Lucian Freud, who died aged 88 at his west London home on Wednesday, was often described as Britain's greatest living artist. In the six decades he was active, figurative painting went in and out of fashion - though mostly it was out - but Freud remained resolutely outside and beyond fashion. As both an art world grandee and something of a celebrity, he really had no rival, though perhaps David Hockney, still alive and 15 years his junior, came closest. Freud, however, had a very different way of looking: cooler, harder, more penetrative. Below, four writers pay their personal tributes.

Fisun Güner

Lucian Freud’s 1984 Hayward Gallery retrospective was my first encounter with the artist. It was also the first exhibition by a living artist I had ever attended, and the exposure completely blew me away. I felt compelled to return - and the second time was on my own (my sister had found the images too brutal, too cruel, and she expressed her distaste) - and to spend even longer with each of these wonderfully revealing, raw portraits.

Freud had yet to paint his huge Leigh Bowery pictures, or Sue, the benefits supervisor (his 1995 canvas, Benefits Supervisor Sleeping [see gallery below] sold for £17.2million in 2008, setting a world record for a living artist). I don’t recall encountering any sitters of exceptional girth. His taste for what one might call the grotesque exaggerations of the human form was yet to fully reveal itself. Much later, at both the Tate retrospective of 2002, and the Wallace Collection’s exhibition of 2004, I was rather less in awe.

His more recent paintings at the Wallace seemed to show an artist who’d become far more interested in his dogs and his horses and rather neglectful of the human figure: his four-legged friends were painted with far more precision, care and feeling.

It’s probably true that Freud peaked rather early, and for me his earliest works are the most remarkable. His intricate, stylised and meticulously detailed paintings from the Forties and early Fifties, of delicate lemon sprigs and splayed dead birds and threatening cacti (these inanimate things all expressing a sense of spiky postwar angst) are his most seductive paintings. And one of the things that makes them so remarkable is the exquisite colour, their sheer vibrancy. Who would normally associate Freud with such an intensely vivid and seductive palette, all contained in such precise, careful forms? A 2008 exhibition at Hazlitt Holland-Hibbert focused on works of this period, brilliant small-scale paintings from 1939 to 1954 - and I was freshly blown away.

It’s probably true that Freud peaked rather early, and for me his earliest works are the most remarkable. His intricate, stylised and meticulously detailed paintings from the Forties and early Fifties, of delicate lemon sprigs and splayed dead birds and threatening cacti (these inanimate things all expressing a sense of spiky postwar angst) are his most seductive paintings. And one of the things that makes them so remarkable is the exquisite colour, their sheer vibrancy. Who would normally associate Freud with such an intensely vivid and seductive palette, all contained in such precise, careful forms? A 2008 exhibition at Hazlitt Holland-Hibbert focused on works of this period, brilliant small-scale paintings from 1939 to 1954 - and I was freshly blown away.

Freud was the artist who first got me thinking seriously about art, and about the possibilities of paint. Just a few years later, the Hayward put on a Richard Long exhibition. I went along to that too, and I suspect my life might have taken a different turn had that exhibition been my first encounter with a living artist. (Pictured above right: Woman with a Tulip, 1945.)

Marina Vaizey

Painting, and representational painting, in spite of all the theories and all the varied media that have absorbed artists in the pre- and postwar periods, has never gone away, even if we are in thrall to light bulbs going on and off, exploded sheds, inside-out houses: the art world now has room for everything. But Lucian Freud, although he would have abhorred the notion that in any way he was a crusader, almost single-handedly kept the whole idea of the significance of painting the world as one person saw it alive and at the centre of things.

The rumours and myths that surrounded him (not to mention the irresistible allure of his surname) were potent additions to the fascination that both his art and his life exerted on an increasingly wide public: the gambling, the obsessive rituals, the idiosyncratic behaviour, the adoration of his circle and, of course, the love of dogs, so often portrayed in touching portraits, and the love of women (and their love for him). One of the funniest moments for me was a marvellous supper party with some of the best painters of the time, about 20 years ago, when the entire evening was occupied with speculation about how many children Freud had fathered, and/or acknowledged. One artist insisted the magical number must be at least 35.

It is rather moving to think of Freud at the Slade, with Sir William Coldstream at the helm: under an apparently conventional carapace, and operating at the heart of the art establishment, he was a wonderfully wild character, and an obsessive realist devoted to the human figure.

Freud made headlines and the gossip columns. His non-speaking relationship with his brother Clement, and his penchant not just for beauties, but relationships which were temporarily obsessive – most of the women knew the rules - ensured that he became probably the only London-based artist since Bloomsbury and the Vorticists whose life was as much a basis of gossip as his art was admired.

He really burst onto the international scene with the Arts Council Hayward exhibition of 1974. He was courted continually by dealers, several of whom acted with the utmost discretion doing very well for both Freud’s art and their bank accounts, too. He was ruthless in his relationships with friends and foes.

He really burst onto the international scene with the Arts Council Hayward exhibition of 1974. He was courted continually by dealers, several of whom acted with the utmost discretion doing very well for both Freud’s art and their bank accounts, too. He was ruthless in his relationships with friends and foes.

His emotional life is also visible in his paintings of women, many of them unidentified in public, but of course known about. He had his court and commanded intense loyalty, and in spite of all the gossip was also in many respects a very effective control freak. He is also unusual in being not only critically but also commercially successful, perhaps the only current British parallel being David Hockney.

The establishment adored him, perhaps because his life would not have been out of place in the 18th century, among the (very) upper classes. He painted dukes and duchesses, Kate Moss and the Queen, as well as the grossly obese and charismatic performer Leigh Bowery and the overweight benefit inspector. His view of flesh was certainly warts and all, unflinching in his acute observation, the opposite of flattering. But he also, on a personal level, enjoyed throwing dust in the eyes of those who thought they knew him. (Pictured above left: Large Interior, W11, 1983.)

Josh Spero

My first prolonged encounter with Lucian Freud's fleshy magnificence was in Venice, off St Mark's Square, where he was having a major retrospective in 2005. I had already spent several days on this long holiday consuming art, mainly classical and Renaissance: pale nudes reclining on tidy couches, epic marble heroes standing more than life-size. It had left me overwhelmed and apathetic, an academic creeper tightening around my bones.

I'd like to say that Freud swept away the dust with one dramatic stroke-painting sweep of the arm, but it was the gradual progression through 50 years of his work, peppered with some early, uninspiring pictures more interested in the walls than the faces (which my companion found oddly marvellous), which refreshed me. Here was life! Tortured, implacable, unashamed, bare life.

I'd like to say that Freud swept away the dust with one dramatic stroke-painting sweep of the arm, but it was the gradual progression through 50 years of his work, peppered with some early, uninspiring pictures more interested in the walls than the faces (which my companion found oddly marvellous), which refreshed me. Here was life! Tortured, implacable, unashamed, bare life.

The treks through the Louvre and the churches of Venice suddenly made more sense. Between the Impressionists and Freud, art had moved away from the representation of the human form, but Freud returned with clarity and a lack of reverence to the previously dominant tradition of Western art. He had learnt from Dürer and the Northern Europeans about detail, and from the Italians about beauty. He had also learnt from Bacon and the moderns about how the act of painting, not just its subject, could be its own expression.

Freud restored the human to art but without succumbing to dry tradition. No, he innovated and gave us people as we know them, not the ideal figures of his predecessors but - whether lumpen or lithe, grand or low - real human beings. That was the light of Lucian Freud. (Pictured above right: Reflection with Two Children, 1955.)

Jasper Rees

About a decade ago I interviewed David Storey, the playwright and novelist, who recalled his time as an art student at the Slade in the 1950s where Freud was a tutor: "Lucian Freud taught there but he conspicuously didn't teach me. He taught the life class. He would go round the class and go to each easel and he'd come to me and then he'd disappear behind me, and nothing would happen for ages. I thought he'd either completely disappeared or left the room or something, and I turned round and his face was here. Took me out of my fucking wits. He didn't say a word. That happened every occasion so I got the message that somehow he wasn't connecting with what I was endeavouring to do.

He was very likeable because when I became president of the Slade Society I had to organise the annual Slade dinner which was a rather formal and frightening affair. Distinguished guests were invited from the Arts Council and the art world, including people like Stanley Spencer. It was held in one of the life rooms.

He was very likeable because when I became president of the Slade Society I had to organise the annual Slade dinner which was a rather formal and frightening affair. Distinguished guests were invited from the Arts Council and the art world, including people like Stanley Spencer. It was held in one of the life rooms.

Freud came to me beforehand and said he'd bought a ticket for himself and his wife and his wife couldn't come but would I mind if he brought his dog instead. I said, 'Yes, that's fine,' thinking that'll liven things up. I then forgot about it. There was a pre-dinner formal drinks and I had borrowed evening dress and stuff - William Coldstream was the principal - in his study for the distinguished guests. We were all gathered there when the door opened and a fucking great dog came in slavering. And it was choking because there was a rope round its neck. It kept on coming in and the rope kept coming in - just yards and yards of rope. Everybody was standing back from the thing. It was clearly completely out of control. Eventually at the end of this long rope came Freud.

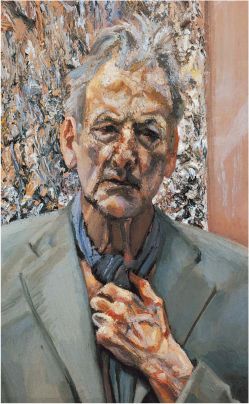

I thought he was doing it on purpose and went up to him and said, 'Can you control it?' He said, 'No,' as though that was an absurd question. Why on earth are you asking such a ridiculous question? It cleared the room in no time. I didn't realise where Freud was sitting. I sat down at the top table and to my horror Freud was sitting opposite me and sitting next to him was the fucking dog. It was sitting on the chair and when the food was served it was put in front of him and it ate off the plate. And of course no one wanted to say they were stuffy arseholes so no one could complain." (Pictured above left: Reflection Self-Portrait, 1985.)

Click an image to enter gallery

- Dead Heron, 1945

- Girl with a Kitten, 1947

- Girl with White Dog, 1951

- Large Interior, 1969

- Reflection (Self-portrait), 1981

- Two Men, 1987/88

- Leigh on a Green Sofa, 1993

- Benefits Supervisor Sleeping, 1995

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_125_x_125_/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=3oW-Y84i)

Add comment