How To Design The Nutcracker | reviews, news & interviews

How To Design The Nutcracker

How To Design The Nutcracker

Designers Gerald Scarfe, Antony McDonald and John F Macfarlane explain what inspires a Nutcracker setting

Christmas ballet would be unthinkable without The Nutcracker. But what kind of Christmas should it be? This year the UK fields an astonishing array of visions, from Biedermeier formality at the Royal Ballet, to Fanny and Alexander romanticism at Birmingham Royal Ballet, Elvis cartoons at English National Ballet, and expressionist German psychodrama at Scottish Ballet.

Three of Britain's most famous designers, Gerald Scarfe, Antony McDonald and John F Macfarlane, talk here about their preoccupations as they set about picturing the fairytale ballet, and in the gallery elsewhere see a fabulous spread of their sketches and designs.

English National Ballet - Gerald Scarfe

ISMENE BROWN: How did you make the step from political caricature to designing a Nutcracker?

ISMENE BROWN: How did you make the step from political caricature to designing a Nutcracker?

GERALD SCARFE: I’ve done quite a lot of theatrical design, though I’m better known as a political caricaturist with the Sunday Times. But I started way back in the 1960s with the Traverse in Edinburgh. I’ve done about five productions for Peter Hall - one is The Magic Flute which keeps repeating around the world, a musical with him in Chichester, and West End plays. Maybe it’s unusual in that people usually assume my work is cruel and harsh in the political area, but theatre is the other side of the coin. For The Nutcracker I decided to design it for my then five-year-old granddaughter Ella - she’s now 11, and will go again this year with her pals. In a way I did it for her because I felt Nutcracker was the best way to introduce ballet to children and I wanted it to be child-friendly, have jokes in it, visual fun. So I departed very much from what the purists would like to see. My thought was to give it a newer aspect.

Where did you start?

Of course I listened to the music and immediately ideas came into my mind. I made myself a toy theatre, so I can see if the designs work. There is the famous scene where the Christmas tree grows and grows, and that’s quite a technical problem. Mine is a sort of trompe l’oeil - it appears to grow, but it’s more economical. ENB only had a certain budget.

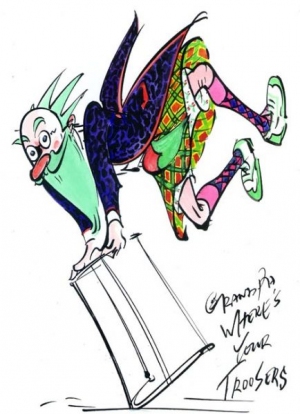

Then there’s always a grandpa - and rather than have the usual doddery old grandpa played by a 23-year-old with a beard on, we’d have a grandpa who is a wily old Scotsman with a busty girlfriend on the side. So I invented this character, Miss V Agra. Then I said to the choreographer I’d like to have him with a zimmer frame, so is it possible for you to develop a zimmer frame dance? So I really set out in many ways to offend fans of the usual type. It meant I could dress people up in outlandish costumes. The little mice are terrorists - they have gasmask-like heads and carry Kalashnikovs. But I was also aware that ballet fans would want to see a proper Sugar Plum Fairy. I let them have at least a few classical treats along the way.

Then there’s always a grandpa - and rather than have the usual doddery old grandpa played by a 23-year-old with a beard on, we’d have a grandpa who is a wily old Scotsman with a busty girlfriend on the side. So I invented this character, Miss V Agra. Then I said to the choreographer I’d like to have him with a zimmer frame, so is it possible for you to develop a zimmer frame dance? So I really set out in many ways to offend fans of the usual type. It meant I could dress people up in outlandish costumes. The little mice are terrorists - they have gasmask-like heads and carry Kalashnikovs. But I was also aware that ballet fans would want to see a proper Sugar Plum Fairy. I let them have at least a few classical treats along the way.

Was it grandpa who triggered the look?

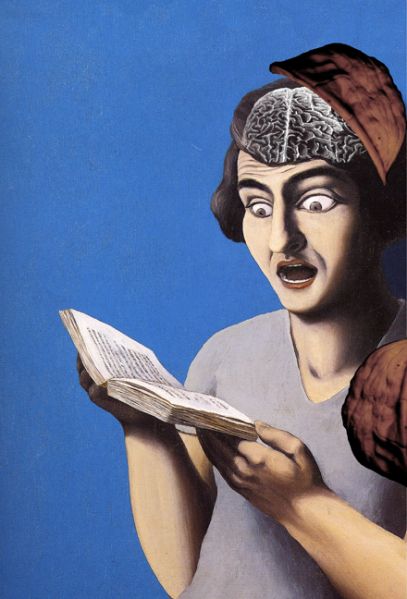

No. I started with the idea that Nutcracker is a book, a story by Hoffmann, and I thought it would be wonderful to have this huge book opened up on stage by the wizard, Drosselemeyer - so he’d open the first page and the winter scene and houses would be an illustration on the page. And from out of the pages, the characters step out and come to life. Then the book opens out again, into an even bigger scene, and on we go.

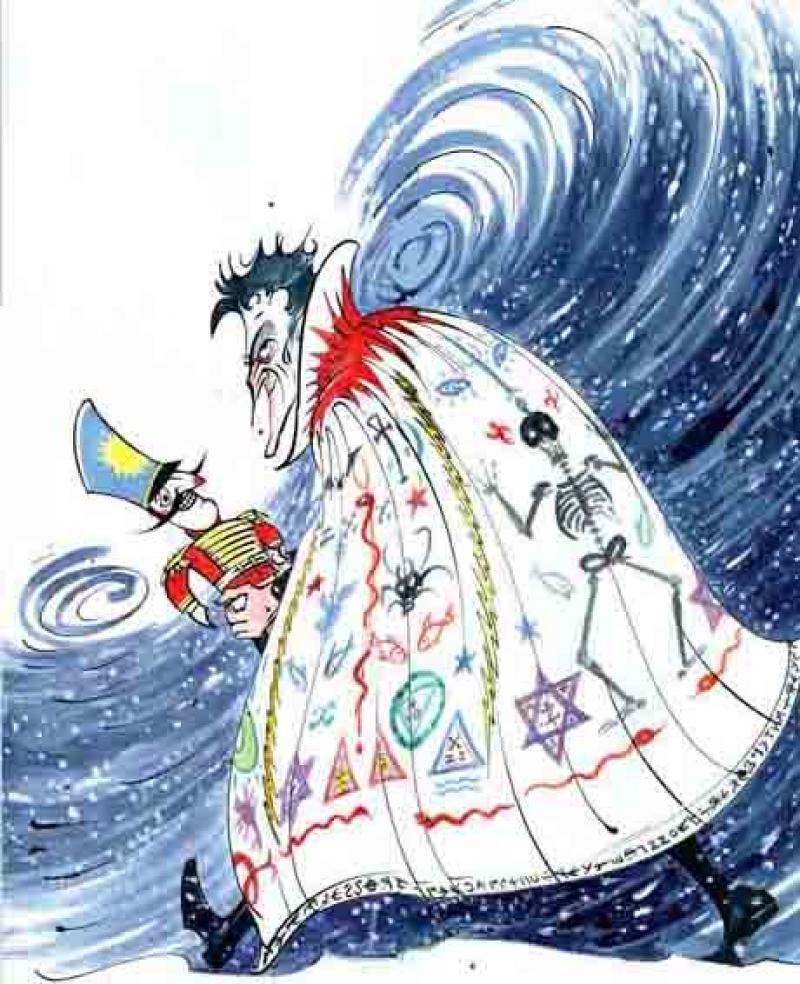

Where did your sketch for Drosselmeyer come from?

My wife’s friend is Nicky Haslam, a society man, and at the time Nicky had this punk haircut, and he’s always been good at reinventing himself. It started with his haircut. Then I went on to little bits of Elvis. I wanted him to look startling, and I wanted him to be able to look magic - so he has a magic cloak with all kind of symbols. I always find it easier to design the villain - they’re the ones the audience loves. So I probably did start with Drosselmeyer, who’s the villain in a way. Probably the last one I did would be Clara. It was quite interesting because suddenly the costume department would ask me what colour knickers Clara was wearing! All these kinds of things one gets asked as a male designer that one hasn’t necessarily thought off. Every single little thing has to be designed and thought of, down to the walking stick and the zimmer frame. Because they’re eccentric, if there’s anything realistic on stage it stands out. I remember when we were running short of money, I decided to dress a couple of the naughty boys in it in T-shirts bought from the high street and they just looked like real T-shirts. I had to paint something onto them to give them “my look”.

Clara is actually the most modern of all, a punky little girl with orange hair.

As I said, it was for my little granddaughter, and I was looking around trying to pick up the main strands of it. And because her normal hair didn’t look right, I bought her a red wig. I love working with colour - painting a whole stage with colour. And when all the casts are assembled on stage it’s a riot of colour. Almost like a box of Smarties.

What about the fridge with the Snowflakes jumping out?

What about the fridge with the Snowflakes jumping out?

That was my idea. Of course, being a cartoonist and in my other job, I’m sort of trying to think of funny ideas, but also startling ideas. I suppose it started by thinking, what’s very cold? Well, either North Pole or a fridge - I thought of an upmarket fridge with lobsters and champagne in it.

Did you separate the “real” from the “fantasy” worlds?

It’s all fantasy really, but it’s good for the public to have a few nods to society we live in. It’s useful to make references to the world we all know, if one can. Especially as it kind of has a pantomime echo and as you know in panto they often have contemporary comments about what’s on TV.

Like the terrorist Mice - they’re the attackers, they are undermining that world. Five or six years ago we were worrying a lot about terrorism. At one time, I had them living in a cake, then we built the cake - and the cake moved about the stage rather like a tank. There was a little mouse general at the top directing the steering of the cake. But I designed it for the Coliseum, which is a very big stage, and of course travelling to other stages it didn’t fit in, and the cake got dropped. It was another thing to carry around. So I’m afraid the Mice lost out.

Did you direct and shape the story?

Matz [Skoog, artistic director of ENB at the time] came to me and said he wanted it to be visually led, design-led, and he couldn’t decide whether to give me a young up-and-coming choreographer like Christopher [Hampson] or an experienced older one. Luckily he gave me Christopher who was very amenable to my ideas. So I actually insisted it should be called “concept and design by Gerald Scarfe” - I wanted it to be known as mine and I didn’t want anybody else to get the blame for it, because it was quite bizarre. I knew Matz wanted me to come in from the outside world with fresh air. If anything it’s gained audiences as it’s gone along. There was initially a sort of gasp when it came on because of what I’d done to darling Tchaikovsky, I remember two ladies in Southampton sitting near me who were absolutely appalled, and ballet critics were not particularly kind to it. It was as if I’d raped The Nutcracker.

- English National Ballet's Nutcracker is at the London Coliseum 16 December-3 January. Book online here

Scottish Ballet - Antony McDonald

Was this your first Nutcracker?

Was this your first Nutcracker?

Yes, I’d never done a big classical ballet up till then. I’d done one-acters of contemporary type with Ashley [Page, Scottish Ballet artistic director], like Ebony Concerto at the Royal Opera House. In fact it was the first time for both of us to look at one of those narrative 19th-century chestnuts. We collaborated from the start on exactly what kind of libretto we wanted and the format we wanted. I remembered the music, from the Royal Opera House one. I wanted to try to not do it like that. The Tchaikovsky version was very much filtered through a French Alexandre Dumas version of the original Hoffmann story, and I think that softened it quite a bit. So we went back to the Hoffmann original - we wanted to investigate some of the darker story. I love those Hoffmann stories, I think they’re highly underrated. Wagner was very influenced by Hoffmann too... It’s much more about what’s happening to this young girl, Marie, very much about someone being awakened. Clara is her doll, I think. The whole Drosselmeyer element is spooky, dark. Drosselmeyer did magical things when visiting the children - he did unnatural things like apparently twisting limbs, creating illusions. He was not necessarily a benign character.

How do you find a parallel today?

What about Harry Potter? Vampires? Weirdly I think today there is an undercurrent that life isn’t always only what we see. There is a real interest in people not being quite what they seem. Is Drosselmeyer an alien? Well, he’s supernatural. The other thing we investigated from the original story is the Mouserink character, who is a kind of another evil character. There’s a whole backstory there, left out of the original Tchaikovsky ballet libretto, which we sort of did as an entertainment for the children, but in which the parents were also involved.

What age do you see Marie/Clara as?

What age do you see Marie/Clara as?

In our production she does mature from being a young girl. In the original story there’s quite a lot of reference to smashing glass and blood, I think it’s when she’s putting the dolls into a glass-fronted cupboard, and this is broken. There’s quite a lot of blood imagery. Definitely in the Hoffmann the underlying theme is that this is someone who’s arrived at puberty, that there is now a sexual-romantic dimension to life. She’s growing from having a relationship with toys to one with a flesh-and-blood man.

How did you develop the look?

We wanted it to feel German, as it was originally a German story. So it would be Weimar, that period after the First World War in which Germany did flourish for a while. We wanted it to have a Max Beckmann quality. I knew that period, and loved his work. The whole thing is a dolls house that we based on a Beckmann house - like a copy of the big house. I don’t know if you know that play Tiny Alice by Edward Albee. It is a copy of the house they’re in. A bit surreal.

What were the key moments for you?

The growth of the tree and the battle. I suppose we wanted to do it in a new way that hadn’t been seen before, so our Christmas tree was in an pot which became enormous and could be defended like a fort, and the tree was almost out of sight. I’m not sure we got those things as right as we could have done.

How did you decide on the Nutcracker costume?

How did you decide on the Nutcracker costume?

Before he becomes the nephew, he has a half-mask which makes him look quite hideous, like he had a big mouth to put the nut. That was quite important, because it showed Marie that she could love something hideous. Which I think is a big lesson to learn, that you shouldn’t judge people by what they look like.

Your favourite costumes?

I loved the mice being women! They have little jackets and pleated skirts and umbrellas. We tried to make them look quite frightening as opposed to sweet. The Snowflakes had those icy blue tutus - and there were two bad Snowflakes, for whom I was much inspired by paintings of Dorothea Tanning, and they are slightly naughty Victorian children. They were two contemporary barefoot dancers in the company, in little shredded icy-blue grey dresses with long hair standing on end (picture below).

What about Harry Potter? Weirdly I think today there is an undercurrent that life isn’t always only what we see

The diverts are all extensions of characters you’d already seen - like the mother does the oriental divert in a sort of Turkish outfit, which was sort of based on imagining the dress you’d seen earlier had been recut with harem pants. And the grandfather does the Chinese. It’s all as if Marie imagined her family doing these dances. Marie herself becomes the Sugar Plum Fairy. The Waltz of the Flowers had Poppies, Courgette Flowers... I loved doing those costumes. It was my first venture into doing tutus of any sort. I was lucky to work with a great costume-maker in Germany, Angela Sproll, who’s done all the tutus of the three big ballets we’ve done.

They have a lot of fabric - what are the constructions?

You don’t want them to look like every other tutu you’ve ever seen. That’s the challenge. You learn by doing, I guess. To begin with I was resistant to things that looked hard or stiff, and with the Waltz of the Flowers the Poppies were quite big, romantic tutus, whereas when I got to Marie’s final tutu it was quite short and stiffer. There is amazing scope within the tutu to do these things, but you need a wonderful maker. It’s the top layers that you put your mark on. There are all these things you have to obey, about not overdecorating the waist because of the partnering - if they’ve got to be lifted, you’d got to be able to have a securet grip at the waist, it can’t have diamante and shred someone’s hands.

You don’t want them to look like every other tutu you’ve ever seen. That’s the challenge. You learn by doing, I guess. To begin with I was resistant to things that looked hard or stiff, and with the Waltz of the Flowers the Poppies were quite big, romantic tutus, whereas when I got to Marie’s final tutu it was quite short and stiffer. There is amazing scope within the tutu to do these things, but you need a wonderful maker. It’s the top layers that you put your mark on. There are all these things you have to obey, about not overdecorating the waist because of the partnering - if they’ve got to be lifted, you’d got to be able to have a securet grip at the waist, it can’t have diamante and shred someone’s hands.

Every night they get soaked with sweat and make-up - how durable are they?

Not incredibly! I think in Russia a lot of those bodices were made for about two or three performances, and thrown away. They’re all dry-cleanable but after a tour they all have to have a lot of rehab. That’s the thing - if you try to push the boat out and do something original there’s a knock-on effect.

Was this production designed to be tourable from the start?

Yes. You can see, set-wise, it’s easy to tour. You’re guided by the technical director of Scottish Ballet, Tim, who knows all the theatres we visit, and he’ll tell you when you suggest something, that isn’t going to work in Aberdeen or something. You never quite know what may happen to a piece after a tour, it might be invited to a different country. Pennies From Heaven, we knew, couldn’t have any flying in it because it had to go to the Queen Elizabeth Hall in London at one point, although it also went to masses of places in Scotland where it could have had flying.

What would you like to leave as the overall impression of your Nutcracker?

Interesting question... I would like them to find it magical, obviously, but also unexpected. Obviously for someone who’s never seen it before, magical. For people who’ve seen lots of Nutcrackers, you hope it would take them by surprise and feel original, rather than handed down.

- Scottish Ballet's Nutcracker is at Glasgow's Theatre Royal 12-31 December; Edinburgh, Festival Theatre, 6-9 January 2010; Inverness, Eden Court 20-23 January; Aberdeen, His Majesty's Theatre 27-30 January; Newcastle, Theatre Royal 3–6 February. Booking details here

Birmingham Royal Ballet - John F Macfarlane

JOHN MACFARLANE: It was actually the one of the three Tchaikovskys that I least wanted to do. I always wanted to do Swan Lake, and would still like to. But this one I’d never thought was for me, and I said I’d think about it. The only thing I really wanted was that Clara didn’t watch all the dances. Usually they sit like statues or dummies watching, and I always feel that kills Act 2. I said to Peter this was a condition, almost, to rework Act 2, because it didn’t work here in London. I also massively wanted to change the scale of the Christmas tree so that it was far more dynamic than just getting a bit wider and a bit taller.

JOHN MACFARLANE: It was actually the one of the three Tchaikovskys that I least wanted to do. I always wanted to do Swan Lake, and would still like to. But this one I’d never thought was for me, and I said I’d think about it. The only thing I really wanted was that Clara didn’t watch all the dances. Usually they sit like statues or dummies watching, and I always feel that kills Act 2. I said to Peter this was a condition, almost, to rework Act 2, because it didn’t work here in London. I also massively wanted to change the scale of the Christmas tree so that it was far more dynamic than just getting a bit wider and a bit taller.

How did you decide what look to go for?

I don’t really like that Biedemeier satin dropped shoulders period that Peter had in London for the Royal Ballet. I had just seen Bergman's Fanny and Alexander, which starts with a Christmas party and all these wee kids running about, snatching things off the Xmas tree. And I felt I liked that late Victorian period, almost Edwardian, and the austerity of formal clothes of that period. Black, and red, wonderful hot red rooms.

I presume the most important single costume is the Sugar Plum Fairy, because she’s the focus of all the dreams of all the little girls.

Oh... I don’t really know. The girls' ones are quite boring. The ones I least enjoy are the formal tutus, because you’re so hidebound by tradition. When you get into the diverts it’s much better because you can be very inventive, and be sculptural too. But you can’t do that with Sugar Plum or Aurora or Cinderella - they just have to look stupendous, edibly beautiful. I think the only concern I had with Sugar Plum Fairy was the colour pink, which I don’t like much as a colour, but we found this lovely greyed pink and put a lot of beadwork on it to tone the colour down

All these big ballets have pivot points in the score, which is when you should really travel, travel, travel. You can’t shortchange them with the staging

Which female costumes did you enjoy making most?

I love the adult women, especially the mother’s dress. And I enjoyed doing Clara’s friends.

All that soft, blonde muslin

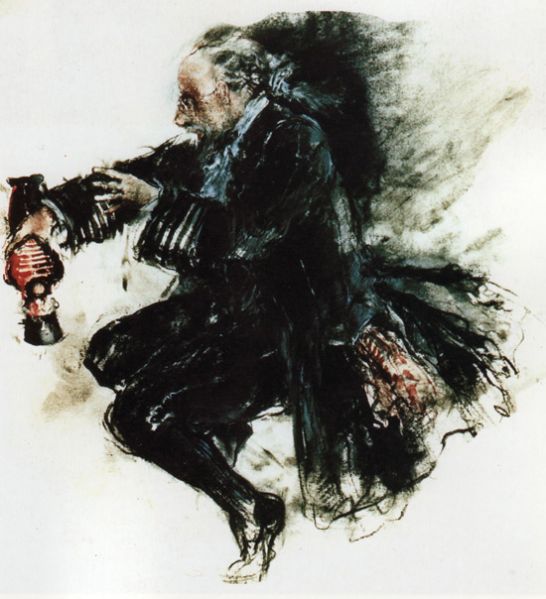

Yes, and when they run down the stairs, the cloth softly settled around them. But my favourites are really the rats, the Rat King especially. The most important thing is not to be pretty. I think it’s that thing of finding real evil, something that you are afraid of, to balance all the beautiful stuff. In Nutcracker that whole scene at night, when she comes down, completely changes into a very alien space - and especially when the tree starts to grow it should be a very scary, shivery moment. This entire room is travelling, turning. And if the rats come on looking pretty, you’re lost. The entire sense of terror is broken.

So I was thinking of them being a Napoleonic Army in retreat. They have quite Napoleonic costumes, all shredded, filthy, and I spend a lont long time with Robert Allsop, with whom I worked on the clay model of the rats’ heads, to get the nose line very long and very mean. They’re starved, they’re starved rats.

So I was thinking of them being a Napoleonic Army in retreat. They have quite Napoleonic costumes, all shredded, filthy, and I spend a lont long time with Robert Allsop, with whom I worked on the clay model of the rats’ heads, to get the nose line very long and very mean. They’re starved, they’re starved rats.

But ultimately you must have spent most imagination on conceiving the startling transformation of the room when the Christmas tree grows - that’s the bit everybody remembers and that has become pretty much legendary in this Birmingham production. It just is phenomenal.

Yes, I did that first. I think all these big ballets have pivot points, around which the whole evening turns. You know that’s the thing that’s going to change. In Sleeping Beauty it’s three different ones, the entrance of Carabosse which needs to be terrifying, really terrifying, not mimsy or funny - and when the palace is put to sleep, and then the awakening. Which is when you should really travel, travel, travel.

In Cinderella, which I'm doing now with Birmingham Royal Ballet, it’s the striking of midnight. In these ballets, those are the moments of the score when everybody in the orchestra is employed, and you can’t shortchange them with the staging. With this one I’d never done anything like this before, and there was a period when everybody said to call it off. Fortunately Peter had just said it was “for Birmingham”, so I thought as long as it worked there in the Hippodrome that was all the mattered.

How does the transformation work?

There are three main frames, then you’ve got your normal Christmas tree, and it grows upwards, and you don’t see the moment when it picks up the lower half and gets off the ground - there are two travelling big pieces of tree that come in from the side, and as they do, the back frame lifts and allows the perspective wall to turn around into the big image. You’ve got a lot of people on the ground as well turning the fireplace, and there’s another truck at the back that’s pushed on with the dancers on it. Nobody sees the soldiers come on. There’s a huge number of people behind, on the fly floor and on the ground pushing all these things. You’re also taking all the lighting booms that have been in the room that have to fly out and then fly back in. It’s a huge, huge change. It pretty nearly killed us getting it on stage, and we never saw it until the general rehearsal! I’d never seen it once.

I remember at that rehearsal the great moment of getting the massive tree out and the big fireplace back, and transiting into the Snowflakes. That point, I don’t think anybody knew how to do - because we’d been so focused on the massive part. And somehow it did actually work! It took me about a year and a half to be able to watch the changes. When they opened the new Birmingham Hippodrome there was a low wall around the back of the stalls, and if I was in for a performance, once I saw the butler starting to blow out the candles I’d go, “Oh, here we go,” and duck down behind the wall, and I couldn’t watch. Because if any of these first pieces weren’t taken out right, and the huge pieces start to turn, you’d smash the entire thing.

That fireplace is magnificent - it makes me feel really hot. I absolutely adore this transformation. Do you ever compare notes with other designers about Nutcracker?

Never. I know quite a few who’ve done this ballet, but we never talk about it.

Is it because it’s so personal? You are musical?

Yes, I play the piano. The whole dynamic is playing that transformation music endlessly and understanding it. Actually in Act 2 as well, very often, there’s a great importance in not letting people feel let down. You should arrive in the Kingdom of Sweets and initially feel it’s a bit disappointing and dismal - she arrives there and it’s a bit empty and grey. And then Drosselmeyer comes on and brings it to life.

You said you wanted to do this in a different way - was it intended as a slightly internal journey for an adolescent Clara?

You said you wanted to do this in a different way - was it intended as a slightly internal journey for an adolescent Clara?

I think that was Peter’s take.

Drosselmeyer is often old - and your original drawings are, aren’t they? But when it was played by handsome Joe Cipolla, it became instantly right that this Drosselmeyer was young and became a desirable figure in Clara’s fantasy.

I hadn’t thought of that, but you’re right. It’s much closer to that.

It’s also much more painterly. Did you ask yourself what’s in a girl’s bedroom?

No [laughs]. I’m a painter first and foremost, so I supposed I just wanted this wonderful opportunity to paint, throwing things into the room - ribbons, flowers, the emblems from Act 1.

But all slightly more impressionistic, more grown-up - and slightly more suggestive.

I think all the way through what I dreaded was that it would be in any way “pretty” - I don’t mean not beautiful, goodlooking, exciting. But it is so easy for that act to tip into over-prettiness, and you don’t need to do that for kids. When you go to these performances, these little girls have all dressed up in sparkly stuff and dance shoes, and they’re totally ready for that stage. So if you don’t give them that identification with themselves, you’d let them down... they have to want to be that, but it doesn’t have to be pretty-pretty. I mean, Miyako Yoshida [BRB's leading ballerina at the time] is probably the ultimate Sugar Plum Fairy for me, she ruined it for everybody else, because she was so special.

What about those male costumes? What about the male Winds in the Snowflakes waltz?

My most hated costumes. There’s always an afterthought with men’s costumes. The choreographer starts by saying, I don’t need any men in the Snowflakes - then realises that at the end of the big crescendo you’ll want the girls to be lifted. The same in the Valse des Fleurs, it turned out they did need cavaliers after all. Those were much easier. But I hate all-overs and body stockings, and I doubly hated having “bits” attached, which the Winds had. They’ve now had three redesigns. The first was absolutely appalling, and I couldn’t look at them, I was excruciatingly embarrassed. They looked like painted bodystockings with bits streaming off. Ballet-ballet costumes. So then I remade them, building them on 18th-century court costumes, completely shredding them, and the headdress was based on 18th-century hair. So they’re OK now.

My most hated costumes. There’s always an afterthought with men’s costumes. The choreographer starts by saying, I don’t need any men in the Snowflakes - then realises that at the end of the big crescendo you’ll want the girls to be lifted. The same in the Valse des Fleurs, it turned out they did need cavaliers after all. Those were much easier. But I hate all-overs and body stockings, and I doubly hated having “bits” attached, which the Winds had. They’ve now had three redesigns. The first was absolutely appalling, and I couldn’t look at them, I was excruciatingly embarrassed. They looked like painted bodystockings with bits streaming off. Ballet-ballet costumes. So then I remade them, building them on 18th-century court costumes, completely shredding them, and the headdress was based on 18th-century hair. So they’re OK now.

You can’t do that with the prince.

It’s always the same problem with him. He’s a greyer version of the Sugar Plum Fairy’s pink. I found the best thing was to look at military uniform - you know, these wonderful ceremonial evening military uniforms, if you keep in that world, you’re giving them a neat, trim and beautiful jacket.

How do you get away from stereotypes or iconic images?

You simply design the “character”. I don’t think I ever have any iconic figures in mind. There are very big variations on the prince’s costumes, you vary them a lot for each dancer. You absolutely have to make sure each dancer is happy in it. There’s no point in my saying this jacket WILL go down and cover your bum, because some dancers hate that and want a really short neat one. Others like it longer. You remake the jacket for each one as they want it. For Albrecht I think there are around 22 different variations, short and long. It’s about being comfortable.

Is it the most expensive ballet production?

No, I don’t think so. The thing that I constantly remember is that a ballet production is not just what you’re seeing on stage - it’s not one Sugar Plum Fairy and one Prince, but four of each, or seven or nine Clara’s-friends costumes, not just the four you see. That’s all built into your first budget. You get quite shocked as you see how many costumes you’ve got to come out with.

- Birmingham Royal Ballet's Nutcracker is at the Birmingham Hippodrome 27 November-13 December. Nutcracker booking line. Check out Birmingham Royal Ballet's season listings

Now see theartsdesk's full gallery of design sketches from all three Nutcrackers

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Dance

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Like Water for Chocolate, Royal Ballet review - splendid dancing and sets, but there's too much plot

Christopher Wheeldon's version looks great but is too muddling to connect with fully

Like Water for Chocolate, Royal Ballet review - splendid dancing and sets, but there's too much plot

Christopher Wheeldon's version looks great but is too muddling to connect with fully

iD-Reloaded, Cirque Éloize, Marlowe Theatre, Canterbury review - attitude, energy and invention

A riotous blend of urban dance music, hip hop and contemporary circus

iD-Reloaded, Cirque Éloize, Marlowe Theatre, Canterbury review - attitude, energy and invention

A riotous blend of urban dance music, hip hop and contemporary circus

How to be a Dancer in 72,000 Easy Lessons, Teaċ Daṁsa review - a riveting account of a life in dance

Michael Keegan-Dolan's unique hybrid of physical theatre and comic monologue

How to be a Dancer in 72,000 Easy Lessons, Teaċ Daṁsa review - a riveting account of a life in dance

Michael Keegan-Dolan's unique hybrid of physical theatre and comic monologue

A Single Man, Linbury Theatre review - an anatomy of melancholy, with breaks in the clouds

Ed Watson and Jonathan Goddard are extraordinary in Jonathan Watkins' dance theatre adaptation of Isherwood's novel

A Single Man, Linbury Theatre review - an anatomy of melancholy, with breaks in the clouds

Ed Watson and Jonathan Goddard are extraordinary in Jonathan Watkins' dance theatre adaptation of Isherwood's novel

Peaky Blinders: The Redemption of Thomas Shelby, Rambert, Sadler's Wells review - exciting dancing, if you can see it

Six TV series reduced to 100 minutes' dance time doesn't quite compute

Peaky Blinders: The Redemption of Thomas Shelby, Rambert, Sadler's Wells review - exciting dancing, if you can see it

Six TV series reduced to 100 minutes' dance time doesn't quite compute

Giselle, National Ballet of Japan review - return of a classic, refreshed and impeccably danced

First visit by Miyako Yoshida's company leaves you wanting more

Giselle, National Ballet of Japan review - return of a classic, refreshed and impeccably danced

First visit by Miyako Yoshida's company leaves you wanting more

Quadrophenia, Sadler's Wells review - missed opportunity to give new stage life to a Who classic

The brilliant cast need a tighter score and a stronger narrative

Quadrophenia, Sadler's Wells review - missed opportunity to give new stage life to a Who classic

The brilliant cast need a tighter score and a stronger narrative

The Midnight Bell, Sadler's Wells review - a first reprise for one of Matthew Bourne's most compelling shows to date

The after-hours lives of the sad and lonely are drawn with compassion, originality and skill

The Midnight Bell, Sadler's Wells review - a first reprise for one of Matthew Bourne's most compelling shows to date

The after-hours lives of the sad and lonely are drawn with compassion, originality and skill

Ballet to Broadway: Wheeldon Works, Royal Ballet review - the impressive range and reach of Christopher Wheeldon's craft

The title says it: as dancemaker, as creative magnet, the man clearly works his socks off

Ballet to Broadway: Wheeldon Works, Royal Ballet review - the impressive range and reach of Christopher Wheeldon's craft

The title says it: as dancemaker, as creative magnet, the man clearly works his socks off

The Forsythe Programme, English National Ballet review - brains, beauty and bravura

Once again the veteran choreographer and maverick William Forsythe raises ENB's game

The Forsythe Programme, English National Ballet review - brains, beauty and bravura

Once again the veteran choreographer and maverick William Forsythe raises ENB's game

Sad Book, Hackney Empire review - What we feel, what we show, and the many ways we deal with sadness

A book about navigating grief feeds into unusual and compelling dance theatre

Sad Book, Hackney Empire review - What we feel, what we show, and the many ways we deal with sadness

A book about navigating grief feeds into unusual and compelling dance theatre

Add comment