Bingo, Young Vic Theatre | reviews, news & interviews

Bingo, Young Vic Theatre

Bingo, Young Vic Theatre

Edward Bond's play about a tired, rich Shakespeare who spends his money unkindly

Bingo: Scenes of Money and Death is the misleading, jokey title of a play about Shakespeare in his ignoble last years, unable to write further, isolated from his beloved London, and hemmed in by local politics. Shakespeare is invited to become a town councillor! To take sides in a dispute about land enclosures! It’s a cracking re-visioning of the genius whom films and myth have preserved in the aspic of lusty, piratic eloquence.

In Edward Bond's creation of 1974, Shakespeare is a middle-class capitalist literary squire, who sits in his big Stratford garden, rich, lionised and 52 (old, in those days), hasn’t written anything for five years since The Tempest, has a moaning wife he can’t abide, a nagging daughter, an oversexed old gardener, a brash landowner neighbour, and a fear that without his words he’s dying. He is asked to get involved in other people's desperate lives - a vagrant woman living off prostitution begs for help, an angry young man urges the peasants to resist enclosures - but Shakespeare signs up with the landowners to buy himself peace and quiet.

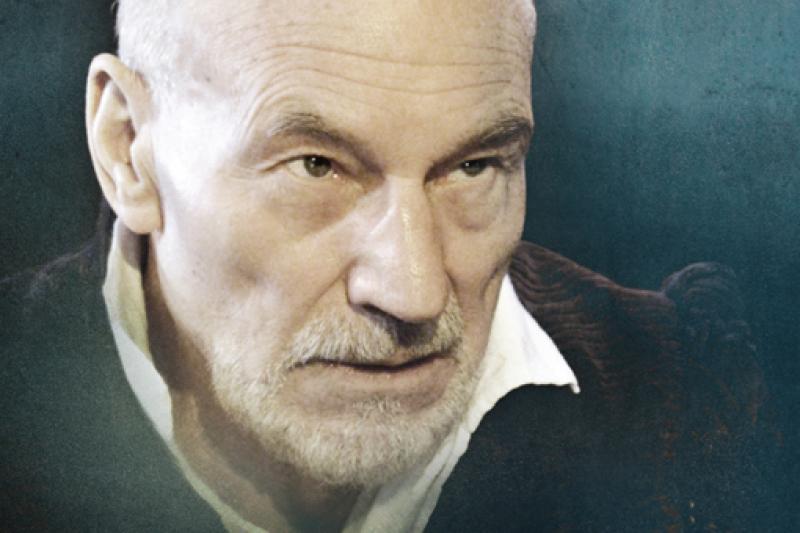

Bond was 40 when he wrote the play, and perhaps that’s why the attacks he sets up upon his Shakespeare feel like that of a son vigorously trying to land a telling blow on his father. It almost works, because in Sir Patrick Stewart’s performance you can so easily believe in the life portrayed. Writer’s burn-out is both risible and tragic - cocky Bond wants to suggest that moral burn-out was a relevant factor. In the fleetest and best scene, a jealous Ben Jonson (charismatic Richard McCabe in enormous, swelling breeches) beards Shakespeare in a Stratford pub, getting him drunk, taunting him with his air of superiority over other playwrights, with sitting in his rich man’s garden while the Globe burns down, with losing his touch. “You’ve been writing some peculiar stuff lately - what was The Winter’s Tale about?” he jeers. Stewart just sits and stares at him through narrowed eyes, saying nothing, and draining another goblet. (Stewart and McCabe, pictured right)

Bond was 40 when he wrote the play, and perhaps that’s why the attacks he sets up upon his Shakespeare feel like that of a son vigorously trying to land a telling blow on his father. It almost works, because in Sir Patrick Stewart’s performance you can so easily believe in the life portrayed. Writer’s burn-out is both risible and tragic - cocky Bond wants to suggest that moral burn-out was a relevant factor. In the fleetest and best scene, a jealous Ben Jonson (charismatic Richard McCabe in enormous, swelling breeches) beards Shakespeare in a Stratford pub, getting him drunk, taunting him with his air of superiority over other playwrights, with sitting in his rich man’s garden while the Globe burns down, with losing his touch. “You’ve been writing some peculiar stuff lately - what was The Winter’s Tale about?” he jeers. Stewart just sits and stares at him through narrowed eyes, saying nothing, and draining another goblet. (Stewart and McCabe, pictured right)

It's a damn good set-up, not nice but plausible - still I’m not sure that this really adds up to a play about characters who change, rather than a tiptilted hommage. The simple-minded gardener (struck accidentally by an axe in someone else’s fight - a ghoulishly funny idea) has shades of Poor Tom about him as Shakespeare has shades of Lear. The stand-off between the religious-zealot son and Matthew Marsh’s excellently smug landowner, Combe, is a black-and-white affair.

Bond guns the social issues, but stumbles over the necessary language to make these ancillary characters sparkle - they prate, they strike attitudes (proto-feminism, proto-socialism), they’re even boring. He boldly gives Shakespeare monologues, musing on his distraction and sickness, or berating his daughter Judith with his hatred for her pettiness, or recalling the horror of walking into the Globe via an arch of 16 severed heads, but the speeches are much more interesting for what they say than how they say it, the language refusing to fly.

The playing is rich, thoroughly understood by Stewart, by Ellie Haddington’s housekeeper, John McEnery's gardener (the two pictured left) and Catherine Cusack’s much-put-upon Judith, in particular. They all performed this in its Chichester Festival Theatre origination in 2010. But do I believe in it? There’s the rub. Bond’s Shakespeare is passive, self-serving and not very poetic. While Stewart is marvellous at listening - sometimes he’s blocking the noise out, sometimes he’s absorbing it - that no-nonsense set of the mouth does radiate a natural forcefulness that contradicts any impression of self-absorption (or “serenity”, mocks Ben Jonson).

The playing is rich, thoroughly understood by Stewart, by Ellie Haddington’s housekeeper, John McEnery's gardener (the two pictured left) and Catherine Cusack’s much-put-upon Judith, in particular. They all performed this in its Chichester Festival Theatre origination in 2010. But do I believe in it? There’s the rub. Bond’s Shakespeare is passive, self-serving and not very poetic. While Stewart is marvellous at listening - sometimes he’s blocking the noise out, sometimes he’s absorbing it - that no-nonsense set of the mouth does radiate a natural forcefulness that contradicts any impression of self-absorption (or “serenity”, mocks Ben Jonson).

This may be because the ensemble, under Angus Jackson’s direction, plays it fast and light. There are scenes of jet-black comedy - Shakespeare in his sickroom refuses to let his screaming wife and daughter in, pushing his will under the door to them while his housekeeper doesn’t know whether to laugh or cry. And Judith’s impotent revenge, ignoring her father’s death-throes to rifle hysterically through his papers for a more obliging will, makes a biting punchline to this dysfunctional family tragedy.

The notion of a Shakespeare spoiled and emasculated by adulation and power is a good one - in a sense that’s Lear too. But Shakespeare’s Lear is devastatingly moving while Bond’s Shakespeare is not. I'd put it down to the language: Bond's got the plot and the character, but not the songs, the poetry. I don't hear an original lyrical power of Bond's own there, so he doesn't make it matter to me that this Shakespeare has fallen silent.

Patrick Stewart with Ricky Gervais on Extras

rating

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Theatre

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: Refuse / Terry's / Sugar

A Ukrainian bin man, an unseen used car dealer and every daddy's dream twink in three contrasting Fringe shows

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: Refuse / Terry's / Sugar

A Ukrainian bin man, an unseen used car dealer and every daddy's dream twink in three contrasting Fringe shows

Faustus in Africa!, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - deeply flawed

Bringing the Faust legend to comment on colonialism produces bewildering results

Faustus in Africa!, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - deeply flawed

Bringing the Faust legend to comment on colonialism produces bewildering results

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: Imprints / Courier

A slippery show about memory and a rug-pulling Deliveroo comedy in the latest from the Edinburgh Fringe

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: Imprints / Courier

A slippery show about memory and a rug-pulling Deliveroo comedy in the latest from the Edinburgh Fringe

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: The Ode Islands / Delusions and Grandeur / Shame Show

Experimental digital performance art, classical insights and gay shame in three strong Fringe shows

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: The Ode Islands / Delusions and Grandeur / Shame Show

Experimental digital performance art, classical insights and gay shame in three strong Fringe shows

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: Ordinary Decent Criminal / Insiders

Two dramas on prison life offer contrasting perspectives but a similar sense of compassion

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: Ordinary Decent Criminal / Insiders

Two dramas on prison life offer contrasting perspectives but a similar sense of compassion

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: Kinder / Shunga Alert / Clean Your Plate!

From drag to Japanese erotica via a French cookery show, three of the Fringe's more unusual offerings

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: Kinder / Shunga Alert / Clean Your Plate!

From drag to Japanese erotica via a French cookery show, three of the Fringe's more unusual offerings

The Two Gentlemen of Verona, RSC, Stratford review - not quite the intended gateway drug to Shakespeare

Shakespeare trying out lots of ideas that were to bear fruit in the future

The Two Gentlemen of Verona, RSC, Stratford review - not quite the intended gateway drug to Shakespeare

Shakespeare trying out lots of ideas that were to bear fruit in the future

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: The Horse of Jenin / Nowhere

Two powerful shows consider the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, with mixed results

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: The Horse of Jenin / Nowhere

Two powerful shows consider the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, with mixed results

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: The Fit Prince / Undersigned

A joyful gay romance and an intimate one-to-one encounter in two strong Fringe shows

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: The Fit Prince / Undersigned

A joyful gay romance and an intimate one-to-one encounter in two strong Fringe shows

Tom at the Farm, Edinburgh Fringe 2025 review - desire and disgust

A visually stunning stage re-adaptation of a recent gay classic plunges the audience into blood and earth

Tom at the Farm, Edinburgh Fringe 2025 review - desire and disgust

A visually stunning stage re-adaptation of a recent gay classic plunges the audience into blood and earth

Works and Days, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - jaw-dropping theatrical ambition

Nothing less than the history of human civilisation is the theme of FC Bergman's visually stunning show

Works and Days, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - jaw-dropping theatrical ambition

Nothing less than the history of human civilisation is the theme of FC Bergman's visually stunning show

Every Brilliant Thing, @sohoplace review - return of the comedy about suicide that lifts the spirits

Lenny Henry is the ideal ringmaster for this exercise in audience participation

Every Brilliant Thing, @sohoplace review - return of the comedy about suicide that lifts the spirits

Lenny Henry is the ideal ringmaster for this exercise in audience participation

Add comment