a time change. You see him right at the beginning when Bush is running for governor. You do whatever you can.

Listen to Toby Jones discussing his role as Karl Rove in W.

Actually I found him possibly the hardest character that I’ve ever had to work on because he seems to have more of a twinkle in his eye when people are slagging him off, there’s this laughter in his eye like that kid in the playground. He doesn’t seem to give anything away. And there’s no literature about what he has for breakfast. It’s not out there. and in fact he’s known for his very invisibility. Whenever anything bad happened to the Democrats or a Republican candidate that the Republicans wanted to ditch they’d talk about the hand of Rove. The hand of Rove basically meant you couldn’t detect Rove’s participation in what must have been his plan.

How about Swifty Lazar (pictured, Jones as Swifty Lazar in Frost/Nixon)?

How about Swifty Lazar (pictured, Jones as Swifty Lazar in Frost/Nixon)?

Again quite hard to find out much about him. A Hollywood legend. I listened to him dictating his showbiz memories and that was fascinating. Like Truman, a very short guy but flamboyant. You sense a meanness somewhere. It goes with the territory of haggling for years over more and more money. I don’t know what to say other than a bit like Truman but more so - he’s someone who doesn’t see himself as absurd but who looks patently absurd, going, "I’m a macho guy, I totally belong in this world," a showbiz agent mixing with President Nixon and all of these high-flying political people.

I felt there was an odd blind spot seeing his own incongruity: that I shouldn’t at any point suggest that I was a freak or eccentric even though I look like a freak and pretty eccentric. When I listened to his voice it was clear that this guy was raised in the Russian part of Brooklyn, a music agent, really tough guy going out for jazz bands in the gangster back streets and doing deals. He’s a tough guy without being a tough guy. He’s not physically tough but he’s fucking tough. I’ve spoken to people who’ve known him and they’d go, "Swifty was really… quite a character." They wouldn’t ever say, "What a great guy, funny guy." I don’t think he was any of those things. I think he was a tough fucker.

Does success in film make it hard to come back to theatre?

The only plan is that rather boring actor’s answer which is to do the best script that comes through.

Do you ever hanker for it?

I don’t hanker after being in week seven of a nine-month run. Just to be in the theatre for month after month after month. There comes a point sometimes… you become an adrenalin junkie. It’s very hard after a long run of a play to get that adrenalin.

Does a character actor ever get to kiss the girl?

In The Painted Veil I got to go away with a supermodel. James Bond, I got to kiss him. I had a whole year of being asked what it was like to kiss Daniel Craig.

Watch Truman Capote kiss James Bond (as it were):

Did Infamous make you more recognised on the street?

That was a surreal thing. To sit next to someone who’s making the decision whether to watch your film. I was literally sitting next to someone on a plane. And they did. There was bit of BlackBerry going on during the film. A bit of scrolling. But then the engagement with the film. Then the meal comes, eats meal watching film. And then because it’s such a unique thing to happen I literally tried to get his attention, because I thought, this is just too weird, he hasn’t noticed. I remember going, "Could you pass me something?" that didn’t need passing. He went, "Yup, sure." I went, "Did you enjoy the film?" "Sorry?" "Did you enjoy…?" And he went, "Jesus Christ almighty!" But it took him a little moment. And this is after surgery, remember.

Do you give thanks for your face?

No, I don’t give thanks. I don’t view it like that. I don’t think about it very much.

What was your response to being asked to play Dobby (pictured right)?

What was your response to being asked to play Dobby (pictured right)?

Inappropriately financial. I had no knowledge of the books or anything. I didn’t have kids at the time. When I told people who did have kids they went, “Fantastic.”

You’ve got other films coming: Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy, The Rite, Captain America. Do you have a sense of where you are, in terms of status or clout?

I don’t really know where I am. It’s quite hard to know. You guys decide where we are. I try to keep myself interested for as long as possible in a job where it’s very easy to get stuck in a rut. That’s the thing, to try and stay as engaged as one can. It’s easy to say but for everything you do there are difficult decisions about jobs that you don’t do. I never thought I would be in that position, to be honest. The next thing I’m doing after this is a film with Robert De Niro, and I can’t quite believe I’ll be acting with Robert De Niro but everyone tells me that that’s what I’ll be doing. You wouldn’t dare to say, “Oh, it’s going really, really well, I think I’ve cracked it.”

Explore topics

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Comments

...