It is all too easy to be cynical about the ballet version of Don Quixote. With almost no part for the title character, it is a 19th-century Russian take on faux-Spanish dancing, a farce in which the barber Basilio longs for the charming Kitri, while her father wants her to marry a rich fop. As the Radio Times used to say, “Much hilarity ensues.”

Well, actually, it rarely does, for funny ballets are few and far between. Frederick Ashton achieved it in his miraculous La fille mal gardée; Jerome Robbins’s The Concert can make a grown (wo)man weep with happiness on the right night; Baryshnikov even managed to make his 1978 Don Q for American Ballet Theater a delightful romp. (This is the one the Royal Ballet revived in the 1990s.) But it’s a tough one. The music, by Ludwig Minkus, is of the oompah variety. The lead dancers need steely skill, precision comic timing, and bags of charm – not a small ask.

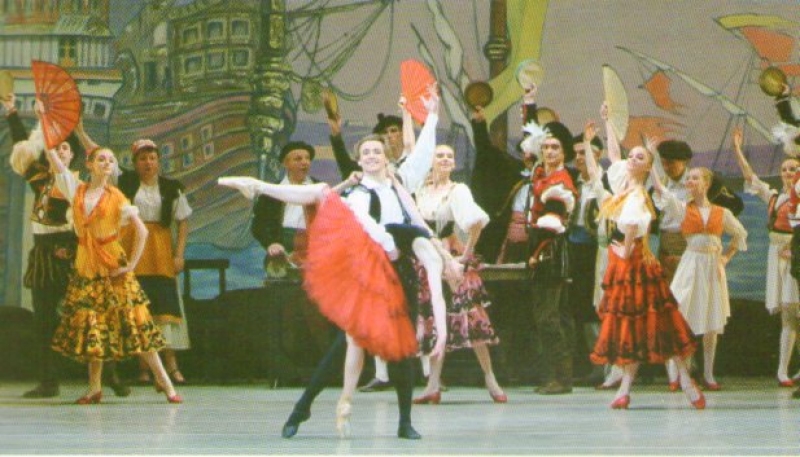

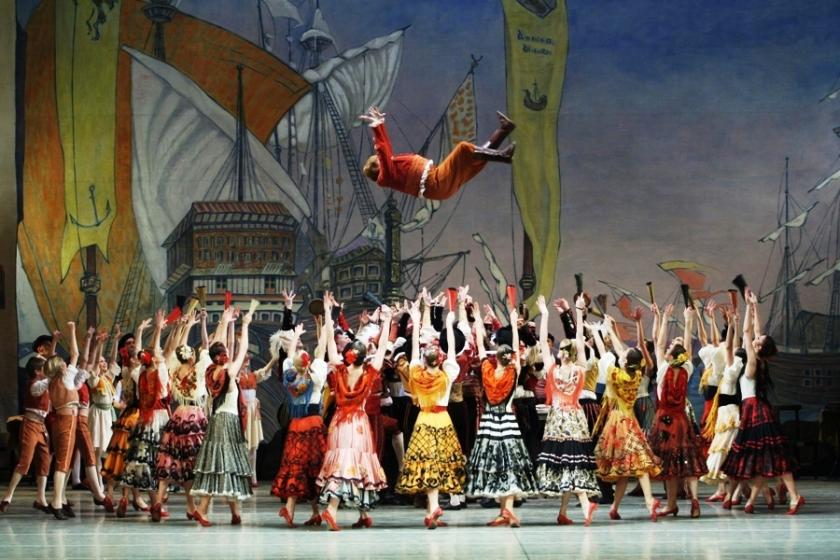

The Mariinsky’s version is preserved in aspic, being the 1900 recreation of Petipa's original 1869 piece, done by the ballet master Alexander Gorsky. In its own way, this is fascinating. We are back, not in the Soviet era that their Swan Lake recalls, but in the 19th-century days of epic scenery painters. It is entirely possible, when looking at the great painted backdrop of a harbour with its splendid flags and careful perspective, or at the corps’s costumes, a curious melange of cod-Elizabethan slashed doublets with Spanish add-ons, to imagine Henry Irving or Beerbohm Tree sashaying out in something similar (pictured right, Henry Ainslie as Faust in a very similar male costume). For those historically inclined, it is an interesting immersion in a period most of us in the West have never experienced.

The Mariinsky’s version is preserved in aspic, being the 1900 recreation of Petipa's original 1869 piece, done by the ballet master Alexander Gorsky. In its own way, this is fascinating. We are back, not in the Soviet era that their Swan Lake recalls, but in the 19th-century days of epic scenery painters. It is entirely possible, when looking at the great painted backdrop of a harbour with its splendid flags and careful perspective, or at the corps’s costumes, a curious melange of cod-Elizabethan slashed doublets with Spanish add-ons, to imagine Henry Irving or Beerbohm Tree sashaying out in something similar (pictured right, Henry Ainslie as Faust in a very similar male costume). For those historically inclined, it is an interesting immersion in a period most of us in the West have never experienced.

If this historical excursus makes it sound like I’m tiptoeing around the central question – did the lead dancers have, as I outlined, “steely skill, precision comic timing, and bags of charm”? – well, I am a bit. The performances were taken by a husband-and-wife team, Denis and Anastasia Matvienko. Denis (I will first-name them, for simplicity’s sake) has, unusually for Russia, freelanced for some years, before becoming a principal at the Mariinsky a couple of years ago. He has an unforced charm of personality that carries well; his turns can be spectacular; and he is an equally spectacular partner, solid and reassuring to his partner and the audience alike. Anastasia is still a soloist, and she was not yet comfortable with this fiendish part. But more importantly than technique, one never received the sense that for her dancing has any higher purpose than its gymnastic components.

Both Matvienkos were eclipsed in Act I by the stellar Ekaterina Kondaurova (who had dazzled everyone as the Firebird last week) and the young soloist Alexander Sergeev (who will appear later this week in Balanchine's Scotch Symphony - hurry and get your tickets now!). Sergeev has that nameless thing that Anastasia so far lacks, the ability to shape a phrase, to surprise the viewer each time, even as a step is repeated. Kondaurova and Sergeev were worth the price of admission alone, and the audience knew it, roaring its approval despite their relatively circumscribed parts.

The Mariinsky’s commitment to character dancing, too, should be commended. Too often in the West, the character dances are a time when audiences begin to try and remember if they need to stop and buy yoghurt on the way home, and was Johnny’s football kit put through the wash. The Russian companies have always given them full due, and, in particular, Islom Baimuradow as the Gypsy King, and Kamil Iangurazov, dancing a fandango in the last act, deserved the acclaim they received – they gave truly wholehearted performances.

The Mariinsky’s commitment to character dancing, too, should be commended. Too often in the West, the character dances are a time when audiences begin to try and remember if they need to stop and buy yoghurt on the way home, and was Johnny’s football kit put through the wash. The Russian companies have always given them full due, and, in particular, Islom Baimuradow as the Gypsy King, and Kamil Iangurazov, dancing a fandango in the last act, deserved the acclaim they received – they gave truly wholehearted performances.

It is rare, I think, to come out of Don Q thinking that everything was perfect - it's just not that kind of ballet. It is a curate’s egg, but with a yolk of gold. That the Mariinsky have not entirely managed to unscramble it is no shame. Few companies ever have.

Add comment