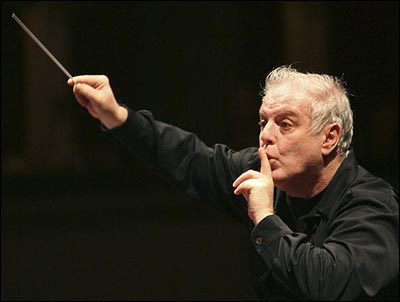

If he isn't careful, Daniel Barenboim is going to find himself on a plinth in Trafalgar Square. He was feted at the Olympic opening ceremony as a great humanitarian, and his West-Eastern Divan Orchestra is being held up as a model for how music can bridge political and ethnic divides, with particular reference to the Middle East. The orchestra's performances of the nine Beethoven symphonies at the Proms have been an event, even if Barenboim's conducting priorities have provoked some critical pursed lips and the hiss of vitriol hitting keyboard.

In this hefty documentary, Michael Waldman followed conductor and orchestra as they brought Beethoven to China and South Korea last year, culminating in a performance of the Ninth Symphony at an outdoor arena virtually in the shadow of the demilitarised zone separating North and South Korea. We were reminded, more than once, that the Ninth and its climactic "Ode to Joy" represent "universal brotherhood", though the rapt expressions on the faces of the Korean audience were far more eloquent about the piece than this nebulous and oft-parroted tag.

This tension between what music does and how it can be described ran through the film. Waldman's narrative was regularly punctuated by members of the W-EDO offering their personal take on the music they were making, so you'd get Israeli viola player Ori talking about the orgasmic tension and release in the Seventh Symphony, or Palestinian violinist Nabih describing Beethoven's vivid use of dynamics in the Sixth Symphony, or Israeli cellist Yael marvelling at the way Beethoven created "cathedral structures" out of tiny musical ideas. Happily, decent-sized chunks of the programme's 90-minute span were devoted to musical performance, so you got a chance to hear theory being put into practice.

This tension between what music does and how it can be described ran through the film. Waldman's narrative was regularly punctuated by members of the W-EDO offering their personal take on the music they were making, so you'd get Israeli viola player Ori talking about the orgasmic tension and release in the Seventh Symphony, or Palestinian violinist Nabih describing Beethoven's vivid use of dynamics in the Sixth Symphony, or Israeli cellist Yael marvelling at the way Beethoven created "cathedral structures" out of tiny musical ideas. Happily, decent-sized chunks of the programme's 90-minute span were devoted to musical performance, so you got a chance to hear theory being put into practice.

However, nobody stood a chance of out-talking Barenboim, not even his son Michael, who's the leader of the orchestra. Even if you take umbrage at Barenboim Senior's chosen tempi, he's one of the world's great theorisers and analysers, always ready to spin out a bit of history, philosophy or metaphorical musicology. Illustrating the mysterious unwillingness of the Fourth Symphony to settle into its home key of B flat, the conductor riffed whimsically about "the search for tonality", and how "you feel you almost need a visa" when Beethoven brushes against the distant key of G flat.

Expanding on a comment by the aforementioned Ori about the way pop music is comforting in its repetitiousness, Barenboim was off about the way we listen (if we can) to the developments and variations within a classical composition. "The human ear is the most intelligent organ that we have!" he insisted. "It remembers vividly." He also went to bat for the perilously chimerical notion of "the universality of music", by which I think he means that the greatest works find a shared emotional or psychological correspondence within anybody who makes the effort to absorb them.

Expanding on a comment by the aforementioned Ori about the way pop music is comforting in its repetitiousness, Barenboim was off about the way we listen (if we can) to the developments and variations within a classical composition. "The human ear is the most intelligent organ that we have!" he insisted. "It remembers vividly." He also went to bat for the perilously chimerical notion of "the universality of music", by which I think he means that the greatest works find a shared emotional or psychological correspondence within anybody who makes the effort to absorb them.

There was a clear and present danger of the film descending into hagiography, a hazard Waldman was doubtless canny enough to have foreseen. It was offset, a bit, by a sequence of Barenboim losing his temper in rehearsals, raging at his young musicians for screwing up the rhythms in Beethoven's Seventh. Waldman tracked him down afterwards and asked if it's only this orchestra who get that treatment. "No, I'm harsh with everybody," roared Barenboim, spluttering with laughter. "'Uncouth' is the word." Then he stumped off in pursuit of musicians to argue with (Barenboim carries the Olympic flag, pictured below, bottom right).

A bit more of the unvarnished maestro would have been welcome, possibly over brandy and cigars in the small hours, but it was still a rare pleasure to watch a documentary which treated music and musicians with sustained seriousness. It was a salutary reminder, too, that the world is sorely lacking in potential new Barenboims, fired by a mission to prove how much music matters.

A bit more of the unvarnished maestro would have been welcome, possibly over brandy and cigars in the small hours, but it was still a rare pleasure to watch a documentary which treated music and musicians with sustained seriousness. It was a salutary reminder, too, that the world is sorely lacking in potential new Barenboims, fired by a mission to prove how much music matters.

Add comment