Misery and comedy have always been happy bedfellows. The sad clown, the stand-up who falls down offstage – we know who we’re talking about. But for all their problems, comedians don’t generally make a habit of turning medical pathology into material. Until now. Ruby Wax has crafted an entire show out of her depression. Anyone who has seen her glorious documentary interviews with Pamela Anderson and Imelda Marcos, to name a couple, might have guessed she is manic. But a depressive?

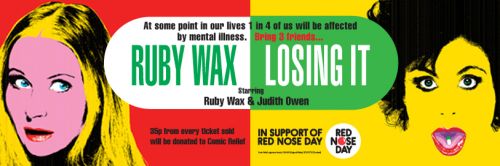

Wax (b 1953) was diagnosed while pregnant with her third and youngest child. She went into the Priory and has been back three times, including for one long stay of six weeks. Losing It, the show she built around her experiences, toured the UK last year and now comes to the Menier Chocolate Factory. But it was first tried out at all dozen branches of the Priory, playing to audiences containing not just fellow sufferers from mental illness and their families but also, bizarrely, hen nights. Directed by Thea Sharrock, the show is actually a two-hander incorporating music by Judith Owen, the singer-songwriter who has also suffered dramatically from depression.

The show is rather more than a guide to mental illness. Delivered in her trademark style, mixing the outspoken diatribe and a comic parade of insecurity, the Wax weltanschauung includes some very funny material on the vacuity of the celebrity lifestyle. There is also an element of the confessional as she owns up to monstrous behaviour in the past. The argument of Losing It is that, more than anyone, the mentally ill flail through life without a manual. Wax nowadays has more access to the manual than most, having trained as a psychotherapist. It involved hundreds of hours of not only receiving psychotherapy but giving it, which must have been a surreal experience for any clients who were also fans of Ruby Wax Meets... When theartsdesk meets Ruby Wax, it is apparent that she talks about these weighty matters in a way that is fraught with a new and intriguing complexity.

"You'll know when you've got it": Ruby Wax on depression

JASPER REES: Why did you want to perform live at the Priory?

RUBY WAX: I don’t think you could get a better audience. If depressives laugh you know you’ve got a hit. It’s a good way of checking it. And also I always got on with people that have problems. We talk the same language. Put me into any alcoholic smoky room, though I’m not an alcoholic, and I’m pretty much the popular girl there. But with mental issues I’m really popular. We were speaking to our people.

What was the point in the course of your illness at which you thought, I could do a show?

It isn’t about mental illness.

But it’s not your average stand-up.

Oh, it’s not. I don’t know how to do stand-up. For 10 years I had been in front of the computer trying to write serious comedy, to develop a style. It’s usually a very young media because you’re all pepped up with your own hormones and excitement of having all that attention. It’s on pure adrenalin and they don’t notice that they’re not talking about anything, but their rhythm is so catchy. And then they get old and they realise they’re talking about the funny thing their cat did or they memorise bits of history or whatever and throw that in, but really there’s no point to it. And you have to either retire, like Dawn and Jennifer did, because they did really young characters, brilliantly, or you end up like Tommy Cooper, insane, doing "The Golliwog Song". I thought I was on drugs when I watched him. Or they die of a heart attack because they can’t match their work with their maturity. So I thought I gotta do some age-appropriate comedy. But I don’t mean sappy like Robin Williams showing you a picture of his daughter when she was born. I mean smart, but very funny and everybody of every age would get it. But that took 10 years to figure out. I just kept throwing the paper out. Once it was set in the Priory I got it.

At what point did you realise you had your subject? When you were in the Priory you presumably were not thinking of comedy.

I wasn’t thinking.

So at what point did you think, this is material?

Never. Even when we put it on at the Priory. First of all I raised everything to do with the Priory and depression so that nobody would be put off. Also I’m not doing the mental-head version of The Vagina Monologues to a select few. So it was only the bracket of it, and then I could talk about everything in the world. Now I have physics in it in a very bizarre way. You could talk about the brain, you could talk about relationships and the absurdity of caring about anything and being lost with no manual within the bracket of "we’re all in the Priory, one way or the other". So it wasn’t like I got to take the piss out of this building. Once I had where it was I could carry on but I never was going to say anything about the Priory. But when people watched it the first time they said, "Why don’t you say what goes on in there?" So at the end I start to talk about the class where we had to be chickens and then find the other chickens – I can’t make up stuff – I only put that in at the last minute. It was not to say what went on in there.

The Priory were all OK with this?

They wanted to break the stigma. You can’t do better than this. They’re right behind it.

When did you become aware that mental illness was a problem for you?

I can’t tell because I thought I had different things like glandular fever, and then labyrinthitis. I’d have this thing where I’d go into a waking coma.

What period in your life?

Twenties. When I was at the RSC. I’d have to check into a hotel. Everybody thought it was really bizarre but nobody knew what it was. Then when I was pregnant with [her third child] they said, "You better get some help." I met someone who said, "You really do have clinical depression," and I was really happy because I had a name. So then she came out and then they put me into the Priory shortly after.

So that was your first time in the Priory. In the show it seems it wasn’t a long or useful visit.

It was only useful because I met the most extraordinary people. There was a woman withdrawing from drugs and she was in a Chanel outfit the whole time. She was a lawyer and a doctor and a concert pianist. And the conversations were remarkable. That feeling that they can be like me but be so bright actually made it better. Then it lifts and you don’t know why.

Why did you leave after only a few days?

When you’re resilient you can get out fast. And they give you drugs. And then if time goes on and you have three episodes it starts to get deeper and longer. So if I have another one I need the insurance to stay even longer. Unless this time it’s the end. It might be. You never know. I might have paid my dues. I went a couple of times in between but they were just short stays too.

When was the first one?

It was 15, 16 years ago.

The most recent one you talk about as a longer and darker event. How long was it?

Six weeks.

You’ve not tended to talk about this over the years.

No, it’s really embarrassing. I thought I would be fired from my job. I always lied and said, "I don’t have that. I have other things." It’s really embarrassing because why should a person as lucky as me be so self-indulgent as to have something wrong when there are people in the world that have nothing? But then gradually it gets out that it’s an illness that anybody can get. It doesn’t really point the finger at a special class.

It has been de-stigmatised somewhat in recent years. What did you make of Stephen Fry’s documentary on the subject?

I thought it was irresponsible. Because if you are bipolar you really should be on drugs. And again if I go, "Yeah, we can get through it," well, we can’t. Some people end up hanging from a noose. He said he doesn’t take his medication.

Have you taken issue with him?

No, it’s not my business but I just don’t think it’s a great message. Again, we’re saying, "Yes, we can get through it, especially if we have a career." Well, you can’t.

How much is the show about mental illness?

We’re not talking about mental illness. You don’t work 10 years to get up and say, "I’d like to talk to you about mental illness today." I happen to be mentally ill. It only comes out in the last three pages. But I don’t say, "I’m not going to tell you about it and wank on." I mention at the beginning, "Something’s wrong with her - I’m fine." And then literally in the last three pages you start to see it catching up with me. But then actually I pull out by the end. Which is true. I am OK. I went back to school and learnt how my brain works. And I’m continuing to go to school. I have been going to school for six years.

Studying what?

Neuroscience and psychotherapy. Which I started off studying at Berkeley but I got confused and ended up being an actress.

For Judith Owen (pictured right with Wax) it was music that was her balm. What was it for you?

For Judith Owen (pictured right with Wax) it was music that was her balm. What was it for you?

Medication.

How about doing this show?

I like doing it. But I never think of the audience. They say they really like it, but they might be lying.

I don’t know whether you’re joking.

I’m not joking. But I have a good time.

At what point did illness interfere with your career?

It never did because I would time it such. Once I had it when I was doing a daytime show and I had to quickly check myself out. You could see it on my face. But the audience really can’t tell. I don’t know what I’m talking about then but you can’t tell. I’ve had it on TV but I’m so scared that my job is on the line that I just keep going.

Those interview documentaries you did in the late Nineties – was it not professionally and personally fulfilling to produce such excellent work?

Yeah, that was fulfilling but then I demand that of me. And then I see all the loopholes when I’m editing it. I see the flaws.

But they were brilliant shows.

I don’t believe you. If I believe you for a minute I get my ass kicked by karma and I’ll be run over by a truck this afternoon. Because it happens every time. Every time I get a minuscule twinge of I think I did something good, every time something comes and kicks me in the ass.

But don’t most comedians have that?

Oh no, I think McIntyre feels pretty good. What’s that guy, Michael McIntyre? Some comedians feel very good.

You talk very funnily about your upbringing in the show. Is there any part of you that is grateful to your parents for giving you this thing that you can talk about?

I’m grateful that they were so smart. She was mathematically brilliant. And I didn't get the math but now studying neuroscience I think if I hadn’t had such a bad background I would really have been interested. But I missed it when I was young because I was so distracted. I couldn't read a book. I was trying to survive.

Your childhood was evidently an extremely quirky one. Could you have been the entertainer you are now without that upbringing?

They say that and then I worked with Jennifer Saunders who likes to muck out and head flowers and is probably the most normal person that I know and has genius that I’ll never even contemplate.

So background doesn’t explain anything?

I don’t think so. How would we ever know?

"Where's the manual?": Ruby Wax live at the Edinburgh Festival

Are talent and illness in any way indivisible or would you actually have the same range of talents without the illness?

I was interviewing an autistic kid and I said, "What’s the benefit?" and he said, "I’m a really good artist." I said, "Well, there’s a trade-off." Of course it isn’t because he suffers. It’s like me asking the autistic kid, "Would you still be able to draw?" I don't know. There is no answer. And science doesn’t know either. So how would I know? I wish I was an academic.

You talk in the show about realising at a certain point that the trappings of success and fame were turning you into a kind of a monster.

A narcissist.

When did you notice that happening?

I don’t know. It was very gradual. I can’t tell how I felt getting it but I can tell the withdrawal. It’s so gradual when you’re in it. Sometimes you don't notice because it’s like you took a drug but it doesn’t feel like anything. It’s just a high.

Celebrity brings status and privilege. When did you realise, as you admit in the show, that you were behaving badly?

I’ve only heard rumours. I’m never aware of how I act. People said I’d pick a victim. But again, I don’t know if I would do that anyway. I would pick somebody weaker than me and pummel them. But that might be in my personality anyway, which has now gone because I’ve done so much work. Or I would be so demanding that nobody would argue with me. But it was always about making my shows perfect. It was never about a limo. It was the demand of being in that edit room all night until it was perfect and if somebody tried to fuddle with it I would murder them. Every edit was my edit. I think people have gone down because they changed my edit. That was the insanity: the perfection. I never had the other one of wanting clothes or anything. I don’t like any of that. It’s always an irritation when you have to dress up.

In your show you talk about keeping a cab waiting a long time.

That’s part of my illness. I like to wait until it’s honking and then I get dressed really quickly so I can get an adrenalin hit. That’s not to do with fame. Once I got on a flight from America with no passport. Then I knew I had arrived. I lost my passport. A gay man happened to be on immigration in England and said, "Let her in." And then the Americans said, "Who is this person coming through the military line?" They said, "If you can make all three of us laugh, we’ll let you in?" And then Virgin put me in first class. I never pay first class. And so that’s fame. I would only pay economy.

Is the Priory the best audience this show is going to get? You’re preaching to the converted.

No, because about three times a week I’m paid a lot of money to go to big events and I use the material and they don't even know I do a show and they really laugh, so I guess funny is funny. Though again when I talk about Pamela or why we gloat when there’s a tragedy, everybody finds that funny.

How large does your Pamela Anderson interview loom in the collective memory?

I get letters. Everybody asks me. Airplane pilots, milkmen, taxi drivers going, "’ey, Roob, what are them jugs like? What are them Bristol Creams like, Roob?" And they really do. And I get letters from South America. "¿Che esto Pamela Anderson bazookas por favor?" And I think I’m an artist so that really bugs me. But she did make me famous. Though I had done 10 years of great documentaries before that, they didn’t make me famous. But they were the best work I ever did. And sadly I’m not remembered for those. People will always go, "What was Madonna like?" And my face falls to the floor. Anybody could have interviewed Madonna.

Ruby Wax meets Pamela Anderson

You say in the show repeatedly, like a refrain, "Why does nobody tell you there’s no manual?" Why does nobody tell you?

Because there is no manual. There just isn’t. There is another show to be written after this one ends about what goes on in the mothership and that is the manual. "Sorry, you’re not that important, but it really knows how to run you." It being you. So there’s a real interesting area now about how the brain runs and the division between that and the mind.

What is your ultimate aim or ambition with your studying?

I like teaching. I do it with companies. I talk a lot about how the brain works, which is the new zeitgeist, and if you understand how it functions you have more of a chance of self-regulating. It’s not a big mystery: I am the way I am. You can actually tune in now and start to lower your cortisol. It is an orchestra and the frontal cortex is the conductor and that’s how they’re going to start working with therapy in 10 years and sadly I’ll be too old. This is really the cutting edge. That’s what I want to be doing. The more I can control my cortisol the better I communicate and the better my life will be.

Do you still do therapy?

No, I don't believe in the talking cure.

Did you do it?

I studied it for a long time. I mean I finished it. I did my so many hours of it. I had a lot of clients. And it’s a relationship that heals. It’s down to the relationship whatever method you use. It’s 90 per cent the person feeling that you’re listening. Everybody knows that. You can study as long as you want.

Why and when did you stop psychotherapy?

When I got into neuroscience. Then I thought, whoa, we’re stepping up a few paces here. Psychotherapy is a good metaphor. It’s a good bit of guesswork that Freud did there, considering that he wanted to be a neuroscientist and he couldn’t get into a live head. But he guessed well.

Is there a lesson in the show?

I say it in a few lines at the end of the show that as you age and you’re not fearful of it and don't bore people senseless with the past and if you stay open and flexible and curious, then you get wisdom. Now that should be everybody’s goal who’s lost their looks.

Have you got wisdom?

Some. I’ve got a little bit. But I’ve got a few years. More than psychotherapy gave me. That’s insight into yourself. Wisdom is starting to get other people.

How did it feel going back to the Priory to perform?

So comforting. They let me sleep there, because I love the smell of the nursery and the nannies, the big mummies coming in and speaking in their gentle voice. I really would give up everything if I could live there. And it’s hot and then the smoking room is so much fun.

Is the appeal that you have no responsibility?

Being hospitalised is my idea of a good time. It feels like home.

- Ruby Wax: Losing It at the Menier Chocolate Factory from 15 February to 19 March. From every ticket sold 35p will go to Comic Relief

Find Ruby Wax on Amazon

Find Ruby Wax on Amazon Find Judith Owen on Amazon

Find Judith Owen on Amazon

Ruby Wax and Judith Owen talk about mental illness onstage

Add comment