Cave of Forgotten Dreams | reviews, news & interviews

Cave of Forgotten Dreams

Cave of Forgotten Dreams

Werner Herzog trains a 3D camera on miraculous palaeolithic cave paintings

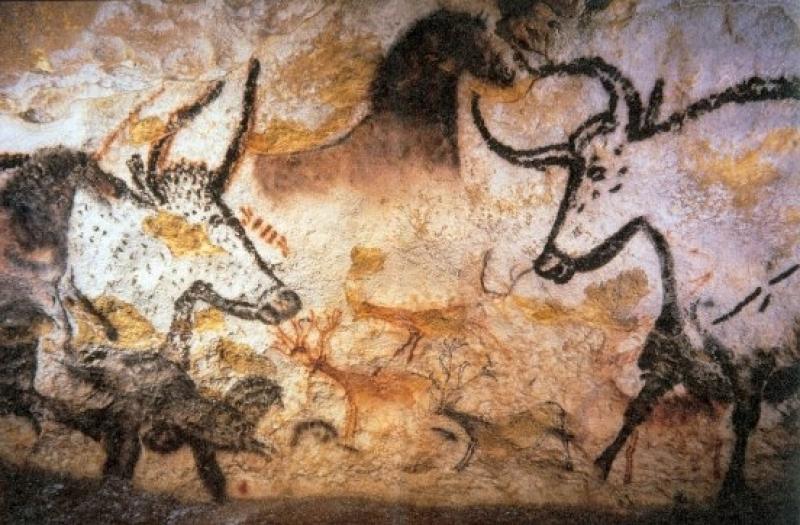

The first thing that must be said is the paintings, captured by Herzog and his crew, are breathtaking beyond description. Among the animals depicted with remarkable clarity are mammoths, horses, bison, rhinoceros, ibex, lions and the only known instance of a panther in paleolithic art. There is even a giant creepy crawly clambering up one wall. And the cave itself is a mini-miracle of preserved evidence.

Herzog has never been a film-maker to swim downstream, but his decision to go with the flow and use the latest 3D technology is inspired. Often deployed as a lazy afterthought in more sensationalist ventures, here Herzog’s camera scopes the sinuous curves and tumescent lumps of the cave walls, or creeps across its calcified floor, like a bomb-detection device, sensitive to contour, alive to the nuances of space.

Cave of Forgotten Dreams feels like a companion piece to Encounters at the End of the World, his visit to Antarctica from which he brought back astonishing images of marine life filmed in a hidden world under the sea ice. Here, as there, we get Herzog inserting himself on voiceover duties. He makes for a deadpan messenger, apparently (though you’re never quite sure) deaf to his own absurdity. His speculations as he obsessively hunts for meaning, for connection, lead him up some blind alleyways which, frankly, this film could do without – never more than in a bathetic coda which takes him to a nearby botanic garden where albino crocodiles swim in pools. (Don't ask. You are urged to leave before this bit, so that your last memory is, fittingly, of a human handprint from 30 millennia ago.)

But as it’s Herzog bringing us this story, we must learn to live with these interventions. Sometimes the cave seems to be fighting back. At one point he asks everyone, scientists and crew, to keep quiet so we can listen out for the echo of long-dead heartbeats. The camera pans across from Herzog looking sagacious to a tall stalagmite, apparently giving one of the great poets of modern cinema a one-fingered salute.

Herzog’s career in documentary bleeds seamlessly into his interest in the freaks, visionaries and weirdos who skitter and howl across the screen in Fitzcarraldo, The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser and Nosferatu the Vampyre. Here he works hard to unearth a quirky romanticism among the scientists who spend as much time as is allowed in the cave. A young archaeologist, he is delighted to discover, used to work in the circus. “Lion-tamer?” Herzog asks hopefully. Turns out he was just a bog-standard unicyclist. He also meets up with a master perfumer, an archetypal Herzogian eccentric who hunts for hidden cave openings by smell. Others give rein to their own sensory imagination: one of the cave’s curators claims to be able to hear the thud of clashing rhino horns or the gallop of hooves under a horse herd.

Another tic of Herzog is a form of solipsism - to find in the cave paintings a conjunction with the art form to which he has devoted his life. Thus the bison with eight legs suggesting movement is “like frames in an animated film”. The shadows cast by humans on the wall – now with low-heat lights (pictured above), but once upon a time with fire – evokes for him a memory of Fred Astaire dancing with huge silhouetted projections. One analogy he misses is with the glistening bulbous accretions growing on the cave floor, which resemble nothing so much as special effects from Ridley Scott’s Alien.

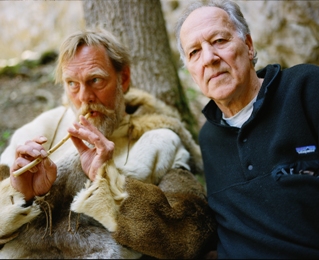

There isn’t quite enough material from the Chauvet cave to fill a whole film, so Herzog diverts to Swabia in south-west Germany where evidence has been found of contemporaneous human life, including a pentatonic flute on which a fur-clad expert (pictured right with Herzog) plays “The Star-Spangled Banner”. There is also a demonstration of hunting weaponry (“I will try to show you how to kill a horse,” says a bearded expert, goofily). The 3D camera catches the wooden spear with flint blade jabbing threateningly through the screen.

There isn’t quite enough material from the Chauvet cave to fill a whole film, so Herzog diverts to Swabia in south-west Germany where evidence has been found of contemporaneous human life, including a pentatonic flute on which a fur-clad expert (pictured right with Herzog) plays “The Star-Spangled Banner”. There is also a demonstration of hunting weaponry (“I will try to show you how to kill a horse,” says a bearded expert, goofily). The 3D camera catches the wooden spear with flint blade jabbing threateningly through the screen.

You could more or less set your watch by the moment Herzog gets round to mentioning Picasso, who was stimulated by other paleolithic finds. You’d love to know what Leonardo, that obsessive student of anatomy and kinetic motion, would have made of it all – of the eyes of lions shining with intense vivacity, or a white horse with a coal-black head, or one bison whose mighty heft all but barges its way off the wall.

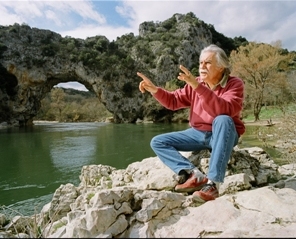

The question arises of who these artists were. Herzog ponders all sorts of ideas about their spirituality, about the (to him) mystical Wagnerian landscape of the Ardèche gorge which features a river curling through a rocky arch (pictured right with French scientist). The title of the film itself feels like no more than a whimsical bit of Freudian editorialising. Were these products really the product of dreams? In the end, nobody knows anything other than what is supplied by the evidence. The archaeologists have concluded that no humans lived in the cave. A footprint of an eight-year-old boy has been preserved in close proximity to that of a wolf. Did the wolf kill the boy? Or were the prints left 5,000 years apart?

The question arises of who these artists were. Herzog ponders all sorts of ideas about their spirituality, about the (to him) mystical Wagnerian landscape of the Ardèche gorge which features a river curling through a rocky arch (pictured right with French scientist). The title of the film itself feels like no more than a whimsical bit of Freudian editorialising. Were these products really the product of dreams? In the end, nobody knows anything other than what is supplied by the evidence. The archaeologists have concluded that no humans lived in the cave. A footprint of an eight-year-old boy has been preserved in close proximity to that of a wolf. Did the wolf kill the boy? Or were the prints left 5,000 years apart?

Most intriguing of all is the thick cluster of palm prints left in a bright ochre pigment on the face of a rock. From a distance they look like a form of primitive pointillism. From close-up they resemble the work of yet another of Herzog’s obsessives. It’s as if the director has gone back 32 millennia to find himself looking in the mirror.

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Film

Bugonia review - Yorgos Lanthimos on aliens, bees and conspiracy theories

Emma Stone and Jesse Plemons excel in a marvellously deranged black comedy

Bugonia review - Yorgos Lanthimos on aliens, bees and conspiracy theories

Emma Stone and Jesse Plemons excel in a marvellously deranged black comedy

theartsdesk Q&A: director Kelly Reichardt on 'The Mastermind' and reliving the 1970s

The independent filmmaker discusses her intimate heist movie

theartsdesk Q&A: director Kelly Reichardt on 'The Mastermind' and reliving the 1970s

The independent filmmaker discusses her intimate heist movie

Blu-ray: Wendy and Lucy

Down-and-out in rural Oregon: Kelly Reichardt's third feature packs a huge punch

Blu-ray: Wendy and Lucy

Down-and-out in rural Oregon: Kelly Reichardt's third feature packs a huge punch

The Mastermind review - another slim but nourishing slice of Americana from Kelly Reichardt

Josh O'Connor is perfect casting as a cocky middle-class American adrift in the 1970s

The Mastermind review - another slim but nourishing slice of Americana from Kelly Reichardt

Josh O'Connor is perfect casting as a cocky middle-class American adrift in the 1970s

Springsteen: Deliver Me From Nowhere review - the story of the Boss who isn't boss of his own head

A brooding trip on the Bruce Springsteen highway of hard knocks

Springsteen: Deliver Me From Nowhere review - the story of the Boss who isn't boss of his own head

A brooding trip on the Bruce Springsteen highway of hard knocks

The Perfect Neighbor, Netflix review - Florida found-footage documentary is a harrowing watch

Sundance winner chronicles a death that should have been prevented

The Perfect Neighbor, Netflix review - Florida found-footage documentary is a harrowing watch

Sundance winner chronicles a death that should have been prevented

Blu-ray: Le Quai des Brumes

Love twinkles in the gloom of Marcel Carné’s fogbound French poetic realist classic

Blu-ray: Le Quai des Brumes

Love twinkles in the gloom of Marcel Carné’s fogbound French poetic realist classic

Frankenstein review - the Prometheus of the charnel house

Guillermo del Toro is fitfully inspired, but often lost in long-held ambitions

Frankenstein review - the Prometheus of the charnel house

Guillermo del Toro is fitfully inspired, but often lost in long-held ambitions

London Film Festival 2025 - a Korean masterclass in black comedy and a Camus classic effectively realised

New films from Park Chan-wook, Gianfranco Rosi, François Ozon, Ildikó Enyedi and more

London Film Festival 2025 - a Korean masterclass in black comedy and a Camus classic effectively realised

New films from Park Chan-wook, Gianfranco Rosi, François Ozon, Ildikó Enyedi and more

After the Hunt review - muddled #MeToo provocation

Julia Roberts excels despite misfiring drama

After the Hunt review - muddled #MeToo provocation

Julia Roberts excels despite misfiring drama

Ballad of a Small Player review - Colin Farrell's all in as a gambler down on his luck

Conclave director Edward Berger swaps the Vatican for Asia's sin city

Ballad of a Small Player review - Colin Farrell's all in as a gambler down on his luck

Conclave director Edward Berger swaps the Vatican for Asia's sin city

London Film Festival 2025 - Bradley Cooper channels John Bishop, the Boss goes to Nebraska, and a French pandemic

... not to mention Kristen Stewart's directing debut and a punchy prison drama

London Film Festival 2025 - Bradley Cooper channels John Bishop, the Boss goes to Nebraska, and a French pandemic

... not to mention Kristen Stewart's directing debut and a punchy prison drama

Add comment