The White Ribbon | reviews, news & interviews

The White Ribbon

The White Ribbon

Homeland insecurity: Michael Haneke's disquieting pastorale

If you would like to wallow awhile in visions of apocalypse this week, where are you going to turn to: the special effects splurgefest that is Roland Emmerich's 2012 (reviewed here) or the remorseless austerity of Michael Haneke'sThe White Ribbon? Their respective audiences may be almost entirely mutually exclusive.

Palme d'Or hot in hand from this year's Cannes, Haneke is currently the emperor of international art cinema. Only recently, though, he was in the doghouse for his poorly-received American remake of his own 1997 disquisition on violence, Funny Games. For his comeback, the director has chosen to work in his native language for the first time in 12 years, and in that uniquely Germanic genre, the Heimatfilm.

Patriotic, romantic, profoundly sentimental, the "homeland film" as this most untranslatable of concepts is known in English, commemorates a naive pastoral world untouched by modern life. It flowered in the 1950s, as a battered post-war Germany fought to regain its sense of national pride and identity. More recently, directors like Rainer Werner Fassbinder produced ironic revisionist versions of the myth in films such as Katzelmacher. For British viewers, Edgar Reitz's epic, century-spanning Heimat cycle has been, until now, the best-known example.

The White Ribbon is set just before the First World War in a small village in Northern Germany dozing in a quasi-feudal lifestyle under the twin auspices of the landed gentry and the Protestant church. As the story begins, this peace is shattered by a stream of perturbing accidents. First the local doctor breaks his collarbone when his horse is brought crashing down by a tripwire (animal-lovers may baulk at this explicit scene); then a farm worker's wife dies in a fatal fall.

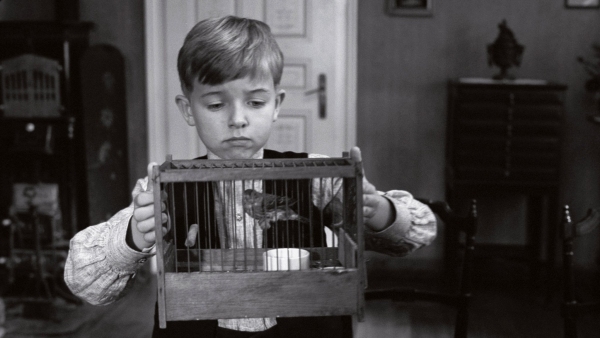

The violence escalates in the course of a year amid the quietly changing seasons. A barn is burned down. Children are beaten, trussed up and tortured. We shouldn't feel too sorry for the doctor, since soon enough he's found cruelly humiliating his mistress and sexually abusing his 14-year-old daughter.  Just for once, Haneke offers minuscule flickers of warmth. The schoolteacher - whose older self narrates the story - launches into the shy, gently comic courtship of a young governess. And there's even something alarmingly close to a Steven Spielberg moment in the scene where an adorable, saucer-eyed little boy offers his father his treasured pet bird when the father's own canary becomes yet another casualty of the malfeasance. But, for the rest, one character who wants out just about sums it up: "Malice, envy, apathy, brutality".

Just for once, Haneke offers minuscule flickers of warmth. The schoolteacher - whose older self narrates the story - launches into the shy, gently comic courtship of a young governess. And there's even something alarmingly close to a Steven Spielberg moment in the scene where an adorable, saucer-eyed little boy offers his father his treasured pet bird when the father's own canary becomes yet another casualty of the malfeasance. But, for the rest, one character who wants out just about sums it up: "Malice, envy, apathy, brutality".

The trailer presents The White Ribbon as a highbrow whodunnit, much in the manner of Haneke's 2005 arthouse hit Hidden. But - while the blustering police officers never nail the culprits - this film makes no secret of who they are: the dead-eyed, thin-lipped, Aryan-blonde children who swarm through the village in gangs and keep popping up at the crime scenes, to ask innocently if they can help out at all.

These children are themselves victims, however, whether it be of corporal punishment, molestation or a simple lack of love. The film wants to show how violence begets violence; and how, as the opening voice-over portentously suggests, these local atrocities "might clarify something that happened later in this country." The white ribbon, a badge of purity which the pastor's children are required to wear, is clearly intended to presage the guilt-stained armband sported by Germans two decades later.

Does this sound, perhaps, a little glib? Well, not for nothing did Haneke win his golden prize in Cannes. His visual style, as seen in the extract above, is icily controlled and highly distinctive. The film is shot in black-and-white, the luminous landscapes offset with cramped interiors dimly lit by oil lamps and haunted by the neurotic spirit of German Expressionism. Staircases abound. And he systematically places his camera - which rarely moves - behind his characters' backs, with bodies or heads dominating the frame (even relatively light-hearted moments like the harvest festival, pictured top, are filmed in this way). It sets up a subtle pattern of disequilibrium, menace, distance. Haneke keeps you at arm's length, constantly blocking you from plunging fully into his world.

I found The White Ribbon disquieting, but not for the intended reasons. For all that the director insists his films are thought-provokingly open-ended, it seemed a little too pat, a bit too insistent - it browbeats us into acquiescence with its jaundiced view of human nature. Does a straight line lead from the child unjustly shamed and beaten to the concentration camp guard? What of all the many factors, economic, historical and cultural, that contributed to the rise of the Third Reich (or any other evil)? Is his twisted Heimatfilm pointing to a fatal flaw deep in the German psyche? Quizzed about all this recently in the New York Times, Haneke had, of course, a ready - and, to my mind, most unsatisfactory - answer. And it didn't stop me from secretly wishing I'd been to see2012 instead.

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](https://theartsdesk.com/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=7tVsLyR-) Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

From Historical to Hip-Hop, Classically Black Music Festival, Kings Place review - a cluster of impressive stars for the future

From quasi-Mozartian elegance to the gritty humour of a kitchen inspection

From Historical to Hip-Hop, Classically Black Music Festival, Kings Place review - a cluster of impressive stars for the future

From quasi-Mozartian elegance to the gritty humour of a kitchen inspection

The Perfect Neighbor, Netflix review - Florida found-footage documentary is a harrowing watch

Sundance winner chronicles a death that should have been prevented

The Perfect Neighbor, Netflix review - Florida found-footage documentary is a harrowing watch

Sundance winner chronicles a death that should have been prevented

Bryony Kimmings, Soho Theatre Walthamstow review - captivating tale of the cycle of life

Witty ode to Mother Nature

Bryony Kimmings, Soho Theatre Walthamstow review - captivating tale of the cycle of life

Witty ode to Mother Nature

Blu-ray: Le Quai des Brumes

Love twinkles in the gloom of Marcel Carné’s fogbound French poetic realist classic

Blu-ray: Le Quai des Brumes

Love twinkles in the gloom of Marcel Carné’s fogbound French poetic realist classic

La bohème, Opera North review - still young at 32

Love and separation, ecstasy and heartbreak, in masterfully updated Puccini

La bohème, Opera North review - still young at 32

Love and separation, ecstasy and heartbreak, in masterfully updated Puccini

Frankenstein review - the Prometheus of the charnel house

Guillermo del Toro is fitfully inspired, but often lost in long-held ambitions

Frankenstein review - the Prometheus of the charnel house

Guillermo del Toro is fitfully inspired, but often lost in long-held ambitions

Shibe, LSO, Adès, Barbican review - gaudy and glorious new music alongside serene Sibelius

Adès’s passion makes persuasive case for the music he loves, both new and old

Shibe, LSO, Adès, Barbican review - gaudy and glorious new music alongside serene Sibelius

Adès’s passion makes persuasive case for the music he loves, both new and old

Solar Eyes, Hare & Hounds, Birmingham review - local lads lay down some new tunes for a home crowd

Psychedelic indie dance music marinated in swirling dry ice

Solar Eyes, Hare & Hounds, Birmingham review - local lads lay down some new tunes for a home crowd

Psychedelic indie dance music marinated in swirling dry ice

The Free Association launch review - strong start for improv company

Troupe moves into permanent home

The Free Association launch review - strong start for improv company

Troupe moves into permanent home

The Lemonheads' 'Love Chant' is a fine return to form

Evan Dando finally gets back in the saddle with an album of new tunes

The Lemonheads' 'Love Chant' is a fine return to form

Evan Dando finally gets back in the saddle with an album of new tunes

Add comment