BBC Proms: National Youth Orchestra, Jurowski/ Nigel Kennedy | reviews, news & interviews

BBC Proms: National Youth Orchestra, Jurowski/ Nigel Kennedy

BBC Proms: National Youth Orchestra, Jurowski/ Nigel Kennedy

This year's most youthful Prom paints a joyful picture of the future of British music

Youth was everywhere to be seen at the Proms last night. Whether in the massed ranks of Britain’s National Youth Orchestra, soloist Ben Grosvenor (even younger than the precocious Benjamin Britten when he debuted his own Piano Concerto in 1938), Prokofiev’s Romeo and Juliet, or DJ-turned-composer Gabriel Prokofiev, it was an evening celebrating the scope of the teenage experience. Even the Late Night Prom joined in the party, coming courtesy of Nigel Kennedy, still surely the oldest and most defiant teenager in classical music.

It doesn’t get much more self-consciously youthful and hip than Gabriel Prokofiev’s Concerto for Turntables and Orchestra. Playing with a dialogue between recorded and live sound it demands that the soloist (here the swift-fingered DJ Switch, sporting his very smartest T-shirt) undertake a virtuoso display of mixing in duet with the textures of the orchestra. As well as his trademark precision, conductor Vladimir Jurowski brought no little humour to proceedings, adding a repertoire of coughs and yawns between movements that – in a cheeky little dig at concert convention – were ultimately mixed into the ensuing music.

Prokofiev’s textures are often rhythm-led, and while the icy whimsy of the Largo pesante tried to engage with something rather more lyric, it was the big beats of the Adagietto - featuring an elaborate cadenza for Switch (pictured below) and the thumping humour of the closing Allegro gavotte that flourished most authentically in the cavern of the Albert Hall.

Constrained by Prokofiev’s fragmented patterns, the chamber forces of NYO found more release in the music that followed. Britten’s Op 13 Piano Concerto saw them joined by Ben Grosvenor (pictured below left) – a soloist of their own generation, but one whose intellectual maturity exposed the rather more glib elements of Britten’s writing. Dispatching the virtuosic vamping of the opening Toccata with a little too much ease, it was in the bright, nasty grin of the distorted Waltz (and the casual brilliance of his jazz-inflected encore) that he was finally able to bring his musicianship to bear.

Let off the leash after the interval for selections from Romeo and Juliet, Jurowski and the NYO romped and plunged in Prokofiev’s orchestral waters. The surging delight of the eight trombones in The Dance of the Knights was matched for intensity by the solo from the principal oboe, giving way to a Balcony Scene of passionate sincerity. Juliet as a Young Girl gave the players an opportunity to showcase their characterisation skills still further with its quick-change personality shifts, but it was the brutality of their opening – The Prince Gives his Order – that cut right through to the love-death core of the work. Pairing these young musicians with this love story was an inspired piece of programming, and one that brought out not only their energy but also their emotional control.

There’s such a lot of baggage with this violinist, so much effort that goes into being a provocateur, that the music and Kennedy’s own prodigious skill can sometimes get lost in the process. You can’t argue with a musician who can pack out the Royal Albert Hall for a 10pm solo concert of Bach on a Friday night, but you can wish that it were for the right reasons.

There’s such a lot of baggage with this violinist, so much effort that goes into being a provocateur, that the music and Kennedy’s own prodigious skill can sometimes get lost in the process. You can’t argue with a musician who can pack out the Royal Albert Hall for a 10pm solo concert of Bach on a Friday night, but you can wish that it were for the right reasons.

Having trashed contemporary approaches to Bach in his programme note (authentic performance is the bloodless straw man he seeks so conveniently to defeat), the onus was on Kennedy to prove his case. The Preludio from Partita No 3 in E major was his rather tense opening gambit, never quite settling into its pace and smudged with poor intonation. The complete D minor Partita that followed saw him more relaxed, and he found an unexpected grandeur in the cathedral-like space of the mighty Ciaccona, yet for every passage of unaffected musicality there were many more dogged by awkward weighting or technical sloppiness.

Before I get shouted down by those who say I just don’t “get” the Kennedy experience, that in harping on at the technical details I miss the point of this free-spirited musician of the people, I must counter that while phrasing, rhythms and articulation are all fair game in interpreting Bach, intonation is surely an absolute. Here, where a single note must imply an entire chord, it is essential that everything is in its harmonic place or the entire structure wobbles uncomfortably.

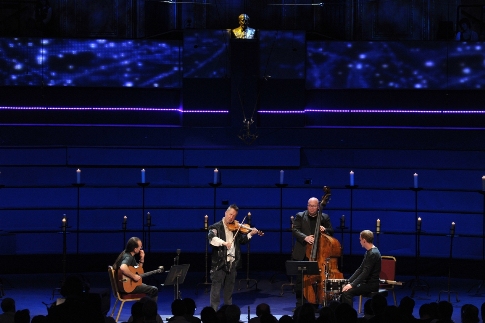

Kennedy’s chief strength is as a communicator - as he proved once joined by his colleagues for a joyously swinging jazz take on Bach (pictured above) - but denied the stimulus and energy of interaction, his performance lacked the communicative urgency and assurance to justify its eccentricities.

Greater even than the standing ovation or the prolonged round of applause in the age of the iPod is surely the journey home from a concert in musical silence – tribute to an evening so filled with aural memories and musical arguments as to keep the earphones in the pocket and ears still in the concert hall while sitting on the District Line. There was enough stimulus here to provide an internal soundtrack for a weekend; they may be the iPod generation but last night Ben Grosvenor, the NYO and Gabriel Prokofiev rendered mine temporarily obsolete, and I can’t thank them enough for it.

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

Appl, Levickis, Wigmore Hall review - fun to the fore in cabaret and show songs

A relaxed evening of light-hearted fare, with the accordion offering unusual colours

Appl, Levickis, Wigmore Hall review - fun to the fore in cabaret and show songs

A relaxed evening of light-hearted fare, with the accordion offering unusual colours

Lammermuir Festival 2025, Part 2 review - from the soaringly sublime to the zoologically ridiculous

Bigger than ever, and the quality remains astonishingly high

Lammermuir Festival 2025, Part 2 review - from the soaringly sublime to the zoologically ridiculous

Bigger than ever, and the quality remains astonishingly high

BBC Proms: Ehnes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson review - aspects of love

Sensuous Ravel, and bittersweet Bernstein, on an amorous evening

BBC Proms: Ehnes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson review - aspects of love

Sensuous Ravel, and bittersweet Bernstein, on an amorous evening

Presteigne Festival 2025 review - new music is centre stage in the Welsh Marches

Music by 30 living composers, with Eleanor Alberga topping the bill

Presteigne Festival 2025 review - new music is centre stage in the Welsh Marches

Music by 30 living composers, with Eleanor Alberga topping the bill

Lammermuir Festival 2025 review - music with soul from the heart of East Lothian

Baroque splendour, and chamber-ensemble drama, amid history-haunted lands

Lammermuir Festival 2025 review - music with soul from the heart of East Lothian

Baroque splendour, and chamber-ensemble drama, amid history-haunted lands

BBC Proms: Steinbacher, RPO, Petrenko / Sternath, BBCSO, Oramo review - double-bill mixed bag

Young pianist shines in Grieg but Bliss’s portentous cantata disappoints

BBC Proms: Steinbacher, RPO, Petrenko / Sternath, BBCSO, Oramo review - double-bill mixed bag

Young pianist shines in Grieg but Bliss’s portentous cantata disappoints

theartsdesk at the Lahti Sibelius Festival - early epics by the Finnish master in context

Finnish heroes meet their Austro-German counterparts in breathtaking interpretations

theartsdesk at the Lahti Sibelius Festival - early epics by the Finnish master in context

Finnish heroes meet their Austro-German counterparts in breathtaking interpretations

Classical CDs: Sleigh rides, pancakes and cigars

Two big boxes, plus new music for brass and a pair of clarinet concertos

Classical CDs: Sleigh rides, pancakes and cigars

Two big boxes, plus new music for brass and a pair of clarinet concertos

Waley-Cohen, Manchester Camerata, Pether, Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester review - premiere of no ordinary violin concerto

Images of maternal care inspired by Hepworth and played in a gallery setting

Waley-Cohen, Manchester Camerata, Pether, Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester review - premiere of no ordinary violin concerto

Images of maternal care inspired by Hepworth and played in a gallery setting

BBC Proms: Barruk, Norwegian Chamber Orchestra, Kuusisto review - vague incantations, precise laments

First-half mix of Sámi songs and string things falters, but Shostakovich scours the soul

BBC Proms: Barruk, Norwegian Chamber Orchestra, Kuusisto review - vague incantations, precise laments

First-half mix of Sámi songs and string things falters, but Shostakovich scours the soul

BBC Proms: Alexander’s Feast, Irish Baroque Orchestra, Whelan review - rapturous Handel fills the space

Pure joy, with a touch of introspection, from a great ensemble and three superb soloists

BBC Proms: Alexander’s Feast, Irish Baroque Orchestra, Whelan review - rapturous Handel fills the space

Pure joy, with a touch of introspection, from a great ensemble and three superb soloists

BBC Proms: Moore, LSO, Bancroft review - the freshness of morning wind and brass

English concert band music...and an outlier

BBC Proms: Moore, LSO, Bancroft review - the freshness of morning wind and brass

English concert band music...and an outlier

Comments

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...