As the young waitress said in the restaurant where we ate after last night’s world premiere of Ashley Page’s Alice in Glasgow, she hadn’t ever been to ballet, but she was tempted to go for this - “It’s Alice after all, isn’t it? Wonderland. I’d love to see Wonderland.” The kind of new audience that any company should kill for.

And my friend said, sadly, yes, that’s what we’d also supposed it would be. "So shall I go?" she said. We said, um, you’re right. Ballet is the one place where you really can hope to see Wonderland, the unsayable, the merely imaginable. But there is always the danger that you’ll be put off ballet if you see something that messed it up. Three hearts sank together.

This production starts from a much firmer premise than Christopher Wheeldon’s failure de luxe at the Royal Ballet last month: the idea that Lewis Carroll, real name Charles Dodgson, was as much a photographer as an author, and that his fantastical writing came from his dissociative habit of looking at life through a lens. Alice therefore - we surmise - exists both in front of the lens (the real Alice) and behind Dodgson’s (the vision he wishes to shape of her).

To further this fruitful idea, the stage is dominated at the start by a gigantic bellows camera, which after Alice dives through the lens, splits open to show a black box behind which looms a large antique mahogany slide-camera frame. This is a very clever setting for a dual layering of activity, the associative memory provided by projections in the frame, and the “real” episodes on the stage.

To further this fruitful idea, the stage is dominated at the start by a gigantic bellows camera, which after Alice dives through the lens, splits open to show a black box behind which looms a large antique mahogany slide-camera frame. This is a very clever setting for a dual layering of activity, the associative memory provided by projections in the frame, and the “real” episodes on the stage.

And it’s really quite like Monty Python’s old tricks; superb costuming by Antony McDonald - the suit of Hearts are triumphs of sharp, fantastical tailoring (see the gallery below) - their very real presence complemented by the alluringly surreal video work of Annemarie Woods, acting like the Terry Gilliam in the Python team, sneaking in her strange visions behind the action in the photo frame.

All goes very well in the design department - it’s in the choreographic, dramaturgical and musical areas that things rapidly become unstuck. Page, like Wheeldon in London, has relied too much upon his designer, McDonald, to package the favourite episodes, and on the composer to provide yards of musical lining, as he has no linear drama to provide for his part. But the composer, Robert Moran in this instance, can work as hard and as ingeniously as he might to provide yards of music for Lobster Quadrilles, Humpty Dumpty (half baby, half egg, all silly), Tweedledum and Tweedledee (schoolgirls) and whathaveyou, but he is seriously up Indecision Creek if the co-directors show no belief in what the various dance episodes are adding up to. And for long periods one feels Moran killing time with cool, arrhythmic percussiveness - lots of marimbas, wood blocks, drums - in between strong waltzes and Pulcinella-like courtliness, just waiting for an instruction about an emotional destination.

The reason the public loves Alice is because she’s an enigmatic mirror for their imaginings. By contrast, Charles Dodgson is stuck with a modern reputation as a faintly weird man who liked to photograph a pre-pubescent child naked. Frankly, had Page decided to do Alice as a variant of Humbert Humbert and Lolita he’d have both served his designers better and given himself a real theatrical focus of emotional immediacy.

As it is, this is an endurance test of a ballet, two hours plus the interval, trying for children and adults alike, in which charm goes begging yet risks are refused. Alice, danced by the exquisitely elegant and intelligent Sophie Martin, isn’t the true heart of the ballet because her series of pas de deux with Dodgson travel nowhere, despite her growing older. The third duet is the outstanding one, sincere and honest, two people in frank sexual imbalance, he yearning for her, she tempted but refusing - the best of Page’s work in the night. But Dodgson feels like the missing centre of this character ballet - despite his omnipresence, Page consigns the inexpressive Eric Cavallari to a bland proto-Classical idiom that yields no insight into who Dodgson might be.

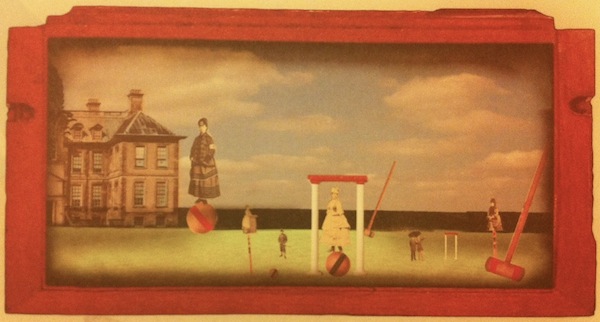

Yet what Annemarie Woods’s strange and succulent visions in the back frame (a drawing of one, pictured left) mesmerisingly suggest is the rich confusion, the unorthodox interior landscape, of a young, awkward Victorian man obsessed with the sexual wonderland of a girl and her changes from an easily understood child into a completely baffling young woman. Often it’s the ocean that we see in her Dalí-esque visions, peppered with little bobbing Alice heads at different ages, or proudly bearing an approaching sailboat with her standing on it like Botticelli’s Venus, but invested with a lobster crown and a jam tart shield, a parodic Britannia, queen of the ungovernable currents inside Dodgson’s head. Woods does seem to have the measure of the book in a way Page doesn’t.

Yet what Annemarie Woods’s strange and succulent visions in the back frame (a drawing of one, pictured left) mesmerisingly suggest is the rich confusion, the unorthodox interior landscape, of a young, awkward Victorian man obsessed with the sexual wonderland of a girl and her changes from an easily understood child into a completely baffling young woman. Often it’s the ocean that we see in her Dalí-esque visions, peppered with little bobbing Alice heads at different ages, or proudly bearing an approaching sailboat with her standing on it like Botticelli’s Venus, but invested with a lobster crown and a jam tart shield, a parodic Britannia, queen of the ungovernable currents inside Dodgson’s head. Woods does seem to have the measure of the book in a way Page doesn’t.

Here and there one catches a glimpse of the much more interesting ballet Page might have done had he been braver, in the echoes he draws with the dark male characters of MacMillan’s ballets that he himself once played, from Tybalt to the King of the South in Prince of the Pagodas. The tangoing Caterpillar, with his huge mushroom and dangerous hookah, is quite a sleazy menace to a young girl. The ménage à trois of the Mad Hatter, March Hare and Dormouse has associations with two men oppressing a little girl in her pyjamas for sinister reasons. The Jabberwock, a fearsome-looking axeman with a black executioner’s block covering his head, is unmasked as a fevered, almost vampiric young man.

The visions they present are not as vanilla as the dance they do. This production strongly suggests something undeveloped, film left in the camera, visions sanitised in the processing. All add up to a long, antiseptic and resistible experience. Not Wonderland. Off with their heads.

OVERLEAF: ALICE'S ADVENTURES ON STAGE AND SCREEN

Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, Royal Ballet. Even the best butter would not help this plot-less evening

Alice's Adventures Under Ground, Barbican. Gerald Barry's crazy velocity berserks both Alice books in rude style

Alice in Wonderland. Tim Burton takes on the fantasy classic

Alice in Wonderland. Tim Burton takes on the fantasy classic

Alice in Wonderland, BBCSO, Brönnimann, Barbican. A curious tale gets a riotous operatic telling from composer Unsuk Chin

Alice Through the Looking Glass. Mia Wasikowska (pictured), Helena Bonham Carter and Johnny Depp back in inventive if unfaithful Carroll sequel

Jan Švankmajer's Alice. The great Czech animator's remarkable first full-length film

wonder.land, National Theatre. Damon Albarn’s Alice musical has fun graphics, but a banal and didactic storyline

Add comment