'The Rolling Stones of Morocco' - Nass El Ghiwane's music of protest | reviews, news & interviews

'The Rolling Stones of Morocco' - Nass El Ghiwane's music of protest

'The Rolling Stones of Morocco' - Nass El Ghiwane's music of protest

At this year's Gnawa Festival in Essaouira on Morocco's Atlantic coast, a tribute to a revered member of a legendary band

Fly into Morocco on Royal Air Maroc, and as in-flight entertainment on the overhead screens you’re treated to Charlie Chaplin shorts from the 1910s, still sharp as a tack, the little guy goosing authority, the law, the rich, the powerful. The Little Tramp must remain a figure with resonance in Morocco: the base of operations for legendary band Nass El Ghiwane was the back room of a tailor’s shop in Casablanca dominated by a poster of Chaplin.

Their songs were about the same "little guys" that Chaplin’s comedy immortalises, the struggle of poor Moroccans and the search for poetry in a new urban reality. They have been one of the most famous bands in Morocco for more than three decades, and the spirit of Nass El Ghiwane was celebrated this year at the 16th Gnawa Festival in Essaouria (pictured below).

This four days of music was bookended by two spectacular Gnawa fusions between Mahmoud Guinea, Essaouira’s great ghimbri-wielding Malaam, and Cuba’s Omar Sosa; and Will Calhoun’s superb young American quartet on the closing night with Mustapha Bekbou. These are fusions of tradition and modernism for which the festival is famous, and in Morocco, the origin of that fusion tradition is Nass El Ghiwane.

This four days of music was bookended by two spectacular Gnawa fusions between Mahmoud Guinea, Essaouira’s great ghimbri-wielding Malaam, and Cuba’s Omar Sosa; and Will Calhoun’s superb young American quartet on the closing night with Mustapha Bekbou. These are fusions of tradition and modernism for which the festival is famous, and in Morocco, the origin of that fusion tradition is Nass El Ghiwane.

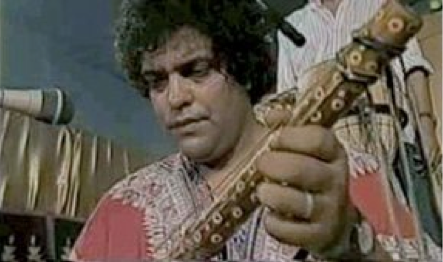

They’ve been dubbed "The Rolling Stones of Morocco" – there isn’t much resemblance, though these were long-haired young men who smoke and drank and put bottles of wine or beer and a few joints between the stage lighting in front of them so they could drink and play during the gig. They released their first album 30 years ago, and with the recent death of Abderrahmane "Paco" Kirouche, the Essaouira native who brought the heavy bass sound of the ghimbri of the Gnawa to Nass’s modernist sound palette, the Festival’s Tribute to Paco was led by his son and featured a line-up of banjo, ghimbri, frame drum, kit drum and tam tam augmented by a trio of Gnawa and what resembled the huge, deep-bass trumpet used by Tibetan monks (Paco Kirouche, pictured below left).

As the saying goes, this is strong shit, at times matching the total immersion of cross-rhythms and inexorable propulsion of 1970s Miles Davis at its most dense. They played the port stage, the super-moon rising behind them, the sun setting over the Atlantic and Portuguese escarpments ahead, and to an audience of around 150,000. The ghimbri and banjo wind in between each other under impassioned vocals, the whole mass of it stepping up to a free-floating sweet spot on the forward momentum of massed percussion, including the Gnawi, and what a web they weave, doubling up the rhythm and doubling it again like some musical demonstration of the golden mean.

The Nass story begins in the 1960s, in the decade following Moroccan independence. They got together in the melting pot of Al-Hay al-Muhammadi, a sprawling working class neighbourhood in Casablanca, all of them having come from far-flung corners of the kingdom with their families in search of work, and as such were a fusion of rural and folkloric traditions, forged in the furies of modern urban industry.

The Nass story begins in the 1960s, in the decade following Moroccan independence. They got together in the melting pot of Al-Hay al-Muhammadi, a sprawling working class neighbourhood in Casablanca, all of them having come from far-flung corners of the kingdom with their families in search of work, and as such were a fusion of rural and folkloric traditions, forged in the furies of modern urban industry.

Ucef Adel, the London-based, Rabat-born DJ and musician behind acclaimed fusion album Halalwood, knows the surviving band members, has been a regular fixture at the Gnawa Festival for years. His own music is very much a progression of the modernist fusion that Nass created and inspired. “Omar Syyed was Berber,” he says of the band’s roots. “La’arbi Batma was Arab, from Casablanca. The banjo player Allal Yalla, he’s from the south of Morocco.” Paco was from Essaouira. “And there was Boujmii, from the desert area of Morocco, and he had the best voice of Nass Il Giwane.”

Their first songs were for the Theatre Municipal in Casablanca, a kind of post-independence Moroccan National Theatre. “Their songs were from the plays they were involved with,” says Ucef. “They became famous on TV, then they took those songs onto the stage.” With them they mixed some halqa, a magic gum of theatre, poetry, stories, music and dance that may still be experienced at night in the Jmal el Fnar in Marrakech. And they used folk instruments – sentir, frame drums, ghimbri, tambourines – but in a modernist way, fusing elements that hadn’t existed before. Despite the struggle they went through, they had a lot of success, a lot of influence, not only in Morocco, but Algeria, Egypt, the Middle East.

“They wrote about the poor Moroccan guy,” says Ucef, “the struggling guy, and you have all these elements, the making of it, the fabric. Their cultures, where they come from, and all their styles came with them to compose the songs we know. They’re based on fusion elements. They were one of the first bands to have two singers, then three – Omar, Bakta, and Boujmir. They work it out so well to fit with the music, it’s almost unnoticeable. And it was all modern. Totally modern, urban.

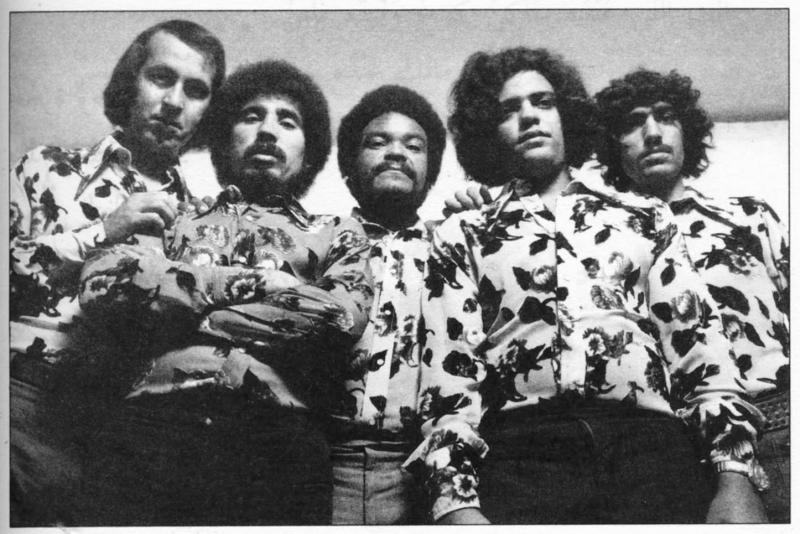

"It was an urban music, an urban style. From working class Casablanca. And despite the struggle they went through, they had a lot of success, a lot of influence, not only in Morocco, but Algeria, Egypt, the Middle East. People like Khaled listened to them. Their concerts had to be stopped because people went crazy and the authorities didn’t have the proper training and enough force to control them. The minute they saw people jumping and dancing, they just freaked out and closed it down” (the early days of Nass El Ghiwane, pictured below).

Nass always denied they were a political group. Their famous song, Essiniya (Tea Tray), has a man addressing the contents of his tea tray in a Casablanca café, from which a stirring social commentary rises up from the song like steam from a glass. They used poetry and allusion to infuse dissent, not direct protest. One song that did cause trouble was Malmouni, with its chorus of "my greatest concern is for the men when they disappear". This was during the "Years of Lead", when dissidents and activists could find themselves in jail or worse. When called to police headquarters in Casablanca to explain, Omar Syedd told them the lyrics were about Palestine. That was permissible.

Nass always denied they were a political group. Their famous song, Essiniya (Tea Tray), has a man addressing the contents of his tea tray in a Casablanca café, from which a stirring social commentary rises up from the song like steam from a glass. They used poetry and allusion to infuse dissent, not direct protest. One song that did cause trouble was Malmouni, with its chorus of "my greatest concern is for the men when they disappear". This was during the "Years of Lead", when dissidents and activists could find themselves in jail or worse. When called to police headquarters in Casablanca to explain, Omar Syedd told them the lyrics were about Palestine. That was permissible.

In 2009, two years before Paco’s passing, I saw Nass rouse the crowd again when they performed on the Gnawa Festival’s Beach Stage – usually the platform for young Moroccan bands, MCs and hip hop artists. Today, those artists still follow the Nass template of fusing new and old forms with lyrics that address the lives of ordinary people.

“Today, bands like Hoba Hoba Spirit are a protest band, and a lot of Moroccan rappers speak that way,” says Ucef. “There’s a band called Hausa that have that kind of lyrical background. Gnawa lyrics are very significant, too.” You can see that in the fervour of involvement anywhere among the huge Moroccan crowds that come to see the likes of Bekbou and Guinea take off. “They all have meanings… It’s all there,” says Ucef. “It’s all connected, it’s all fusion. It’s about coming together.”

Watch footage of Paco from Nass El Ghiwane performing in Essaouira, from the film Transe

.

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more New music

'Deadbeat': Tame Impala's downbeat rave-inspired latest

Fifth album from Australian project grooves but falls flat

'Deadbeat': Tame Impala's downbeat rave-inspired latest

Fifth album from Australian project grooves but falls flat

Heartbreak and soaring beauty on Chrissie Hynde & Pals' Duets Special

The great Pretender at her most romantic and on the form of her life

Heartbreak and soaring beauty on Chrissie Hynde & Pals' Duets Special

The great Pretender at her most romantic and on the form of her life

The Last Dinner Party's 'From the Pyre' is as enjoyable as it is over-the-top

Musically sophisticated five-piece ramp up the excesses but remain contagiously pop

The Last Dinner Party's 'From the Pyre' is as enjoyable as it is over-the-top

Musically sophisticated five-piece ramp up the excesses but remain contagiously pop

Moroccan Gnawa comes to Manhattan with 'Saha Gnawa'

Trance and tradition meet Afrofuturism in Manhattan

Moroccan Gnawa comes to Manhattan with 'Saha Gnawa'

Trance and tradition meet Afrofuturism in Manhattan

Soulwax’s 'All Systems Are Lying' lays down some tasty yet gritty electro-pop

Belgian dancefloor veterans return to the fray with a dark, pop-orientated sound

Soulwax’s 'All Systems Are Lying' lays down some tasty yet gritty electro-pop

Belgian dancefloor veterans return to the fray with a dark, pop-orientated sound

Music Reissues Weekly: Marc and the Mambas - Three Black Nights Of Little Black Bites

When Marc Almond took time out from Soft Cell

Music Reissues Weekly: Marc and the Mambas - Three Black Nights Of Little Black Bites

When Marc Almond took time out from Soft Cell

Album: Mobb Deep - Infinite

A solid tribute to a legendary history

Album: Mobb Deep - Infinite

A solid tribute to a legendary history

Album: Boz Scaggs - Detour

Smooth and soulful standards from an old pro

Album: Boz Scaggs - Detour

Smooth and soulful standards from an old pro

Emily A. Sprague realises a Japanese dream on 'Cloud Time'

A set of live improvisations that drift in and out of real beauty

Emily A. Sprague realises a Japanese dream on 'Cloud Time'

A set of live improvisations that drift in and out of real beauty

Trio Da Kali, Milton Court review - Mali masters make the ancient new

Three supreme musicians from Bamako in transcendent mood

Trio Da Kali, Milton Court review - Mali masters make the ancient new

Three supreme musicians from Bamako in transcendent mood

Hollie Cook's 'Shy Girl' isn't heavyweight but has a summery reggae lilt

Tropical-tinted downtempo pop that's likeable if uneventful

Hollie Cook's 'Shy Girl' isn't heavyweight but has a summery reggae lilt

Tropical-tinted downtempo pop that's likeable if uneventful

Add comment