theartsdesk Q&A: Theatre Producer Elyse Dodgson | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk Q&A: Theatre Producer Elyse Dodgson

theartsdesk Q&A: Theatre Producer Elyse Dodgson

Remembering the unsung heroine of new theatre in translation, who has died aged 73

The Royal Court Theatre has long been a leader in new British drama writing. Thanks to Elyse Dodgson, who has died aged 73, it has built up an international programme like few others in the arts, anywhere. At the theatre, Elyse headed up readings, workshops (in London and abroad), exchanges and writers’ residencies that might have suggested a team of 15 or so but her department was modest in size.

She began full-time at the Royal Court in 1986, working under Max Stafford-Clark for its Young People’s Theatre. More by accident than design she took over the international side in the early 1990s, with the first International Residency – overseas writers coming for a summer stint of workshops and play development – taking place in 1989. The Court now holds an International Playwrights Season periodically: that is, when it feels right to do so rather than adhering to chronological logic.

The 2011 season – just before which Elyse spoke exclusively to theartsdesk – featured work from Latin America and Eastern Europe, including a reading of Pagans, by one of the writers on 2010’s International Residency, Anna Yablonskaya (pictured below). She was shockingly killed in January 2011 in a Moscow airport bomb. (Elyse said here what she could.) New writing from Russia became a central constituent of the Court’s international work in 1999, with Vassily Sigarev’s Plasticine – a Court discovery – winning an Evening Standard Award in 2002.

Elyse Dodgson worked under five Royal Court artistic directors and spent at least 12 weeks a year on the road. If she received a script from another language culture in English, she sent it back. She wasn’t interested in bad English translations. The Court had and has an extraordinarily sophisticated system for assessing plays in the original.

Elyse Dodgson worked under five Royal Court artistic directors and spent at least 12 weeks a year on the road. If she received a script from another language culture in English, she sent it back. She wasn’t interested in bad English translations. The Court had and has an extraordinarily sophisticated system for assessing plays in the original.

Though she lived in Britain for 45 years, she was born in New York and held dual nationality. She was married for 20 years to a German academic, which took her frequently to Berlin where he lived, but which was also where, in 1992, one of the most fertile postwar theatrical exchanges between two European nations began. It culminated in the Court’s most startling talent of the mid-1990s, Sarah Kane (who committed suicide in 1999), becoming one of the most performed contemporary writers not just in Germany but across the world.

Elyse lobbed the pebble in and the pond's ripples are still with us. Here, seven years ago, she told theartsdesk what the Berlin connection was all about, what it led to and what her unique department in Sloane Square really did – and does.

JAMES WOODALL: Can we start with this terrible story about Anna Yablonskaya? How did you find her and what were her achievements? She was only 29…

ELYSE DODGSON: Anna was born and lived in Odessa. But when she started writing plays there was no theatre to support her work locally. She became involved with a Russian writers’ network, who’ve been partners of ours for over 10 years. Through them, we heard about Anna and read some of her early plays with real interest. When she applied to the 2010 International Residency, we were thrilled. She was also a fine poet, and a very accomplished playwright with a completely original voice who depicted her very Ukrainian characters with great humour, detail and love. We had nine writers last summer and everyone loved Anna, full of passion - one of the most talented writers ever to take part. I don’t want to say much about her death. There are no words to describe this barbarism. She'd come to Moscow for the day to collect a prize for the screenplay of Pagans. I was abroad and received dozens of calls from a colleague at the Royal Court to ring him back. I knew something terrible had happened. But this was beyond comprehension. I’m glad she knew how much we appreciated Pagans and she was delighted that we invited her to the Royal Court in April for a staged reading of the play. [It will take place in the Jerwood Theatre Upstairs on 7 April at 5pm.]

How did the International Season begin? Were you in on it at the very start?

The first one was in 1997. We’d just started the International Department. There was a gap of about five weeks in the programming, and I said to then artistic director Stephen Daldry, “Well, we’ve got three great plays from our International Residency programme.” We’d been doing that since 1989. “Why don’t we put the plays into the repertoire and have an international season?” Stephen, being Stephen, said: “And? And? And?” – as he does. “Give me more ideas. How do we do it? We can do readings, we can do this, we can do that…” – and then we needed a funder. So we approached John Studzinski. He’s quite a famous figure now at the Genesis Foundation, who’ve been funding us ever since. We also had some help from the British Council, so we were off.

We did the three plays. At that time, we were still at the Ambassadors [during the Royal Court’s rebuild], so it was in that big space. We had readings and seminars, but everything was close to home: plays from France, Spain and Germany. I couldn’t get a single person to come, almost. No one was interested in seeing new writing in translation. Conor McPherson’s The Weir was playing in our other theatre at the time, the Duke of York’s. I used to go to the returns queue for The Weir and say, “You can come to this for free!” Anything. We had 20 people in the audience and I think it seats about 130. It was very embarrassing.

So how did it pick up momentum to repeat itself?

John Studzinski thought it was fantastic. It had very good reviews. Michael Billington – I always remind him about this – wrote in a piece in The Guardian saying that “the future of new writing is safe in their hands” – meaning our hands – and so critically it was well received. John agreed to carry on supporting it. We didn’t manage to do it again until the year 2000, as we were moving back to Sloane Square. That international season was in May. It was one of the first things we did in the new building. We’d learnt over the years how to do it, that it was really an outcome of all our play development internationally – not the outcome but one of them. It was a real opportunity and we started working further afield, getting better, for instance, at translation. So for that second season, we'd three more years of work under our belt. We started the International Department in 1996, though we’d been doing exchanges since 1993.

What was the thinking behind it? Was it your idea, or…?

No, no, I give full credit to Stephen Daldry. Stephen came to the Royal Court as a great internationalist. He’d been at The Gate [in Notting Hill] and there they did only international work. Max Stafford-Clark had done international work but that was in the Thatcher years, when audiences really wanted to look at Britain. I mean, we looked at Ireland and the occasional international play. But the Royal Court had always been an international theatre under its founder George Devine. That was his dream. The Court put on Beckett and Wole Soyinka. We did all the first English versions of Brecht and Ionesco. It’s always been there in background, and there’ve been phases when it came in and out. When Stephen arrived, he just went for it.

And he was still here in 2000 - he saw the theatre back in to the new premises?

No, officially, he’d left in 1998 and by that time we’d done the first season. Stephen’s successor, Ian Rickson, was always very accommodating and very open, very happy to help us build on what we had.

Is what you do generally focused on the international season each year, or do you spread things about, drop in the odd foreign play where and when you can?

No, not really. It has lots of different strands but at the heart of it, it works in parallel with how the Court works. We’re looking for new writers, we develop their work; we've many relationships around the world where we do long-term workshops, over a three-to-five-year period, to support new writing in other countries but also we have exchanges. Many playwrights from the Court who go on these trips feel that their lives have been changed.

Who in the seasons you’ve done stick in your mind as people who’ve shone and gone on to do really eminent stuff?

By 2002, we were in Russia and our work with writers there has gone on ever since. Vassily Sigarev’s Plasticine was a huge success, directed by Dominic Cooke [the Royal Court’s current artistic director], as was a few years before Fireface, by German playwright Marius von Mayenburg. That’s why Dominic had no problem in becoming an internationalist. Sigarev is a major figure in Russia now, doing a lot in film. We’ve done lots of other Russian work, by the Presnyakov brothers – Oleg and Vladimir – and with Juan Mayorga from Spain, who worked with us in 1998 and who now I would say is probably the leading playwright in Spain. There’s been Marcos Barbosa from Brazil, whom we’re also working with right now. And more recently, Natasha Vorozhbit from Ukraine, who later had her work done at the RSC – she was part of our Russian-language research – and Anupama Chandrasekhar, from India, who writes in English. We’ve done two of her plays and she has a commission, too, for the downstairs theatre.Tell me about the overseas programmes, the work you do in other cities.

We’ve established, at the heart of the work, very long-term programmes: three-to-five years, as I’ve said. Basically we focus on a country, look for partners and I take out a team of playwrights or a playwright and director – always from the Court – then take the group through the different phases of writing a new play for the Court and for whoever the partner is, for their theatre.

And how does it work financially? Is it a co-production in a sense, co-financed by the institutions?

Yes, this is where the Genesis Foundation comes in – who funded our first season – plus the British Council. We also have a relationship with a theatre in Mexico, the Teatro Helénico, and we're on to our third group of writers from there. We’ve brought six writers over to Britain for a week of Mexican readings (Nick Hern Books published the plays). We did one of the plays, On Insomnia and Midnight by Edgar Chías, a co-production with the Cervantino Festival in Mexico, one of the most important drama festivals anywhere. But there’s no fixed way. Every situation will be different. We’ve worked in Cuba, for instance, for eight years – in Havana, with writers from all over the country; and our partners there have been the Consejo Nacional, the National Council for theatre, which is part of the Ministry of Culture.

How easy or difficult is that?

Easy! I mean, yes, always challenging to organise but...

Censorship?

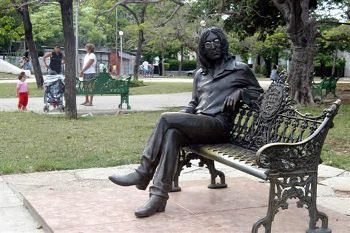

No, no, not for theatre. Well, you know, people can always say that writers might censor themelves, but it’s been very open and it’s really as a result of that we’ve brought work over here. One of the very first plays to come out of that, The Concert by Ulises Rodríguez Febles, was about the time The Beatles were banned in Cuba and just looks at the kind of persecution people who were trying to be like The Beatles or who listened to The Beatles or who wanted to play like The Beatles had to face (statue of John Lennon in Havana pictured above). It won the national play-writing prize in Cuba…

No, no, not for theatre. Well, you know, people can always say that writers might censor themelves, but it’s been very open and it’s really as a result of that we’ve brought work over here. One of the very first plays to come out of that, The Concert by Ulises Rodríguez Febles, was about the time The Beatles were banned in Cuba and just looks at the kind of persecution people who were trying to be like The Beatles or who listened to The Beatles or who wanted to play like The Beatles had to face (statue of John Lennon in Havana pictured above). It won the national play-writing prize in Cuba…

So it was quite political?

Incredibly.

How did it get through?

Because people thought it was really good work. I think the theatre is probably less problematic there, because of its very nature. It’s not TV or radio. Our experience in Cuba has been that the writers have felt pretty free to write. There’s no problem with their associating with a free European theatre such as ours, because it’s the Consejo Nacional who supports them. We’ve had Cuban writers coming here for all those years on our international residency, including one who’s coming this year, called Yunior García Aguilera. One of our youngest writers, he was part of one of our most recent writers’ group.

So how do you make your choices about where to go? Do you head off for somewhere because you know you’ve got a project to develop there, where you have a taste for a place, or are there certain places you just don’t put in your portfolio? You’ve mentioned Brazil, Mexico, Cuba…

Yes, because everyone knows I have a great passion for Latin America! I also have a passion for Eastern Europe. We did an amazing project in the Middle East: we worked in Palestine for 10 years. So we can’t say there’s this one area and not another. One area we haven’t worked in but where we want to is the Far East. We had a Japanese writer last year, two Chinese writers on a residency, but we’ve never had an opportunity to go out there yet. That’s still territory to be explored mutually.

The business of translation in your department must be hectic.

All the plays are channelled through to us by the programme, with a constant, complex process of translation, and we’ve got a very particular, pioneering way of doing it. When we first started, we didn’t have a clue how to, but we always had good translators – like Martin Crimp doing French plays. But now the translators come in to all the rehearsals, and work with the writer and the actors and the director. We’ve been able to nurture and identify people who didn’t know they could be such magnificent translators. We always have a first-draft text. A literal translation is what most other theatres have; they then get a writer who doesn’t know the language to turn it into a play, and we totally oppose that. I think when you’re presenting a writer’s work for the first time, you owe it to the writer to hear his or her voice, and not the voice, which I often hear, of the translator who’s a playwright in his own right.

Over the years, in French, German, Spanish, Russian, Portuguese, we’ve built up an amazing group of translators. Many of them are theatre practitioners anyway, because we think it’s important they know theatre language. Sasha Dugdale, who’s our Russian translator, was working for the British Council in Moscow when we met her: she was a poet. The first play she did was for us but she does them elsewhere now. The Spanish translators are actors. We have a young man, Rory Mullarkey, a playwright and doing Remembrance Day by Aleksey Scherbak, who’s been working at the young writers’ programme and we discovered through one of our directors, Lyndsey Turner, that he’d done a Russian degree, and spoke Russian and Ukrainain. He’s turned out to be wonderful.

What’s special about the current season?

For 2011, we decided to focus on two parts of the world. We chose Pedro Miguel Rozo from Colombia, who came to our first Bogota workshop in 2004. His play, Our Private Life, was a project that didn’t carry on in the same way as others have but Pedro never gave up. He kept on sending us the play and finally we invited him on a residency in 2009. He was still working on the text. Lyndsey Turner eventually directed it and it turned into a great international play, giving us real insight into Colombia but also pushing the form. Aleksey Scherbak came to a 2008 Moscow workshop and originally wanted to write about a desert island or something. We said to him, “What do you really care about? What is urgent for you to be writing about?" He said, “Well, I care about what happens on 16 March every year, when the former Latvian SS march in Riga.” “Oh,” I said, “that’s a Royal Court dream!” We worked on Remembrance Day in Moscow a couple of times, then he came over to London a year ago to work on it more. Plays for selection are discussed, evaluated, agonised over at the script meeting we have once a week, but in the end it’s Dominic’s decision.

You’ve had 25 years at the Royal Court. How did you start?

I was once an actress in the 1960s, in the Brighton Combination, one of the first British fringe theatres. I grew up in Brooklyn, where I was born, in Brighton Beach. Then, in England, I had my children [with first husband John Dodgson] and decided to become a drama teacher, which I loved for many, many years. I did a project called Motherland, one of the first verbatim projects, at the Vauxhall Manor School, which was 85 per cent Afro-Caribbean girls. It was about daughters interviewing their mothers about coming to England. Max saw it. When the job came up for the Young People’s Theatre, I took a huge drop in salary and never looked back. Then, when Stephen came in in 1991 or 1992, his internationalism encouraged us to look abroad.

You became very closely involved with a group of young drama-makers in Berlin, now well known in Germany and internationally. The centre point was English writing and the Royal Court, and no doubt the process continues. How did that all start – and what has been the quality and success of this exchange?

It all goes back to Stephen again. I used to say he was the wind beneath my wings and I’d still say it. He was passionate about German theatre, so when he was trying to create an international buzz, he was finding his feet. He’d come from the Gate; it was a huge leap. He was very good at forging relationships. He went to the Goethe Institute and managed to find five translated plays, which they selected. This was in 1992. And we did this week of German readings in the upstairs theatre. One of them was Dea Loher’s first play, Olga’s Room. But these plays were’t really the Royal Court’s choice. Still, there were lots of meetings and talks and so on. I had a particular interest in Berlin because I was married to a Berliner, so I spent a lot of time there and was especially excited to meet new theatre people.

I approached every major theatre with a bunch of Royal Court plays, which included all those then in the repertoire, and therefore were some really major playwrights. But nobody wanted them. I went to the Berliner Ensemble, because I knew one of the dramaturgs; he’d been part of our first German week. They flirted with us for a bit, then came back with: how dare we propose to do this naturalistic, this social-realistic… whatever it was… stuff in the home of Bertolt Brecht and Heiner Müller? [Müller was a former East German playwright and director, who died in 1995.] Finally, I approached a man called Michael Eberth, chief dramaturg at Berlin’s Deutsches Theater. He was a complete Anglophile, knew the work and loved it. He said, "We have this thing called the Baracke we hardly ever use. Why don’t we bring the writers over here and see how it works? We'll translate the plays." So they made a selection. This was in 1994. They chose Martin Crimp, David Greig, Meredith Oakes, Kevin Elyot and David Spencer, who was based in Berlin. They did the readings and I’ll never forget the very first night. We didn’t think, really, anyone would come. But there used to be this tunnel that went from the main café of the green room at the Deutsches Theater to the Baracke, and I remember walking through it with Michael, and someone came running over and said it was absolutely packed. There was a feeling that this was going to work. It was a great event and inspirational for what was to come.

I approached every major theatre with a bunch of Royal Court plays, which included all those then in the repertoire, and therefore were some really major playwrights. But nobody wanted them. I went to the Berliner Ensemble, because I knew one of the dramaturgs; he’d been part of our first German week. They flirted with us for a bit, then came back with: how dare we propose to do this naturalistic, this social-realistic… whatever it was… stuff in the home of Bertolt Brecht and Heiner Müller? [Müller was a former East German playwright and director, who died in 1995.] Finally, I approached a man called Michael Eberth, chief dramaturg at Berlin’s Deutsches Theater. He was a complete Anglophile, knew the work and loved it. He said, "We have this thing called the Baracke we hardly ever use. Why don’t we bring the writers over here and see how it works? We'll translate the plays." So they made a selection. This was in 1994. They chose Martin Crimp, David Greig, Meredith Oakes, Kevin Elyot and David Spencer, who was based in Berlin. They did the readings and I’ll never forget the very first night. We didn’t think, really, anyone would come. But there used to be this tunnel that went from the main café of the green room at the Deutsches Theater to the Baracke, and I remember walking through it with Michael, and someone came running over and said it was absolutely packed. There was a feeling that this was going to work. It was a great event and inspirational for what was to come.

We never again let anyone else choose the plays, as we’d got this momentum and this relationship going with the German writers. The next round included Dea Loher, Klaus Chatten, Anna Langhoff, all of them published by Nick Hern. Two years later, Michael Eberth said, “I’m handing the Baracke over to these young boys. They’ve just come out of drama school.” I’ve called them “the boys” ever since. Anyway, one of them, a director, Thomas Ostermeier, was ill, so I went to lunch in one of those Jewish restaurants in East Berlin with Michael and Jens Hillje, an aspiring dramaturg, and very, very brilliant and sensitive. That’s when it was clear how interested in our work they were. David Harrower’s Knives in Hens was one of the plays which Thomas decided to produce almost immediately. Then, it was Phyllis Nagy, Mark Ravenhill and Sarah Kane.

So the Baracke discovered something these young Germans didn’t have in their own culture – these fresh, spontaneous, dark, rude, very English plays. What happened?

The Baracke started to produce them. [Mark Ravenhill’s] Shopping and Fucking (Berlin production pictured above) is still playing in Berlin [at the Schaubühne: Ostermeier, Hillje and a team of like-minded theatre people began to run the Kurfürstendamm venue in 1999, taking with them from the Baracke a repertoire of Royal Court plays]. In my opinion, the combination of some great, great writers and a wonderful director, like Thomas, was sensational.

Did you take great pleasure in all of this?

We do exchanges with theatres all over the world. What became the Schaubühne-Royal Court thing wasn’t an exchange. It was sister and brother. There was a lot more dialogue going on between all practitioners at both the Court and the Schaubühne than there ever was between us and other theatres. It’s an established relationship we can rely on, but we don’t quite have the same network now as we had then. Thomas has a great vision. He’s not a director who doesn’t know how to work with a writer. There’s something magical about what he does. I once invited him to direct a reading here of Marius von Mayenburg’s Fireface, during one of our return exchanges. Our actors were both fascinated and shocked because he had such a different way of working. It’s much more authoritarian than what our directors do.

Sarah Kane became a key figure in this exchange, because the Germans loved Blasted [premiered upstairs at the Court in January 1995], they loved her writing, and were also compelled by her difficult life and personality. It took Ostermeier many years before he could do Blasted at the Schaubühne and the veteran Peter Zadek got to do Cleansed first in German. But eventually all five of her plays were in the Schaubühne repertoire at the same time. Sarah became a kind of cult figure there and in Germany as a whole. What did you see and know, behind the cult, the fame, or notoriety?

I was just someone on the sidelines who got to know her when she was doing Blasted. This was before the International Department had really started. Sarah needed a lot of support during Blasted. She had to go into hiding. I also did a lot of the post-show talks with her and got to know her more then. And let’s be clear: she was young enough to be my daughter. Once the International Department was up and running, I asked her to be one of the writers who’d come and help us out. During the 1998 residency, she was outstanding. She agreed to do a two-day workshop on it and I didn’t know, in advance, what she did: she was a young writer. What was she going to be like as a teacher? She was unbelievable. In the seven or eight years after she died, I never went near what she did, it was so good. She’d ask the writers what their greatest fear was, and there was a lot of random work, throwing words into a circle. It was very much about how you use your personal experience, what’s out there, what you have to discover, how she stimulated herself as a writer. She put everyone through a particular day of work and then everyone had to create a two-minute monologue out of all the stimuli they'd gathered. I still have mine, as I took part. And she got up and read to us one of the speeches from Crave, which she’d just written but nobody had then of course seen. It was a life-changing workshop for those writers. She was the most glorious teacher.

But in that year, 1998, she was also quite ill.

She was ill from the start. It never manifested itself in the work, ever. But I came close to her and so I knew her well, her problems. I don’t want to glorify her, but what was so magnificent was that she was always quite open about her state of mind, what she felt about life – that was very hard sometimes. It was incredibly hard for her, but we also wanted to be able to do the right thing. She'd also come into so much success by then, it was difficult to work out what was going wrong. She had help. She was very aware of what was going on. Her international profile, now, is astonishing and there’s nowhere in the world I go where they don’t try and get me to talk about her. I’m fine to talk about Sarah’s contribution but not about the personal stuff, which they always try and do.

Is she any more “liked” now, in Britain, do you think?

Someone at the Goethe Institute said to me recently that they had read that it was Germany that had made her a superstar, not England, but I don’t think that’s true. The Royal Court was her theatre. We produced the most pure and beautiful productions of her work, the ones she was present at, in the rehearsals. She was absolutely meticulous. She knew about theatre, how she wanted her work produced. She was there all the time. And by the time of Crave and 4.48 Psychosis, she was clearly being seen as a major emerging figure.

Finally, Elyse, any tidbits about you – your antecedents, your origins?

My parents were Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe. My mother was actually born in the States. Her family was from Lithuania. My father was from the Ukraine. My family name was Kramer, but actually it wasn’t! I wanted to find out for sure, so went a couple of years ago to the town in the Ukraine where my father was born and I couldn’t find a thing because there were virtually no Jews left, of course. More interestingly, I came back from the Ukraine just a couple of weeks ago and had wound up being interviewed on national TV: they asked me if my father had spoken Ukrainian and I said he didn’t even know he was Ukrainian! Because then it was Austria-Hungary. One of his parents I think was a Kramer, but in fact – I checked on the immigration certificate – he came to the US aged three as Solomon Rosenrauch.

I went to university in Chicago but wanted to act, so for that I reckoned I needed British training, so I went to the Guildhall in 1966. On my very first day in England I went to the Royal Court – I knew about it of course. I sat in the gods and saw a revival of Ann Jellicoe’s The Knack. I always loved this theatre and saw everything. When Max interviewed me to run the Young People’s Theatre, I sat in his office, and he used to have these posters of the Royal Court shows on the walls, and he asked me: “So, what have you seen here?” I looked at the posters and answered: “Everything!” So I guess I was always going to get the job.

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Theatre

The Maids, Donmar Warehouse review - vibrant cast lost in a spectacular-looking fever dream

Kip Williams revises Genet, with little gained in the update except eye-popping visuals

The Maids, Donmar Warehouse review - vibrant cast lost in a spectacular-looking fever dream

Kip Williams revises Genet, with little gained in the update except eye-popping visuals

Ragdoll, Jermyn Street Theatre review - compelling and emotionally truthful

Katherine Moar returns with a Patty Hearst-inspired follow up to her debut hit 'Farm Hall'

Ragdoll, Jermyn Street Theatre review - compelling and emotionally truthful

Katherine Moar returns with a Patty Hearst-inspired follow up to her debut hit 'Farm Hall'

Troilus and Cressida, Globe Theatre review - a 'problem play' with added problems

Raucous and carnivalesque, but also ugly and incomprehensible

Troilus and Cressida, Globe Theatre review - a 'problem play' with added problems

Raucous and carnivalesque, but also ugly and incomprehensible

Clarkston, Trafalgar Theatre review - two lads on a road to nowhere

Netflix star, Joe Locke, is the selling point of a production that needs one

Clarkston, Trafalgar Theatre review - two lads on a road to nowhere

Netflix star, Joe Locke, is the selling point of a production that needs one

Ghost Stories, Peacock Theatre review - spirited staging but short on scares

Impressive spectacle saves an ageing show in an unsuitable venue

Ghost Stories, Peacock Theatre review - spirited staging but short on scares

Impressive spectacle saves an ageing show in an unsuitable venue

Hamlet, National Theatre review - turning tragedy to comedy is no joke

Hiran Abeyeskera’s childlike prince falls flat in a mixed production

Hamlet, National Theatre review - turning tragedy to comedy is no joke

Hiran Abeyeskera’s childlike prince falls flat in a mixed production

Rohtko, Barbican review - postmodern meditation on fake and authentic art is less than the sum of its parts

Łukasz Twarkowski's production dazzles without illuminating

Rohtko, Barbican review - postmodern meditation on fake and authentic art is less than the sum of its parts

Łukasz Twarkowski's production dazzles without illuminating

Lee, Park Theatre review - Lee Krasner looks back on her life as an artist

Informative and interesting, the play's format limits its potential

Lee, Park Theatre review - Lee Krasner looks back on her life as an artist

Informative and interesting, the play's format limits its potential

Measure for Measure, RSC, Stratford review - 'problem play' has no problem with relevance

Shakespeare, in this adaptation, is at his most perceptive

Measure for Measure, RSC, Stratford review - 'problem play' has no problem with relevance

Shakespeare, in this adaptation, is at his most perceptive

The Importance of Being Earnest, Noël Coward Theatre review - dazzling and delightful queer fest

West End transfer of National Theatre hit stars Stephen Fry and Olly Alexander

The Importance of Being Earnest, Noël Coward Theatre review - dazzling and delightful queer fest

West End transfer of National Theatre hit stars Stephen Fry and Olly Alexander

Get Down Tonight, Charing Cross Theatre review - glitz and hits from the 70s

If you love the songs of KC and the Sunshine Band, Please Do Go!

Get Down Tonight, Charing Cross Theatre review - glitz and hits from the 70s

If you love the songs of KC and the Sunshine Band, Please Do Go!

Punch, Apollo Theatre review - powerful play about the strength of redemption

James Graham's play transfixes the audience at every stage

Punch, Apollo Theatre review - powerful play about the strength of redemption

James Graham's play transfixes the audience at every stage

Add comment