Q&A Special: Choreographer Javier de Frutos | reviews, news & interviews

Q&A Special: Choreographer Javier de Frutos

Q&A Special: Choreographer Javier de Frutos

Dancemaker hopes his ballet with the Pet Shop Boys won't result in death threats, for once

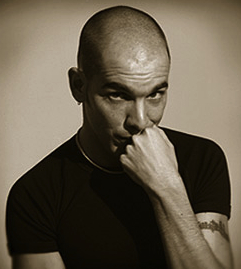

Born in Venezuela 48 years ago, de Frutos has never been the fairytale type, at least not overtly. His 20-year career of choreography has been a career of unstoppable fecundity, violent flamboyance, extreme, even grotesque exhibition, outrageous passion. To many he’s a shock jock of contemporary dance.

I thought Eternal Damnation to Sancho and Sanchez a grotesquely funny satire from the stable of Chris Morris, South Park and Richard Thomas - “as jawdroppingly yeurghy as the Circus of Horrors, and has been calculated to a tee to provoke walkouts and boos from the audience,” I wrote in my review. De Frutos had warned in advance that he was contriving a scandalous final course to an evening of otherwise graceful and decorous ballets.

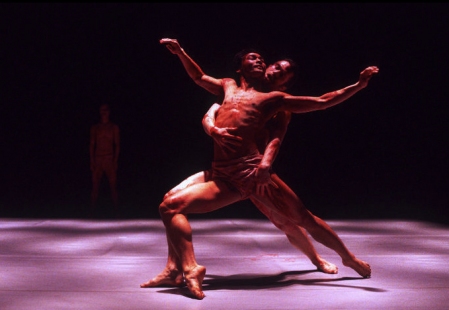

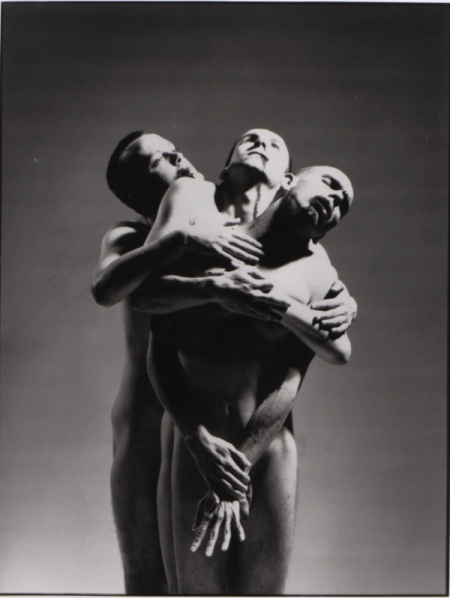

But I have seen more horrific and upsetting work from him, in Los Picadores, a bloodbath of choreographed violence that left me deadened with pessimism (Los Picadores, pictured left by Chris Nash), and in a masterwork I doubt I’ll ever forget, the claustrophobic, bloody and mentally suffocating sexual trio Grass.

But I have seen more horrific and upsetting work from him, in Los Picadores, a bloodbath of choreographed violence that left me deadened with pessimism (Los Picadores, pictured left by Chris Nash), and in a masterwork I doubt I’ll ever forget, the claustrophobic, bloody and mentally suffocating sexual trio Grass.

Naked is what de Frutos does, physically and emotionally. When I first saw him in his twenties dancing nude to Bartok’s massive Sonata for Two Pianos and Percussion, his lithe little body and bobbling penis were elfin, defiant on the huge waters of the music. He had already created a nude solo for himself to part of Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring, music he’s choreographed four times, most recently a headspinningly romantic ensemble for the Royal New Zealand Ballet, Milagros.

The wounded outsider is de Frutos territory - he’s a very bright, lippy Latin, exorcising his Spanish Catholic upbringing on stage in a torrent of dance pieces that don’t even attempt to conceal that he’s gay, he’s angry, this is what being him is like, and it’s always about being found different, about feeling cut out, bereft. Woe betide anybody who thinks he’ll sit silently and suffer what he believes to be an injustice.

The wounded outsider is de Frutos territory - he’s a very bright, lippy Latin, exorcising his Spanish Catholic upbringing on stage in a torrent of dance pieces that don’t even attempt to conceal that he’s gay, he’s angry, this is what being him is like, and it’s always about being found different, about feeling cut out, bereft. Woe betide anybody who thinks he’ll sit silently and suffer what he believes to be an injustice.

When a collaborative film by him and Isaac Julien was nominated for the 2001 Turner Prize, the ownership dispute ended up in court. The South Bank Show gave him the prestigious film treatment in 2000, as he prepared what I thought was the one wholly narcissistic piece of his I’d seen, The Hypochondriac Bird, an hour-long detailed enactment of two men having sex. When my review appeared in the Daily Telegraph, Javier left a 20-minute monologue of misery and fury on my answerphone. It was lacerating to listen to it, but then I’d felt flayed. After a night out with Javier's picture-show, you tend to come home begging for comfort.

A fairytale certainly seems an unlikely area for his sometimes poxed imagination, and when we met last Thursday I wasn’t disappointed to hear that he has taken an off-centre line with Hans Christian Andersen’s tale. But I think everyone will be extremely surprised to hear how he’s handling the “happy ever after” ending. It’s really quite as much a shock as anything else he’s done. Read theartsdesk's review of the show.

With the happy-ever-after in fairytales you never know what happened after breakfast the next day

ISMENE BROWN: What are you doing in these last few days up to the premiere?

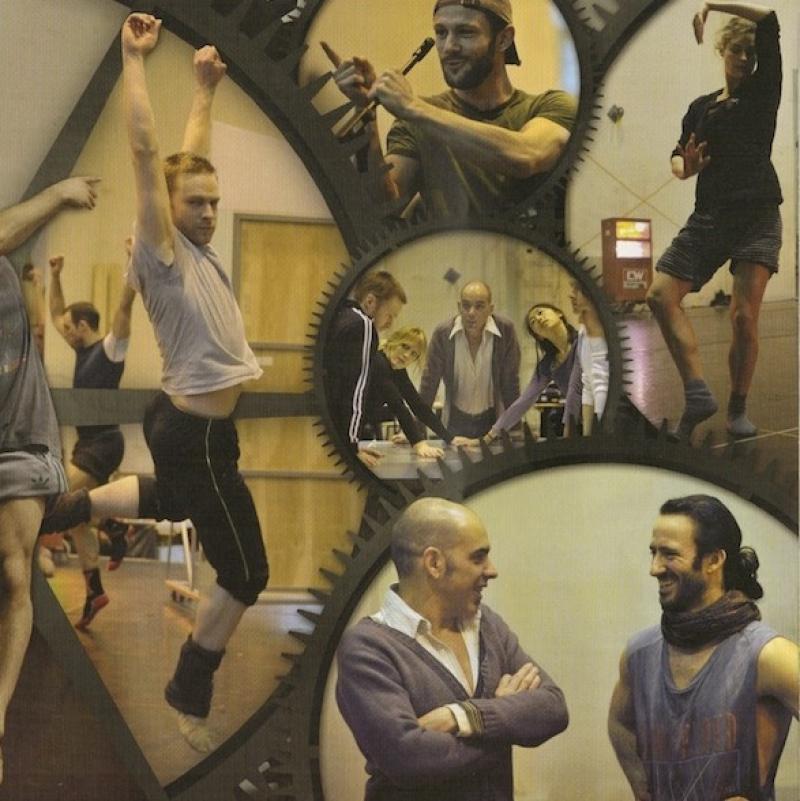

JAVIER DE FRUTOS: It’s all about last-minute multimedia and tech checks. I thought I’d bite the bullet on multimedia but it’s very hard to get right - it takes a long time. Also I need this last bit of time to take a step back and direct the show, edit it.

Multimedia and digital is everywhere in dance now, but it’s harder to use than hard scenery, isn’t it?

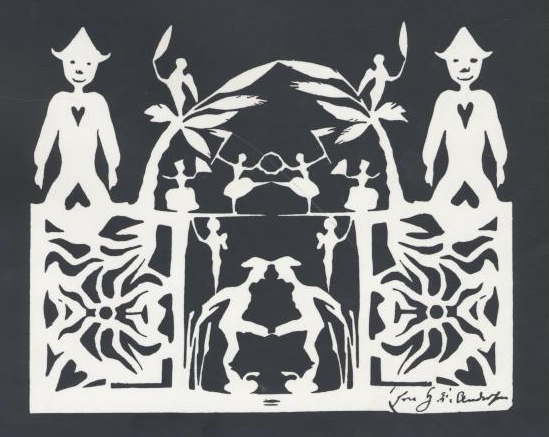

Yes, it definitely takes much longer. I didn’t want to use what appears to be the mega-latest technology because every time you think you’re ahead in IT you’re behind. But I knew it would be important in telling the story - there’d be characters who had to appear briefly, like the judges who appear on a live satellite link from somewhere. I wanted it with slightly rough edges, like as if the Eurovision Song Contest had been set up in Minsk in the Soviet Union in 1969 or something. It means you still have to use the latest technology for it to work! But if we played it again in 10 years' time it needs to work as a picture (below, a Hans Christian Andersen paper cutting).

The King announces a competition: the person who invents the most incredible thing will win half his kingdom and the hand of his daughter. The story is that this geek, this mouse of a man, invents the most incredible thing, a clock on whose every chime a new figure appears. That suppressed country has never seen anything like it, so he clearly wins. But the jealous man - who is played by Ivan Putrov, the ex-Royal Ballet dancer - doesn’t have that power of creation and turns the dare into destroying the clock. And so destroying the most incredible thing must itself be the most incredible thing, since nothing remains of the previous one. By the rules the King has no choice but to hand his daughter to this destroyer.

But during the “black” wedding, as we call it, the power of creation reassembles the parts of the clock in a new form and they destroy the bad guy. By that time, as Neil [Tennant] said very cleverly, the essence seems to be that you can destroy the object but you can’t kill an idea. But then Anderson takes it a bit further, which is to say that the final happiness of art having the last say - of reversing the facts of destruction - causes no jealousy at all. After the princess and the inventor get together, despite the destruction of the incredible thing he created, in the end the most incredible thing is that not one person resented it. So I interpret it that the most incredible thing is what to you is most incredible, being human.

Then I took that on a bit further, because with the happy-ever-after in fairytales you never know what happened after breakfast the next day. So we finish with a little tailpiece 50 years later. They’re still married - the most incredible thing! It’s that contentment has won. I think the older we get, the more our understanding of what is incredible keeps changing.

The girl has no say in anything in the story?

Absolutely. This has been very interesting with intelligent dancers, that they ask the right questions. A: where is the mother? So there are parental issues here. B: Why is the King giving away half the kingdom? Is this a troubled country? Is the girl pretty much being given as a slave, as a price here? And she is very young, a teenager, oppressed, with hormones raging.

And thirdly you have a dictatorship.

And thirdly you have a dictatorship.

Yes, so that clearly steered the look of its world. We knew it needed to be an artistically interesting world - we’re not doing a Harold Pinter drama - and because of the Boys’ influence too we would go to an era of Russian constructivism. The story itself was partly inspired by the Franco-Prussian war, and in World War 2 it was used by Danish resistance as a cautionary tale. So there are already political implications. But you have to be careful with those, as at the heart of the story there is a girl who wants to grow up and have a say in her life.

Even when we were designing the look of it, I kept saying, let’s go back to basics. What was the thing you’ve seen that took your breath away? Both Katrina [Lindsay, the production designer] and I said Olafur Eliasson’s sun in the Tate Modern. I knew it was only smoke and mirrors, but the effect was most incredible, an extraordinary act of creation that makes any artist jealous.

Who had the idea of using this story?

Ivan [Putrov] had asked the Boys to create a ballet for him. He’s becoming a real modern dancer. It’s been heartening to see his chemistry with Clemmie [Sveaas], it’s palpable.

Ivan has a very classical background and image and his participation in this seemed almost the most incredible part of this. Was his ballet background inspiring for you choreographically?

The most inspiring thing is seeing him come out of his shell - he’s playing the villain, of course, the destroyer. I am very physical with my guys, and they’ve known for a long time about that - we have no censorship. Sometimes I have to ask them to do things that are completely OTT so I’m the joker here with the megaphone, but it’s also necessary for them to see that while we don’t take ourselves too seriously we take the job very seriously. I wanted Ivan to be able to take this on so that muscle-wise he’d be malleable. Aaron [Sillis], who is completely the opposite, has a great relationship with him now, and Ivan is really part of the company now. You know how my villains are! My villains are villains…

Chris and Neil had a sketch of about 20 minutes of music that they were working on - I think it was a ballet to begin with, then it’s now become an album (pictured right). We had almost a two-year creative process while the story was changing, because they needed a model of what would be on stage so as to know what music to write.

Chris and Neil had a sketch of about 20 minutes of music that they were working on - I think it was a ballet to begin with, then it’s now become an album (pictured right). We had almost a two-year creative process while the story was changing, because they needed a model of what would be on stage so as to know what music to write.

How do you find the music? You do like big music - you’ve done Tosca, Madame Butterfly, Rite of Spring, Les Noces...!

I like it. It is really big music - there are passages in it that are enormous. I’m having palpitations about the fact that usually the composers I use are dead so they can’t tell me off, but here I’m like a kid constantly searching for the approval of these composers when they come in to watch. I like the idea that we created it together and I can still say it’s been very collaborative. There have been a lot of ideas that came entirely from them, and other segments where I asked them to provide more music on specific themes. It’s been very agreeable and easy.

Someone told me not to go on stage to take a bow, because the house was going to go mental. But I said, this is a bloody panto...

I imagine it’s quite restorative - tell me about your last piece, Eternal Damnation to Sancho and Sanchez, and the aftermath.

Whe-hey!! Um. (sighs and gulps). I didn’t expect it. I think… I had a great sense of disappointment. You expect a couple of people to make a hue and cry. But it was funny - couldn’t people see it was funny? It wasn’t The Pope. None of it was “real”, and the whole exercise was done in the context of a homage to Diaghilev, who when he got together with Cocteau they planned, let’s see what they could do to piss people off. It wasn’t me being asked to “do a Diaghilev”, it was “in the spirit of…” Already the title indicated what this was. (Michael Camp as Pope Roberto I, pictured below, photo Hugo Glendinning/SWT)

It wounded you badly, the reaction.

It wounded you badly, the reaction.

It always does. People say your skin gets thicker as you get older - it doesn’t, it gets thinner. Because you get closer to the work. I really believed in it. The dancers were so extraordinarily committed. Somebody told me in the wings at the end of the first night, I recommend you don’t to go on stage to take a bow, because the house is going to go mental. And when I saw Michael Camp who was playing the Pope was actually being booed in character, I said, "But this is a bloody panto, this is not like La Scala when people boo the director, this is beyond that, this is turning into something else." I felt I almost had to become a human shield, and the conductor too, who had just given an extraordinary rendition with the orchestra of La Valse.

It took me by surprise. I was disappointed by audiences who have seen pretty much everything of me that they could see could take a step back, and I was sorry for that. Obviously there was really great support for it as well, but the reaction did become more and more extreme, and by the time the BBC turned round and said, we’re not going to show it - without explanation - yes, it was just horrific. People kept telling me, you will be the person they remember. But no, you won’t be the person they remember if you don’t work again.

You thought people wouldn’t commission you again?

They didn’t for a year. I thought I was going to lose this one too - very, very strongly I felt that. I had started working on this already, it was mine at the time, thought not signed. So I did feel I was going to be sacked any time. I do have a very good relationship with Alastair [Spalding, Sadler's Wells artistic director], I know him from when he worked at the QEH when he commissioned a lot of my work, and knows a lot of my work, and I assume he knows exactly what I do. I do work on commission very clearly.

It’s something a lot of people didn’t understand. I didn’t just suddenly put that work on stage - arrive the day before saying, "Guys, I had a great idea." The storyboard, scenario, set had been made six months before, it was sitting in Alastair’s office for six months, so those penises were already there for months. It was all planned. And because of the nature of the event I thought I would work in the spirit of Cocteau which was to create the scenario first.

So it’s all known well in advance. No one could be surprised.

Yes, of course. And you go to the BBC and say, "Christmas Day, guys? Really? You thought about this? We’re not doing Nutcracker." It was miscommunication of some kind. All my studios were open. Many people came and saw. There was never a sense of, guys, we’re going to be in trouble.

I did that TV commercial for T-Mobile. And in the middle of it I had another little breakdown, thinking, how did I get here? I’ve lost even my identity

It gave you a breakdown, the reception.

Yes. I got into a crying fit for three days, couldn’t walk out of the house. And the first two death threats arrived by post, and the third was on my mobile. And then I completely lost it. I mean, three death threats is nothing compared to what some people get, but I didn’t understand where these coming from. They were saying if the programme was broadcast, I would die.

And the BBC said, not only do we not want to present it, but we cannot protect you. We can’t put you somewhere safe. I said, oh, have we regressed so much that a half-hour ballet causes something like this? It’s hardly Martin Luther King doing a speech. This is a ballet you can switch on or switch off… I still don’t understand it to this day

Do you live alone?

Do you live alone?

Yes. I had split up with my partner the year before, I was very much alone, and I suppose I was like a leper. People didn’t come and see me, I stopped trusting people. I’m technically bankrupt now, I ending up losing my house last year. I have work for the coming year, thank goodness. I did a bit of theatre last year, Macbeth at the Globe, and I did that TV commercial for T-Mobile. And in the middle of it I had another little breakdown, thinking, how did I get here? I’ve lost even my identity. (Grass, 1997, pictured right by Chris Nash)

Do you read all the critics?

Of course! I don’t believe anybody who says they don’t.

I was interviewing Michael Clark who told me the critics were some of the very few people who might give close attention to what he was doing and give him back an engaged reaction, good or bad, to what he’d worked on for a long time. It must be great to have audience approval but how do you measure reaction?

You can’t. I don’t really foresee bringing Eternal Damnation back, though maybe somebody in future might, when the trouble has settled - but right now the only thing that people will know about that work is what they read. And with the banning of the piece by the BBC that was the one factor picked up in all the headlines. By the time it was picked up by AP and the news started travelling, I saw something in Peru, I think, which made out I’d been fornicating dogs and eunuchs, or something, it was escalating in this incredible Chinese whispers. And later on I met a director of Danza Contemporanea de Cuba who said, "Ah, you’re Javier de Frutos who killed the Pope - in Havana we’re very proud of you." I said, "I didn’t kill anybody!" But by that time it was no longer funny, I couldn’t see any humour in this. Normally I’m very self-deprecating, but I could find nothing funny about a breakdown, or about crying, or death threats, or losing my cool.

Well, it’s a sign of how strongly people engaged and were disturbed by what you did.

Well, on paper I understand everything! I’ve always been a very good guy for understanding on paper, but in reality… When I walk into the studio, I know instinctively what to do. There is that feeling of trepidation as you walk up to the door, but when you’re inside suddenly you feel what to do. Now, I don’t even know how to pay my gas bill on the internet, but I have always known what to do in the studio. So when that safe haven is invaded… I do think I’ve always created work with the audience in mind. I always want to do a show I feel I could watch myself, which is probably why I’ve always wanted big music for it too.

With this new piece the danger is you’ll make it too sweet and bland to appease people, when rage against the cage has always been your thing.

Hmm. I don’t think there’s a cage here. But you’ve already hit the nail on the head, that reading this fairy tale you’re already asking who is this girl? Why are we celebrating an act of destruction? But when Carl comes to be destroyed at the end, now he becomes part of the destruction process and parts of him are incorporated like a canvas… Maybe it’s like Guernica, or Caravaggio, a lot of religious art.

So it’s also about your own longing for happy-ever-after, for 50 years of lobotomised placidity on the telly couch with a partner…

Oh, I said to my best friend the other day I would kill to have a lap to fall asleep in while watching TV.

But looking back over your work you’ve had a 20-year career now, and it’s remarkable how much you’ve done, a piece or more a year. and bumpy ride or not, it’s been quite a brilliant career really.

Yeah, maybe. I think I have been very stubborn. Because I’m not British I always feel I have to prove my right to be here. Especially when I started getting money from the Arts Council I had to prove why I really deserve that money. I did think a few times of leaving Britain, but for some strange reason I felt I had more affinity with Britain. But I sometimes wonder what I’d have done if I’d done my career in Paris, when you see Jerome Bel being commissioned to do something by the Paris Opera Ballet…

When I think of your stand-out works… it’s hard to cut down, because all of them are highly individual. Obviously Grass, and also I remember being amazed by the courage of Meeting J, your nude solo to Bartok, and Milagros in another way… (Milagros pictured above, photo Javier de Frutos)

All of them I enjoyed doing, for all kinds of different reasons, and maybe that great commitment shows.

There’s a great connection between your emotional and intelligent instincts and what you put on stage, which is risky as it’s so full-on, but I’d like to ask about dance language itself, as you’re starting from nothing every time. You don’t start from a known vocabulary, like ballet. In this particular one where are you starting from?

We needed to create the vocabulary for people to speak and then I let them free a bit. There is a lot of it. I needed also to create a bridge between Ivan and everybody else so he believably belonged to this world, so it wasn’t the ex-Royal Ballet star and the barefoot corps at the back. I thought it was essential that Clemmie was centre of the piece.

Can children come to this?

Yes.

So it is a fairytale?

Yes, but I keep thinking of Tim Burton. Children have changed a lot. Parents have changed a lot. Families are different now, the evolution into gay families - Elton holding his baby on the cover of Hello! - the very interesting meeting of minds that is going on now in all kinds of different family structures.

This is huge, your first three-acter.

Yes. But there is always something unachieved. Before we were doing this my friend Phil Wilmott, the director, wanted to be the first person to stage Double Falsehood and his heart was so much in the right place. He asked me to design - because I have a design background too - so it was literally £20 a costume, and painting and sewing and hands-on, and I was absolutely delighted doing it. At 1 o’clock in the morning repainting the floor, and Lucy Carter, who’s doing my lighting here, said - because we had so much light to create in the show - she says to me, "You remember when we met at The Place, you were with Jamie, and we did everything with just a square of light?" And we did quite a lot with that square of light… It felt to me that you need to remember that as you move into another scale. I don’t know how I feel about dance now. If there is a story to tell, I need to tell it.

Tennessee was asked what was the future of poetry on stage. And he said, ‘Dance.’ Somewhere along the way we became preoccupied with shapes and forms, and pelvises and legs. In a very old-fashioned way I’d like to grab that concept back

What are your future outlets if you do less dance?

I keep waiting for a knock at the door asking me to direct Camino Real… That’s the ultimate I’d like to do. But literally the day after this ends I’m starting at the National, London Road with Rufus Norris again - the fourth collaboration with him - which I’m delighted about, to go into the Cottesloe. I needed to do it, like people do an indie film after a blockbuster. Royal New Zealand Ballet are doing Banderillero again when they come over to London this summer. And for Rambert in November I’m doing a piece based on the spirit of Tennessee Williams, the original Alex North score for the film A Streetcar Named Desire, a 35-minute piece. I have to work with Pieter Symonds before she stops!

Despite the awfulness of last year, you do maintain an upbeat demeanour. Maybe that corner got turned?

I think I’ll find that out this week!

Javier de Frutos timeline

- 1963 Born in Caracas, Venezuela. Trained in Venezuela, then at London Contemporary Dance School and at Merce Cunningham School, New York.

- 1988-92 Member of Laura Dean Dancers, New York

- 1991 Consecration (Rite of Spring) - New York - a half-hour solo

- 1994 Returned to London, established the Javier de Frutos Dance Company. Created The Palace Does Not Forgive (to Stravinsky's Rite of Spring), Docklands, London - solo naked under gold dress “exploring sexual identity”

- 1995 Meeting J - nude solo to Bartok Sonata for Two Pianos & Percussion (The Place)

- 1996 E muoio disperato, for Ricochet dance, set to the finale of Puccini’s ‘Tosca

- 1997 All Visitors Bring Happiness, Some by Coming, Some by Going, for Ricochet, a claustrophobic prison drama using Stravinsky’s Les Noces (Edinburgh, QEH etc)

- 1997 Grass, set to Puccini’s Madam Butterfly - de Frutos’s breakthrough work, a laceratingly painful trio about sexual possession (The Place, revived 1998)

- 1998 The Fortune Biscuit set to Stravinsky's The Soldier’s Tale, for Rotterdam Dance Group.

- 1998 The Hypochondriac Bird, a narcissistic, highly sexualised solo take on Swan Lake. Its creation is the core of a 1999 South Bank Show film on him

- 2000 The Celebrated Soubrette for Rambert, about the private lives of showgirls - and I Hastened Through My Death Scene to Catch Your Last Act for Candoco, the disabled dance group (one of their best commissions, with an exotically amusing strangeness)

- 2000 De Frutos wins an Arts Council fellowship for two years to study Tennessee Williams, whose plays inspire his own work for several years.

- 2001 Bitter dispute with collaborator Isaac Julien over the Turner Prize-nominated film they made together, The Long Road to Mazatlan. De Frutos took a financial settlement to remove his name from the piece.

- 2001 The Misty Frontier, for the Royal Ballet Artists Development Programme - a Tennessee Williams theme

- 2003 Milagros (Rite of Spring pianoroll version) for the Royal New Zealand Ballet - toured London 2004

- 2003 Elsa Canasta, for Rambert - using Cole Porter’s music for a strikingly cool, blatant depiction of a nightclub

- 2006 Nopalitos for Phoenix Dance; appointed Artistic Director at Phoenix, creates the Mexican-inspired Nopalitos

- 2006 choreographs Carousel for Chichester Festival Theatre and West End; choreographs Cabaret for the West End (wins the Olivier Award for best theatre choreographer)

- 2007 Los Picadores and Pasiello for Phoenix - one is a violently gory punch-up to Les Noces, the other an unexpectedly light-hearted and humorous Mozart work

- 2007 Kismet for English National Opera - initial choreographer, but walks out of production in dispute with director

- 2007 Venice Biennale: Phoenix performs de Frutos triple bill

- 2008 Cattle Call for Phoenix Dance, a typically scabrous and funny backstage musical with Richard Thomas

- 2008 Quits as Phoenix director, with acrimony all round

- 2009 Movement director on Death and the King's Horseman at the National Theatre

- 2009 Eternal Damnation for Sancho and Sanchez, Sadler’s Wells ‘In the Spirt of Diaghilev’ programme - banned by BBC from its intended broadcast of the entire bill

- 2010 Movement director on Macbeth at Shakespeare’s Globe

- 2010 Choreographer on T-Mobile's Heathrow commercial

- 2011 Designer on Double Falsehood, Union Theatre, London

Watch Neil Tennant and Chris Lowe discuss their ballet with Javier de Frutos

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Dance

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

R:Evolution, English National Ballet, Sadler's Wells review - a vibrant survey of ballet in four acts

ENB set the bar high with this mixed bill, but they meet its challenges thrillingly

R:Evolution, English National Ballet, Sadler's Wells review - a vibrant survey of ballet in four acts

ENB set the bar high with this mixed bill, but they meet its challenges thrillingly

Like Water for Chocolate, Royal Ballet review - splendid dancing and sets, but there's too much plot

Christopher Wheeldon's version looks great but is too muddling to connect with fully

Like Water for Chocolate, Royal Ballet review - splendid dancing and sets, but there's too much plot

Christopher Wheeldon's version looks great but is too muddling to connect with fully

iD-Reloaded, Cirque Éloize, Marlowe Theatre, Canterbury review - attitude, energy and invention

A riotous blend of urban dance music, hip hop and contemporary circus

iD-Reloaded, Cirque Éloize, Marlowe Theatre, Canterbury review - attitude, energy and invention

A riotous blend of urban dance music, hip hop and contemporary circus

How to be a Dancer in 72,000 Easy Lessons, Teaċ Daṁsa review - a riveting account of a life in dance

Michael Keegan-Dolan's unique hybrid of physical theatre and comic monologue

How to be a Dancer in 72,000 Easy Lessons, Teaċ Daṁsa review - a riveting account of a life in dance

Michael Keegan-Dolan's unique hybrid of physical theatre and comic monologue

A Single Man, Linbury Theatre review - an anatomy of melancholy, with breaks in the clouds

Ed Watson and Jonathan Goddard are extraordinary in Jonathan Watkins' dance theatre adaptation of Isherwood's novel

A Single Man, Linbury Theatre review - an anatomy of melancholy, with breaks in the clouds

Ed Watson and Jonathan Goddard are extraordinary in Jonathan Watkins' dance theatre adaptation of Isherwood's novel

Peaky Blinders: The Redemption of Thomas Shelby, Rambert, Sadler's Wells review - exciting dancing, if you can see it

Six TV series reduced to 100 minutes' dance time doesn't quite compute

Peaky Blinders: The Redemption of Thomas Shelby, Rambert, Sadler's Wells review - exciting dancing, if you can see it

Six TV series reduced to 100 minutes' dance time doesn't quite compute

Giselle, National Ballet of Japan review - return of a classic, refreshed and impeccably danced

First visit by Miyako Yoshida's company leaves you wanting more

Giselle, National Ballet of Japan review - return of a classic, refreshed and impeccably danced

First visit by Miyako Yoshida's company leaves you wanting more

Quadrophenia, Sadler's Wells review - missed opportunity to give new stage life to a Who classic

The brilliant cast need a tighter score and a stronger narrative

Quadrophenia, Sadler's Wells review - missed opportunity to give new stage life to a Who classic

The brilliant cast need a tighter score and a stronger narrative

The Midnight Bell, Sadler's Wells review - a first reprise for one of Matthew Bourne's most compelling shows to date

The after-hours lives of the sad and lonely are drawn with compassion, originality and skill

The Midnight Bell, Sadler's Wells review - a first reprise for one of Matthew Bourne's most compelling shows to date

The after-hours lives of the sad and lonely are drawn with compassion, originality and skill

Ballet to Broadway: Wheeldon Works, Royal Ballet review - the impressive range and reach of Christopher Wheeldon's craft

The title says it: as dancemaker, as creative magnet, the man clearly works his socks off

Ballet to Broadway: Wheeldon Works, Royal Ballet review - the impressive range and reach of Christopher Wheeldon's craft

The title says it: as dancemaker, as creative magnet, the man clearly works his socks off

The Forsythe Programme, English National Ballet review - brains, beauty and bravura

Once again the veteran choreographer and maverick William Forsythe raises ENB's game

The Forsythe Programme, English National Ballet review - brains, beauty and bravura

Once again the veteran choreographer and maverick William Forsythe raises ENB's game

Add comment