theartsdesk Q&A: Comedian Rowan Atkinson | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk Q&A: Comedian Rowan Atkinson

theartsdesk Q&A: Comedian Rowan Atkinson

The face of Blackadder and Bean on a life spent entertaining, and taking on a tragicomedy

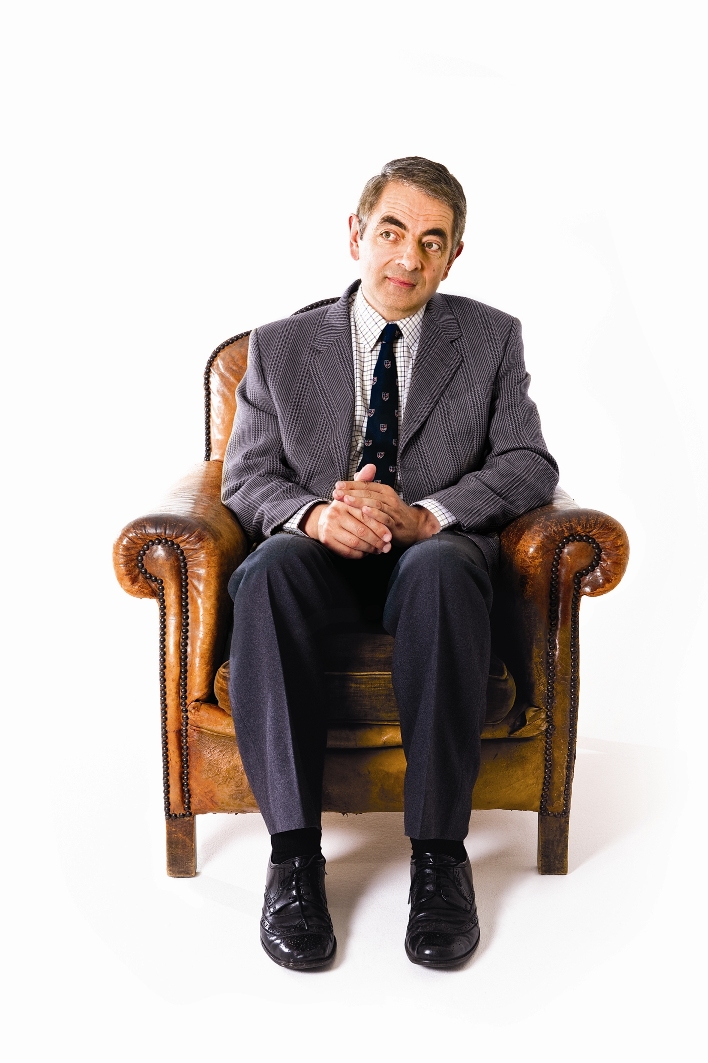

The generation of alternative comedians who emerged around 30 years ago have long since elbowed their predecessors into the long grass and themselves become the establishment. Of no performer can that be said with more certainty than Rowan Atkinson. His rubbery physiognomy is instantly recognisable to billions, which is why he – or rather Mr Bean - was granted pride of place at the Opening Ceremony as guest artist with Sir Simon Rattle and the London Symphony Orchestra.

His curriculum vitae barely needs restating. He is the only performer from Not the Nine O’Clock News who still makes a living by making audiences laugh. From there he became the star – the master of ceremonies, he calls it – in another longer-running ensemble piece. Blackadder walked into a hail of German bullets on the night Mrs Thatcher lost the leadership of the Conservative Party, since when Atkinson has been driving more or less solo as Mr Bean, whose move to the big screen produced the most successful British film of all time. Two Bond-spoofing instalments of Johnny English followed.

Films really are so long-term and stressful and difficult, so I just thought I fancy something smaller

But it was as on stage that it all started for Atkinson, as a child at school, then at Oxford and on to Edinburgh revues. He soon had his own name in lights on Shaftsbury Avenue – with his loyal feed Richard Curtis cueing up the gags. That was as far back as 1981, the same year and the same street that a new play by Simon Gray was premiered called Quartermaine’s Terms. Atkinson happened to see that play and he happens now to be starring in it. Although he starred as Fagin in Oliver! in 2008, this is the first time he will be acting (as opposed to singing) on stage since the late Eighties when he was in a play called The Nerd (“in which I played, unsurprisingly, the title role”). And it is the first time ever that he’ll be attempting to embody a character - St John Quartermaine, a dreamy, hapless teacher at a language school in Cambridge - who is at least as tragic as he is comic.

He doesn’t need to do it. His triumphs have stuffed Atkinson’s garage with sports cars and rendered further work unnecessary. He tells theartsdesk what is driving him, starting on this page with the Opening Ceremony of the Olympics, then about performing onstage (page 2), becoming a comedian (page 3), television (page 4) and Bean (page 5).

THE OPENING CEREMONY

JASPER REES: It would be a dereliction of duty not to start with your most recent appearance with the LSO running along the beach at St Andrews. Only I’m not quite sure what to ask.

JASPER REES: It would be a dereliction of duty not to start with your most recent appearance with the LSO running along the beach at St Andrews. Only I’m not quite sure what to ask.

ROWAN ATKINSON: I could give you an answer almost without a question.

How long ago were you asked about that?

March, I think. So relatively recently, and it came through Richard, yet again, Richard Curtis. The Chariots of Fire was his idea and then we developed it together in the rehearsal room, just trying things out. It’s that difficult thing, to provide Olympic comedy. You know, comedy for the Olympic Games is quite tricky, because of the very nature of the event, and obviously perforce it can’t be verbal, so that excludes, you know, most comedians, and you tend to end up with people like me who have done quite a lot of visual comedy over the years. So we knew it had to be a visual comedy piece. So Danny Boyle asked Richard to ask me if I would like to do it and I was happy to consider it but the key is coming up with the idea that’s going to work. And having decided that it was going to be visual comedy then the next most logical was to make it a musical joke, because music is a good lubricant for visual comedy, because otherwise it can become a little static and a little tense. We’ve done quite a few musical jokes over the years and this was just another one.

I was nervous but no more nervous than I normally am, which is fairly nervous but not too nervous

Simon Rattle I met and grew to like a lot in the few days that we were together. And he was a very important part of it because the whole point of it was to sell a dummy, that this was going to be a very serious and actually slightly dull idea, that the London Symphony Orchestra would now play a tribute to the British film industry. Here we go, a medley of slightly well-worn tunes. But he was an essential part of setting up an idea that we could then pull the rug from under. It had to be, I am afraid, pre-recorded in order for it to work on the night. And Danny is just the sweetest brightest guy. An awful lot of the success of the Opening Ceremony was obviously to his credit, but I think it was more than just his skill as the director, it was his integrity as a human being. At two of the dress rehearsals we had 30,000 people in the stadium, and because he gave this speech beforehand saying “Save the surprise, don't tell anyone what you see tonight, keep your mobile phones in your pockets,” his integrity was something that people bought into and they didn’t want to abuse the request which meant that so little of what we did was known about in advance.

You were appearing in front of 80,000 in the stadium, God knows how many live around the world. Were you nervous?

I was nervous but no more nervous than I normally am, which is fairly nervous but not too nervous. I mean the odd thing about stadia, if that’s the plural, and of course the television audience is you can’t see the whites of their eyes. They’re an amorphous mass out there of noise and you’re aware of their presence but I think it’s far more nerve-racking to stand in front of 45 people at a wedding reception in your local church hall than it is to perform at the Olympics Opening Ceremony, literally because you can see the whites of their eyes, and you can see the expression of people that you know and half know, and that I feel is far more pressure. And of course notionally the idea of a global television audience which obviously was a major part of it – that is the Mr Bean audience. The nature of Mr Bean is he had been as well known in Shanghai as he is in Venezuela as he is in Wolverhampton and he’s been in that state for 20 years. So the notion of a worldwide audience is familiar to me.

That’s not in any sense to take away from the specialness of that particular night, but in the end what you concentrate on is just getting it right by rehearsing it. If you tell the story, which is the only job an actor has, of this guy who has got the most boring music task in the work, which is to play a C sharp repeatedly for four minutes and 10 seconds, then what’s his story? And that’s how we rehearsed it. What’s interesting is that I couldn't play the C sharp. I had to play the D. The C sharp’s a black note that you can’t keep an umbrella tip on while playing repeatedly. Very very difficult. We discovered that fairly early on. I am surprised that no one’s written in and said, “You’re a semitone sharp.”

PERFORMING ONSTAGE

Talking of the whites of their eyes, you don’t have to do theatre. What made you want to?

Having done Fagin in Oliver!, that I didn't hate doing as much as I thought I was going to, I knew it was a part that I wanted to play, but generally speaking when I play a part I find it hard work and quite stressful and then comes regret, certainly if you’re stuck in a show for seven months like I was with Oliver!, you start to question the wisdom of what you are doing, when actually with Oliver! I didn't because it was a great show to be part of, and I reminded myself, I suppose, not having done a show like it for 20 years, that actually I’m quite comfortable onstage. I feel I know how stage works and I think I know how to do it. And when thinking about what I was going to do next after Johnny English Reborn (pictured below right), I thought films really are so long-term and stressful and difficult, so I just thought I fancy something smaller.

I suppose also there's a bit about advancing years, about ageing. Something I’ve always been determined to do, to a great or lesser extent - you don't always do it – is to try to act your age. To try to not pretend you’re 26 still and do things that are of your time and of your age and your hopefully received wisdom. So Quartermaine fitted that extremely well. Even though it is a supposedly starring role, it’s more a pivotal role. It’s not actually a particularly large role. I’m there. I’m omnipresent. I remembered Edward Fox doing it and I thought, I think I could do that, I think I understand what Simon Gray was trying to create with that part. In many ways it’s odd because it’s a character without any character. He’s a sort of blank canvas. Very curious. Those in the staff room use him as this receptacle into which they can pour out their concerns. Where’s he from? Has he been married? Does he have feelings for any of the other characters? Even by the end you're not quite sure what he’s about. You sort of come to sympathise. It’s a quite curious character. But you could say the same about Mr Bean. What’s he on about? Where’s he from? And of course to a certain extent you could say he’s in a slightly similar vein in terms of their performance.

Are you in general a theatre goer?

Are you in general a theatre goer?

No, not half as much as I should be. I’m not a cinema goer. I’m terrible for not doing enough of that stuff. Whenever I’m sitting in meetings where we’re writing these films and people start talking about “Have seen Inception?” I think, nnnno. And then they reel off two other films that any normal cinema goer who’d consider themselves an enthusiast and has the pretensions to be a filmmaker himself should have seen, and I haven’t seen any of them. I rely very much on received wisdom when it comes to plays and films.

Is it a fear of being disappointed? You’ve made a number of the most successful British films of all time.

Yes. Odd really. Certainly I should know more about British film. The funny thing is because of the nature of media and because everything is talked about so much and trailed so much, you feel as though you’ve seen films you’ve never seen and feel as though you’ve got a pretty strong opinion about films you’ve never seen. Partly received wisdom from friends, partly because you saw a trailer on the internet or on the cinema or on the relatively rare occasions when you’re there. So you think, oh I know what that’s going to be like.

Is it also that you have to sit in a cinema with other people?

Um, no I wish I could claim that that was the problem but that’s not the problem, because actually cinemas are pretty private places. So no, well I’m sorry. I probably shouldn’t be admitting this ignorance. I think I know what’s going on. When I’m at home I’m a terrible view of television. I can always think of something that I would rather be doing. That’s the truth of the matter.

What would they tend to be?

Reading a car magazine probably. Yeah, just reading and socialising. You know. It’s quite a commitment, isn’t it, to go and sit in a black hole for two hours.

You’ve asked a lot of people to do it for you.

You’ve asked a lot of people to do it for you.

I know, so I should damn well get off my bottom and go and do it.

That’s enough of the Jesuitical self-flaying. When did you first know that you could perform in front of audiences?

Very young. I seem to remember doing school stuff when I was at primary school, so six, seven. I remember doing strange Christmas shows. The old woman who lived in the shoe. And I must have felt something then. It became quite focused when I was about 12 when I played the Dauphin in George Bernard Shaw’s St Joan. Quite a serious piece for a prep school.

I’ll say.

I think the red pen went through it. It wasn’t as long as it might be. I’d heard Kenneth Williams played it. It’s supposedly or traditionally quite a camp and ineffectual figure. I can remember nothing about it except it seemed to work. These are all stepping stones when you acquire confidence in your ability to do these things.

As you went on to Oxford, was it in any way a kind of drug?

I don’t think so. I can’t say that I’m addicted to it because I’m so cautious about it and once I’ve done it I’ve had enough of it very quickly.

I mean the hearing people laughing and therefore approving.

Well obvously you must... you must like it, you must grow to like it and to a certain extent grow to enjoy it. I always have a pretty ambiguous attitude towards it simply because, you know, it’s nice to be liked but I’m rarely, only very rarely, elated by it. I think that’s the best way of describing it. Normally when I get to the end of a film or to the end of a show and it’s worked and the box office is good and people have enjoyed it, all I feel is.. is relief. Thank God that we didn’t fail. But I can probably count on the fingers of one hand the number of times when performance has made me feel elation. Generally it’s a tremendous concern that at any moment it could go very very wrong.

Could you list a couple?

It’s half amazing and half frightening because you’re not in control any more

I seem to remember once in that first show in the West End. I seem to remember in the middle of what would later be termed a Mr Bean sketch, even though we hadn’t christened him Mr Bean at the time - because we did Mr Bean-like sketches on the stage for 10 years before he ever appeared on screen – and it’s strange when you feel a joke running away with itself in a pleasing way. You’ve used your creativity and energy or what have you to bring the comic moment to a certain level and then suddenly you find that it’s actually rolling away down the hill far from you which is both elating but also rather frightening because it’s no longer within your grasp. It’s leapt out of your grasp and it’s become something bigger or more successful than you ever thought possible. As you know I’m a bit of a car person, and Ayrton Senna about whom there was a very good documentary made last year, was practising for a Monaco Grand Prix - I suppose it must have been in the mid or late Eighties - driving for McLaren, and he was with his team mate Alain Prost and they were first and second on the grid but in qualifying Alain Prost set a fantastic lead fast time and then Ayrton Senna beat it by half a second, which is quite a lot. Then suddenly he was a second faster, and suddenly he was over a second faster, and he was going round and round and round and round and round and round, and he described it as a slightly out-of-body experience where he felt he was being propelled by forces beyond his control and he had to force himself to stop because otherwise he would have just crashed, but somehow he felt as though it was no longer in his gift. He being a religious person slightly thought it was the hand of God. He had a strong spiritual side to him which I don't have which he would probably credit with whatever happened to him. But in many ways onstage and in jokes, you can experience that where you bring it this far and that’s as far as you want it to go actually. It needn’t be any better received than that. And then suddenly the combination of a live audience and their belief in it and then you give a bit more that you never thought you were going to give and then the whole thing starts to build into quite a tumult. But that’s only happened five times or less. But it’s half amazing and half frightening because you’re not in control any more. It’s something else. Circumstance is driving it. Sorry if that all sounds a bit pretentious and improbable.

(Pictured above, Atkinson in rehearsal with Quartermaine's Terms director Richard Eyre)?

(Pictured above, Atkinson in rehearsal with Quartermaine's Terms director Richard Eyre)?

BECOMING A COMEDIAN

Back to your childhood. How much do you feel like you hail from the North-East?

To be honest, very little. The North-East is a fantastic part of the world and the people are fantastic but I don’t think I ever felt quite comfortable there if I have to be honest. One of the problems of just being a privately educated middle-class boy in the North-East in the 1960s when the culture of the region was extremely industrial, very working-class, very Newcastle Broon and Newcastle United – that was the world – unsurprisingly it was a world in which I had little identity in terms of my personal experience. So there was always a bit of me that was looking outwards and that means probably southwards. I went to university in Newcastle and had a good time. So I think there was always a hankering. Whatever I wanted to do I felt I was more likely to be able to do in the south than in the north. I think that’s the essence of it and I think that is true. And when I went to Oxford in 1975 after doing my first degree at Newcastle I felt that I was in a better place. That sounds terrible, as if the south is better than the north, but it was a place which suited me better.

Did you have a plan?

No I didn't have a plan and the reason why I didn’t try to get a job after I’d got my first degree, it was partly because I was very young – I went to university when I was 17 so I graduated when I was only 20 and I thought this is too young and in any case I should explore better the potential for acting, and I thought if I’m going to do that maybe I should do a research degree and the most logical place to go in terms of the people, the Pythons and the Beyond the Fringe people who had preceded me, would seem to be Oxford or Cambridge.

So it was a very conscious move to go to Oxford not to study electrical engineering. It was to study acting.

I would say it was half “I don’t want a job yet” and half “if I’m not going to get a job and I’m going to do a research degree, wouldn’t it be nice to it somewhere where the drama and performance would be better explored?”

Did you put much into your research degree?

Not as much as I should have done because I was there to do a DPhil, as they call a PhD at Oxford, and I didn’t do a DPhil, I ended up just with a Masters, with an MSc, which is quite a rare degree at Oxford. I did my thesis on self-tuning control systems and it was good enough for an MSc but not good enough for a DPhil. So yeah, I was distracted sufficiently not to be able to realise my academic ambitions as much as I should have done. But I was determined to get a degree. I was determined not to leave with nothing, which I could easily have done.

When you did leave,was your mind very made up that you’d done the right thing and your course was set?

Um, the decision to pursue a performance career was made after the first year which was when Richard and I first did a revue together, which was called After Eights because the Eights are the rowing race in Oxford. I think it was a pun. And I knew then that, OK, I should give this a go. So the next two years was just spent, Richard and I doing more shows, going to Edinburgh, going to the Edinburgh Fringe quite a bit which we started to do. We first went there in ’76, I think, and then ’77, ’78 and 1980. So I went to Edinburgh a tremendous amount at the end of the Seventies. And then we started doing a radio show and of course it was ’79 that Not the Nine O’Clock News started.

Why back then did you need to pursue this? What was luring you down this path? And the second part of the question is why do you need to do it now? You could sit at home and read car magazines, to use your phrase. You don’t need to do it.

It’s easier to answer the second question. The reason I like to carry on doing it now is because it’s something you feel you can do. We all seek to do a job. I think to do nothing and stare at the wallpaper... I mean, I thoroughly enjoy reading car magazines and I can read them till the cows come home but in the end you can’t do it for more than, say, five hours a day. In the end you need to do something else. We’re all seeking a degree of job satisfaction and I feel as though I can get it by continuing to perform. And therefore I must get something out of it. There’s no point in saying, “Oh it’s a miserable and stressful and ghastly experience,” which a lot of the time it is actually because I do wind myself up hugely, but if you choose the right people to work with... That was the thing that Oliver! taught me or presented me with - the idea of merely being a cog, even if a slightly large cog, in a big machine. Whereas generally speaking the things that I’ve done, the revues, the stage, shows, the films where you are really the entire raison d’être of the project, you are the machine. What I learnt was that Oliver! was going to happen anyway with or without me. There was this wonderful feeling of divesting responsibility for script, production, direction, other actors, to other people in the form of Rupert Goold and Cameron Mackintosh, people who know what they’re doing, so you can say, “I don’t have to worry about that. All I have to do is sing these songs, do these dances, play this part and go home.” I love that idea of shared responsibility between a lot of actors, which is sort of what we had in The Blackadder actually, even though The Blackadder was the title role yet again. With Stephen and Hugh and Tony Robinson there was a feeling very often of merely being a master of ceremonies, which I was pleased to be. “Ladies and gentlemen, Mr Stephen Fry will now come on and be amusing for a minute and half. And now my friend playing Baldrick will come on and be very funny also.” So there was this very nice sense of shared responsibility which I don’t have with Mr Bean. Mr Bean is a very singular and far more stressful experience.

I’ve already asked you earlier about the hit you might get out of making people laugh.

And I gave a cautiously positive response to that: yes there is but... I mean clearly I must have derived some satisfaction from it. I mean some of my friends think, and they may not be wrong, that actually what was driving me a lot was the feeling that with the earnings, that actually the money was a big factor, that actually if I wanted to buy an Aston Martin, this was probably the best way of achieving that end.

And you did want to buy an Aston Martin.

And I did want to buy an Aston Martin and sure enough the first car I bought of any great value in 1981 was an Aston Martin V8. So I wonder whether there was a terrible practical and mercenary side of me that I’d discovered a skill that has a commercial future, if you like. Maybe if I’d discovered performance but knew that I was condemned to being in a small company of absurdist theatre actors touring round the Highlands and Islands of Scotland for the rest of my life – ie earning no money but performing – then maybe I wouldn't have done it. But there is no point in saying it was a purely commercial thing. I personally don't believe it, although I can believe it was a factor. But there must have been something about it that I liked. It’s that thing about being drawn to something which you know is difficult but you feel the need to do it.

TELEVISION

When did you last watch a Not the Nine O’Clock News sketch?

I don’t know. A few years ago maybe. And sort of by accident. Because of the nature of modern media there’s usually something that you’ve done somewhere on most days because of the number of channels and the number of repeats. I think it was Gerald the Gorilla which I remember enjoying (see video below).

Do they stand up?

Yeah some of them do. Not the Nine O’Clock News was very topical. But I’m pleased actually with the longevity which seems to be attached to quite a lot of what I’ve done. The Blackadder in particular, because sitcoms normally after 10 years start to show their age and I think The Blackadder’s got remarkable legs. Of course it benefitted hugely from the fact that we didn’t set it in the time that we made it. That’s always the problem with sitcoms - when you can see the 1980s sofas and curtains and hairstyles, that distances you slightly from the comedy. Bean I think is a pretty timeless age joke.

Do you always say “The” Blackadder? Everyone else knows it as Blackadder?

I don't know where the definite article comes from. I think I do call it The Blackadder. Or sometimes The Adder when amongst close friends and intimates. I don’t know why I do. Maybe because the first series was called The Black Adder and I’ve stuck with that.

We hear about rock bands who reunite without actually liking one another.

The Eagles?

I’m not saying there are animosities among your former colleagues...

Well none on that scale, I can tell you that, no.

But have you ever talked about doing another Not the Nine O’Clock News reunion?

Not the Nine O’Clock News, good gracious. I thought you were going to say Blackadder. Not the Nine O’Clock News has certainly not been spoken about. I mean occasionally I do feel, wouldn’t it be great to have a programme like it on TV at the present time? You just need certain topical issues to come to the fore and you just think, surely there are fantastic ironies and absurdities to be pointed up here which I am sure that a good producer and some good writers and good performers could do. Occasionally people do; people like Rory Bremner are hacking away at the coalface when they can. But it’s not easy. The way we did it, Not the Nine O’Clock News would be considered very expensive now for a topical comedy show. I think the problem in the end, particularly with The Blackadder, is advancing years. When things are successful like Not the Nine O’Clock News or The Blackadder, what they represent to me is a happy consensus that existed between a number of creative people, normally four or half a dozen, at a particular time in their lives. And you cannot assume that by getting those same people together 10 years later, 20 years later, that the same consensus could exist, because we all change as we age and we all do different things and people get used to, for example, being in control and not compromising their position, whereas when you’re 24 working on a top-class sketch show and someone writes a sketch set in a chemist shop and you say, “Right, who’s going to play the chemist, who’s doing to play the customer?” you don't care. You’ll play the chemist if you feel like playing the chemist or you’ll play the customer. Whereas if you asked those same people 20 years later, “Do you want to play the customer or the chemist?” they’ll say, “Well, what should I be doing at this point in my career? Should I be playing the chemist or the customer? Is this right for me? How does this fit in with my career plan?” You just think about things far more and too far in many ways later in life.

Could it be as simple as “I don't want to play the feed”?

It could be that, because you feel as if your status is now different and you don't want to compromise in the way you used to. This is not just with performers. It’s with writers. Writers come up with sketches and the producer goes, “That’s a load of rubbish, write another one,” and when they’re 29 they go away and write another one and when they’re 39 they say, “No, that’s my sketch, take it or leave it.” And things change with time. And therefore, particularly with The Blackadder... If we could all act our age... I’ve always thought the new Blackadder would be in the Second World War in a prisoner-of-war camp, which is a nice combination of hierarchy and claustrophobia, which I think are the two factors that help the Blackadder conceit very much. But no one in a prisoner-of-war camp was older than 28. So in what sense could we, well into middle age, represent that time and place? So you’ve got to think of a different idea, if one was ever going to pursue it, which I think is highly unlikely. There is no animosity that I’m aware of between all the different creative elements, the writers, actors and producers. But there is a, you know... I’m not sure there’d be the same working relationship that we had 25 years ago, which is hardly surprising really.

Would you describe yourself as a fairly collaborative person or have you got less collaborative over the years? Do you trust the judgement of others? Do you collaborate as well as you did 25 years ago?

I think I do actually, but then I’d be the first to admit that I’m someone who likes to be in control, but I think that was the same 25 years ago as it is now, so I don’t think I’ve changed very much. Something I’ve always been very cautious about is trying only to do the jobs that I’m good at which is why I’ve never wanted to direct anything that I’ve done, for example; I’ve never wanted to write things that I do. The way I put it with all the films I’ve done, the Mr Bean movies and the Johnny English movies, I’m very much part of the writing process, I contribute to the writing process and I come up with ideas, but in terms of sitting down and making it work in script form I’m very very keen and happy to leave it to other people. And the same with direction. I probably have more opinions about direction so I do need to work with directors who are willing to listen to my view. But the important thing to me is I’ve never wanted to do the job for myself and certainly never wanted to claim credit for the job myself, whereas with others I feel they feel the need to have that degree of control. I’ve never felt that need. Particularly film has to be a collaborative process but I’ve always felt the need to have the last word, in the end to be in control to that extent. But I just don't want to do all the jobs, that’s all.

It’s been a long time since I saw The Tall Guy.

It’s been a long time since I saw The Tall Guy.

In it you play an extremely controlling stand-up comedian. Were you sending yourself up?

I’m probably not the person to ask. Richard is probably the person to ask, because he wrote it based, I suppose undoubtedly, on his experiences of us working together. Yeah, I suppose there was a degree of self-parody. I like to think obviously it was a gross exaggeration. But maybe it wasn’t. It would be foolish certainly for me to claim that it’s nothing to do with me, the whole story. But yeah, to a certain extent it was very funny. The bottles of champagne this size [Atkinson holds his finger and thumb about three inches apart]. I’m afraid I’m very happy to make jokes about things I’ve done or versions of things I’ve done. That’s fine by me.

BEAN

Is Mr Bean due for a resurrection?

I don’t know. Yet again, act your age. I’m just slightly self-conscious about him being a rather ageless, timeless figure. He’s always been fairly ill-defined and of course when I look at some old Mr Bean sketches now I look incredibly young. And that’s fine. When you get older you’ve just got to accept it and there’s no reason why Mr Bean can’t get older I suppose. Because I’ve always seen him as a cartoon-like figure who doesn’t really age, I feel rather self-conscious. When we did Mr Bean’s Holiday - quite recently, wasn’t it? 2007 – and I thought then, I was very happy to do it and I was physically very capable of doing whatever was... visual comedy can be physically quite demanding on your body – but I felt as though I don't know if I really want to carry on doing things like this because it’s quite demanding.

I was wondering whether you were going to say demeaning.

Yeah well I think that is a factor. There’s no doubt, with age you start to lose a certain comic authority, I think, to perform in certain ways and do certain jokes, because in the end Mr Bean and to a much lesser extent Johnny English - it’s quite childish humour, it’s quite child-like. I mean the essence of Mr Bean is that he is a child trapped in a man’s body and that’s what’s funny about it - his selfishness and his instinctive anarchy are funny to watch. But yeah, to a certain extent you think maybe I’m just growing out of this. Maybe it’s sensible to acknowledge that it’s been fun and to draw a line under it.

Final question, to do with your wonderfully comic face which you’ve used to brilliant effect all these years. What do you see when you look in the mirror? What is your relationship with this comic instrument?

I don’t know. I don't see it as a comic instrument when I’m looking in the mirror. Because I have spent 99.9 per cent of the time not pulling faces, it is the most familiar mode from my perspective. And I certainly don't stand in front of mirrors pulling faces. Well I don't see any character that I’ve played, let’s say that much. That’s the odd thing. We all have a very specific and singular relationship with our own face which can be quite different to how other people see it. I just see the face that I’ve seen since I was born, getting slightly older but otherwise... I don’t see or feel when I look at my face any aspect of my professional life. That’s something else.

You must know what you are capable of doing with your face, though.

Yes I am. Although the last time that I sort of checked it was probably in 1976 when I had to do a purely visual short comic sketch for a review in Oxford, and I’d never performed at Oxford before and I’m not much of a writer so I couldn't be bothered to write anything, and Richard and I hadn’t started working together at that point and I did literally just stand in front of a mirror and start to pull faces of an extreme nature. They seemed to me to be very funny and I developed a sort of a gobbledygook speech, so the combination of a gobbledygook speech and silly face-pulling turned into something called the Message Mime where I came onstage and tried to give a message to remember for the audience and then got very angry when they didn’t take it. It was a slightly complicated conceit. That was really the start of face-pulling for me. But since then I suppose I’ve just hoped that whatever I think my face is doing, it is doing. I’ve never felt the need to check it or practise it. It just expresses what I feel the performance needs to tell the story. Has that answered the question? I can’t think of anything else to say.

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Add comment